- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

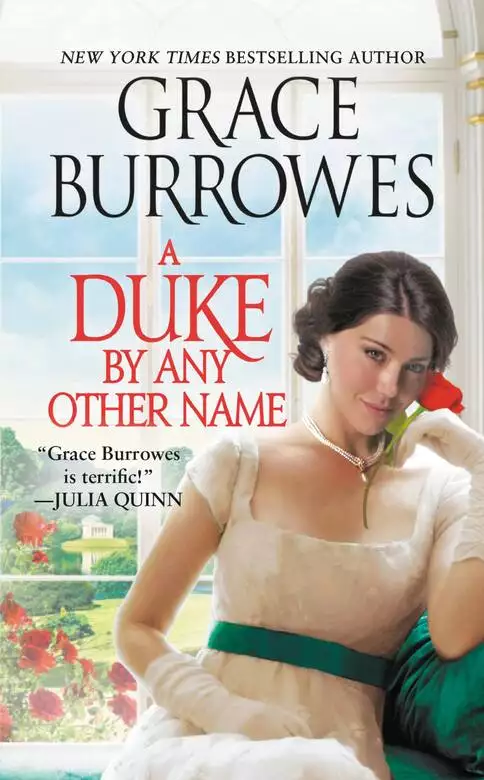

With her trademark wit, New York Times best-selling author Grace Burrowes delivers a charming Regency romance featuring a duke who excels at brooding in solitude and the lady who refuses to leave him in peace.

Nathaniel, duke of Rothhaven, lives in seclusion, leaving his property only to gallop his demon-black steed across the moors by moonlight. Exasperated mamas invoke his name to frighten small children, though Nathaniel is truly a decent man —maybe too decent for his own good. That's precisely why he must turn away the beguiling woman demanding his help.

Lady Althea Wentworth has little patience for dukes, reclusive or otherwise, but she needs Rothhaven's backing to gain entrance into polite society. She's asked him nicely, she's called on him politely, all to no avail —until her prize hogs just happen to plunder the ducal orchard. He longs for privacy. She's vowed to never endure another ball as a wallflower. Yet as the two grow closer, it soon becomes clear they might both be pretending to be something they're not.

Release date: April 28, 2020

Publisher: Forever

Print pages: 385

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Duke by Any Other Name

Grace Burrowes

“Lady Althea Wentworth is, without doubt, the most vexatious, bothersome, pestilential female I have ever had the misfortune to encounter.” The hog sniffing at Nathaniel Rothmere’s boots prevented him from pacing, though the moment called for both pacing and profanity.

The sow was a mere four hundred pounds, a sylph compared to the rest of the herd rooting about in Nathaniel’s orchard; nonetheless, when she flopped to the grass, the ground shook.

“Have you, sir?” Everett Treegum asked with characteristic delicacy. “Encountered the lady, that is?”

“No.” Nor do I wish to.

Another swine, this one on the scale of a seventy-four-gun ship of the line, tucked in beside her herd-mate, and several others followed.

“They seem quite happy here,” Treegum observed. “Perhaps we ought simply to keep them.”

“Then Lady Althea will have an excuse to come around again, banging on the door, cutting up my peace, and disturbing the tranquility of my estate.”

Two more sows chose grassy napping places. Their march across the pastures had apparently tired them out, which was just too damned bad.

“Is it time for a Stinging Rebuke, sir?” Treegum asked, as a particularly grand specimen rubbed against him and nearly knocked the old fellow off his feet. Treegum was the Rothhaven estate steward. Swineherding was not among his many skills.

“I’ve already sent Lady Althea two Stinging Rebukes,” Nathaniel replied. “She probably has them displayed over her mantel like letters of marque and reprisal.” Nathaniel shoved at the hog milling before him, but he might as well have shoved at one of the boulders dotting his fields. “Her ladyship apparently longs to boast that she’s made the acquaintance of the master of Rothhaven Hall. I will gratify her wish, in the spirit of true gentlemanly consideration.”

“Mind you don’t give her a fright,” Treegum muttered, wading around the reclining swine to accompany Nathaniel to the gate. “We can’t have you responsible for any more swoons.”

“Yes, we can. If enough ladies swoon at the mere sight of me, then I will continue to enjoy the privacy due the neighborhood eccentric. I should have Granny Dewar curse me on market day. I’ll gallop past the village just as some foul weather moves in, and she can consign me to the devil.”

Treegum opened the gate, setting off a squeak loud enough to rouse the napping hogs. “Granny will want a fair bit of coin for a public curse, sir.”

