- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

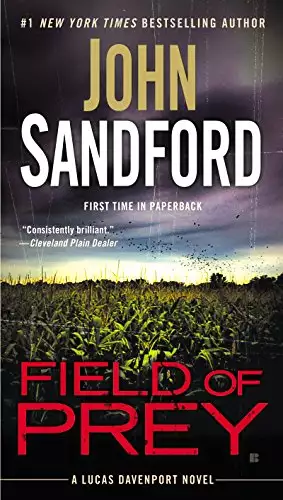

Synopsis

Layton had picked the perfect spot to lose his virginity to his girlfriend, an abandoned farmyard in the middle of cornfields. The only problem was something smelled bad... He mentioned it to a county deputy he knew and when they looked, they found a body stuffed down a cistern. By the time Lucas Davenport was called in, the police were up to fifteen bodies and counting. The victims had been killed over many years, one every summer. How could this have happened without anybody noticing?

Release date: May 6, 2014

Publisher: G.P. Putnam's Sons

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Field of Prey

John Sandford

YEARS AGO . . .

The fifth woman was a blond waitress who enhanced her income by staying late to do kitchen cleanup at Auntie’s, a diner in Faribault, a small city on Interstate 35 south of the Twin Cities. The diner had excellent qualities for a kidnapping. The blacktop parking lot was wide and deep in front, shallow and pitted in back, which meant that nobody parked there. When the fifth woman finished her cleanup, at midnight, she’d haul garbage bags to a dumpster out back.

In the dark.

She was out there alone, sweating in the summer heat, sickened by the odor from the dumpster, with no light except what came through the diner’s open rear door and two pole lights in the front lot.

R-A waited for her there, hidden behind the dumpster. He was carrying an old canvas postal bag, of the kind once used to carry heavy loads of mail in cross-country trucks. The bags, forty-eight inches long and more than two feet in diameter, had eyelets around the mouth, with a rope running through the eyelets. The rope could be cinched tight with a heavy metal clasp.

R-A also carried a leather-wrapped, shot-filled sap, in case something went wrong with the bag.

Horn sat in his truck, in an adjacent parking lot, no more than a hundred feet away, where he could see the action at the dumpster, and warn against any oncoming cop cars. When the waitress came out with her second load of garbage bags, R-A waited until she was standing on tiptoe, off-balance while throwing one of the bags into the dumpster. He stepped out behind her, unseen, and dropped the canvas bag over her head, like a butterfly in a net.

The woman struggled and fought, and screamed, but the screams were muffled by the heavy bag, and two seconds after he took her to the ground, R-A slipped the locking clasp tight around her legs.

Horn was coming, in the truck. He stopped beside them, blocking the view from the street. Together, Horn and R-A lifted her and threw her in the back of Horn’s extended cab truck. Horn climbed in on top of her with a roll of duct tape, and threw a half dozen fast wraps around the woman’s ankles. Sort of like calf-roping, he thought.

As he did that, R-A jogged a half-block down the street to where he’d parked his own truck. When Horn had finished taping the woman’s ankles, he jumped out and slammed the narrow door, ran around the back of the truck and climbed into the driver’s seat, and they were gone, Horn a half-block ahead of R-A.

The system had worked again.

In three minutes, they’d gotten to the edge of town and were starting cross-country toward a hunter’s shack in the backwaters of a Mississippi River impoundment. There, they’d rape the waitress and kill her.

R-A trailed a half-mile behind Horn. That was part of the system, too. If a cop car came along, and showed any interest at all in Horn’s truck, R-A could provide warning, and support. If worse came to worst, R-A would drive recklessly and way too fast past the cop, provoking a chase, while Horn would re-route.

• • •

THE SYSTEM HAD WORKED BEFORE, and would have worked again, except that Heather Jorgenson had always worried about being alone in that parking lot in the night. She carried a Leatherman multi-tool, which included a three-inch-long serrated blade, in the pocket of her waitress uniform, and while her feet were restricted by the locked bag and the duct tape, her hands were free.

