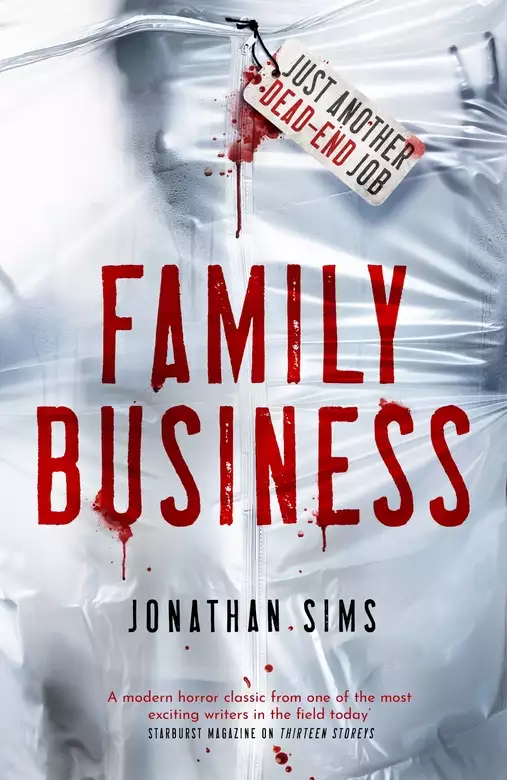

Family Business

- eBook

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

A bone-chilling horror from the acclaimed writer of THIRTEEN STOREYS and hit horror podcast THE MAGNUS ARCHIVES

JUST ANOTHER DEAD-END JOB.

DEATH. IT'S A DIRTY BUSINESS.

When Diya Burman's best friend Angie dies, it feels like her own life is falling apart. Wanting a fresh start, she joins Slough & Sons - a family firm that cleans up after the recently deceased.

Old love letters. Porcelain dolls. Broken trinkets. Clearing away the remnants of other people's lives, Diya begins to see things. Horrible things. Things that get harder and harder to write off as merely her grieving imagination. All is not as it seems with the Slough family. Why won't they speak about their own recent loss? And who is the strange man that keeps turning up at their jobs?

If Diya's not careful, she might just end up getting buried under the family tree. . .

People can't look away from Family Business:

'Great horror novel that gets scarier by the page!' Netgalley reviewer, ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐

'Sims is a master of the horror genre . . . perfect for Halloween reading' Netgalley reviewer, ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐

'Very much in the style of Stephen King . . . [this story will make you] fear to turn the page. A great read' Netgalley reviewer, ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐

Release date: October 13, 2022

Publisher: Orion

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Family Business

Jonathan Sims

Luckily, there are many extremely effective bleach-based or enzymatic chemical products that can be used to clean them away. So many products, in fact, that as Diya Burman found herself heading back out to the van yet again to find no-the-other-yellow-bottle, she silently wished the human body didn’t have quite so many types of fluid in it.

She pulled her mask down as she stepped out of the narrow house and took in a deep lungful of the brisk morning air. It could hardly be called fresh, scented as it was with traffic from the nearby Holloway Road, but Diya had lived her whole life in London and was used to it. Besides, it was certainly a refreshing change from the atmosphere inside. Now she just needed to get used to how conspicuous she felt in her Tyvek coveralls. When she’d first put them on, crisp and white, she had worried about how bright they were, standing out against the dull brick of the nearby houses. Now they weren’t so white anymore, and her self-consciousness had shifted to the stains and spatters that covered them. Diya hoped it wasn’t too obvious exactly what they were.

She opened the van’s back door and sorted through an array of brightly coloured bottles and jugs, the labels of which had long since peeled away, haphazardly tossed into buckets. Who organised things like this? How was anybody supposed to find anything? Especially when so many of the items were just faintly fluorescent liquids in unmarked plastic jugs. Diya lingered for a moment with that spike of annoyance, almost enjoying the sharp emotion that managed to pierce the grey fog that had settled in her chest these past few months. When she’d first agreed to take the job, it had been hard to see any way out, but maybe it would turn out irritation was her path out of grief.

It was the sort of thought that would have made Diya smile once.

