- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

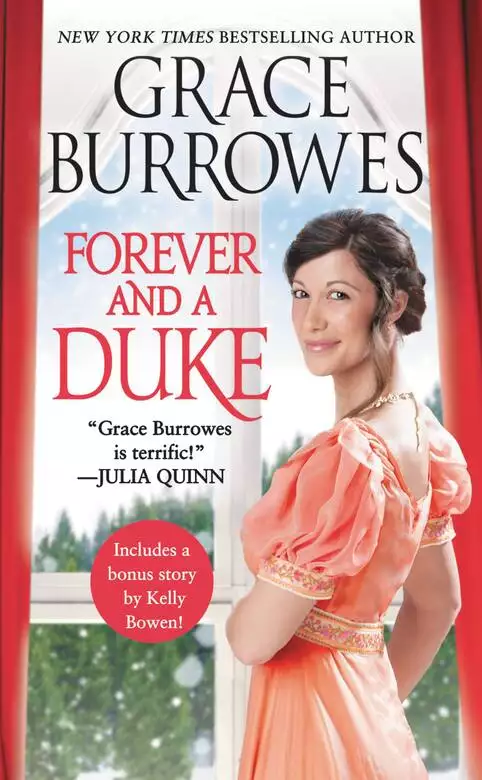

A duke meets his match in the last place he'd ever expect in this charming Regency romance.

Wrexham, Duke of Elsmore, is overrun by family obligations. With three sisters to escort about Town, a legion of cousins to look after, and aunties who insist he dance with every eligible young woman, he barely has time to manage his dukedom. When he finally carves out a moment to evaluate his family's finances, he learns that he — and his sisters — are on the verge of social catastrophe.

Eleanora Hatfield has an uncanny knack for numbers, but she knows from experience that dealing with the peerage can only lead to problems. Though she wants nothing to do with any titled gentleman, she reluctantly agrees to help when Rex seeks aid from her employer. What starts out as an unwanted assignment soon leads to forbidden kisses and impossible longings. But with scandal haunting Ellie's past and looming in Rex's future, how can true love lead to anything but heartbreak?

Includes the bonus story "The Lady in Red" by Kelly Bowen!

Release date: November 26, 2019

Publisher: Grand Central Publishing

Print pages: 464

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Forever and a Duke

Grace Burrowes

“Eleanora Hatfield is like the fellow who extracts a bad tooth,” Joshua Penrose said as he set a brisk pace down the walkway. “Your very survival means you allow him to inflict his special brand of agony, though you dread each encounter.”

“Not a flattering analogy to apply to any female, Penrose.” Wrexham, Duke of Elsmore, paused to examine a flower girl’s offerings at the corner. He and Penrose weren’t due at the bank for nearly a quarter of an hour, after all.

“How are you today, Miss Marybeth?”

She had the usual offerings—carnations for the lapel, tussy-mussies to take on a courting call, nose-gays of sweet pea and lavender, small sprays of muguet-des-bois.

“I’m in good health, Your Grace. And you?”

He chose a little arrangement of violets and mouget-de-bois. “I’m preparing to prostrate myself before that great institution known as Wentworth and Penrose. Very imposing financial organization. I must look my best. What shall we choose for Mr. Penrose?”

Penrose bore Marybeth’s inspection with an impatient twirl of his gold-handled walking stick. Marybeth considered him with an odd gravity for a mere girl, then passed over a bright red carnation arranged as a boutonniere.

“The gentleman would disdain to wear more than one simple flower. He hasn’t your ability to wear posies, Your Grace.”

“What a wise young lady you are.”

She smiled, which also made her a pretty young lady. Rex would ask his cook how soon they could hire a new scullery maid, for a London street corner wasn’t safe for the poor and lovely.

“Go on with ye, Your Grace. I’ve other custom to see to.”

That was the point. Rex enjoyed cutting a dash, but a duke’s choice of flower stall could mean the difference between the flower seller’s family eating meat that week or going without.

