- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

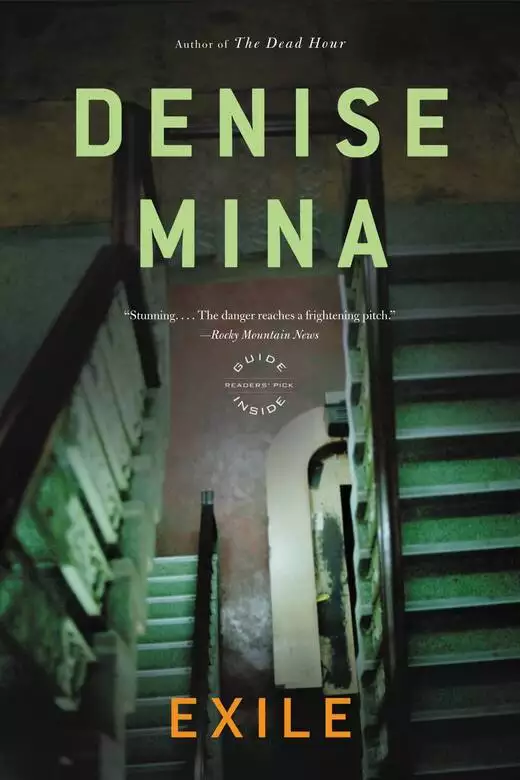

Synopsis

The last time that Maureen O'Donnell saw Ann Harris she was nursing a couple of broken ribs and reeking of alcohol at the women's shelter. Now Ann has turned up dead hundreds of miles away, in London. Eager to escape some family difficulties of her own, Maureen travels to London to determine the circumstances of Ann's brutal death. In the seedy underworld of criminal exiles and dangerous drug lords, Maureen tries to piece together the horror of Ann's last days - and to save herself from a similarly ugly fate. The suspense ratchets up, as with visceral shock and grim wit Denise Mina secures her place among the top-ranking writers of crime fiction today.

Release date: October 10, 2007

Publisher: Back Bay Books

Print pages: 452

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Exile

Denise Mina

was pressed tightly against hers and his hand was under her thigh. The cumulative heat was itchy and damp. She peeled their

skins apart, trying hard not to wake him, but he felt her stir. He peered around at her through sleep-puffed eyes.

“’Kay?” he murmured.

“Yeah,” breathed Maureen.

She waited, watching her milky breath hover above her, listening to the wind hissing outside. Vik’s breathing deepened to

a soft, nasal whistle and Maureen slid into the bitter morning.

She flicked on the kettle, lit a cigarette and looked out of the kitchen window. January is the despairing heart of the Scottish

winter and black clouds brooded low over the city, pregnant with spiteful rain. It came to her every morning now; it was the

first thought in her head when she opened her eyes. After a wordless fifteen-year absence, Michael, her father, was back in

Glasgow.

They only found out afterwards that their elder sister Marie hadn’t bumped into Michael in London. She’d gone looking for

him, contacting the National Union of Journalists and putting adverts in the Evening Standard. She found him living in the Surrey Docks in a high-rise council flat carpeted with empty lager cans. He was troubled with

his health and hadn’t worked for a long time so Una paid his fare home. Maureen told them she wouldn’t see him but her insistence

was needless. Liam said Michael never mentioned her, had never once spoken her name and ignored it when anyone else did. Even

their mother, Winnie, was starting to wonder about that. Maureen couldn’t get over the injustice of it. Michael was back in

the bosom of the family and she was outcast.

The moment she heard he was home everything changed for her. It wasn’t like the breakdown: she wasn’t flashing back all the

time and she knew it wasn’t depression. It was a limitless, aching sadness that marred everything she cast her eye over. She

couldn’t contain it: her eyes had become incontinent, dripping stupid tears into washing-up, down her coat, into shopping

trolleys. She even cried while she slept. When she stood at the window in Garnethill and looked down over Glasgow she felt

her face might open and flood the city with tears. Grief distracted her entirely; it was as if her life continued in an adjacent

room—she could hear the noises and see the people but she couldn’t participate or care about any of it.

