- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Maureen O'Donnell is a psychiatric patient, stuck in an affair with Douglas, a shady therapist. She’s about to end it with him when she wakes up one morning to find him in her living room with his throat slit. Viewed by the police as both a suspect and a witness, even Maureen’s family suspects her. Panic-stricken, she retraces Douglas' last days, finding a trail of rape and deception at a psychiatric hospital where she’d been an inmate. The patients won't talk and staff are afraid. Then a second brutalised corpse is discovered and Maureen realises that her life is in danger.

Release date: September 20, 2007

Publisher: Back Bay Books

Print pages: 450

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

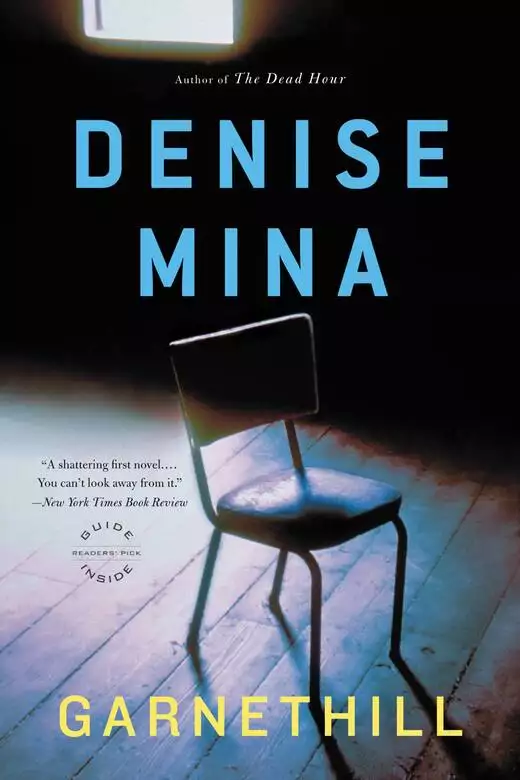

Garnethill

Denise Mina

MAUREEN

MAUREEN DRIED HER EYES IMPATIENTLY, LIT A CIGARETTE, WALKED over to the bedroom window, and threw open the heavy red curtains. Her flat was at the top of Garnethill, the highest hill in Glasgow, and the craggy North Side lay before her, polka-dotted with cloud shadows. In the street below, art students were winding their way up to their morning classes.

When she first met Douglas she knew that this would be a big one. His voice was soft and when he spoke her name she felt that God was calling or something. She fell in love despite Elsbeth, despite his lies, despite her friends’ disapproval. She remembered a time when she would watch him sleep, his eyes fluttering behind the lids, and she found the sight so beautiful that it winded her. But on Monday night she woke up and looked at him and knew it was over. Eight long months of emotional turmoil had passed as suddenly as a fart.

At work she told Liz.

“Oh, I know, I know,” said Liz, back-combing her blond hair with her fingers. “Before I met Garry I used to go dancing . . .”

Liz was crap to talk to. It didn’t matter what the subject was, she always brought it back round to her and Garry. Garry was a sex god, everyone fancied him, said Liz, she had been lucky to get him. Maureen was sure that Garry was the source of this information. He came by the ticket booth sometimes, hanging in the window, flirting at Maureen when Liz wasn’t looking.

Liz began a rambling story about liking Garry and then not liking him and then liking him again. Two sentences into it Maureen realized she had heard the story before. Her head began to ache. “Liz,” she said, “would you do me a favor and get the phones today? He’s supposed to phone and I don’t want to talk to him.”

“Sure,” said Liz. “No bother.”

At half-ten Liz opened her eyes wide. “Sorry,” she said theatrically into the phone, “she’s not here. No, she won’t be in then either. Try tomorrow.” She hung up abruptly and looked at Maureen. “Pips went.”

“Pips? Was he calling from a phone box?”

“Aye.”

Maureen looked at her watch. “That’s strange,” she said. “He should be at work.”