For the first minute or so of the truck ride, she fought with a panic-stricken violence against the heavy bag, without making any progress at all. In the thrashing, her hand slapped against the Leatherman.

The knife!

She fumbled it out and broke a nail trying to get it open, but hardly noticed; three minutes into the ride, she had the knife out and open. Jorgenson knew she’d only have one chance at it, so she continued to shout and scream, and thrash with one hand, as the truck drove through town. At the same time, she slit the bag with the razor-sharp blade, and at the bottom end, cut the binding rope around her legs. Finally, she carefully sliced through the duct tape at her ankles.

She took a moment to get her courage up, then pushed herself up in the back of the truck, and screaming, “You sonofabitch,” she stabbed Horn in the neck, and then stabbed him again, in the back, in the spine, and then in the arms, and in the neck again, and Horn was shouting, screaming, trying to swat her away, while struggling to control the truck. He failed, and the truck swerved to the left edge of the road, two wheels dropping off the tarmac. They ran along like that for a hundred feet, then the truck began to tip, and finally rolled over into the ditch.

Jorgenson, in the back, felt the truck going. A former cheerleader, still with a cheerleader’s suppleness, despite the extra pounds she’d picked up in the diner, she braced her feet against the roof of the truck and locked herself in place as it went over. When it settled, driver’s side down, she found the handle on the back door, unlocked it, shoved it open, and crawled out.

She ran across the roadside ditch, tumbled over a barbed-wire fence, ripping her clothes and hands, into a cornfield—she was afraid to run down the road, because the kidnapper could see her, might come after her.

They’d just left town, and there were house lights no more than four or five hundred yards away. She ran as hard as she could, choking with fear, through the knee-high corn, then fell again and found herself in a mid-field swale, a seasonal creek, dry now.

Breathing hard, she crouched for a moment, listening, fearing that the kidnapper was right behind her. When she heard nothing, she got to her feet, stooped over so far that her hands touched the ground, and groped forward in the dark, toward the house lights.

She had no idea how long she’d been in the field when she made it into a tree line, the branches of the saplings slapping her in the face and chest. She crossed another fence and a ditch, out onto a road, then ran across the road toward the house lights. She was now so frightened and exhausted that she took no care about waking the house. She leaned on the lighted doorbell and pounded on the door while screaming, “Help! Help me!”

• • •

THE COPS were there in five minutes.

They found an upside-down truck with lots of blood in the front seat, and the cut-open mail sack in the back. They traced the truck in another five minutes, and were on their way to Horn’s house in ten.

• • •

WHEN R-A GOT TO Horn’s truck, the woman was gone.

Horn groaned, “I’m hurt, man, I’m hurt bad.”

“Where is she?” R-A asked.

“She ran off, she’s gone, man, we gotta get out of here.” Horn was crumpled onto the driver’s side window of the truck. R-A was kneeling on the narrow back door on the passenger side, looking down into the truck, the front door propped half open. “Help me out, help me.”

Horn was covered with blood, down to his waist. R-A pulled him out of the truck, but Horn couldn’t walk: “Did something to my legs, they don’t work . . .”

R-A carried him to his own truck, put him in the back, and told him to stay down. “The hospital . . .”

“Fuck that. Fuck the hospital,” Horn said. “They’re gonna find my truck. The bitch knows my face, from the scouting trips. She’ll pick me out.”

“Then where?”

“Your place,” Horn groaned. “They’ll be at my place, sure as shit.”

• • •

R-A GOT HIM BACK to his place, managed to half-drag, half-carry him down to the basement bomb shelter. Put him on a cot, plastered his wounds the best he could.

Thought about killing him. Horn’s legs didn’t work, he could never be anything but a liability. But R-A couldn’t do it: Horn was the closest thing he’d ever had to a friend.

• • •

HORN MADE THE TV the next morning: Heather Jorgenson, according to police reports, said she’d been attacked by a man in the parking lot behind Auntie’s, and had stabbed him. The police were looking for Jack Horn, of Holbein. Jack Horn, singular. No mention of two men. R-A cruised by his house, and the cops were all over it.

