- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

To be a Pure is to be perfect, untouched by Detonations that scarred the Earth, and sheltered inside the paradise that is the Dome. But Partridge escaped to the outside world, where Wretches struggle to survive amid smoke and ash. Now, at the command of Partridge’s father, the Dome is unleashing nightmare after nightmare upon the Wretches in an effort to get him back.

At Partridge’s side is a small band of those united against the Dome: Lyda, the warrior; Bradwell, the revolutionary; El Capitan, the guard; and Pressia, the young woman whose mysterious past ties her to Partridge in ways she never could have imagined. Long ago a plan was hatched that could mean the Earth’s ultimate doom. Now only Partridge and Pressia can set things right.

To save millions of innocent lives, Partridge must risk his own by returning to the Dome and facing his most terrifying challenge. And Pressia, armed only with a mysterious Black Box containing a set of cryptic clues, must travel to the very ends of the Earth, to a place where no map can guide her. If they succeed, the world will be saved. But should they fail, humankind will pay a terrible price…

An epic quest that sweeps readers into a world of beautiful brutality, Fuse continues the story of two people fighting to save their futures—and change the fate of the world.

Release date: September 10, 2013

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

Print pages: 496

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

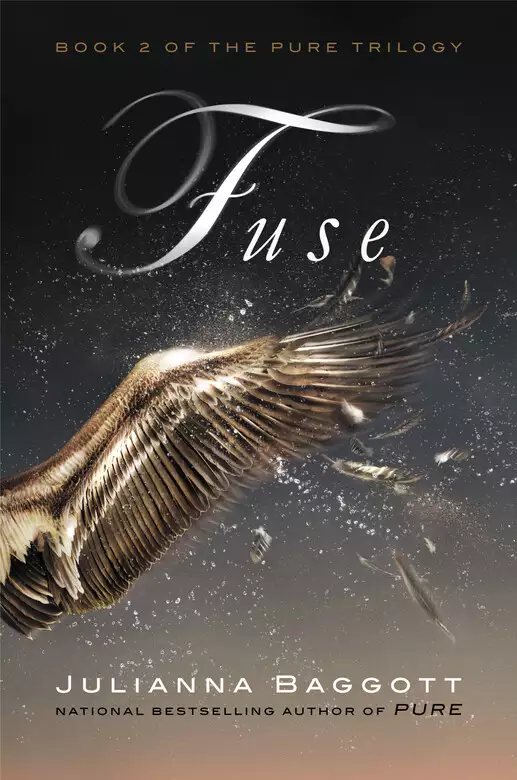

Fuse

Julianna Baggott

Lying on a thin coat of snow, she sees gray earth meeting gray sky, and she knows she’s back. The horizon looks clawed, but the claw marks are only three stunted trees. They stand in a row like they’re stapling the ground to the sky.

She gasps, suddenly, a delayed reaction, as if someone is trying to steal her breath and she’s pulling it back into her throat.

She sits up. She’s still small, still just a nine-year-old girl. She feels like she’s lost a lot of time, but she hasn’t. Not really. Not years. Maybe only days, weeks.

She tugs her thick coat in tight around her ribs. The coat is proof. She touches its silver buttons. There’s a scarf tucked down into the coat, wound twice around her neck. Who dressed her? Who wound the scarf twice? She looks at her boots—dark blue with thick laces, new—and her hands fitted into gloves, each finger encased in a taut cocoon.

A curl of her dark red hair sits on her jacket, her hair shining. The end of each strand is thick and perfect as if newly cut.

She pulls up the sleeve of the coat, exposing her arm. Just as it was under the bright light, the bone is no longer warped. There are no thin plastic ridges bubbled along the skin. She isn’t stippled with shards. Not even a mole or a freckle. Her skin is white—white, the way snow should be, maybe even whiter. She’s never seen really white snow with her own eyes. The light veins ride blue beneath the white. She touches the soft inner skin of one wrist to her cheek, then her lips. Smooth skin on smooth skin.