Half an hour later Liz answered the phone again. “No,” she said flatly, “I told you she’s not in. Try tomorrow.” She put the phone down. “Well,” she said, clearly impressed, “he’s eager.”

“Was he calling from a phone box again?”

“Sounded like it. I could hear people talking in the background like before.”

The ticket booth was at the front of the Apollo Theatre, set into a triangular dip in the neoclassical façade so that customers didn’t have to stand in the rain while they bought their tickets. It was a dull gray day outside the window, the first bitter day of autumn, coming just as warm afternoons had begun to feel like a birthright. The cold wind brushed under the window, eddying in the change tray. The second post brought a letter stamped with an Edinburgh postmark and addressed to Maureen. She folded it in half and slipped it into her pocket, pulled the blind down at her window and told Liz she was going to the loo.

Douglas said he was living with Elsbeth but Maureen felt sure they were married: twelve years together seemed like a lifetime and he lied about everything else. Three months ago the elections for the European Parliament had been held and Douglas’s mother was returned for a second term as the MEP for Strathclyde. All the local newspapers carried variations of the same carefully staged photo opportunity. Carol Brady was standing on the forecourt of a big Glasgow hotel, smiling and holding a bunch of roses. Douglas was standing in the background next to the provost, his arm slung casually around a pretty blond woman’s waist. The caption named her as Elsbeth Brady, his wife.

Maureen had written to the General Register in Edinburgh, sending a postal order and Douglas’s details, asking for a fifteen-year search on the public marriage register. She remembered caring desperately when she sent the letter three months ago but now the response had arrived it was just a curiosity.

The outer door was jammed open by Audrey’s mop bucket. One of the cubicle doors was shut and a thin string of smoke rose from behind the door. Maureen tiptoed over the freshly mopped floor, locked the cubicle door and sat on the edge of the toilet, ripping the fold open with her finger.

The marriage certificate said that he had been married in 1987 to Elsbeth Mary McGregor. Maureen felt a burst of lethargy like an acid rush in her stomach.

“Hello?” called Audrey from the other cubicle, speaking in the strangled accent she reserved for addressing the management.

“It’s all right,” said Maureen. “It’s only me. Smoke on.”

When she got back to the office Liz was excited. “He phoned again,” she said, looking at Maureen as if this were great news. “I said you weren’t in today and he shouldn’t phone back. He must be mad for you.”

Maureen couldn’t be arsed responding. “I really don’t think so,” she said, and slipped his marriage certificate into her handbag.

At six o’clock Maureen phoned Leslie at work. “Listen, d’ye fancy meeting an hour earlier?”

“I thought your appointment with the psychiatrist was on Wednesdays.”

“Auch, aye,” said Maureen, cringing. “I’ll just dog it today.”

“Right, doll,” said Leslie. “I’ll get you there at, what, half-six?”

“Half-six it is,” said Maureen.

Liz helped to shut up the booth and then left Maureen to carry the day’s takings around the corner to the night safe. Maureen walked slowly, taking the long way through the town, avoiding the Albert Hospital. Cathedral Street is a wind tunnel. It’s a long slip road for the M8 motorway and was built as a dual carriageway to accommodate the heavy traffic. The tall office buildings on either side prevent cross breezes from tempering the eastern wind as it rolls down the hill, gathering nippy momentum as it crosses the graveyard and sweeps down the broad street. Maureen had misjudged the weather, her thin cotton dress and woolen jacket did nothing to keep out the cold and her toes were numb in her boots.