How long had she been standing here, staring at these bottles? She tried to focus. As disheartening as she was already finding the new job, the idea of getting fired on her first day was enough to shake her out of the fugue. She’d just have to view the well-worn jumble in the back of the van as something that felt reassuringly practical; a marker of a company so comfortable and experienced in their task that they didn’t need the crutch of neatness or organisation. Yeah, that almost felt plausible.

The correct yellow bottle, a particularly virulent-looking detergent, turned out to be hiding behind one of the ladders, but was easy enough to grab once she spotted it. She slammed the door shut, words locking into place to complete the name emblazoned across the back in black, sans serif script: SLOUGH & SONS. And in slightly smaller letters underneath: A CLEAN BREAK. Diya’s chest ached as she read it again. She’d left so much of her life behind, but even so, she only had this job because of Angie. A final gift, of a sort.

A man in a suit hurried past towards the tube station. Commuter time already? How long had she been out here? Diya hurried back inside. She hoped Xen hadn’t noticed how long she’d taken. She hoped Frank hadn’t noticed.

As it was, she needn’t have worried. Xen didn’t even look up as Diya placed the bottle among the other chemicals currently being worked into a profoundly stained sofa. Xen nodded her head to the beat as the tinny sound of ‘vintage’ Napalm Death spilled from her headphones. Diya tapped her on the shoulder and pointed silently to the yellow bottle.

‘Awesome, cheers!’ Xen shouted over the death metal bleeding into her ears. ‘That stuff’s pretty lethal, though, so let’s leave off ‘til after I’ve had a smoke.’

‘Oh, OK. Is it flammable or—?’

Diya realised her friend couldn’t hear a word she was saying. The bottle didn’t seem to have any fire warnings, although it did show a picture of a very dead fish.

Xen pulled back the hood from her bodysuit and put her headphones around her neck. Diya always expected a mane of brightly coloured hair to spill out whenever she did this but, as Xen had told her with some bitterness, there were no wigs allowed on a job, so instead her close-cropped brown hair stood in muted contrast to the dark eyeshadow and intricate tattoo that crept up her throat. She tugged down her dust mask and lit up a long, black cigarette.

‘Sorry, what were you saying?’ Xen took a theatrical drag, expelling smoke from her nostrils.

‘Is that allowed?’

Diya knew the answer even before Xen’s lips turned up in a sardonic smile.

‘Hey,’ Xen took another long puff for emphasis. ‘If the only smell left in this place once we’re done is tobacco, I reckon we’ve probably done a decent job. So quit worrying so much; my dad’s not going to fire you. Relax.’

‘Sure thing.’

Diya couldn’t get the words to sound even vaguely convincing. She wanted to be like Xen Slough, completely herself, confident even when correcting people (‘it’s a z sound, like Xavier’), but this was a whole new world to her, and she hadn’t been the most forthright of people even before she was hired to clean up after the dead.

Xen threw herself back onto the sofa, contemplating the dark patch that didn’t seem much better than it had when they started, and Diya instinctively squirmed at the sight of someone sitting on the awful thing.

‘Don’t think this one’s getting clean,’ Xen said, ignoring her reaction.

‘I thought it would need to be incinerated anyway?’

‘Nah. You only actually need to do that to something that’s got dead guy goo on it, and the old lady died in the bed. I mean, I wouldn’t want to keep this thing, but the landlord was pretty clear he wanted the furniture saved if possible.’

‘So the sofa’s not … That isn’t, uh, biological?’ Diya asked.

‘Dunno. Don’t think so.’ Xen’s eyes flicked to a set of shelves above the sofa.

There were five of them, screwed haphazardly into the walls and now sagging and bowed under the weight of dozens and dozens of sealed glass jars. Each was filled with a thin and murky liquid coloured somewhere between yellowish green and brownish black, which obscured whatever the contents might have been. Diya tried not to stare too hard at them. Within one jar, white globules that might have been ancient pickled eggs seemed to follow her, while what might have been decades-old spinach pressed against the glass of another like sodden strands of hair. There was a single conspicuous space where at some point one of them had clearly fallen onto the sofa, and the wood was discoloured with old drippings. She remembered her mother talking about Aunt Sala’s old house and wondered if it had been anything like this.

‘What’s in them?’ Morbid curiosity climbed up her spine. ‘Is it food? Why aren’t they in the kitchen?’