“And well you should have other custom, when your inventory is so impressive.” He paid a little generously, and would have sauntered on down the street, except that Penrose was trying ineffectually to affix his carnation to his lapel.

“Let me,” Rex said, taking the flower in one hand and the pin in the other. This necessitated holding his own boutonniere with his teeth.

Penrose’s expression had For God’s sake, Elsmore written all over it, poor fellow.

“You’ve been working with Walden for too long,” Rex said, stepping back. “A little color in a gentleman’s daytime attire preserves him from utter forgettable-ness. I notice your partner always has flowers on his desk when I call upon him at the bank.”

A detail, but telling. Quinn Wentworth, Duke of Walden, had been raised in the slums and was known to pinch a penny until it took a solemn oath never to be spent again. And yet, the man paid good coin for the lilies of the field.

“Walden wants the bank’s customers to feel comfortable,” Penrose said. “About Mrs. Hatfield.”

“The bringer of agony.” Rex tipped his hat to a pair of dowagers, and because they smiled at him, he also tipped his hat to the pug one of the ladies held. This occasioned giggling from two beldames who probably hadn’t giggled in public for decades.

“As long as Mrs. Hatfield is competent to find the errors in my books,” Rex went on, “and she can do so without alerting the London Gazette, I will consider myself eternally in her debt.”

Perhaps he could make the fearsome Mrs. Hatfield giggle or at least smile. The day—and the night—went ever so much more smoothly when the ladies were smiling.

Penrose tried to walk more quickly; Rex refused to oblige him. They were early, the autumn weather was gloriously temperate for the time of year—a false summer that could not last—and what awaited Rex at the bank was hardly cause for eagerness.

“Mrs. Hatfield,” Penrose said, “is one of those annoying people who can glance at an entire page of figures and spot where somebody read a three as a five. Her acumen is unnerving, and she doesn’t understand how unusual she is.”

Penrose was a lean, tall blond who did justice to exquisitely tailored morning attire, especially now that he’d deigned to adorn himself with a lowly carnation. His origins were vague, but he looked every inch the London nabob. Rex knew Penrose’s partner better than he knew Penrose, but he trusted both men.

Under the circumstances, Rex had no choice but to trust them.

“Isn’t it in the nature of an eccentric,” he said, “to believe themselves the pattern card of normality? One of my aunts collects shoes. She goes on and on about them, and no matter how often the subject is changed, she brings the conversation back to shoes as if no other topic merits discussion.”

“You dare not refer to our Mrs. Hatfield as eccentric,” Penrose said, looking about as if checking for eavesdroppers. “She will reciprocate with her own opinion regarding you, the king, the Corn Laws, and half the bills pending in Parliament.”

“You are protective of your auditor,” Rex said. “You needn’t be. I respect ability wherever I find it.” Then too, beggars could not be choosers, especially not ducal beggars.

They came to another intersection and Rex flipped the crossing sweeper a coin. “How’s business, Leonidas?”

The boy caught the vale in a grimy paw. “Right stinky, Your Grace, thank you very much.”

“Glad to hear it. Try calling your enterprise odoriferous instead. You’ll sound like a duke.”

“Odor-ripper-us,” Leonidas replied, grinning.

“Almost. Odor-if-or-us.”

“Odoriferous. My enterprise is odoriferous and that means my job stinks. Thankee, Your Grace.”

Penrose made a sound that might have been distress and cut across the street the instant a coach and four had rattled past.

“Enterprise and enterprising were last week’s words,” Rex said. “He likes big words, and I like to cross the street without stepping in horse droppings. A fair exchange.”

That observation spiked Penrose’s guns for about six paces, then, like the stalwart financier he was, he regained his verbal footing, more’s the pity.

“Regarding Mrs. Hatfield,” he said. “What she has, Your Grace, goes beyond ability. She was one of our first customers, because she had known His Grace of Walden previously. His reputation for fair dealing preceded him, which is why, when her statement arrived with a mistake amounting to tuppence, she demanded to see the bank partners. She looked about at the clerks, pointed a finger at one of our most promising lads, and accused him of failing to focus on his duties.”