Louisa would be sitting behind her desk on the ninth floor of the Albert right now, her hands clenched in front of her, watching the door, waiting for her. Maureen didn’t want to go. The echoey corridors and smell of industrial disinfectant freaked her every time, reminding her of her stay in the Northern. The nurses there were kind but they fed her with food she didn’t like and dressed her with the curtains open. The toilets didn’t have locks on them so that the patients couldn’t misuse the privilege of privacy for a suicide bid. When she first got out, each day was a trial: she was terrified that she might snap and again be a piece of meat to be dressed every morning in case of visitors. Her current therapist, Dr. Louisa Wishart, said that her terror was a fear of vulnerability, not loss of dignity. And every time she went to see Louisa the same fifty-year-old underweight man was sitting in the waiting room. He kept trying to catch her eye and talk to her. She cut her waiting time as thin as possible to avoid him, sitting in one of the toilets or hovering around in the lobby.

She had been attending the Albert since Angus Farrell at the Rainbow Clinic referred her eight months before. By the time she had her first session with Louisa she knew she was going to be all right, that therapy was an empty gesture to medicalize a deep sadness. She tried to stop going to Louisa but her mother, Winnie, caused an almighty fuss, phoning her four times a day to ask how she was. She went back to the Albert and said she had been resisting a breakthrough in her therapy.

Having been brought up Catholic she felt like she had always been passing her inner life in front of someone or other for approval. So she lied, changing the names and making up story lines to entertain herself. She rarely talked about her family. Louisa smiled sadly and gave her obvious advice.

She took a cutoff to the High Street and walked down to the Pizza Pie Palace, a badly Americanized restaurant destined for insolvency from the first. The walls were varnished red brick, hung with chipped tin adverts for cigarettes and gasoline. Two battered papier-mâché cacti stood on either side of the door. The bonnet of a Cadillac had been unwisely attached to the wall just above the till, at forehead level. She could see Leslie sitting at a table at the back of the room, still wearing her battered biker’s leathers, with two enormous cocktails in front of her and a cigarette in her hand. Her short dark hair was kept perpetually dirty by her crash helmet and stuck out in all directions. Her nose was flat and broad, her eyes were large and deep brown, verging on black, her teeth were big and regular. The overall effect was mad and sexy. She pushed one of the cocktail glasses toward Maureen as she walked over to the table.

“Aloha.” She grinned.

A shiny-faced young waiter came over to the table and interrupted Leslie’s pizza order to tell her he thought her leathers were sexy. Leslie blew a column of smoke at him. “Get us a fucking waitress,” she said, and watched as he walked away.

“Leslie,” said Maureen, “you shouldn’t speak to people like that. He doesn’t know what he’s done to offend you.”

“Fuck him, he can work it out for himself. And if he can’t, well, he’ll be offended and that makes two of us.”

“It’s rude. He doesn’t know what he’s done.”

“You are correct, Mauri,” she said, “but I think that the important lesson for our young friend to learn is that I’m a rude woman and he should stay the fuck out of my face.”

A bouncy young waitress came over to the table. Leslie ordered a large crispy pizza for the two of them to share with anchovies, mushrooms and black olives. Maureen ordered a carafe of their cheapest red wine.

Unlike Liz, Leslie was great to talk to. Whatever had happened she unconditionally took her pal’s side, happily bad-mouthed the opposition and then never mentioned it again, but she hated Douglas and she was pleased now that Maureen said she wanted to finish it. “He’s an arse.” She fished a cherry out of her glass with her fingers. “That was abuse. You were a minute out of hospital when he nipped you.”

“He didn’t nip me,” said Maureen. “I nipped him.”

“Doesn’t matter. Getting involved with a patient is abuse.”

“But I wasn’t his patient, though,” said Maureen, instantly defensive. “I was Angus’s patient.”

“He met you at the clinic, didn’t he?”

“Yeah,” Maureen conceded uncomfortably.

“And it’s a clinic for victims of sexual abuse?”

“Yeah.”

“And he worked there and knew you were a patient?”

“Yeah, but —”

“Then it’s abuse,” said Leslie, and, lifting the cocktail, drank it far too quickly.

“Oh, I dunno, Leslie, everything can’t be abuse, you know? I mean, I wanted it. I was as much part of it as he was.”