‘Hoarders,’ Xen said, as she exhaled again. ‘Who the hell knows?’

The tone of disinterest wasn’t malicious, but it still sliced through Diya like a razor, and she felt herself deflate.

‘Well then, wouldn’t it make more sense to start with the jars? Get rid of them first in case another one falls?’

There was a long pause before Xen answered.

‘Yeah, maybe,’ she said, clearly trying to sound like she’d already considered it. ‘But the thing is that, uh, the order of disposal is—’

‘Dad said you couldn’t smoke inside on jobs anymore.’ Mary’s voice came from the next room, cutting off the half-hearted explanation. Xen couldn’t hide her relief, although the tone of Mary’s voice immediately made Diya feel like an accomplice.

‘No, he didn’t,’ Xen called back. ‘Or is he going to start smoking his pipe on the kerb?’

Mary Slough stood in silence in the doorway, her face almost entirely concealed behind facemask, goggles and hood.

‘It’s disrespectful.’

‘Who to? The half-melted old lady we scraped up in the bedroom?’

‘Yes.’

‘Is it going to anger all them ghosties?’ Xen needled, eyes searching for a reaction.

‘I don’t know. Maybe.’ Mary’s tone was level, but sincere. Diya hadn’t talked to her much since getting the job, but there was an intensity to her. Xen and Frank clearly didn’t take it too seriously, but it unnerved Diya slightly.

‘Fuck the dead.’

Xen didn’t say it loudly, but Diya jumped ever so slightly. Whatever Mary’s reaction was, it didn’t make it through the layers of protective clothing, and she turned and walked away.

‘Sorry.’ Xen turned to Diya a bit sheepishly. ‘Probably too harsh. Just don’t want her creeping you out with all her nonsense right out the gate, you know?’

‘It’s all right. I get it.’ Diya faked a smile. ‘First time we hung out it took her five minutes to bring up astral projection.’

‘Yeah, but it’s worse on jobs. She gets really into the whole “lingering spirits” thing. I mean, it’s not like Dad can fire her, but it doesn’t exactly make things easier. George used to indulge her a bit more, but—’

Xen stopped herself short, cutting off the emotion before it had a chance to reach her voice. The Sloughs weren’t ready to talk about George yet.

‘I mean, it does make a kind of sense.’ Diya tried to move on. ‘Frank— uh, your dad’s been doing this since you were kids, right?’

‘And his father, and his father’s father before him …’ Xen said, putting on a thick faux-Yorkshire accent.

‘I just mean she grew up around death. That’s got to leave its mark.’

‘I don’t know what you could possibly mean.’ Xen took a final drag on her Sobrani Black Russian, smoke pouring over her dark lipstick as she exhaled with a flourish.

‘Yeah, my mistake.’ Diya raised an eyebrow.

Xen smiled, the glint of a silver ankh on a black lace choker just visible below her coveralls as she stubbed out the cigarette on a pile of mildewed books.

‘I can’t believe you’re calling my family a bunch of weirdos.’

‘If the coffin fits.’

Xen let out a guffaw of laughter and leapt up from the sofa. Diya found it hard not to smile as well. She hadn’t known Xen long but her new friend had proved herself the only one regularly able to get through the numbness that dogged her.

There was a moment of stillness as the laugh died away, and all at once the claustrophobic air of the cluttered living room pressed in again. The scent of something sweet rotting beneath the piles of old newspapers seemed to reach into the back of Diya’s nostrils even through her mask, and she only just stopped herself from gagging, turning it into a throat-clearing cough. Xen’s hood and mask were already back on and she was halfway up a stepladder, taking down jars.

Diya tried to shake off the sudden oppressive feeling. Xen had warned her how tough the job could be. But she’d needed something that was physical, something more real than “Digital and Market Communications Lead” – a job that had been pushing her to a breakdown even when Angie was still alive. And it didn’t come much more real, much more physical, than this.

‘What, uh, what shall I do now?’

Xen shrugged, not turning round. ‘Ask my dad. I’m sure he’ll have something. Not like there isn’t plenty to do.’

‘Right.’