She looks around and knows they’re close; she can feel the electricity of their bodies filling the air. She remembers what it was like when they first took her from the other strays; motherless, fatherless, they slept in a handmade lean-to near the markets. She isn’t sure why she was chosen, lifted into the air, clutched. One cradled her in its arms and hurdled across the rubble while the others bounded around them. Its breath chugged, mechanically. Its legs pumped. Her eyes teared in the wind, so its angular face was blurry. She wasn’t afraid, but now she is. They’re here, their strong bodies buzzing like massive bees, but they’re leaving her. She feels like a child in a fairy tale. In her mother’s stories—she had a mother once—there was a woodsman who was supposed to take a girl’s heart back to an evil queen, but he couldn’t force himself to do it. Another sliced open a wolf to save the people it had eaten. The woodsmen were strong and good. But they left girls in the woods sometimes, girls who then had to fend for themselves.

Light snow falls. She stands slowly. The world lurches as if it’s suddenly grown heavy. She falls to her knees and then hears voices in the woods; two are people walking toward her. Even from this distance, she can see the red scars on their faces. One wobbles from a limp. They’re carrying sacks.

She tugs the scarf over her nose and mouth. She’s supposed to be found. She’s a foundling; she remembers this word was used in the room with the bright light. “We want her to be a foundling.” It was a man’s voice, quavering over a speaker. He was in charge, though she never saw him. Willux, Willux, people whispered—people with smooth skin who weren’t fused to anything. They moved easily around her bed, surrounded by metal posts where clear sacs of fluid were clamped and dripped into tubes, among little beeping machines and wires. It was like having mothers and fathers, too many to keep track.

She remembers the wide light in the room, its brilliant bulb, so bright and close it kept her warm. She remembers how she first ran her hand over her skin, and when she touched her stomach, it too was smooth. Her navel—the thing her mother always called the button of her belly, and what the voices in that room called her umbilicus—was gone.

She reaches up under her coat and shirt and runs her hand over her stomach. Like before, there’s only a stretch of skin and more skin.

“Healed,” the voices said behind white masks, but they were concerned. “Still, a success,” they said. Some wanted to keep her for observation.

She starts to open her mouth to call to the distant figures carrying sacks, but her mouth doesn’t open all the way. It’s as if her lips are slightly stitched on either side—the edges sealed.

And what would she say? She can’t think of any words. The words whirl in her mind. They’re furred. She can’t line them up or utter them. Finally she calls out, but the only words that form in her mouth are “We want!” She doesn’t know why. She tries again to call for help, but again she shouts, “We want!”

They walk up, two young women. They’re pickers; she can tell by the warts and scars on their fingers. They’ve touched a lot of poisonous bulbs, berries, morels. One of them has silver prongs, like those on an old fork, in place of two of her fingers. She’s the one with the limp, and her face, though seared a deep red, is strangely pretty, mostly because of her eyes, which glow a golden orange like liquid metal—stained by the brightness of the bombs themselves. She’s blind. She clutches the other picker’s arm and says, “Who’s you?” It sounds like a birdcall. The girl heard birds in the bright room, recorded and piped in by the unseen speakers. Cooing, the girl thinks, and then she hears other birds in the woods. These birds have the kinds of calls she grew up with—not clear, sweet notes as in the bright room, but scratches and rattles.

The two young women are scared of her. Can they already tell she’s different?

She wants to tell them her name, but it’s gone. The only words in her mind are Fire Flower. That’s what her mother used to call her sometimes; born from fire and destruction, she took root and grew. She’s never known her father, but she’s pretty sure that he was lost in the fire and destruction.

And then her name appears: Wilda. She is Wilda.

She puts her hand on the cold ground. She wants to tell them that she’s new. She wants to tell them that the world has changed forever. She says, “We want our son.” The words startle her. Why did she say this?

The young women look at each other. The blind one says, “What was that? Whose son?”

The other has a scar running down one cheek as if she had a braid fused to her face now covered in a layer of skin. She says, “She’s not right in the head.”