“Yeah,” she said adamantly. “Everything can’t be abuse but that was. Do you think he could have guessed that your consent was compromised by being four months out of a psychiatric hospital?”

“I dunno.”

“Maureen, four months out of the laughing academy, come on, even a prick like Douglas knows it’s not right. He’s with someone else, he asks you to keep it a secret, he’s got a lot of power over you. It’s abusive.”

“He didn’t ask me to keep it a secret, actually,” said Maureen, blushing with annoyance.

“Did he take you home to meet his mum?” Leslie smiled softly. “What’s your damage about this guy, Mauri? He’s got access to your fucking psychiatric record, how equal can that be?”

The waitress brought the carafe of wine and poured it for them as if it was nice. She lifted the empty cocktail glasses. Maureen couldn’t think of anything to say. She nursed her cigarette to mask her discomfort, rolling the tip on the floor of the glass ashtray. Leslie was right. Douglas was a sad old wanker.

The carafe was half-empty by the time the giant pizza arrived. They ate it with their fingers, catching up with the news and gossip. The funding to the domestic violence shelter where Leslie worked had been cut and it might have to shut in a month. She was conducting a campaign to have the funding reinstated and was getting the rubber ear everywhere. “God, it’s depressing,” she said. “We got so desperate we even sent a mail shot to the papers telling them that eighty percent of battered women are turned away as it is, and not one of them phoned us. No one seems to give a shit.”

“Can’t you ask the women to speak to the papers? I bet they’d cover a human interest story.”

Leslie drained a glass of wine and thought about it. “That’s a hideous idea,” she said flatly. “We can’t ask these women to prostitute their experience for our sake. They’ve been used all their lives and most of them are still being hunted down by their own personal psychopath.”

“Auch, right enough.” Maureen sat forward. “I can’t help thinking that we never win the abortion debate at a media level because the antiabortionists coach women to cry on telly and use photographs of dead babies and we always use statistics. We should use emotive narratives and arguments.”

Leslie grinned. It must be very cheap wine, her teeth were stained dark red. Maureen supposed hers must be too.

“Frothy emotionalism,” said Leslie. “Best way to engage the ignorant.”

“Precisely. You should do that.”

“I’m sick of trying to win arguments,” said Leslie quietly. “I don’t understand why we don’t all just band together and attack. Doris Lessing says that men are frightened of women because they think women’ll laugh at them and women are frightened of men because they think men’ll kill them. We should all turn rabid and scare the living shit out of them — let them see what it feels like.”

“But what justification would there be for adopting violent tactics?”

“Negotiations,” said Leslie, adopting a Belfast accent, “have irretrievably broken down.”

“I don’t accept that,” said Maureen. “I think what you mean is you’ve lost patience.”

It was unfair of Maureen to say that: Leslie worked in the shelter with women who had been systematically beaten and raped by their partners. In Leslie’s world men rape children, they kick women in the tits and teeth and shove bottles up their backsides; they steal their money and leave them for dead and then feel wronged when they leave. If anyone could justifiably lose patience Leslie could.

Leslie thought about it for a minute. She looked despairingly at her glass and struggled with some thought. Her face collapsed with exhaustion. “Fuck it,” she said. “Let’s get really pissed.”

And they did.

Maureen’s head was fuzzy with red wine. She put on her softest T-shirt straight from the wash to make herself feel coddled and went to bed. She took more than the prescribed dose of an over-the-counter liquid sleeping draft and fell asleep with her eye makeup half-off and her leg hanging out of the bed.

2

DOUGLAS

DOUGLAS WAS TIED INTO THE BLUE KITCHEN CHAIR WITH SEVERAL strands of rope. His throat had been cut clean across, right back to the vertebrae, his head was sitting off center from his neck. Splashes and spurts of his blood were drying all over the carpet. One long red splatter extended four feet diagonally from the chair, slashing across the arm of the settee and nearly hitting the skirting board on the far wall.