Horn himself, down in the bomb shelter, was drifting in and out of consciousness. In one of his lucid moments, he saw R-A staring at him.

“What’re you staring at?” he mumbled. And, “Water. I need a drink. Need some . . . medicine.”

R-A ran a country hardware store, with veterinary medicine in a locked cabinet at the back. Horn was out of it, so never felt the horse-sized needle that R-A used to give him the penicillin.

• • •

HORN WAS still in and out. During one of his lucid moments, R-A told Horn that the cops had taken his truck away, and that there was a warrant out for him, for kidnapping. “They’re looking for you everywhere between Chicago and Billings. You can’t look at the TV without seeing your ugly face.”

“Water,” said Horn. R-A went away and came back with a glass of water, but Horn found he couldn’t even lift his hand. R-A poured it awkwardly into Horn’s open, trembling mouth.

“How long?” he said, when he found his voice again.

“You’ve been up and down for two days,” R-A said. A pause. “Mostly down.”

“No hospital . . .” Horn said.

“If I don’t, I figure you’ll die,” R-A said. “Then what’ll I do?”

“No hospital . . .” Horn repeated. And then he was gone again.

It went like that for two more days; by the end of the second day, the bomb shelter smelled like an unclean hospital room, with the stink of human waste and corruption.

Then, on a Friday, R-A got back from the store and found Horn deathly still, his face as pale and gray as newsprint. At first, R-A thought him dead. That would have . . . made things easier. He could get rid of the body, and still feel he’d filled the requirements of male comradeship.

Then Horn opened his eyes and said in a calm voice, “You been thinking about choking me out, haven’t you?”

“The thought crossed my mind,” R-A admitted.

“No need, now. Things are different now.”

“Yeah, I . . .”

“I been thinking about it. This is the perfect place. You’re going to have to start bringing the girls here.”

“I . . . thought I might stop.”

Horn grunted: “Roger—you can’t stop. But there’s no more banging them out in the woods. That’s all done. . . . Now you’ll have to bring them down here. Look around. It’s perfect. Down here, we can keep them for a while. Half the trouble, twice the fun.”

And it’d worked. For a very long time.

1

There comes a crystalline moment in the lives of most young male virgins when they realize that they are about to get laid, and they will clutch that moment to their hearts for the rest of their days.

For some, maybe most, the realization comes nearly simultaneously with the moment. With others, not so much.

For Layton Burns Jr., of Red Wing, Minnesota, a recent graduate of Red Wing High School (Go Wingers!), the moment arrived on the night of the Fourth of July. He and Ginger Childs were wrapped in a blanket and propped against a tree of some sort—neither was a botanist—in a park in Stillwater, Minnesota, looking down at the river, where the fireworks were going off.

Fireworks were not going off in Red Wing, because the city council was too cheap to pay for them.

In any case, Stillwater did have fireworks. Layton, a jock, had his muscular right arm wrapped around Ginger’s back, then under her arm and in past the unbuttoned second button on her blouse, where he was getting, in the approved parlance of the senior class at Red Wing High School, a bare tit. One of those hot, nipple-rolling bare tits. Not only a bare tit, but a semi-public one, which added to the frisson of the moment.

While intensely pleasant, this was not entirely a new development. They’d taken petting to a fever pitch, but Layton was the tiniest bit shy about asking for the Big One.

Ginger had her hand on Layton’s thigh, where, despite his shyness, his interest was evident, and then as the final airbursts exploded in red-white-and-blue over the hundred boats in the harbor below, Ginger turned and bit him lightly on the earlobe and muttered, “Oh, God, if only you had some . . . protection.”

• • •

UNTIL THAT VERY MOMENT, one of the few people in Red Wing who wasn’t sure that Layton was going to get laid that summer was Layton himself. His parents knew, her parents knew, Ginger knew, all of Layton’s friends knew, all of Ginger’s friends knew, and Ginger’s youngest sister, who was nine, strongly suspected.