“Who’s you?” the blind one says again.

The girl says, “We want our son.” These are the only words that she can say.

The pickers look around suddenly, even the blind one. They hear the electrical synapses now, firing through the air. The creatures who took her are restless. “There’s many,” the one with the braided scar says, wide-eyed. “They’re protecting her. Can you feel ’em? They been sent by our Watchers to look over her.”

“Angels,” the blind one says.

They start to back away.

But then Wilda pulls up her sleeve and exposes her arm—so white it seems to glow. “We want,” she says again, slowly, “our son returned.”

Pressia

The lobby at OSR headquarters is dotted with a few glowing handmade oil lamps strung from the exposed beams of the high ceiling. The survivors are bedding down on blankets and mats, curled together to keep warm. Their bodies hold a collective humid heat despite the fact that the tall windows haven’t been boarded. Their bare casements are fringed with the gauzy remains of curtains. Snow starts to flutter and gust, flutter and gust, in through the windows as if hundreds of moths have been lured in by the promise of lit bulbs to bash themselves against.

It’s dark outside, but almost morning, and some of the early risers are waking. Pressia’s stayed up all night again. Sometimes she gets so lost in her work that she loses track of time. She’s holding a mechanical arm she’s just made from scraps that El Capitan brings her—silver pincers, a ball-bearing elbow, old electrical cord to cinch it, and leather straps that have been measured to cuff the amputee’s thin biceps. He’s a nine-year-old with all five fingers fused together, almost webbed. She whispers the boy’s name hoarsely. “Perlo! Are you here?”

She makes her way through the survivors, who shift and mutter. She hears a sharp, mewling hiss. “Hush it!” a woman says. Pressia sees something writhe beneath the woman’s coat and then the silky black head of a cat appears at the side of her neck. A baby cries out. Someone curses. A song rises up from a man’s throat, a lullaby…The ghostly girls, the ghastly girls, the ghostly girls. Who can save them from this world? From this world? The river’s wide, the current curls, the current calls, the current curls…The baby goes quiet. Music still works, music calms people. We’re wretches but we’re still capable of this—songs rising up inside us. She’d like the people of the Dome to know this. We’re vicious, yes, but also capable of shocking tenderness, kindness, beauty. We’re human, flawed, but still good, right?

“Perlo?” she tries again, cradling the prosthetic arm to her chest. Sometimes in crowds like this she now looks for her father—even though she doesn’t remember his face. Before Pressia’s mother died, she showed Pressia the pulsing tattoos on her chest—one of which belonged to Pressia’s father, proof that he’s survived the Detonations. Of course, he isn’t here. He probably isn’t even on this continent—or what’s left of it. But she can’t help searching the faces of survivors for someone who looks a little like her—almond-shaped eyes, black shiny hair. She can’t stop from searching, no matter how irrational it is to believe she might one day find him.

She’s made it all the way across the lobby and comes to a wall plastered with posters. Instead of the black claw, which once struck fear in survivors, this is a poster of El Capitan’s face—stern and tough-jawed. She looks down the row of posters, his eyes all lined up, his brother Helmud a small lump behind El Capitan’s back. Above his head, it reads, ABLE AND STRONG? JOIN UP. SOLIDARITY WILL SAVE US. El Capitan made that up and he’s proud of it. At the bottom, fine print promises an end to Death Sprees—the teams of OSR soldiers assigned to cull the weak, collect their dead in an enemy’s field—and mandatory conscription at sixteen. For those who volunteer, El Capitan promises Food without Fear. Fear of what? OSR has a dark history. People were captured and hauled in, untaught how to read, used as live targets…

All of that is over. The posters have worked. There are more recruits now than ever. They wander up from the city, ragged and hungry, burned and fused. Sometimes, they come as families. He’s told Pressia that he’s got to start sending some back. “This isn’t a welfare state. I’m trying to build an army here.” But so far, she’s always talked him into letting them stay.