Vik snored loudly once and stopped. He was the only thing in her life that wasn’t about the past but it was the wrong time

for a fresh chapter and coy new discoveries. Maureen was seeing her father everywhere, grieving for Douglas and missing Leslie

desperately. Vik knew almost nothing about her, nothing about Douglas being murdered in her living room six months ago, or

Michael’s late-night visits to her bedroom when she was a child, nothing about the schism in her family. Telling about Michael

was the worst moment with new boyfriends: she saw them change towards her, saw them feel confused and implicated. Douglas

had been different because he was a therapist. She’d never had to explain away the nightmares or the irrational phobias. Douglas

was as soiled and melancholy as herself and Vik was a big, jolly boy.

She looked out of the window, took a deep draw on her fag and heard the swish of paper scraping through metal, followed by

a light thud on the hall carpet. She recognized the blue hospital envelope at once—Angus was keeping busy. She picked it up

and went back into the kitchen, sat down and lit a fresh cigarette from the dying tip of the old one. The envelope was made

of cheap porous paper, her name and address written in a careful hand. She leaned across to the bills drawer and pulled out

the pile of blue envelopes, laying all fifteen in chronological rows on the table. The writing was changing, becoming more

controlled. He was getting better. Some of his letters were threatening, mostly they were gibberish, but the threats and the

gibberish were evenly interspersed, regular and anticipatable. She knew the voice of random insanity from her own time in

mental hospital and this wasn’t it. He was a rapist and a murderer, but she wasn’t afraid of him and she didn’t give a shit.

He was locked away in the state mental hospital. It was like being challenged to a dancing competition by a brick. Wearily,

she gathered the unopened letter together with the old ones and shoved them into a drawer. She could read it later.

“Maureen?” Vik called sleepily from the bedroom. “Maureen?”

She stubbed out her fag and tried to find her voice. “Yeah?” She sounded tense.

“Maureen, come here.”

She stood up. “What for?” she called.

“I’ve got something for you.” Vik was grinning.

She brushed the hair off her face. “What sort of thing?” she said, forcing the playfulness. If she could act normal she might

feel normal.

LONDON IS A SAVAGE CITY AND SHE DIDN’T BELONG THERE. SHE MIGHT never have been found but for Daniel. She would have disappeared completely, a missing splinter from a shattered family,

a half-remembered feature in a pub landscape.

Daniel was having a good morning. It was a sunny January day and he was on his way to his first shift as barman in a private

Chelsea club favored by footballers and professional celebrities. The traffic was sparse, the lights were going his way and

he couldn’t wait to get to work. He slowed at the junction, signaling right to the broad road bordering the river. He took

the corner comfortably, using his weight to sway the bike, sliding across the path of traffic held static at the lights. He

was about to straighten up when he saw the silver Mini careering towards him on his side of the road, the wheel-trim spitting

red sparks as it scraped along the high lip of the pavement. He held his breath, yanked the handlebars left and shot straight

across the road, up over the curb, slamming his front wheel into the low river wall at thirty miles an hour. The back wheel

flew off the ground, catapulting Daniel into the air just as the Mini passed behind him. He back-flipped the long twenty-foot

drop to the river, landing on a small muddy island of riverbank. The tide was out, and of all the urban rubble in the Thames

he might have landed on, Daniel found himself on a sludge-soaked mattress.

He did a quick stock-take of his limbs and faculties and found everything in order. He thanked God, remembered that he didn’t

believe in God and took the credit back for himself. Staggered at his skill and reflexive dexterity, he pushed himself upright

on the mattress, his left hand sliding a viscous layer off the filthy surface. Gathering the mulch into his cupped hand, he

squeezed hard with adrenal vigor. A crowd of concerned passersby were leaning over the sheer wall, shouting frantically down

to him. Daniel waved. “Okay,” he shouted. “Don’t worry. Other bloke all right?”

The pedestrians looked to their left and shouted in the affirmative. Daniel grinned and looked down at his feet. He was sitting

on a corpse, the heel of his foot sinking into her thigh.

He scrambled to his feet, shaking the mattress, making her arm fall out onto the muddy bank. She was wearing a chunky gold

identity bracelet with “Ann” inscribed on it. He staggered backwards towards the river, keeping his eyes on her, trying to

make sense of the image.

He could see her now, a bloated pink and blue belly and a void of a face framed by stringy gray hair, drained of color by

the rapacious water. A ragged handful of custard skin was missing from her belly. Daniel called out, a strangled animal cry,

and flailed his left hand in the air, scattering her disintegrating flesh. He crouched and splashed his hand in the brown

water, trying to wash away the sensation. Panting, he turned back and pointed at the rotting thing hanging out of the mattress.