But Layton, there in the park, wasn’t organized for the moment. He groaned and said, in words made memorable by thousands of impromptu daddies, “Nothin’ll happen.”

“Can’t take a chance,” said Ginger, who was no dummy, and for whom, not to put it too bluntly, Layton was more or less a passing bump in the night. “Do you think by tomorrow night?”

Wul, yeah.

• • •

BY THE NEXT NIGHT, Layton was organized.

He’d gotten the green light to borrow his mom’s three-year-old Dodge Grand Caravan, which had Super Stow ’n Go seating in the back, converting instantly into a mobile bedroom. He’d stashed a Target air mattress and a six-pack of Coors with a friend. And he’d stolen three, no make it four, lubricated condoms from a twelve-pack that his father had conveniently left unhidden in the second drawer of his bedroom bureau, for the very purpose of being stolen by his son, his wife being on the pill.

Layton also had the perfect spot, discovered a year earlier when he was detasseling corn. The perfect spot had once been a farmyard with a small woodlot on the north side. The farm had failed decades earlier. Most of the land had been sold off, and the house had fallen into ruin and had eventually been burned by the local volunteer fire department in a training exercise. The outbuildings had either been torn down or had simply rotted in place. Still, the home site had not yet been plowed under, though the cornfields were pressing close to the sides of the old yard.

A narrow track, once a driveway, led across a culvert into the site; and there were good level places to park. An hour before he was to pick up Ginger, Layton signed onto his computer and went out to his favorite porn site to review his knowledge of female anatomy; which also reminded him to put a flashlight in the car in case he wanted to . . . you know . . . watch.

• • •

LAYTON HAD BUILT a sex machine, and it worked flawlessly.

He got the beer and air mattress from his friend, picked up Ginger, and they headed west on Highway 58, out of the Mississippi River Valley, up on top, then down through the Hay Creek Valley, up on top again, and out into farm country. The ride was short and sweet in the warm summer night, with fireflies in the ditches and Lil Wayne on the satellite radio, which was a good thing, because Ginger was hotter than a stovepipe, and had her hand in Layton’s jeans before they even got off the main highway and onto the back roads.

They found the turnoff into the farm lot on the first try, pushed aside some senile, overgrown lilacs as they wedged into a parking space, pumped up the air mattress with an air pump powered through the cigarette lighter, and got right to it.

There was some confusion at the beginning, when Layton unrolled the first rubber, rather than rolling it down the erect appendage, and was reduced to trying to pull it on like a sock. A bit later, if Layton had been more attentive, he might have noticed that Ginger knew a good deal about technique and positioning, but he was not in a condition to notice; nor would he have given a rat’s ass.

And it all went fine.

They did it twice, stopped for a beer, and then did it again, and stopped for another beer, and Layton was beginning to regret that he hadn’t stolen five rubbers, when Ginger said, demurely, “I kinda got to go outside.”

“What?”

“You know . . .”

She had to pee. Layton finally got the message and Ginger disappeared into the dark, with the flashlight. She was back two minutes later.

“Boy, something smells really bad out there.”

“Yeah?” He didn’t care. She didn’t care much either, especially as she’d reminded him about the flashlight.

So they messed around with the flashlight for a while, and Ginger said, “You’re really large,” which made him feel pretty good, although he’d measured himself several dozen times and it always came out at six and one-quarter inches, which numerous Internet sources said was almost exactly average.

Anyway, the fourth condom got used and stuffed in the sack the beer had come in, and Layton began to see the limits of endurance even for an eighteen-year-old—he probably wouldn’t have needed the fifth one. They lay naked in each other’s arms and drank the fifth and sixth beers and Ginger burped and said, “We probably ought to get back and establish our alibis,” and Layton said, “Yeah, but . . . I kinda got to go outside.”

Ginger laughed and said, “I wondered about that. You must have a bladder like an oil drum.”

“I’m going,” he said. He took the flashlight and moved off into the trees, wearing nothing but his Nike Airs, found a spot, and as he was taking the leak, smelled the smell: and Ginger was right. Something really stank.