“Perlo!” she whispers, walking along the wall, letting her hand slide over the rippled edges of the posters. Where is he? The curtains kick into the room. The snow is drawn in as if the large room were drawing in a deep breath.

One family has propped a blanket on a stick, creating a little tent to block the wind. She used to make little tents in the back of the burned-out barbershop when she was little, with a chair and her grandfather’s cane to prop a sheet, playing house with her good friend, Fandra. Her grandfather called them pup tents, and she and Fandra would bark like puppies. He’d laugh so hard the fan in his throat would spin wildly. She feels a pang of loss—for her grandfather and Fandra, who are both dead, and her childhood, which is dead too.

Outside the windows, guards keep watch at fifty-foot intervals surrounding OSR’s headquarters because Special Forces, released by the Dome, are multiplying. A few weeks ago, they were spotted bounding through the woods—their hulking figures bulked with animal muscle, their skin covered in something synthetic and camouflaged. They’re agile, nearly silent, incredibly fast and strong, and well armed; their weapons are embedded in their bodies. They dart over the Rubble Fields, sprint among trees, race down alleys—quiet and stealthy, making routine sweeps of the city. They want Partridge—Pressia’s half brother—most of all. Partridge is being protected by the mothers, along with Lyda—who is Pure, like Partridge, and was sent out of the Dome as a pawn—and Illia, who was married to the top leader of the OSR, her twisted husband, whom she killed. They get bits of information from sketchy reports sent in from OSR soldiers, who all deeply fear the mothers. One report noted that the mothers are teaching Lyda to fight. She’s just a girl from the Dome with no preparation for the ashen wilds, much less life with the mothers, who can be loving and loyal but also barbaric. How is she doing? Another report mentioned that Illia wasn’t holding up. She’d been protected in the farmhouse all these years, and now her lungs are struggling with the onslaught of swirling ash.

Everyone who was there at the end of Pressia’s mother’s life has to be careful. They’re the ones who know the truth about Willux and the Dome, and perhaps they have something that Willux is still after—the vials. Bradwell and El Capitan stripped as much as they could from her mother’s bunker after she was gone. Partridge has the vials now, and hopefully he’s keeping them safe. They would mean a lot to Willux—with these vials and another ingredient and the formula of how to put them together, he could save his own life. Her mother’s vials are potent, yes, but out here, they’re too dangerous and unpredictable to be of use. They’re souvenirs.

How long can the mothers keep Partridge hidden? Long enough for Partridge’s father to die? This is the great hope—that Ellery Willux will die soon, and Partridge can take over from within the Dome itself. Sometimes Pressia feels like they’re all held in a state of waiting, knowing that something is bound to give, and only then will the future take shape.

Freedle flutters in the pocket of her sweater. She slips her hand inside and runs a finger down the robotic cicada’s back. “Shhh,” she whispers. “It’s okay.” She didn’t want to leave him in her small bedroom, alone. Or was it that she didn’t want to be alone?

“Perlo!” she calls. “Perlo!”

And, finally, she hears the boy. “Here! I’m here!” He scuttles over to her, weaving around survivors. “Did you finish it?”

Pressia kneels. “Let’s see if it fits.” She tucks the leather cuff around his upper arm, tightens it into place by the electrical-cord laces. His fused hand can make a tapping motion. She tells him to apply pressure to a small lever.

Perlo gives it a try. The pincer opens and then closes. “It works.” He opens and closes the pincer quickly again and again.

“It’s not perfect,” she says, “but it’ll help, I think.”

“Thank you!” He says it so loudly that he gets hushed by someone on the ground nearby. “Maybe you can make something for yourself,” he whispers, looking at the doll head. “I mean, maybe there’s something…”

She tilts the doll so its eyes blink—one is slightly gummed with ash and so it clicks more slowly, out of sync with the other. “I don’t think there’s anything that can be done for me,” she says. “But I get by.”

The boy’s mother whisper-calls for him. He whips around, raising the arm in the air triumphantly, and he darts off to show her.