“She’s partial to our elderberry cordial.” Nathaniel vaulted a crumbling length of wall one-handed. “Maybe we should leave the gate open.” The entire herd had settled on the grass and damned if the largest of the lot—a vast expanse of pink pork—didn’t appear to smile at him.

“They won’t find their way home, sir. Pigs like to wander, and sows that size go where they please.”

Running pigs through an orchard was an old Yorkshire custom, one usually reserved for autumn rather than the brisk, sunny days of early spring. The hogs consumed the dropped fruit, fertilized the soil, and with their rooting, helped the ground absorb water for the next growing season.

“Perhaps I should saddle up that fine beast on the end,” Nathaniel said, considering a quarter ton of livestock where livestock ought not to be. “Give the village something truly worth gossiping about.”

Treegum closed and latched the gate. “Hard to steer, though, sir, and you do so pride yourself on being an intimidating sort of eccentric.”

“Apparently not intimidating enough. Tell the kitchen I’ll be late for supper, and be sure the hogs of hell have a good supply of water. They will be thirsty after coming such a distance.”

Treegum drifted in the direction of the home farm, while Nathaniel turned for the stables. He preferred to serve as his own groom, and Elgin, the stablemaster, having been on nodding terms with the biblical patriarchs, did not object. He did, however, supervise Nathaniel, as he’d been doing for nearly a quarter century. The other stableboys referred to their supervisor as Elfin, and in all the time Nathaniel had known him, Elgin’s looks had remained true to that description.

“Fine day for a gallop,” Elgin remarked. “Please do avoid the field nearest the river, sir. Too damned boggy yet.”

“I’m paying a call. Wouldn’t do to arrive at her ladyship’s door with mud-spattered boots.”

Elgin took his pipe from between his teeth. “A social call?”

Nathaniel led Loki from his stall. “Shocking, I know.”

“A social call on a fe-male?”

Loki shied and snorted at nothing, then propped on his back legs and generally comported himself like a clodpate.

“Are you quite finished?” Nathaniel inquired of his horse when the idiot equine had nearly banged his head on the rafters.

“Spring is in the air,” Elgin said, clipping Loki’s halter to the crossties and passing Nathaniel a soft brush. “Which ladyship is to have the pleasure of your company?”

“My company will be no pleasure whatsoever.” Nathaniel started on the gelding’s neck, which occasioned wiggling of horsey lips. “I am to call upon Lady Althea Wentworth, our neighbor to the immediate south. Her swine are idling in our orchard, and I have every confidence she had them driven there in the dark of night precisely to annoy me. While I commend her ingenuity—grudgingly, of course—I cannot continue to humor her.”

Loki was five years old, and at more than seventeen hands, he looked like a mature horse, bristling with muscle and energy. He was a typical adolescent, though, both full of his own consequence and lacking in common sense. Robbie had made Nathaniel a gift of him, claiming that even an eccentric duke needed some entertainment.

Nathaniel hadn’t had the heart to refuse his brother, given the effort Robbie must have expended to procure the horse.

“And you are entertaining,” Nathaniel murmured, pausing to scratch Loki’s belly.

“Lady Althea has pots of money,” Elgin observed. “She put that house of hers to rights and made a proper job of it too. She’s a handsome woman, according to the lads at the Whistling Goose.”

“From whom all the best and least factual gossip is to be had.” Nathaniel moved around to Loki’s off side. “When a woman of considerable wealth is described as handsome, we may conclude she is stout, plain, and cursed with a hooked nose.”

“You have a hooked nose,” Elgin said, setting a saddle on the half door to Loki’s stall. “Yon gelding has a hooked nose. I used to have a hooked nose until it got broke a time or three. What’s wrong with a hooked nose?”

“Loki and I have aquiline noses, if you please.”

Loki also had a temper. He objected to the saddle pad being placed on his back, then he objected to the saddle being placed atop the pad. He objected strenuously to the girth—the horse was nothing if not consistent—and he pretended he had no idea exactly where the bit was supposed to end up.

Until Nathaniel produced a lump of sugar. Then the wretched beast all but fastened the bridle on himself.

“Shameless beggar,” Nathaniel said, gently scratching a dark, hairy ear. “But standards must be maintained, mustn’t they?” How often had the previous Duke of Rothhaven intoned that refrain?

“If Lady Althea’s so plain,” Elgin said, “and you aren’t interested in her money, then why must you be the one to inform her that we have her pigs?”