Diya did her best not to let her voice reflect the drop in her stomach. She made her way around the piles of clothes that lined the corridor, poking her head around each door in turn, squinting past piles of old plastic milk jugs and piles of yellowed magazines, telling herself that she wasn’t relieved whenever it turned out the room behind them was silent. As she got closer and closer to the bedroom, though, that relief turned to apprehension. Was he going to be in there, where the woman had died? Would Diya have to try and keep her focus on her boss as that wet and awful bed waited behind him? Then she opened the door to something that looked like a study and there he was.

Frank Slough’s coverall was the same stained white as all the others, but he was broad enough that even with his back to her there was no mistaking him. He was standing in the middle of the room, in a clearing near a heap of rusted-shut suitcases, making notes on a clipboard and mumbling to himself.

‘Excuse me, Mr S— uh, Frank?’ It felt awkward, given how short a time she’d known the man, but that’s what he had told her to call him.

He turned slowly to face her. His bushy grey moustache wasn’t completely contained by the nose-piece of his mask, so his small eyes seemed to stare at her from behind a wiry nest of hairs.

‘Yeah?’ His voice wasn’t exactly unfriendly, but it seemed willing to become so if he deemed it necessary.

‘Xen, uh … She said she didn’t need my help at the moment. Is there anything else you need me to do?’

Frank inhaled deeply, as though taking in the whole room, then opened his arms and gestured to pretty much everything.

‘It all needs doing,’ he said, dismissing her.

‘Right,’ Diya said quickly. ‘It’s just—’

‘Hm?’ He turned back around and she found herself looking at the floor, reluctant to make eye contact. She tried to collect her thoughts and speak clearly. Yes, it was her first day, but she was thirty years old and she was done being cowed by grumpy managers.

‘Look, I don’t really know how to do this yet. Xen is fine solo and Mary’s doing the bedroom, which she said earlier was “too complicated” for me to learn yet. I know it all needs doing, but a bit of guidance would be really appreciated.’

Diya took a breath. The silence stretched out longer than it should have. Then Frank nodded at a large nylon bag in the corner. It was coloured safety orange and, when she opened it, Diya was presented with a huge number of Ziploc bags of all shapes and sizes.

‘Next of kin want to make sure we send through anything valuable, but don’t fancy digging through it themselves. Find anything worth not dumping and bag it up. Mark if it needs a deep clean of its own.’

His dismissal this time was final. Diya hoisted the surprisingly heavy bag onto her shoulder and hurried out of the study.

Was that the most pleasant conversation she’d had with Frank Slough so far? Hard to say for sure but it was certainly up there. She remembered Xen’s laughter, clapping her on the back as she came trembling out of what had passed for a job interview.

‘I think he likes you!’ she’d said, eyes sparkling with amusement beneath long, seafoam-green hair.

Diya had just shaken her head, letting out the sobs she’d held in as Frank Slough had simply stared at her in stony silence for almost ten minutes while she tried to explain why she wanted the job. But Xen had apparently been right. The job was hers.

The main hall was probably the best place to start her search for ‘valuables’. She could finish with the living room, one of the only places in the gloomy basement flat that had windows to let in the daylight. Working towards the sun felt like a good way to think about it.

She approached the first pile, kneeling to get a sense of its contents. The mound of fabric lay there, garments twisted around and disappearing into each other until it was unclear what sort of clothes Diya was looking at, or whether it was simply a collection of loose rags and material. She pulled away the uppermost piece, which seemed to have once been a cardigan. The holes that ran all through the wool suggested moths, and the hundreds of tiny brown insect corpses still caught in the fibres confirmed it in a shower of tiny insect death.

Diya’s skin crawled inside her suit. She hated moths. When she was young they’d had an infestation of carpet moths. She remembered her father pulling out all the furniture, her mother pouring some sort of foul-smelling dust on those bare, weirdly crunchy patches of missing carpet. She remembered the tiny eggs, all over the carpet like minuscule flecks of grain. It went on for years like that, her father getting angrier each year that the moths returned. She hadn’t understood it back then, the feeling of trespass, of your home seeming to turn against you.

She tossed the ruined cardigan to the side. There was nothing of value left there. The next thing on the pile was an old skirt, once long and dignified in navy blue, now as much of a worn away husk as the cardigan. Then a jumper, handknitted with great care, colourful yarn winding together into an intricate cascading pattern, now rotten and moth-chewed. Someone had made this with love. Diya threw it onto the pile of things without value.