It was impossible to grow up in the countryside and not know the odor of summertime roadkill, and that’s what it was. Something big was dead and rotting, and close by.

He finished and went back to the car and found Ginger in her underpants, and getting into her jean shorts. “I want to go out and look around for a minute,” he said. In the back of his mind he noticed his own sexual coolness. Even though her breasts were right there, and as attractive and pink and perky as they’d been fifteen minutes ago, he could have played chess, if he’d known how to play chess. “There’s something dead out there.”

“That’s the stink I told you about.”

“Not an ordinary stink,” Layton said. “Whatever it is, is big.”

She stopped dressing: “You mean . . . like a body?”

“Like something. Man, it really stinks.”

When they were dressed, and with Ginger holding onto the back of Layton’s belt, they walked into the woods—as if neither one of them had ever seen a Halloween movie—following the light of the flash. As they got deeper in, the smell seemed to fade. “Wrong way,” Layton said.

They turned back and Ginger said, “Hope the light holds out.”

“It’s fine,” Layton said. Fresh batteries: Layton had been ready.

They walked back toward the area where the house had been, and the smell grew stronger, until Ginger bent and gagged. “God . . . what is it?”

Whatever it was, they couldn’t find it. Layton marched back and forth over the old farmstead, shining the light into the underbrush and even up into the trees. They found nothing.

“Don’t ghosts smell?” Ginger said. “I saw it on one of those British ghost-hunter shows, that sometimes ghosts make a bad smell.”

Every hair on Layton’s neck stood up: “Let’s get out of here,” he said.

They started walking back to the car, but by the time they got back, they were running. They jumped in, slammed the doors, clicked the locks, backed out of the parking place, and blasted off down the gravel road, not slowing until they got to the highway. The bag with the used condoms and the empty beer cans went into an overgrown ditch, and fifteen minutes later, they were headed down the hill into the welcoming lights of Red Wing.

• • •

LAYTON LAY IN BED that night and thought about it all—mostly the sex, but also about Ginger’s best friend, Lauren, and what a wicked threesome that would be, and about that awful odor. Ginger called him the next morning to say it had been the most wonderful night of her life; and he told her that it had been the most wonderful night of his.

The night had been wonderful, but not quite perfect. There’d been that smell.

• • •

LAYTON’S BEST FRIEND’S older brother was a Goodhue County deputy named Randy Lipsky, who was only six or eight years older than Layton. If not quite a friend, he was something more than an acquaintance.

Layton got up late, shaved, ate some Cheerios, and still not sure if he was doing the right thing, called the sheriff’s office and asked if Lipsky was around. He was.

“I need to talk to you for a minute, if I could run over there,” Layton said.

So he went over to the law enforcement center, found Lipsky, and they walked around the block.

Layton said, “Just between you and me.”

“Depending on what it is,” Lipsky said. “I’m a cop.”

“Well, I didn’t do anything,” Layton said.

“What is it?” Lipsky asked.

“Last night, my girlfriend and I went up to this old farm place, out in the country, and parked for a while.”

“Ginger?”

“Uh-huh.”

“She’s pretty hot. You nail her?”

“Hey . . . But, yeah, as a matter of fact.” He was so cool about it that ice cubes could have rolled out of his ears.

“Anyway . . .”

“Anyway, there’s something dead up there. Something big. I never smelled anything like it. I thought it was a cow or a pig. The weird thing is, we couldn’t find anything, and there aren’t any dairies or pig farms around there. We could smell it, like it was right there: like we were standing on it. It made Ginger throw up it was so strong. I was thinking last night, what if we couldn’t find it because . . . somebody buried something?”

“You mean . . .” Lipsky stopped and looked at Layton. Layton was a jock, but not an idiot.

“Yeah. I thought I should ask,” Layton said. “Now you can tell me I’m a whiny little girl, and we can forget about it.”

Lipsky said: “I’ll tell you something, Layton: ninety-five percent it’s nothing. Probably somebody shot a buck out of season, and you were smelling the gut dump. Those can be pretty hard to see in the dark, once they go gray. But, five percent, we gotta go look.”