“Ideally, I will inspire her to pack her bags and retreat all the way back to London. Even our formidable Treegum isn’t likely to produce that effect.” Her ladyship did spend some months in the south every year, though she always came north again, like some strange migratory bird helpless to resist Yorkshire winters.

“And if she’s not the retreating kind?”

Nathaniel led his horse out to the mounting block, took up the girth another hole, pulled on his gloves, and swung into the saddle. “Then I will settle for impressing upon her the need to leave me and mine the hell alone.”

“You’re good at that,” Elgin replied, giving the girth a tug. “Maybe too good.”

Loki capered and danced, his shoes making a racket on the cobbles. Then he bolted forward on a great leap and swept down the drive at a pounding gallop. Every schoolboy in the shire knew that His Grace of Rothhaven galloped wherever he went, no matter the hour or the season, because the devil himself was following close behind.

And the schoolboys had the right of it.

Althea heard her guest before she saw him. Rothhaven’s arrival was presaged by a rapid beat of hooves coming not up her drive, but rather, directly across the park that surrounded Lynley Vale manor.

A large horse created that kind of thunder, one disdaining the genteel canter for a hellbent gallop. Althea could see the beast approaching from her parlor window, and her first thought was that only a terrified animal traveled at such speed.

But no. Horse and rider cleared the wall beside the drive in perfect rhythm, swerved onto the verge, and continued right up—good God, they aimed straight for the fountain. Althea could not look away as the black horse drew closer and closer to unforgiving marble and splashing water.

“Mary, Mother of God.”

Another smooth leap—the fountain was five feet high if it was an inch—and a foot-perfect landing, followed by an immediate check of the horse’s speed. The gelding came down to a frisking, capering trot, clearly proud of himself and ready for even greater challenges.

The rider stroked the horse’s neck, and the beast calmed and hung his head, sides heaving. A treat was offered and another pat, before one of Althea’s grooms bestirred himself to take the horse. Rothhaven—for that could only be the Dread Duke himself—paused on the front steps long enough to remove his spurs, whip off his hat, and run a black-gloved hand through hair as dark as hell’s tarpit.

“The rumors are true,” Althea murmured. Rothhaven was built on the proportions of the Vikings of old, but their fair coloring and blue eyes had been denied him. He glanced up, as if he knew Althea would be spying, and she drew back.

His gaze was colder than a Yorkshire night in January, which fit exactly with what Althea had heard of him.

She moved from the window and took the wing chair by the hearth, opening a book chosen for this singular occasion. She had dressed carefully—elegantly but without too much fuss—and styled her hair with similar consideration. Rothhaven gave very few people the chance to make even a first impression on him, a feat Althea admired.

Voices drifted up from the foyer, followed by the tread of boots on the stair. Rothhaven moved lightly for such a grand specimen, and his voice rumbled like distant cannon. A soft tap on the door, then Strensall was announcing Nathaniel, His Grace of Rothhaven. The duke did not have to duck to come through the doorway, but it was a near thing.

Althea set aside her book, rose, and curtsied to a precisely deferential depth and not one inch lower. “Welcome to Lynley Vale, Your Grace. A pleasure to meet you. Strensall, the tea, and don’t spare the trimmings.”

Strensall bolted for the door.

“I do not break bread with mine enemy.” Rothhaven stalked over to Althea and swept her with a glower. “No damned tea.”

His eyes were a startling green, set against swooping dark brows and features as angular as the crags and tors of Yorkshire’s moors. He brought with him the scents of heather and horse, a lovely combination. His cravat remained neatly pinned with a single bar of gleaming gold despite his mad dash across the countryside.

“I will attribute Your Grace’s lack of manners to the peckishness that can follow exertion. A tray, Strensall.”

The duke leaned nearer. “Shall I threaten to curse poor Strensall with nightmares, should he bring a tray?”

“That would be unsporting.” Althea sent her goggling butler a glance, and he scampered off. “You are reputed to have a temper, but then, if folk claimed that my mere passing caused milk to curdle and babies to colic, I’d be a tad testy myself. No one has ever accused you of dishonorable behavior.”

“Nor will they, while you, my lady, have stooped so low as to unleash the hogs of war upon my hapless estate.” He backed away not one inch, and this close Althea caught a more subtle fragrance. Lily of the valley or jasmine. Very faint, elegant, and unexpected, like the moss-green of his eyes.

“You cannot read, perhaps,” he went on, “else you’d grasp that ‘we will not be entertaining for the foreseeable future’ means neither you nor your livestock are welcome at Rothhaven Hall.”