And then there’s a far-off gunshot, its rippling report. Pressia crouches instinctively and reaches into her pocket to protect Freedle. She lifts him and holds him to her chest. Perlo’s mother pulls her son in close. Pressia knows it was probably an OSR soldier taking aim at shifting shadows. Errant gunshots aren’t unusual. But that doesn’t stop her chest from tightening around her heart. It’s Perlo and his mother and a gunshot—the mix of it all—and she remembers the weight of the gun in her arms, lifting the gun, taking aim, firing. Even now her ears ring and she sees the bloody mist rising. It fills her vision. Red blooms before her eyes like the bursting flowers that shoot up in the Rubble Fields. She pulled the trigger, but now she can’t remember if it was the right thing to do. She can’t get it straight in her head. Her mother’s dead. Dead.

She walks quickly, sticking to the edges of the lobby, the posters stretching on and on. She cups Freedle gently. When she comes to a window, she looks out, tentatively.

Wind. Snow. The clouds like clods of ash scuttling across the sky, she can see one bright star—a rarity—and below it, the edge of the woods, the brittle trees huddled and stooped. She can make out the soldiers’ uniforms and the occasional glint of a gun, the thin veils of their breath rising in the cold on the sloping hill. She sees her mother’s face lying on the forest floor and then it’s obliterated. Gone.

Beyond the soldiers, her eyes stutter through the trees. Is something out there—something that wants in? She imagines Special Forces hunkered down in the snow. Do they even need sleep? Are they, in part, cold-blooded, their skins covered in thin scrims of ice? It’s quiet, eerily so, but still there’s a certain coiled energy. It snowed three days ago—a fine dusting at first, it turned heavy—and now the lawn is iced, dark and glassy, in three inches or more and snow is still flitting down.

She feels someone grab hold of her elbow. She turns. It’s Bradwell, the double scars running up his cheek, his dark lashes, his full lips chapped by the cold. She looks at his hand, all ruddy and rough. His broad knuckles are scarred and beautiful. How can knuckles be beautiful? Pressia wonders. It’s like Bradwell invented them.

But it’s not like that between them anymore.

“Did you hear me calling you?” he says.

She feels like he’s talking to her from underwater. Once, while the farmhouse burned, she had the courage to make him promise to find a home for them, but that was only because she didn’t actually believe the moment would last. “What is it?”

“Are you okay? You look dazed.”

“I just had to get an arm to a boy, and there was a gunshot. But it was nothing.” She wouldn’t admit to seeing bright red bursting before her eyes any more than to her fear of falling in love with him. This is one thing Pressia knows is true: Everyone she’s ever loved has died. In light of that fact, how could she ever love Bradwell? She looks at him now and the words drum in her head: Don’t love him. Don’t love him.

“Have you been up all night?” he asks.

“Yes.” She notices his hair is standing up messily on his head. They both have the ability to disappear for days. Bradwell gets devoured by his obsession with the six Black Boxes that tunneled up from the char and rubble of the farmhouse and holes up for days on end in the old morgue, where he now lives in the headquarters’ basement. Pressia gets wrapped up in making the prosthetics. Bradwell is still bent on understanding the past, while she has devoted herself to helping people here and now. “Have you been up all night too?”

“Um, yes. I guess so. It’s morning?”

“Just about.”

“Yeah, then I was. I had a breakthrough with one of the Black Boxes. One of them bit me.”

“Bit you?” Freedle flits nervously in her hand.

He shows her a small puncture wound on his thumb. “Not hard. Maybe just a warning. It likes me now, I think. It started following me around the morgue like a pet dog.” She starts walking down the hall, passing more of El Capitan’s recruitment posters, and Bradwell follows. “I’ve taken them all apart, put ’em back together. And they contain information about the past—as far as I can tell—but they aren’t wired to transmit. They aren’t spies for the Dome or anything like that, which I had to rule out. If they ever had those abilities, they’ve been lost.” Bradwell is on a tear, but Pressia isn’t interested in the Black Boxes. She’s tired of Bradwell’s desire to prove his parents’ Dome conspiracies right, his version of the truth, Shadow History, all of that. “And this one, I can’t explain it—this one is different. It’s like it knows me.”