A man shouted to him from the high river wall. “Are you injured?”

Daniel looked up. His eyes were brimming over. The man’s head was an indeterminate blob floating above the river wall. Daniel’s

eyes flicked back to the corpse, startled afresh by its presence.

The well-meaning man was shouting slowly, enunciating carefully. “Can you hear me?” he yelled. “I am a first-aider.”

Daniel tried to look up but each time his eyes flicked back to her. He imagined she had moved and fear took the breath from

him. He started to cry and looked up. “Are you the police?” he shouted, in a voice he barely recognized.

“No,” shouted the man. “I am a first-aider. Do you require medical attention?”

“Get the fucking police!” screamed Daniel, his eyes streaming now, his nose running into his mouth. He shook his hand in the air, his skin burning

with disgust. “Get the fucking police.”

A STARK WIND STREAMED INTO GLASGOW TUGGING BLACK RAIN clouds behind it. Litter fluttered frantically outside the strip of glass and the close door breathed gently in and out.

The students kept their heads down as they worked their way up to the art school. Maureen cupped her scarf over her ears and

turned up her stiff collar before opening the door and venturing out. The bullying wind buffeted her, making her totter slightly

as she turned to shut the door. She kept her fists tight inside her silken pockets and made her way down the hill to the town,

cozy in her rich-girl overcoat.

She had bought the coat in a pre-Christmas sale. It was pure black wool with a gray silk lining, long and flared at the bottom

with a collar so stiff that it stood straight up and kept the wind off her neck. It was the most luxurious thing she had ever

owned. Even at half price it had cost more than three months’ mortgage. She swithered in the shop but persuaded herself that

it would last three winters, maybe even four, and anyway, she enjoyed losing the money. On the day Angus murdered him, Douglas

had deposited fifteen thousand pounds in her bank account. It was a clumsy act of atonement for their affair and the money

compromised her. She knew that the honorable thing to do was give it away but she was dazzled by the string of numbers on

her cash-point receipts and kept it, justifying her avarice by doing voluntary work for the Place of Safety Shelters. She

was hemorrhaging money, leaving the heating on all night, smoking fancy fags, buying endless new cosmetic products, fifty-quid

face creams and new-you shampoos, trying to lose it without having the courage to give it away.

The biting wind made her eyes burn and run as she crossed the hilt of the hill. Leslie would be coming into the office today

and Maureen was dreading meeting her.

“Maureen?”

Someone was shouting after her, their voice diluted by the wind. She turned back. A woman in a red head scarf walked quickly

over to her, keeping her head down, stepping carefully over the icy ground. She stopped two feet away from Maureen and looked

up. “Maureen, I love you.”

“Please,” said Maureen, fazed and wary, “leave me alone.”

“I need to see you,” said Winnie.

“Mum, I asked ye to stay away,” insisted Maureen. “I just want ye to leave me alone.”

Winnie grabbed her, squeezing her fingertips tight into the flesh on Maureen’s forearm. She was drunk and had been crying

for hours, possibly days. Her eyes were pink, the lids heavy and squared where the tear ducts had swollen beneath them. A

gaggle of pedestrians hurried past, coming up the steep hill from the underground, walking uncertainly on the slippery ground.

“I love you. And look”—Winnie held a silver foil parcel towards her and clenched her teeth to avert a sob—“I’ve brought you

some roast beef.” Winnie poked the package towards her but Maureen’s hands stayed in her pockets.

“I don’t want beef, Mum.”

“Take it,” said Winnie desperately. “Please. I brought it over for you. The juice has run in my handbag. I made too much—”

A passing woman skidded slightly on the frosty ground, let out a startled exclamation and grabbed Winnie’s arm to steady herself.

She dragged Winnie over to one side, jerking her hand and knocking the lump of silver onto the pavement. The cheap foil burst,

scattering the slices of brown meat, splattering watery blood over the white ice.

“Oh, my.” The woman giggled, nervous with fright, patting her chest as she stood up. “Sorry about that. It’s so icy this morning.”

Winnie yanked her arm away. “You made me drop that,” she said, and the woman smelled her breath, greasy with drink at nine

in the morning.