Lipsky went to get a patrol car and Layton called Ginger and told her what he’d done. “Well, God, don’t mention me,” she said.

“If it’s something, I’ll probably have to,” he said.

“Well, if it’s something . . . sure. I worried about it, too, last night,” she said. “Like you were saying, it smelled big. What if it’s a dead body?”

“I’ll call you when we get back,” Layton said.

• • •

THE DRIVE IN THE DAYTIME was even faster than the drive the night before, out into the countryside and the hot July sun. Layton pointed Lipsky into the abandoned farm lot and Lipsky said, “What a great place to park.”

“Yeah, it’d be okay, if it didn’t stink so bad,” Layton said. “Over here.”

He led the way back where the old house had been, and the smell was like a wall. They hit it and Lipsky’s face crinkled and he said, “Jesus Christ on a crutch.”

“I told you,” Layton said.

“Where’s it coming from?” Lipsky asked.

They quartered the area, kicking through the underbrush, and eventually always came back to the yard where the house had been, and finally Lipsky pointed to the edge of the clearing and said, “Go over and pull out that old fence post, and bring it back here.”

• • •

THE FENCE POST WAS a rusting length of steel still attached to a single strand of barbed wire. Layton wrenched it loose, pulled the barbed wire off, and carried it back to Lipsky. Lipsky was walking around a patch of fescue grass twenty feet across, a distracted look on his face.

“What do you think?” Layton asked.

“Might be an old cistern here, or an old well,” Lipsky said. “You see that line in the grass?”

“Maybe . . .”

Lipsky took the fence post from Layton and began probing the patch of grass. He’d done it four times when, on the fifth, there was a hollow thunk.

“There it is,” Lipsky said. “Should have been filled in, doesn’t sound like it was.”

He scraped around with the fence post and found the edge of the cistern cover, which was a circular piece of concrete. A whole pad of fescue lifted off it, in one piece, and Lipsky said, “Just between you and me, I don’t think we’re the first ones to do this.”

“Maybe we ought to call the cops,” Layton said. Lipsky gave him a look, and Layton said, “You know what I mean. More cops.”

“Let’s just take a look,” Lipsky said.

They pulled the grass off, and Lipsky said, “Check this out.”

One edge of the concrete cover showed what seemed to be recent scrapes, perhaps made with a pick, or a crowbar; and all around the edges, older scrapes. Lots of them. Lipsky found a place where he could get the good end of the fence post under the rim of the cistern cover, and pried. There was a pop when it came loose, and the gas hit them and they both reeled away, gagging, vomiting into the grass away from the cistern.

When they’d vomited everything in their stomachs—Lipsky had gone to his hands and knees—they went back and looked into the cistern, but all they saw was darkness.

“Let me get a flash,” Lipsky said. “Don’t fall in.” He spit into the weeds as he went, and then spit again, and Layton spit a couple times himself, his mouth sour from the vomit.

Lipsky got the flashlight and walked back to where Layton was standing, his forearm bent over his nose.

They looked into the hole and Lipsky turned on the six-cell Maglite, and they first saw the two white ovals.

“Is that . . . ?” Layton asked.

“What?” Lipsky looked like he didn’t want to hear it.

“Feet? It looks like the bottoms of somebody’s feet,” Layton said.

Lipsky turned back toward the squad car.

“Where’re you going?” Layton asked.

“To call the cops,” Lipsky said. “More cops. Lotsa cops.”

2

The Bureau of Criminal Apprehension is housed in a modern redbrick-and-glass building in St. Paul, Minnesota. Lucas Davenport had once explained the somewhat odd name to an agent of the Federal Bureau of Investigation this way: “In Minnesota, see, we actually apprehend the assholes, instead of just investigating them.”

The fed said, “Really? Doesn’t that get you in trouble? I’d think the paperwork would be a nightmare.”

Lucas parked his Porsche 911 in the lot below his office window, where he could keep an eye on it. The last time he’d parked it out of eyesight, somebody had stuck a vegan bumper sticker on it th

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...