She couldn’t seem to move. She was very hot. She had been scuttling back down the hall from the toilet when the blood-drenched cagoul lying just inside the living-room door caught her eye. A trail of bloody footprints led to Douglas, tied to the chair in the dead center of the room. The footprints were small and regular, like a dance-step diagram.

She didn’t remember sliding down the wall into a fetal crouch. She must have been there for a while because her backside was numb. She couldn’t see him now, just the cagoul and two of the footprints, but the sweet heavy smell of blood hung like a fog in the warm hall. The yellow plastic cagoul was drenched in blood. The hood had been kept up; the blood pattern on the rim was jagged and irregular.

He could have been there all night, she thought. She’d gone straight to bed when she got in. She’d slept in the same house as this.

Eventually, she got up and phoned the police. “There’s a dead man in my living room. It’s my boyfriend.”

She was standing still next to the phone, sweating and staring at the handle on the front door, afraid to move in case her eyes strayed into the living room, when she heard cars screaming to a stop in the street and people running up the stairs. They hammered on the door. She listened to the banging for two long bursts before she could reach over and open it. She was trembling.

They moved her into the close and asked her where she had been in the house since coming in. A photographer took pictures of everything.

Her neighbor, Jim Maliano, came out to see what the noise was. She could hear him asking the policemen questions in his Italian-Glaswegian rat-a-tat accent but couldn’t make out what he was saying. Maureen was finding it hard to speak without drawling incomprehensibly. She felt as if she were floating. Everything was moving very slowly. Jim brought her out a chair to sit on, a cup of tea and some biscuits. She couldn’t lift the cup from the saucer because she was holding the biscuits in her other hand. She put the cup and saucer down on the ground, under her chair so that no one would knock it over, and balanced the biscuits on her leg.

The neighbors from downstairs gathered vacantly on the half-landing, standing with their arms crossed, telling each new arrival that they didn’t know what had happened, someone had died or something.

A plainclothes policeman in his early thirties with a Freddie Mercury mustache and piggy eyes cautioned Maureen.

“You don’t need to caution me,” she mumbled, standing up and dropping her biscuits. “I haven’t done anything.”

“It’s just procedure,” he said. “Right, now, what happened here?”

He said yes to everything she told him about Douglas as if he already knew and was testing her. He interrupted Maureen as she tried to explain who she was. “You lot,” he said tetchily to the assembled neighbors, “you’ll be contaminating evidence there. Go back indoors and wait for an officer to come and see you. Give your names and addresses to her.” He gestured to a uniformed policewoman and turned back to Maureen. She threw up, narrowly missing the policeman’s face but hitting him squarely in the chest, and passed out.

It took her a minute to work out where she was. It was a large bed, a black-lacquered mess with small tables attached at either side. It looked like the devil’s bed. Jim Maliano was third-generation Italian immigrant and proud. His house was a shrine to Italian football and furniture design. On the wall at the foot of the bed a black and blue Inter Milan football shirt was squashed reverently behind glass and framed with tasteful silver. It was wrinkled and fading like a decaying holy relic.

Her mother, Winnie, was sitting by her feet stroking them histrionically. Winnie liked to drink whisky from a coffee cup first thing in the morning and most days were a drama from start to finish. She coughed a sob when she saw Maureen open her eyes. “Oh, honey, I can’t believe it.” She slid up the bed, cupped Maureen’s face in her hands and kissed her forehead. “Are you all right?”

Maureen nodded.

“Sure?” Winnie’s breath stank of Gold Spot.

“Aye.”

“What on earth happened?”

Maureen told her about finding the body and passing out in front of the policeman. Winnie was listening intently. When she was sure Maureen had finished talking she said that Jim had left a wee brandy for her, for the shock. She lifted an alcoholic’s idea of a wee brandy from the side table.

“Mum, I’ve just thrown up.”

“Go on,” said Winnie, “it’ll do you good.”

“I don’t want it.”