So it went as she proceeded, pile by pile, down the narrow corridor. She hadn’t expected much of the clothing to be considered ‘valuable’ by whatever distant relative was inheriting the possessions of … What was her name? Frank must have told them the name of the lady who died here at some point. Surely, he must have, and then Diya had forgotten. Was that awful of her? Or maybe he hadn’t said. Maybe that was deliberate, part of the whole procedure. It was all just a job, another life to mop up along with the body, until nobody could tell it had been there at all.

That seed of curiosity fired up in her mind once more, cutting through the muting fog. This was her first … client? Maybe this was routine to the others, but Diya should remember the woman’s name.

She’d get used to it, though. Something inside her was sure of that. This was her life now: rummaging through rags, looking for the glint of gold or silver to pass to whoever was left to grieve. Mary didn’t have to go looking for ghosts in these places. The white shapes that passed silently through the halls of the dead weren’t carrying chains, but sponges and bleach. And Diya was one of them, at least until it was her turn for the evidence of her existence to be scrubbed off the floorboards and carted to the incinerator like Angie.

Stifling her tears, Diya tried to level her breathing and cut off this train of thought. It was a job, just like any other, and as much as she really needed it right now, it wasn’t exactly a life sentence. Was it any surprise that she was in a morbid frame of mind, given how her last few months had been and the nature of what she was doing? If she’d told any of her friends or family, they’d probably have warned her away from this sort of work. But she hadn’t, and right now this was where she needed to be. It was just another job. Her life wasn’t over. Even if, right now, it smelled like it was.

Her hand closed on something small and hard, breaking her train of thought. It was only then she realised exactly how repetitive the rhythm of pick up, check over, put down had become. How routine. Was this how quickly it all started to become normal? Her watch said she’d been at it less than an hour but her mouth felt dry and scratchy. She needed to step outside, get some air and drink some water. She went to stand up when she realised that she was still holding whatever it was she had found in the pile. A thin chain dangled from her closed fist and, when she opened it, she saw a small gold heart sitting in her palm. A locket.

Fumbling with the little clasp was awkward in her thick gloves, but after a few moments it popped open. Inside were a pair of faded black-and-white pictures: a smiling young woman with dark, curly hair, and a man who Diya couldn’t really call handsome, but who seemed at least to be happy. Time had done some work on the photographs, but for the most part they seemed to have escaped the decay that pervaded the rest of the house.

Diya stared at the young woman. Was she the one who would someday die, bloated and alone on a bare mattress, entombed by an illness that had blighted her for decades? And what of the young man? A future husband, gone before his time? A youthful love that left when the going got tough? Was this little shining keepsake a reminder of better times or a bitter memento of what might have been? Diya sighed and dropped it into a Ziploc bag, then sealed it shut.

She heard movement behind her. Standing in the doorway was a figure in white coveralls like hers. The height would have indicated it was Mary, but she couldn’t see the face under the figure’s mask. Diya waited for it to say something, trying to shake off uneasiness. There were only the four of them there, after all.

‘Did you find anything?’ Mary’s voice was cheery and Diya exhaled. She was going to need to get used to this whole ‘semi-faceless’ thing.

‘Yeah,’ she replied, tossing over the small bag. ‘Think it might have been the woman that lived here.’

Mary examined the locket.

‘She looks kinda—’ Diya started, before Mary held up her hand for silence.

Slowly, her new colleague peeled away the thick blue rubber glove from her right hand, seemingly oblivious to the state of the corridor around her, and touched her fingertips to the locket that still lay in the sealed bag. Diya could just about make out that her eyes were closed.

‘Are you OK?’ Diya asked as the quiet stretched out.

‘Yes …’ Mary sounded a bit disorientated, but handed the Ziploc bag back over. ‘Thank you.’

When Diya had first properly met Mary, they’d been drinking with Xen at The Prince Edward. It had been easier to brush it off then, among the laughter of strangers, when she’d started talking about spirits and resonances and all the rest of it. Here, among the dust and the rot, it was harder to roll her eyes.