She glanced over Winnie’s shoulder to Mr. Padda’s licensed grocer’s, shot Winnie a disgusted look and stood up tall and straight.

“Didn’t mean to touch you,” she said perfunctorily.

“Go away,” said Winnie indignantly.

“I’m sorry,” the woman addressed Maureen. “I slipped—”

“We didn’t ask for your life story,” snapped a suddenly nasty Winnie.

Maureen couldn’t help herself. It was a big mistake but she smiled at Winnie’s appalling behavior and gave her quarter. The

disapproving woman took to her heels and scuttled away, watching her feet on the icy ground. Maureen took Winnie’s arm and

guided her out of the busy thoroughfare and onto the side of the pavement.

“Thank you, honey,” said Winnie, covering Maureen’s hand with her own.

Maureen wanted to turn and walk away. Every time she had seen Winnie before the schism Winnie hurt her or freaked her out

or had done her head in in one way or another. She dearly wanted to walk away, but looking at her mum’s badly applied makeup,

at her shiny nose and big mittens, Maureen realized that she’d missed her terribly, missed all the fights and the high drama

and the mingled smells of vodka and face powder. “Mum,” she said, “I’m not staying away from you because you don’t love me.”

Tears were running down Winnie’s face and her chin began to tremble. “Why, then?” she demanded, catching the eye of a workman

on his way into the newsagent’s.

“You know why,” said Maureen.

Winnie wiped her face with her mittens, scarring the beige suede with her tears. “You know about Una?” she asked.

“I know she’s pregnant. Liam told me.”

Winnie sniffed, wringing her hands. “And what did you do on Christmas Day?” she asked.

Maureen shrugged. “Had dinner with friends,” she said.

She had spent the day alone with a packet of Marks & Spencer’s sausage rolls, which she had eaten and hadn’t liked at all.

An hour later she had read the back of the packet and realized she was supposed to have cooked them. Liam had come over in

the evening and they had watched the tail end of the good television together and had a smoke. He had refused to eat with

the family because Michael would be there. Liam said George, their stepdad, had almost come out with him. George didn’t like

Michael either and he liked everyone. George would have liked Old Nick if he could hold a tune and got his round in.

“It’s because of your father, isn’t it? We hardly see him now,” said Winnie. “He isn’t very nice.”

But Maureen didn’t want to know. She didn’t want one more scrap of information for her subconscious to build nightmares around.

“Mum,” she said, trying to stick to the point, “it pains me to see you, do you understand?”

Winnie pressed her hankie to her mouth. “How do I pain you?” she said, as her face crumpled. “What have I ever done?”

“You know fine well.”

“No,” wept Winnie, “I don’t know fine well.”

“How could you have him back in your house after what he did to me? I’ll never understand that. I know you don’t believe me

but if you even wondered about it—”

Winnie took a deep wavering breath, snapped her wrist out and slapped Maureen’s arm. “At least phone—”

“Don’t fucking slap me, Mum!” shouted Maureen. “I’m an adult. It’s not appropriate.”

Winnie began to sob, making Maureen into the sort of person who would shout unkind things at her crying mother. She had promised

herself peace from this but here she was, falling into the old traps, playing the bad guy again, coming to hate herself on

a whole new level.

“We don’t see him anymore”—Winnie struggled to speak through convulsive sobs—“and Una’s angry and George won’t speak to me… I miss you, Maureen. I don’t want you to not see me.”

Maureen wondered at Winnie’s resilience. If Winnie had set her mind to world domination she could have done it. Unhampered

by the twin evils of manners or empathy, Winnie could railroad an acre of salesmen into charity work if she set her mind to

it.

“Mum,” she said softly, “I don’t want to see you for a while and that continues to be true, whether or not you’re all having

a nice time together.”

Winnie clocked the condition. She looked up when Maureen said it would only be for a while and looked away again. She blew

her nose and narrowed her eyes at Maureen. “Don’t you tell me what to do,” she said, hope twitching at the corners of her

mouth. “You’re still a cheeky wee besom. And I’ll slap ye if I want to. I could take you in a fight any day.” She looked at

the spilled meat, scattered and trampled by passing feet. “Are ye sure ye won’t have a slice?”

Maureen started to smile but her eyes began to water and she had to breathe in deeply and blink hard to stop herself crying.