“Are you sure?”

“I don’t want it.”

Winnie shrugged, paused and sipped.

“It’s good brandy,” she said, as if the quality of drink had ever made a difference. Maureen would phone Benny and get him to come over. Benny was in Alcoholics Anonymous and Winnie couldn’t stand to be in the same house as him.

Winnie sipped the brandy, nonchalantly taking bigger gulps faster and faster until it was finished while Maureen got up and dressed. Jim had left out a Celtic football shirt and black jogging trousers for her. She took off her sticky T-shirt and slipped them on. Just as she was tying the drawstring on the trousers she caught sight of herself in the full-length mirror on the far wall. She had one panda eye from last night’s makeup and her hair was dirty and stuck to her head. She had only washed it the morning before. She ran her index finger under her eye, wiping off the worst of the nomadic mascara.

The mustachioed policeman looked around the door. The front of his jacket and shirt were wet, he had washed Maureen’s vomit off too vigorously and although he had tried to pat them dry the jacket lapels were losing their shape and his shirtfront was see-through. Maureen could see an erect nipple clinging to the wet material. “Are you decent?” he said, looking her up and down.

He was followed into the room by the policewoman and an older officer with rich auburn hair flecked with gray. Maureen had seen him directing the Forensics team. His pale face was dotted with orange freckles, oddly boyish in such a serious man. He had a big gap between his two front teeth and watery china blue eyes. She remembered him for his courtesy when he moved her into the close.

“I don’t usually dress like this,” said Maureen, smiling with embarrassment at her outfit. “Can I get my own clothes?”

“Is that what you were wearing last night?” asked the Mustache, gesturing to the discarded T-shirt on the bed.

“Um, yeah.”

He pulled a folded white paper bag out of a pocket and took a Biro from his breast pocket. He slid the pen under the T-shirt and poked it into the bag.

“We’d like you to come with us, Miss O’Donnell,” said Mustache Man. “We’d like to talk to you at the station.”

“You can’t arrest her!” shouted Winnie, her voice a startling wail.

“We’re not trying to,” said the policewoman calmingly. “We’re just asking her to talk to us. If she comes down to the station it’d be voluntary.”

Winnie put out her hand in front of Maureen in a dramatic, brandy-induced gesture of maternal protectiveness. “I demand that you allow her to see a solicitor,” she said.

Maureen shoved Winnie’s hand out of the way. “Stop it, Mum,” she said, and turned back to the police officers. “I’ll come down with you.”

Jim Maliano watched from the living-room doorway as the motley crowd walked down the dark hall. When Maureen came past him he reached out and squeezed her shoulder gently. His small gesture of empathy touched Maureen unreasonably and she vowed not to forget it.

The rest of it was a bit of a blur. She remembered Winnie crying loudly and a small crowd parting outside the close to let her through. The red-haired man got into the driver’s seat of a blue Ford and the policewoman helped Maureen into the backseat, climbing in next to her. He asked if she had been cautioned. She said she had but she wasn’t really listening. He recited it for her. Within minutes they were in Stewart Street police station.

It was just round the corner from her house but Maureen hadn’t paid much attention to it before. The three-story concrete building sat on the edge of an industrial estate and was fronted with reflective glass. It looked more like an office block than a police station. They drove round to the back and pulled into a small car park. It was surrounded by a high wall topped with spiraled razor wire. Looking up at the back of the building from the car park, she could see small, mean, barred windows.

The red-haired man helped her out of the car, holding on to her elbow longer than he need have. She must look a bit wobbly. “Now, don’t you worry,” he said. “That’s the worst bit over. We’re only going to talk to you.”

But Maureen wasn’t thinking about that. She just wanted to see Liam.