‘Poor old thing,’ Diya said, unsure what else to say.

‘The woman who died here?’

‘Yeah.’

‘I wouldn’t worry about it.’ Mary’s voice was soft. ‘I suspect she is at peace.’

Now the eyeroll came easily. Mary obviously thought she was being cryptic, and Diya really didn’t feel up to getting into it.

‘I mean, my aunt had a hoarding problem, and I think it was kind of an OCD thing. I never saw the place, but my mum always talked about how distressing it was for her. In the end, Liverpool Council had to get involved and … I don’t know. It just really seems to me that this woman needed help she didn’t get.’

‘Maybe.’ Mary didn’t sound like she needed much insight beyond whatever she thought she’d got from the locket.

‘She was just so alone.’ Diya couldn’t get the thought out of her head. She had found precious little that gave any hint as to who the woman had been. The sheer mass of accumulated possessions seemed to obscure the person behind them, rather than to illuminate her. ‘What about the next of kin? They must have known her?’

Mary shrugged. ‘Often in cases like these, the first time they hear about a relative is when they’re being asked to sort out their affairs.’

Diya’s eyes fell on the locket. ‘They’re quick enough to take anything worthwhile.’

‘I guess.’ Mary indicated the rest of the hallway. ‘But in most cases there isn’t much to take. I think sometimes the relatives would rather they didn’t have the bother.’

‘Was it them who hired us for this job?’

‘Don’t think so. Might have been the landlord, maybe. Dad usually deals with all that stuff.’

‘Right.’

There was a pause as Mary put her glove back on. She seemed suddenly sheepish.

‘Sorry, I usually do my … communing on my own. I just thought you might understand.’

‘No, it’s fine.’ Diya shifted uncomfortably. Why would Mary assume that? Just because she’d also lost someone? ‘I was just going to get a bit of air anyway.’

‘All right,’ Mary said lightly, though her expression was hard to read under the mask and goggles. ‘I’d better get back to it.’

And with that she was gone. Diya allowed herself a small sigh of relief. She did think that she could like Mary, but Xen had been right: her sister could be a lot. The old woman’s spirit was at peace, she had said. Staring at the crusty piles of threadbare clothing it didn’t seem possible. It seemed like a life that had ossified while no-one was looking, growing hard and implacable, squeezing the soul who found themselves trapped by it until they succumbed to its crushing pressure.

Diya stepped outside for the briefest of breaks, the cool air sweeping over her, dispelling the gloomy thoughts. Whoever the dead woman was, she had been a person. Not some tragic parable or gruesome metaphor about holding onto the past. She had been a real human being with a real condition and there was no way for Mary or any of them to know how she had felt about that, whether she had been suffering and how. All Diya could say for sure was that nobody had been there for her. She had died alone.

‘Rough day?’ asked an unremarkable man standing next to the skip.

‘Yeah,’ Diya said without thinking, ‘really rough.’

‘It’ll get easier,’ he said lightly. ‘The first one’s always the hardest.’

‘I hope so. Don’t know if I could handle it being much harder,’ Diya said, turning to face him, but he was already strolling away with a smile still just about visible on his face.

Regardless, she felt slightly calmer now. Diya took a deep breath, heading back inside. At least the woman who lived here hadn’t been murdered. Although Diya likely would be, by Frank, if she didn’t get a move on with the valuables. She resumed her sorting, finishing the last of the hallway piles with the discovery of a few buttons that might have been pearl. She felt a bit ghoulish ripping them off the silk blouse they were attached to, but there had been so little silk left that ‘blouse’ was entirely a guess.

After that, the hunt went relatively quickly. It soon became apparent that anything non-metallic was almost certainly too old and decayed to retain much value at all. Even the porcelain had been piled up so haphazardly that most of it was broken or cracked, with the exception of a small collection of porcelain sheep figurines that seemed to have survived in relatively good condition. They were almost certainly worthless kitschy knick-knacks, but Diya bagged them up carefully anyway on the off-chance they were rare or antique.

Aside from that it was the occasional piece of jewellery, some fancy photo frames (empty) and the occasional objet d’art buried under old newspaper or behind a pile of fused-together jigsaw boxes. She did find the name of the woman whose home it had been when she was going through . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...