“Hosting a short call from your nearest neighbor would hardly be entertaining,” Althea countered. “Shall we be seated?”

Lynley Vale had come into her possession when the Wentworth family had acquired a ducal title several years past. Althea’s brother Quinn, the present Duke of Walden, had entrusted an estate to each of his three siblings, and Althea had done her best to kit out Lynley Vale as befit a ducal residence. When Quinn visited, he and his duchess seemed comfortable enough amid the portraits, frescoed ceilings, and gilt-framed pier glasses.

Rothhaven was a different sort of duke, one whose presence made pastel carpets and flocked wallpaper appear fussy and overdone. Althea had been so curious about Rothhaven Hall she’d nearly peered through the windows, but Rothhaven had threatened even children with charges of trespassing. A grown woman would get no quarter from a duke who cursed and issued threats on first acquaintance.

“I will not be seated,” he retorted. “Retrieve your damned pigs from my orchard, madam, or I will send them to slaughter before the week is out.”

“Is that where my naughty ladies got off to?” Althea took her wing chair. “They haven’t been on an outing in ages. I suppose the spring air inspired them to seeing the sights. Last autumn they took a notion to inspect the market, and in summer they decided to attend Sunday services. Most of our neighbors find my herd’s social inclinations amusing.”

“I might be amused, were your herd not at the moment rooting through my orchard uninvited. To allow stock of those dimensions to wander is irresponsible, and why a duke’s sister is raising hogs entirely defeats my powers of imagination.”

Because Rothhaven had never been poor and never would be. “Do have a seat, Your Grace. I’m told only the ill-mannered pace the parlor like a house tabby who needs to visit the garden.”

He turned his back to Althea—very rude of him—though he appeared to require a moment to marshal his composure. She counted that a small victory, for she had needed many such moments since acquiring a title, and her composure yet remained as unruly as her sows on a pretty spring day.

Though truth be told, the lady swine had had some encouragement regarding the direction of their latest outing.

Rothhaven turned to face Althea, the fire in his gaze banked to burning disdain. “Will you or will you not retrieve your wayward pigs from my land?”

“I refuse to discuss this with a man who cannot observe the simplest conversational courtesy.” She waved a hand at the opposite wing chair, and when that provoked a drawing up of the magnificent ducal height, she feared His Grace would stalk from the room.

Instead he took the chair, whipping out the tails of his riding jacket like Lucifer arranging his coronation robes.

“Thank you,” Althea said. “When you march about like that, you give a lady a crick in her neck. Your orchard is at least a mile from my home farm.”

“And downwind, more’s the pity. Perhaps you raise pigs to perfume the neighborhood with their scent?”

“No more than you keep horses, sheep, or cows for the same purpose, Your Grace. Or maybe your livestock hides the pervasive odor of brimstone hanging about Rothhaven Hall?”

A muscle twitched in the duke’s jaw.

Althea had been raised by a man who regarded displays of violence as all in a day’s parenting. Her instinct for survival had been honed early and well, and had she found Rothhaven frightening, she would not have been alone with him.

She was considered a spinster; he was a confirmed eccentric. He was intimidating—impressively so—but she had bet her future on his basic decency. He patted his horse, he fed the beast treats, he took off his spurs before calling on a lady, and his retainers were all so venerable they could nearly recall when York was a Viking capital.

A truly dishonorable peer would discard elderly servants and abuse his cattle, wouldn’t he?

The tea tray arrived before Althea could doubt herself further, and in keeping with standing instructions, the kitchen had exerted its skills to the utmost. Strensall placed an enormous silver tray before Althea—the good silver, not the fancy silver—bowed, and withdrew.

“How do you take your tea, Your Grace?”

“Plain, except I won’t be staying for tea. Assure me that you’ll send your swineherd over to collect your sows in the next twenty-four hours and I will take my leave of you.”

Not so fast. Having coaxed Rothhaven into making a call, Althea wasn’t about to let him win free so easily.

“I cannot give you those assurances, Your Grace, much as I’d like to. I’m very fond of those ladies and they are quite valuable. They are also particular.”

Rothhaven straightened a crease in his breeches. They fit him exquisitely, though Althea had never before seen black riding attire.

“The whims of your livestock are no affair of mine, Lady Althea.” His tone said that Althea’s whims were a matter of equal indifference to him. “You either retrieve them or the entire shire will be redolent of smoking bacon.”

He was bluffing, albeit convincingly. Nobody butchered hogs in early spring, for any number of reasons. “Do you know what my sows are worth?”