“Imagine that, a bank ledger failing to hold a fellow’s attention.” Rex knew of no stronger soporific than column after column of figures. He’d inherited the Dorset and Becker Savings and Trust at the age of twenty-one, a singular irony when a man had little aptitude for bookkeeping and inadequate time to tend to his own finances.

“Mrs. Hatfield looked at a dozen young fellows,” Penrose went on, “all dressed about the same, and picked out the one who’d made a minor error. When we went back through his work—at her insistence—he’d made two other mistakes, one for eight pounds. His calculations were usually so accurate that the man assigned to verify them hadn’t paid adequate attention either.”

Penrose had clearly been fascinated with this two-penny drama, while Rex simply wanted to be done with the day’s business. No previous Duke of Elsmore had ever had to bother his handsome head about two pounds, much less tuppence.

Hence, Rex’s present difficulty. “How did Mrs. Hatfield identify the culprit?”

Penrose paused at the foot of the steps that led to his bank’s impressive double doors. “The young man had taken on a second job copying a silk merchant’s daily receipts each evening. His clothing was rumpled from having been slept in. He was pale, his eyes were slightly bloodshot, and he had a wax stain on the cuff of his shirt though the bank uses lamps rather than candles in the counting room. She not only spotted those details immediately, she also connected them to her missing tuppence. The boy was tired and his work grew sloppy as a result.”

“Mrs. Hatfield sounds impressive.” Also like she’d get on well with the aunties. Rex could picture them, a quartet of unrepentant old besoms, cackling like the Fates over tattle and tea.

“Impressive is the right word. I feel it fair to warn you she does not generally hold aristocrats in high regards, sir.”

“Neither do I, Mr. Penrose. Always a pleasure to make the acquaintance of a woman of sound sensibilities. I’m sure we’ll get on famously.”

* * *

“My grandmother, whose good opinion of me ranks among my greatest treasures, pounded a few simple rules into her progeny.” Eleanora Hatfield spoke calmly, as one must when addressing one’s misguided employer. “Foremost among her rules is to never involve myself in the affairs of the peerage. Peers are trouble, and dukes the worst of the lot.”

Quinn Wentworth, who had the great misfortune to be the Duke of Walden, drummed his fingers on the blotter of his massive desk. His nails were clean now, but Ellie had known him when he would have literally dirtied his hands doing any honest work.

“You don’t mind involving yourself weekly with the bank’s wage book, Eleanora Hatfield, and I number among the realm’s peers.”

Ellie wanted to pace and wave her hands, but had learned long ago that women were denied the luxury of speaking emphatically, if they wanted to be taken seriously. Of course, when she spoke moderately, she was also brushed off at least half the time, particularly by her own family.

She remained seated across from the desk, hands folded in her lap. “Correct you are, Your Grace, and look how you thank me for making a single exception to Grandmama’s cardinal rule. You shove me out the door to chase down a missing penny for some fop who cannot be bothered to tally his own estate books.”

“Madam, we are not shoving you out the door.” His Grace adopted the wheedling, now-be-reasonable tone that made Ellie want to shut herself in the bank’s vault. When Walden spoke to her like that, his blue eyes all earnest innocence, her grandmother’s sage advice might as well have been instructions for the care and feeding of spotted unicorns.

“A few weeks,” the duke continued, “a month at most, and you’ll have His Grace of Elsmore’s situation put to rights. You glance at a set of books and see what’s amiss with them. Your powers of divination are legendary. For you to ferret out the problem with Elsmore’s family accounts—”

“Need I remind you, sir, that I am a bank auditor. I will have no truck with a ducal family’s ledgers.”

Walden sat back, a financial king comfortable in his padded leather throne. “You inspect my household books. You do the monthly reconciliations for Lord Stephen and other members of the Wentworth family.”