“What did you do to make it bite you?”

“I was talking.”

“About what?”

“I don’t think you want to know.”

She stops and looks at him. He shoves his hands in his pockets. The birds in his back flutter their wings, agitated. “Of course I want to know. It’s how you unlocked the box, right? It’s important.”

He takes a deep breath and holds it for a moment. He looks at the floor and shrugs. “Okay, then,” he says, “I was rambling about you.”

She and Bradwell have never talked about what happened at the farmhouse. She remembers the way he held her, the feel of his lips on hers. But this kind of love can’t survive. Love’s a luxury. He looks at her now, his head bowed, his eyes locked on hers. She feels heat drill through her body. Don’t love him. She can’t even look at him. “Oh,” she says. “I see.”

“Nope, you don’t see. Not yet. Come with me.” He leads her down another hallway and then turns. And there, sitting by the door, waiting patiently, is a Black Box. It’s about the size of a small dog, actually—the kind her grandfather used to call a terrier, the kind that likes to kill rats.

“I told him to stay and he stayed,” Bradwell says. “This is Fignan.”

Freedle noses up from her palm to see for himself. “Does he know how to sit and shake hands?” Pressia asks.

“I think he knows a hell of a lot more than that.”

Partridge

The root cellar smells like pooled rain water and mildew. Bright red mold spores dot the walls and dirt floor. The walls are lined with the mothers’ jars of strange vegetables pickling in vinegar. Mother Hestra, heavily armed, paces overhead. Each of her footsteps reminds him he’s locked underground. Sometimes, he feels like her footsteps are heartbeats and he’s trapped in the ribs of some enormous Beast.

He hasn’t seen Lyda in six days. Time is hard to measure while he’s alone and bent over the maps of the Dome he’s been making, with only a crack in the cellar door to measure the light of day occasionally interrupted by the skimpy meals the mothers deliver—pale broths, clods of white roots, and occasionally a bite-size cube of meat.

He tells himself that aboveground is no better—the wasted detritus of suburbia. But, by God, he feels trapped, and worse than the feeling of being trapped is the boredom. The mothers gave him an old lamp so he has enough light to work by, and they’ve supplied large sheets of paper, pencils, and plywood that he’s set on the floor and uses as a hard-top desk. He’s making maps, trying to recall all the details of the blueprints that he memorized to get out of the Dome, trying to get everything down as quickly as possible. But hour after hour, minute after minute, footstep overhead after footstep…the boredom becomes blinding.

The truth is he’s forced to rely on the mothers’ protection at least until he decides on a plan. Part of him wants to wait until his father dies. His father is weakening. Decades of brain enhancements have caused a palsy and skin deterioration. Partridge’s mother told him these were the signs of Rapid Cell Degeneration. Soon, his father’s body will shut down, which might be the perfect time to return. The Dome would likely respect Partridge as his father’s legacy. His father has ruled like a monarch, after all.

But the other part of him would like to take down his father while he’s alive, defeat him for the right reasons. Don’t the people of the Dome deserve to know the truth about what his father did? If he can get that truth to them and explain that there’s another way to live—one in which they aren’t just sheep following his father’s orders, one in which they don’t see the survivors as evil wretches who deserve their fate—they’d choose it over his father’s reign. Partridge is sure of it.

He’s got to find time with Lyda to make a plan. It feels inevitable that they’ll go back, together.

Meanwhile, he focuses on finishing the maps, pushing through the solitary confinement, the blunt force of boredom, mold and spores, rationed food, and, stripped of all weapons, the awful feeling of needing the mothers, who treat him like a child and, at the same time, a dangerous criminal. They still consider him the enemy, especially because he comes from the Dome; he’s a Death—a man, but, worse, a man from the Dome—and can’t be trusted.