3

MARIE, UNA AND LIAM

MAUREEN WAS THE YOUNGEST OF THE FOUR OF THEM. THEY ALL bore a striking family resemblance: dark brown hair, square jaws and fat button noses. Their build was the same too: they were all short and thin. When they were children, people often mistook Liam and Maureen for twins: they had been born ten months apart, both had pale blue eyes and they spent so much time together they adopted all of the same mannerisms. When they hit puberty Liam refused to hang about with Maureen. She didn’t understand: she followed him around like a little dog until he threatened to beat her up and stopped talking to her. Their resemblance gradually faded.

Marie was the eldest. She moved to London in the early eighties to get away from her mum’s drinking, settled there and became one of Mrs. Thatcher’s starry-eyed children. She got a job in a bank and worked her way up. At first the change in her seemed superficial: she began to define all her friends by how big their mortgage was and what kind of car they drove. It took a while for them to realize that Marie was deep down different. They didn’t talk about it. They could talk about Winnie’s alcoholism, about Maureen’s mental-health problems, and to a lesser extent about Liam dealing drugs, but they couldn’t talk about Marie being a Thatcherite. There was nothing kind to be said about that. Maureen had always assumed that Marie was a socialist because she was kind. The final break between them came the last time Marie was home for a visit. They were talking about homelessness and Maureen ruined the dinner for everybody by losing the place and shouting “Get a fucking value system!” at her sister.

It happened six months before Maureen was taken to hospital, but the way Marie told it there was only a matter of weeks between one incident and the other. And that explained it. Maureen was mental and Marie forgave her.

Marie was married to Robert, another banker, who worked in the City. They had been married on the quiet in the Chelsea Register Office two years before but Robert had never found the time to come to Glasgow and pay his respects to her family. It was a shame because now he couldn’t afford to: he had become a Lloyd’s Name at just the wrong time, on just the wrong syndicate, and they were living in a bedsit in Bromley.

Una’s husband, Alistair, was an integral part of the family. He was a plumber and couldn’t believe his luck when Una agreed to marry him. He was a quiet, honorable man and, to Una’s everlasting joy, had proved himself eminently malleable. She began by changing the way he dressed, then moved on to his accent, and at the moment she was trying to change his career.

Una was a civil engineer and made a right few quid. She scheduled beginning a family for 1995 and had virtually booked her maternity leave but she didn’t get pregnant. She put a brave face on it but recently she had confided in them all, individually and in confidence, that she was getting desperate. Maureen went with her to the clinic when she had the preliminary tests. It turned out that Alistair’s sperm count was a bit low and he was put on a course of medication. Una was happy and Alistair was if she was.

When it came time for Liam to go to secondary school, Michael, their father, had lost his job as a journalist because of his drinking, quite a feat in those days. They couldn’t afford to send Liam to the private school Marie and Una had been to so he was sent to Hillhead Comprehensive and Maureen followed him a year later. It was a good school but neither of them studied very hard.

Winnie’s alcoholism progressed rapidly after Michael left them. Within four years she was married again and their new stepfather, George, became the silent partner in loud, brutal arguments. Despite the atmosphere in the house Liam delighted his mother by getting into Glasgow University Law School. He dropped out after six months and started selling hash to his friends on a casual basis but he discovered a talent and went professional. He bought a big house. They told Winnie he managed bands. Maureen used to nag him about security in the house but he said that if he started to worry about things like that he’d get really paranoid.

His present girlfriend, Maggie, was a bit of a mystery. She was a model, but they never saw her model anything, and a singer, but they never heard her sing either. She was very pretty and had the roundest arse Maureen had ever seen. She didn’t seem to have any friends of her own. Poor Maggie had a lot to live up to: Lynn, Liam’s first and last girlfriend, was a doctor’s receptionist and as rough as a badger’s arse but such great crack even Winnie’s snobbishness dissipated when Lynn told a story.

Maureen did well at school and went straight to Glasgow University to study history of art. She was in her final year when she began to think she was schizophrenic. The night terrors she had always suffered from got progressively worse and she started having waking flashbacks. They were mild at first but escalated in frequency

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...