“You cannot help that you’ve become a duke,” Ellie shot back. “I’ve overlooked that sad development for the past six years, and I’m willing to continue to extend you my tolerance because you are a decent man, you pay honest wages, and your title was none of your doing.”

Her profession of loyalty had apparently sent her into some sort of verbal trap. A slight shift in His Grace’s expression, a hint of a smile in his eyes, foretold her doom.

“Elsmore cannot help his birthright either. Is our own Mrs. Hatfield, defender of balanced ledgers and retriever of lost pennies, really such a snob?”

Not a snob. Sensible. “When did we lose you?” Ellie retorted. “You were one of us, born to scrape out a living as best you could, fated to dread cold and consumption along with most of the rest of England. Now you ask a favor from me on behalf of one of them.”

The duke’s smile died aborning, replaced by the signature Quinn Wentworth glacial dignity.

“You lost me,” he said, “the moment I held my oldest child in my arms. Elizabeth will make her come-out someday, God willing, as will her sisters. Elsmore was the first peer to acknowledge my title, the first to leave his card. His mother and sisters call on my duchess. When my Bitty makes her bow, she’ll have her pick of the bachelors, in part because several years ago, Elsmore opened doors for the Wentworth family.”

That recitation sealed Ellie’s fate.

If His Grace considered himself indebted to the Duke of Elsmore, then Ellie’s job was forfeit should she refuse this assignment. Quinn Wentworth was loyal to his employees, but he was fanatically devoted to family.

A quality to be respected, most of the time. “I love working for Wentworth and Penrose,” Ellie said. “I love the smell of the beeswax polish on the wainscoting, love how sunlight comes through the windows because you insist they always be clean. I love…”

She loved the sense of safety here, of having a worthwhile place and knowing it well. Her family could cheerfully racket from one misadventure to another. Ellie had to have peace, order, and respectability.

“You love how the clerks live in dread of your raised eyebrow,” His Grace said. “Love knowing which messengers favor licorice candy and which prefer peppermint. We’re your family, so on behalf of that family, I ask you to extend a courtesy to another institution. If one bank fails, all banks suffer, and rumors about His Grace’s personal finances would send Dorset and Becker straight into the cesspit.”

He had her there. A bank might start the week solvent and, on the strength of nothing more than club gossip about a single bank director, end the week floundering.

“I don’t want to do this. Why can’t Elsmore’s solicitors manage this task?”

“I didn’t want to be a duke, Eleanora. Elsmore’s solicitors should already have seen any irregularities in the estate books. That they either failed to notice them or declined to mention them means the lawyers can’t be relied on. This project should be your idea of a holiday. Say you’ll do it, and I’ll introduce you to Elsmore.”

Wentworth and Penrose had given Ellie a job when most banks considered women fit only to scrub the floors after hours. There were exceptions of course. Lady Jersey ran Child’s Bank. Her Grace of St. Alban’s managed Coutts, but Ellie was neither a countess nor a duchess. Quinn Wentworth and Joshua Penrose had opened the door to respectability for her, and thus, Ellie would always be in their debt.

“I’ll have a look at Elsmore’s estate books,” she said, “and maintain my duties here. In the evenings, His Grace must make available to me any document I request.”

“Elsmore’s holdings are more complicated than my own, and a few hours of an evening won’t allow you to do justice to the task. I’ll inform Milton that you’ve taken a month’s leave to deal with a family matter.”

That Walden was willing to part with Ellie’s services for a month told her volumes about his sense of indebtedness to Elsmore. All that remained was to be introduced to the mincing fop who’d mucked up simple math relating to bales of wool and boxes of candles.

“Wentworth and Penrose cannot audit itself over the next month,” Ellie said. “Who will mind the books here while I’m gone?”

“You’ll be gone for only a month.”

“Two weeks, during which the tellers will notice that I’m away from my post. They won’t mean to make errors, but every one of them occasionally does. You do too.” About twice a year, which was amazing, considering the sheer volume of calculations His Grace performed. He not only kept his hand in as a bank director, he owned half a dozen properties, and oversaw a few charities as well.