It was good news: they weren’t getting on, he had nothing to keep him here, no reason to stay. Winnie took off one of her

mittens and played with her hankie, pulling at the corners, looking for a dry patch. The wedding band George had given her

was loose on her finger. Winnie was losing weight; her skin looked thin and a watery gray liver spot was developing on a knuckle.

Maureen reached out suddenly and held her mum’s hand, cupping it in her own, trying to hold the warm in. The wind blew freezing

tears across her face like racing insects. “Mum,” she breathed. “My mum.”

They stood close, looking at Winnie’s hand, chins trembling for love of each other, crying for the pointless sadness of it

all.

“I can’t stand this,” whispered Maureen.

“Me neither,” said Winnie.

But she meant the moment and Maureen meant her life. Winnie reached up to Maureen’s face, dabbing at her wet ear like a drunken

St. Veronica, letting her fingers linger on her cheek.

Maureen sniffed hard, dragging the cold air up to her eyes, waking herself up. “Is he going back to London, then?”

“Don’t think so,” said Winnie.

“Who’s keeping him here?”

Winnie tutted at her. “No one’s keeping him here,” she said. “He’s got a flat, a council flat, in Ruchill.” She pointed over

Maureen’s shoulder to the horizon, to the jagged red-brick tower of the old Ruchill hospital.

Maureen could see it from her bedroom window. She dropped Winnie’s hand. “What the fuck did you tell me that for?”

Winnie shrugged carelessly. “It’s where he is.”

“I don’t want to know anything about him and you come here and tell me he lives near me?”

Winnie knew she was in the wrong. She tugged her mitten back on and pressed her face up to Maureen’s. “Did it ever occur to

you,” she said, “that the rest of us know him as well?”

“What?”

“It’s not all about you,” shouted Winnie. “He’s their father too. Don’t you think they wonder about him? Don’t you think I

wonder?”

“Wonder?” shouted Maureen. “You stupid cow! D’ye think I was committed to a psychiatric hospital suffering from pathological

wonder?”

“Don’t you cast that up to me.” Winnie held up her hand. “Your breakdown wasn’t just about him. You were always a strange

wee girl. You were always unhappy.”

They hadn’t seen each other for five months and although Maureen vividly remembered how angry her mother made her, she had

forgotten the sanctimonious bulldozing, the utter disregard for her feelings, the vicious kindness and blind denial of what

Michael had done.

“Think about it, Winnie,” she said, talking through her teeth, the fury reducing her voice to a whisper, “think about what

he did to me. If it wasn’t for him I’d never have been so unhappy. If it wasn’t for him I’d never have been in hospital. I’d

have gone on to a real job after my fucking degree. I might be happy, I might be married. I might even have the nerve to hope

for children of my own. I might be able to sleep. I might be able to look at myself in the fucking mirror without wanting

to scratch my fucking face off.” She was out of control, shouting loud and crying in the street. Art students stole glances

at her as they came out of Mr. Padda’s with their newspapers and lunchtime rolls. “And what did he sacrifice all of that for?

For a fucking tug.”

Winnie had never believed in the abuse and had never flinched from saying so before. But this time she pursed her lips and

clasped her hands prissily in front of her. “Is that all you want to say?” she said, grinding her teeth and looking off into

the middle distance.

Winnie was trying to listen. She was actually trying, and Maureen had never known her to do that. Not when they were children,

not when they were adults, not even when Maureen was in hospital. “Mum, that man and the memories and stuff. I know what he

did. He knows he did it too.”

Winnie looked nervously around her. “Do we have to discuss this here?”

“Does he ever ask for me?”

Winnie swallowed hard and looked away. She muttered something into the wind.

“What?” said Maureen.

“No,” said Winnie quietly. “He never asks for you. Ever. It’s as if you were never born.”

“How likely is that, Winnie? Doesn’t it make ye wonder?”

Winnie couldn’t think of an answer. It must have bothered her terribly. She looked angrily over Maureen’s shoulder. “I’m sick

of this,” she said.

“Why did you tell me he lives there? God, am I not troubled enough already?”

“You can’t blame me for that—”

But Maureen was backing off into the street. She leaned forward in case Winnie missed anything. “Stay away from me,” she said

slowly, pointing at her mum’s soft chest. “And stop phone-pesting me when you’re steaming.”

“If I was that bad of a mother,” Winnie shouted after her, “how come none of the rest of them had breakdowns?”