The mothers are interested in the maps, which is why they’ve given him supplies, but Partridge wants to get them to El Capitan. It’s the one gift Partridge has to give. They may never be of use; what are the chances El Capitan will ever form a viable army capable of taking down the Dome? Still, it’s something Partridge can contribute. As he works on the maps, he lets his mind drum over all the things his mother told him before she died. He’s written down every word he could recall; all of it feels embedded with information, coded.

He puts down his pencil, opens and closes his fist. His hand’s cramping, even his partially chopped-off pinky, which has healed to a shiny red nub. He rubs his fingers together, feeling the slickness of the waxy serum that the mothers recently had him bathe in, as preparation for an upcoming journey. The serum, extracted from a camphor tree and beeswax, is supposed to lock in his scent and mask it. His skin is stiff and shiny. There are reports that Special Forces have an excellent sense of smell, as do some of the other Beasts and Dusts. The mothers never let Partridge and Lyda stay in one place too long. They’re protective, yes, but also Mother Hestra told Partridge that they can’t risk Special Forces closing in on Partridge, putting them all in danger. Nomadic living is best.

He wonders if Lyda has been bathed in the serum too. He’s always afraid that, one day, she won’t come on the journey to the next place. So far she always has. He tries to imagine the feel of her skin encased in this waxiness.

Sitting on the dirt floor beside him is his mother’s metal music box, first found in her drawer in the Personal Loss Archives; Bradwell charred it in the butcher-shop basement. But he made sure that Partridge got it back. Bradwell’s more sentimental than Partridge thought, and when it comes to things your parents have left behind, Bradwell has a soft spot. Partridge has rubbed the soot from the music box, but the gears are still blackened. Because all its parts are metal it still works, though it’s off-key and a little muted now. It’s the only thing the mothers let him keep—maybe because they’re mothers themselves. He lifts the box, winds it, lets it play, the notes tinking in the close damp air. He misses his mother. He missed her for so much of his childhood, he’s gotten good at missing her. Maybe it’s why he’s so good at missing Lyda. Years of practice.

When the notes die out, he looks at this most recent map, a cross section of the Dome’s three upper tiers—Upper One, Upper Two, and Upper Three—and three subfloors called Sub One, Sub Two, and Sub Three, which include a section for the massive power generators. The ground floor is called Zero—home to the academy, where he spent most of his time.

He misses the academy with relentless longing. He shouldn’t want to be back in his dorm room, hanging out with Hastings, begging Arvin Weed for his notes, hoping to avoid the herd—a group of boys who pretty much hate him—but he does. He even misses his classes. He thinks of Glassings, his history teacher, in that moment he pulled him aside in the hallway outside the dance. Partridge was just about to steal the knife, so, in retrospect, it was the moment when he could have turned back, continued on with his familiar life.

That’s not how it went. Somehow he ended up here, powerless.

The irony is he has the vials, his mother’s life’s work—the vials are powerful. His father murdered for them—Pressia’s adoptive grandfather, as well as his father’s own oldest son and the woman his father supposedly loved, Partridge’s mother.

The vials remind him of what his mother wanted him to become—a revolutionary, a leader.

Partridge walks to the mothers’ pickled jars and picks one up, third from the corner. Under it there’s a narrow, deep hole, and a few beetles skitter away. He fits his hands down in and lifts a tightly wrapped bundle, lightly caked in moist dirt. He carries the bundle to his cot and unwraps his mother’s vials, four of them attached to syringes with hard plastic covers over the needles. After the farmhouse burned, Bradwell and El Capitan took them from his mother’s bunker, along with anything else that might be of use—computers, radios, medicine, supplies, guns, ammunition. Afterward, it seemed smart to split the group in two—El Capitan, Helmud, Bradwell, and Pressia went to headquarters; Lyda, Partridge, and Illia went with the mothers because they have the greatest ability to keep Partridge hidden and heavily guarded. If one group was found by Special Forces, at least the others could carry on. Bradwell and El Capitan took the bulk of his mother’s stuff, but Partridge hid the vials under his jacket.

He checks each vial. They’re cool to the touch. Partridge’s mother took Partri

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...