The duke paused halfway to the door. “What do you suggest?”

Ellie got to her feet, because putting off the inevitable was not in her nature. “Did you honestly think to let the books go for even two weeks without a reconciliation? Did you expect me to merely skim a few pages when I returned from this frolic for Elsmore? Haven’t I taught you any better than that?”

“Two weeks isn’t so long,” the duke said. “I’ll keep a close eye on the bank in your absence.”

Ellie marched up to him. “Not good enough. You are the managing director for the institution and you still post entries from the head teller’s ledger to the bible if Mr. Penrose is otherwise occupied. You will have Lord Stephen review the books in my absence. If there’s an error, he’ll find it.”

Lord Stephen was the duke’s younger brother, a genius of protean interests, and a right pain in His Grace’s arse. Ellie rented rooms in one of his lordship’s properties, and while his lordship had a genius’s share of impatience with lesser mortals, Ellie trusted him to review the books.

“By choosing Lord Stephen to hold the reins, you are punishing me for asking a favor of you,” His Grace said, “and yet the work—finding inconsistencies in the books—is your greatest delight in life.”

He always smelled good, of flowers and spices. Ellie hadn’t realized that until Jane, Her Grace of Walden, had listed a pleasant scent among her husband’s many adorable qualities. The notion of anybody adoring a duke…

“My greatest delight in life is looking after the books at my bank, Your Grace. Tidying up after some prancing buffoon with too much money and not enough meaningful work is my idea of a penance.”

His Grace opened the door and gestured for Ellie to precede him. “Come along, then. Elsmore is kicking his heels with Penrose in the conference room. I’ll introduce you to your penance.”

Just like that, the battle was over and lost, and Ellie’s next two weeks taken hostage. “I will start Elsmore’s audit on Monday.”

“Elsmore will be overjoyed to hear it.”

“And well he should be.”

His Grace allowed Ellie to have the last word, which was prudent of him.

Joshua Penrose stood when Ellie entered the conference room, as did another man. Ellie took one look at the stranger and cursed herself for a fool, though Elsmore bowed politely and thanked her for being willing to “lend her assistance.”

She’d been wrong, and she hated being wrong. Elsmore was neither a fop, nor prancing, nor a buffoon, and two weeks in his employ would be the longest fortnight of her life.

* * *

Rex had waited in the Wentworth and Penrose conference room like a brawling schoolboy awaited a headmaster’s judgment, though no schoolyard pugilist had ever enjoyed such luxurious surroundings. The walls were wainscoted in oak and covered with green silk. The floors sported first-quality cream, gold, and green Axminster from wall to wall. The furniture was heavy, well padded, and polished to a gleaming shine.

This might have been any conference room in any bank, except—Rex hadn’t noticed this until he’d been in the room many times—the windows were clean, inside and out, despite being one floor above a busy street. London coal smoke dirtied everything it touched, from laundry to ladies’ gloves to Mayfair mansions.

The result of clean windows, though, was a rare sense of light and freshness within Wentworth and Penrose’s walls. Unlike most commercial establishments—including Dorset and Becker, come to think of it—this bank was maintained to the standards of a wealthy domicile rather than a busy shop. The difference was both subtle and profound.

Cathedrals, unheated and often set apart from major cities, had the same clean, benevolent light.

The Duke of Walden himself held the door for a smallish female who preceded him into the room as if he were her footman rather than a wealthy peer.

Rex liked women—almost all women, which was handy when a fellow was knee-deep in sisters, aunties, and cousins of the feminine persuasion. He would have stood had any female joined the meeting, because manners were the least courtesy the ladies were due.

With this woman, a man would sit about on his lazy backside at his peril. She did not walk, she marched, plain gray skirts swishing like finest silk. Her posture would have done credit to Wellington reviewing the troops before a battle. She wore her dark hair in a ruthlessly tidy bun; a pair of spotless spectacles perched halfway down a slightly aquiline nose.