He quoted a price per pound for pork on the hoof that was accurate to the penny.

“Wrong,” Althea said, pouring him a cup of tea and holding it out to him. “Those are my best breeders. I chose their grandmamas and mamas for hardiness and the ability to produce sizable, healthy litters. A pig in the garden can be the difference between a family making it through winter or starving, if that pig can also produce large, thriving litters. She can live on scraps, she needs very little care, and she will see a dozen piglets raised to weaning twice a year without putting any additional strain on the family budget.”

The duke looked at the steaming cup of tea, then at Althea, then back at the cup. This was the best China black she could offer, served on the good porcelain in her personal parlor. If he disdained her hospitality now, she might…cry?

He would not be swayed by tears, but he apparently could be tempted by a perfect cup of tea.

“You raise hogs as a charitable undertaking?” he asked.

“I raise them for all sorts of reasons, and I donate many to the poor of the parish.”

“Why not donate money?” He took a cautious sip of his tea. “One can spend coin on what’s most necessary, and many of the poor have no gardens.”

“If they lack a garden, they can send the children into the countryside to gather rocks and build drystone walls, can’t they? After a season or two, the pig will have rendered the soil of its enclosure very fertile indeed, and the enclosure can be moved. Coin, by contrast, can be stolen.”

Another sip. “From the poor box?”

“Of course from the poor box. Or that money can be wasted on Bibles while children go hungry.”

This was the wrong conversational direction, too close to Althea’s heart, too far from her dreams.

“My neighbor is a radical,” Rothhaven mused. “And she conquers poverty and ducal privacy alike with an army of sows. Nonetheless, those hogs are where they don’t belong, and possession is nine-tenths of the law. Move them or I will do as I see fit with them.”

“If you harm my pigs or disperse that herd for sale, I will sue you for conversion. You gained control of my property legally—pigs will wander—but if you waste those pigs or convert my herd for your own gain, I will take you to court.”

Althea put three sandwiches on a plate and offered it to him. She’d lose her suit for conversion, not because she was wrong on the law—she was correct—but because he was a duke, and not just any duke. He was the much-treasured Dread Duke of Rothhaven Hall, a local fixture of pride. The squires in the area were more protective of Rothhaven’s consequence than they were of their own.

Lawsuits were scandalous, however, especially between neighbors or family members. They were also messy, involving appearances in court and meetings with solicitors and barristers. A man who seldom left his property and refused to receive callers would avoid those tribulations at all costs.

Rothhaven set down the plate. “What must I do to inspire you to retrieve your valuable sows? I have my own swineherd, you know. A capable old fellow who has been wrangling hogs for more than half a century. He can move your livestock to the king’s highway.”

Althea hadn’t considered this possibility, but she dared not blow retreat. “My sows are partial to their own swineherd. They’ll follow him anywhere, though after rioting about the neighborhood on their own, they will require time to recover. They’ve been out dancing all night, so to speak, and must have a lie-in.”

Althea could not fathom why any sensible female would comport herself thus, but every spring she dragged herself south, and subjected herself to the same inanity for the duration of the London Season.

This year would be different.

“So send your swineherd to fetch them tomorrow,” Rothhaven said, taking a bite of a beef sandwich. “My swineherd will assist, and I need never darken your door again—nor you, mine.” He sent her a pointed look, one that scolded without saying a word.

Althea’s brother Quinn had learned to deliver such looks, and his duchess had honed the raised eyebrow to a delicate art.

While I am a laughingstock. A memory came to Althea, of turning down the room with a peer’s heir, a handsome, well-liked man tall enough to look past her shoulder. The entire time they’d been waltzing, he’d been rolling his eyes at his friends, affecting looks of long-suffering martyrdom, and holding Althea up as an object of ridicule, even as he’d hunted her fortune and made remarks intended to flatter.

She had not realized his game until her own sister, Constance, had reported it to her in the carriage on the way home. The hostess had not intervened, nor had any chaperone or gentleman called the young dandy to account. He had thanked Althea for the dance and escorted her to her next partner with all the courtesy in the world, and she’d been the butt of another joke.

“I cannot oblige you, Your Grace,” Althea said. “My swineherd is visiting his sister in York and won’t be back until week’s end. I do apologize for the delay, though if turning my pigs loose in your orchard has occasioned this introduction, then I’m glad for it. I value my privacy too, but I am at my wit’s end and must consult you on a matter of some delicacy.”