The vicious morning frost had numbed Maureen’s ears before she was two hundred yards down the hill. She turned a corner and

the wind ambushed her, parting her eyelashes. She stopped and waited at the lights, staring at the patchwork tar on the road.

The nervous cars and buses jostled one another for road space, speeding across the twenty-foot yellow box, afraid of being

left back at the lights. If she threw herself into the road she’d be killed instantly, a five-foot jump to an eternity of

peace and no more brave plowing on, no more shouting over the storm, no more nightmares, no more Michael. She thought of Pauline

Doyle and envied her.

Pauline was a June suicide. She had been in psychiatric hospital with Maureen. Two weeks after she was released, a walker

had found her dead under a tree. Maureen couldn’t stop thinking about her. Her thoughts kept short-circuiting straight from

worry to the happy image of Pauline at peace on the grass in springtime, oblivious to the insects crawling over her legs.

She glanced up, conscious that something around her had changed. The green man was flashing on and off and the other pedestrians

had almost crossed the road. She jogged after them, clutching the fag packet in her pocket, bribing herself on with the promise

of a cigarette when she got to work.

THE MORNING DRAGGED BY LIKE A STRANGER’S FUNERAL. MAUREEN found herself picking over everything Winnie had said, looking for clues about the family, guessing what she really meant.

Liam had told her that Una was pregnant, but Maureen wasn’t concerned: she knew the baby would be safe from Michael because

Alistair, Una’s husband, was so even-tempered and he had always believed Maureen about the abuse. What jarred more intensely

was Winnie trying to listen to her. Douglas used to say that Maureen was hyper-vigilant with her family, always looking for

signals and signs, clues about what was going to happen next, because nothing was predictable. He said it was a common behavioral

trait in children from disturbed backgrounds.

She couldn’t remember Douglas’s face properly anymore. All she could picture were his eyes as he smiled at her and blinked,

a strip of memory floating in a void, like an animated photofit strip. Maureen looked across the desk at Jan.

Jan was tall and blond and plump around the middle. She had an inexplicable penchant for wearing green and purple together

and giggled about it, as if she were a great character. She stayed with her parents on the south side but resented living

in their warm home and eating their groceries. Her parents had retired recently and seemed to spend their days kicking about

the house, bickering with each other about minutiae. Jan kept trying to engage Maureen in the dull stories by asking about

her own parents: did they fight, were they happy, who took out the rubbish? Maureen made up a story about a close family of

two with an adoring mother who was very religious. Their father had left them when they were very young. She didn’t remember

him but he was a sailor with a gambling habit and a beard. When Maureen saw her fictional father in her head she always imagined

him steering a fishing boat and wearing a yellow sou’wester and joke glasses with pop-out eyeballs on springs.

“Smoke?” said Jan.

“Two minutes,” said Maureen, and went back to staring at a chapter in the housing-law textbook. It didn’t make any sense.

A regulation had imported a double negative into the legislation. She was crap at this. When they had given her the job it

was because of Leslie and the posters, not because she had shown any capacity to map housing legislation or write summaries.

The few reports she had submitted were politely bounced back for revision by the committee and she knew their buoyant faith

in her was flagging.

In anticipation of the funding cut, the Place of Safety Shelters had moved to the cheapest city-center office in Glasgow.

It was an ugly, gray, windowless room. The funding cut had been deferred because of the poster campaign but the PSS stayed

there, saving their money as best they could, getting ready for the hard times ahead.

The poster campaign was one of the few selfless things Maureen had done with Douglas’s money. Leslie didn’t tell the committee

they were doing it. They plastered the city with the posters in one long night, working from west to east and finishing at

dawn. Not many people phoned the funding committee number at the bottom of the poster to protest. The picture was quite obscure

and most people didn’t know what it was about but, still, the funding cut had been deferred for six months. Everyone in the

office had been speculating about the posters after the decision was announced; Leslie called a meeting and admitted responsibility.

She told them that her pal had masterminded the scheme, paid for it all herself, and now she’d like to work for them on a

voluntary basis if they could find a place for her. They saw that Maureen had a degree and gave her the housing job. She’d

been a hero two months ago—everyone in the office wanted to talk to her. The desk she shared with Jan was right by the door

and she could hardly get a full hour’s work done on any given da

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...