She had the figure of an opera dancer and the bearing of a thoroughly vexed mother superior.

Rex took in these details—and interesting details they were—as the lady crossed the room and snapped off a shallow curtsey. She declined to offer her hand, as was a woman’s prerogative.

He bowed, and for once refrained from smiling at a female. He had an arsenal of smiles. Friendly, flirtatious, bored, condescending, menacing—that one was not for use with the ladies—but this woman would likely slap him silly for such posturing.

The Duke of Walden dealt with the introductions, and all the while, Mrs. Hatfield studied Rex as if deciding where to take the first bite of him.

“Elsmore at your service, madam. A pleasure to meet you.”

She aimed a glower down that not-exactly-dainty nose. “Likewise, Your Grace.”

“We’ll leave you two some privacy,” Penrose said. “Would not do for Wentworth and Penrose to be privy to the concerns of a rival institution’s director. Your Grace, madam, good day.”

He trundled off to the door, a tutor much relieved to turn his charge back over to the nursery maids. Walden followed him but paused before leaving.

“I’m down the corridor if I’m needed.” He sent Rex an unreadable look, then left, closing the door.

“Which of us do you suppose would be calling upon Walden for aid?” Rex asked. “I don’t quite count His Grace a friend, but I have asked this favor of him, haven’t I?” Rex wasn’t sure anybody considered Walden a friend, and Walden appeared to prefer it that way.

Mrs. Hatfield opened a drawer at the head of the table and withdrew several sheets of paper and a pencil.

“The favor you seek is from me, Your Grace. Applying to my employers was mere courtesy. Shall we begin? I need to know exactly what evidence you have of errors in your bookkeeping, and the sooner we embark on that discussion the sooner you can get back to”—her gaze flicked over him—“whatever it is you do.”

“I’m sure your time is valuable,” Rex said, pulling out a chair for her. “I appreciate that you’re willing to take on this project.”

He more than appreciated it. If his personal books were problematic, whether due to errors, bad accounting procedures, or something else, his own solicitors hadn’t noticed. Rex would explain the situation to them only after he grasped how the inaccuracies had arisen and what to do about them.

Mrs. Hatfield looked at the chair, then at him, her air of annoyance fading into puzzlement. “You need not act the dandy with me, sir. I am entirely capable of managing both my skirts and a chair. One can, if one dresses sensibly.”

Eleanora Hatfield did everything sensibly. Rex knew this from the tiny dash of lace at her collar, from the small, plain watch pinned to her left sleeve—an odd but practical location—and from the ink stain on her right thumb.

She was painfully sensible, while he was…painfully worried about his wretched, blasted, bedamned family finances.

“Holding a chair for a lady is not acting the dandy, madam, but rather, being a gentleman. If the fellows at this institution have inured you to discourtesy, shame upon them, for I am unwilling to commit the same transgression.” This skirmish over a chair mattered. Rex needed her help, but he would not be treated like a pestilence when he’d committed no wrong.

Her brows drew down, and fine dark brows they were too. Nicely arched, a little heavier than was fashionable. As she rustled closer, he considered that she wasn’t so much annoyed with him as she was flustered.

“Does nobody hold your chair, Mrs. Hatfield? Mr. Hatfield has much to answer for.”

She sat as regally as a cat settling onto a velvet cushion, tidied the blank paper into a stack, and took up the pencil. “Mr. Hatfield is none of your concern, Your Grace. Tell me about your situation and spare no details. My discretion is absolute, and I gather the situation is becoming urgent.”

The situation, in Rex’s opinion, had passed urgent some time ago. If his instincts were to be trusted, and they generally were, the situation now qualified as dire.

Chapter Two

Rex began a recitation of the family’s history, which as far as titleholders were concerned, went back for three dreary centuries. The previous Elsmore peers had had a knack for coming down on the right side of political dramas, which had started them off with an earldom, and then seen them elevated to ducal honors. By then, the family had founded the Dorset and Becker Savings and Trust, though the Dukes of Elsmore had known better than to keep exclusive control of the institution in their own hands.