He gestured with half a sandwich. “All the way at your wit’s end? What has caused you to travel that long and arduous trail?”

Polite society. Wealth. Standing. All the great boons Althea had once envied and had so little ability to manage.

“I want a baby,” she said, not at all how she’d planned to state her situation.

Rothhaven put down his plate slowly, as if a wild creature had come snorting and snapping into the parlor. “Are you utterly demented? One doesn’t announce such a thing, and I am in no position to…” He stood, his height once again creating an impression of towering disdain. “I will see myself out.”

Althea rose as well, and though Rothhaven could toss her behind the sofa one-handed, she made her words count.

“Do not flatter yourself, Your Grace. Only a fool would seek to procreate with a petulant, moody, withdrawn, arrogant specimen such as you. I want a family, exactly the goal every girl is raised to treasure. There’s nothing shameful or inappropriate about that. Until I learn to comport myself as the sister of a duke ought, I have no hope of making an acceptable match. You are a duke. If anybody understands the challenge I face, you do. You have five hundred years of breeding and family history to call upon, while I…”

Oh, this was not the eloquent explanation she’d rehearsed, and Rothhaven’s expression had become unreadable.

He gestured with a large hand. “While you…?”

Althea had tried inviting him to tea, then to dinner. She’d tried calling upon him. She’d ridden the bridle paths for hours in hopes of meeting him by chance, only to see him galloping over the moors, heedless of anything so tame as a bridle path.

She’d called on him twice, only to be turned away at the door and chided by letter twice for presuming even that much. Althea had only a single weapon left in her arsenal, a lone arrow in her quiver of strategies, the one least likely to yield the desired result.

She had the truth. “I need your help,” she said, subsiding into her chair. “I haven’t anywhere else to turn. If I’m not to spend the rest of my life as a laughingstock, if I’m to have a prayer of finding a suitable match, I need your help.”

Chapter Two

Lady Althea sat before Nathaniel, her head bent, her fists bunched in her lap. Ladies did not make fists. Ladies did not boast of breeding hogs. Ladies did not refer to ducal neighbors as petulant, moody, withdrawn, and arrogant, though Nathaniel had carefully cultivated a reputation as exactly that.

But those disagreeable characteristics were not the real man, he assured himself. He was in truth a fellow managing as best he could under trying circumstances.

I am not an ogre. Not yet. “I regret that I cannot assist you. I’m sorry, my lady. I’ll bid you good day.”

“You choose not to assist me.” She rose, skirts swishing, and glowered up at him. “I am the only person in this parish whose rank even approaches your own, and you disdain to give me a fair hearing. What is so damned irresistible about returning to the dreary pile of stone where you bide that you cannot be bothered to even finish a cup of tea with me?”

Nathaniel was sick of his dreary pile of stone, to the point that he was tempted to howl at the moon.

“We have not been introduced,” he retorted. “This is not a social call.”

She folded her arms, her bearing rife with contempt. “That mattered to you not at all when a few loose pigs wandered into your almighty orchard. You do leave your property, Your Grace. You gallop the neighborhood at dawn and dusk, when there’s enough light to see by, but you choose the hours when other riders are unlikely to be abroad.”

Lady Althea was unremarkable in appearance—medium height, dark brown hair. Nothing to rhapsodize about there. Her figure was nicely curved, even a bit on the sturdy side, and her brown velvet day dress lacked lace and frills, for all it was well cut and of excellent cloth.

What prevented Nathaniel from marching for the door was the force of her ladyship’s gaze. She let him see both vulnerability and rage in her eyes, both despair and dignity. Five years ago, Robbie had looked out on the world from the same place of torment. What tribulations could Lady Althea have suffered that compared with what Robbie had endured?

“You gallop everywhere,” she said, a judge reading out a list of charges, “because a sedate trot might encourage others to greet you, or worse, to attempt to engage you in conversation.”

Holy thunder, she was right. Nathaniel had developed the strategy of the perpetual gallop out of desperation.

“You travel to and from the vicarage under cover of darkness,” she went on, “probably to play chess or cribbage with Dr. Sorenson, for it’s common knowledge that your eternal soul is beyond redemption.”

Nathaniel’s visits to the vicarage—his sole social reprieve—would soon be over for the season. In December, a Yorkshire night held more than sixteen hours of darkness. By June, that figure halved, with the sky remaining light well past ten o’clock.

“Do you spy on me, Lady Althea?”

“The entire neighborhood notes your comings and goings, though I doubt your Tuesday night outings have been remarked upon. T. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...