Other venerable families had shares in the bank, allowing Rex’s ancestors to retreat to the gentility of directorships and quarterly meetings. Younger sons and cousins involved themselves in the business as employees. Thus the institution remained a family venture, and solved the conundrum of what to do with spares and relations unsuited for the church or the military.

“This arrangement has served us well,” Rex said, “and also served the bank well.”

Mrs. Hatfield scratched away with her pencil for a moment. “If your books aren’t balancing, then some aspect of the dukedom is not in good repair. Somewhere in your ledgers, a cross-tally isn’t done, a series of entries is not verified. Bookkeeping is both an art and a science, and yours has fallen into disrepair.”

She spoke gently, as if diagnosing him with a serious illness.

“The problem is doubtless minor,” Rex replied, “but over time, small amounts can add up. The Dukes of Elsmore have always had a sterling reputation, as has any financial institution we take an interest in. I am determined to uphold that tradition.”

An auditor ought not to have such pretty eyes. Mrs. Hatfield peered over her spectacles, looking like a solemn little owl, except that an owl’s eyes didn’t slant like a cat’s, or shade toward a velvety chocolate. Nor did an owl have a capacity to appear concerned over a few missing quid.

“How did you first notice something amiss, Your Grace?”

“A few details that literally didn’t add up.” And a persistent suspicion that a prudent peer would spend less time waltzing and more time with an abacus. “A tally here, a shortfall there. Must we trouble ourselves over those specifics now?”

Mrs. Hatfield put down her pencil. She checked her watch and compared the time with that told by a great monstrosity ticking away on the mantel. Rex had the sense she was choosing her words, or perhaps counting to ten.

“The word auditor comes from the Latin audire,” she said, “meaning to hear. An auditor listens, Your Grace. In former times, we listened to the accounts read out while we kept tallies in our heads. Now we not only pay attention to the books, we also attend to what happens around those books. Anybody can make a mistake in calculations or transcription. You can see a seven where I see a one. But if what’s occurring is something other than random errors, then I must discern the pattern, and that means I need all the information you have.”

She spoke so earnestly, as if instructing a slow scholar who very, very much needed passing marks.

Rex rose, having tolerated as much inactivity as he could. “You want to know how much I lost at the club last night? What I spent at the haberdasher’s? What baubles I purchased for my current chère amie?”

“Yes, though I doubt you have a mistress in keeping at present.”

A frisson of unease had Rex pretending to examine a sketch of a small girl with a large dog. In a few strokes, the artist had caught the dog’s protectiveness and the child’s trust, also her resemblance to the current Duchess of Walden.

“Mrs. Hatfield, you cannot possibly divine that I’m without a current attachment merely by looking at me.”

“Of course not,” she said, using a penknife to sharpen her pencil point. “I merely read the newspaper. You are escorting only the most eligible of the blue-blooded young ladies these days, but not singling any woman out for special attention. Your set considers it good form to approach marriage without other entanglements, and you are of an age to take a wife. You have no direct heir, no younger brother even. Hence, my conclusion. Now, might we resume our discussion of your books?”

Rex’s social life apparently did not interest her beyond what was reported in the tattlers, but then, the vast, ceaseless whirl of his entertainments seldom interested him. He wandered back to the table and sent the lady a questioning glance.

“Mind if I sit?”

“Your Grace, if you insist on silly rituals we will accomplish little. You must treat me as if I were a chambermaid or a footman, an employee, though one who labors with her mind rather than her hands. No more of your chair-holding, bobbing about, or pretending you need my permission to sit.”

Her handwriting was painfully neat, her attire painfully plain, and yet simple manners flustered her.

Rex remained by the chair to her left. “As a boy, I slurped up proper deportment with my morning porridge, and as a peer, I hold myself out as an example of British manhood at its most refined, at least when a lady is present. With you, I must tend to the silly rituals or I will lose my good standing in the Decorous Dukes club.”

That salvo earned hi

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...