- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

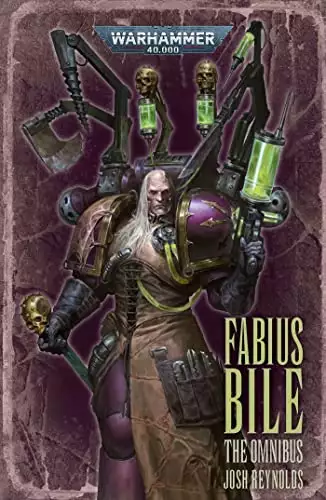

Explore the story of the sinister Fabius Bile in this fantastic value omnibus.

Fabius Bile is known by many names: Primogenitor, Clonelord, Manflayer. Once a loyal son of the Emperor’s Children, now he loathes and is loathed by his brothers. Feared by man and monster, Fabius possesses a knowledge of genetic manipulation second to none, and the will to use it to twist flesh and sculpt nightmares.

Now a traitor amongst traitors, Fabius pursues his dark craft across the galaxy, from the Eye of Terror to the tomb world of Solemnace to the Dark City of Commorragh itself, leaving a trail of monstrous abominations in his wake.

This omnibus edition collects together the novels Primogenitor, Clonelord and Manflayer.

Release date: August 30, 2022

Publisher: Games Workshop

Print pages: 800

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Fabius Bile: The Omnibus

Josh Reynolds

CHAPTER ONE

Dead-Alive

Oleander Koh strode across the dead city, humming softly to himself.

The dry wind scraped across his garishly painted power armour, and he hunched forward, leaning into the teeth of the gale. He relished the way it flayed his exposed skin. He licked at the blood that dripped down his face, savouring the spice of it.

Oleander’s demeanour was at once baroque and barbaric. It was fitting, given that he had left a trail of fire and corpses stretching across centuries. His power armour was the colour of a newly made bruise, and decorated with both obscene imagery and archaic medicae equipment. Animal skins flapped from the rims of his shoulder-plates, and a helmet crested with a ragged mane of silk strips dangled from his equipment belt, amongst the stasis-vials and extra clips of ammunition for the bolt pistol holstered opposite the helmet. Besides the pistol, his only weapon was a long, curved sword. The sword was Tuonela-made, forged in the secret smithy of the mortuary cults, and its golden pommel was wrought in the shape of a death’s head. Oleander was not its first owner, nor, he suspected, would he be its last.

Unlike the weapon, he had been forged on Terra. As Apothecary Oleander, he had marched beneath the banners of the Phoenician, fighting first in the Emperor’s name and then in the Warmaster’s. He had tasted the fruits of war, and found his purpose in the field-laboratories of the being he’d come to call master. The being he had returned to this world to see, though he risked death, or worse, for daring to do so.

He had been forced to land the gunship he’d borrowed some distance away, on the outskirts of the city. It sat hidden now among the shattered husks of hundreds of other craft, its servitor crew waiting for his signal. There was no telling what sort of defences had been erected in his absence. And while he’d sent a coded vox transmission ahead, asking for permission to land, he didn’t feel like taking the risk of being blown out of the sky by someone with an itchy trigger-finger. The few occupants of this place valued their privacy to an almost lunatic degree. But perhaps that was only natural, given their proclivities.

His ceramite-encased fingers tapped out a tuneless rhythm on the sword’s pommel as he walked and hummed. The wind screamed as it washed over him. And not just the wind. The whole planet reverberated with the death-scream of its once-proud population. Their delicate bones carpeted the ground, fused and melted together, though not from a natural heat. If he listened, he could pick out individual strands from the cacophony, like notes from a song. It was as if they were singing just for him. Welcoming him home.

The remains of the city – their city – rose wild around him, a jungle of living bone and wildly growing hummocks of rough psychoplastic flesh. The city might have been beautiful once, but it was gorgeous now. Silent, alien faces clumped on wraithbone walls like pulsing fungi, and living shadows stretched across the streets. Eerie radiances glistened in out-of-the-way places and tittering, phosphorescent shapes skulked in the broken buildings. A verdant madness, living and yet dead. A microcosm of Urum, as a whole.

Urum the Dead-Alive. Crone world, some called it. Urum was not its original name. But it was what the scavengers of the archaeomarkets called it, and it was as good a name as any. For Oleander Koh, it had once simply been ‘home’.

Sometimes it was hard to remember why he’d left in the first place. At other times, it was all too easy. Idly, he reached up to touch the strand of delicate glass philtres hanging from around his thick neck. He stopped. The wind had slackened, as if in anticipation. Oleander grunted and turned. Something was coming. ‘Finally,’ he said.

Gleaming shapes streaked towards him through the ruins. They shone like metal in the sunlight, but nothing made of metal could move so smoothly or so fast. At least nothing he’d ever had the misfortune to meet. They’d been stalking him for a few hours now. Perhaps they’d grown bored with the game. Or maybe he was closer to his goal than he’d thought. The city changed year by year, either growing or decaying. He wasn’t sure which. Perhaps both.

The sentry-beasts were low, lean things. He thought of wolves, though they weren’t anything like that. More akin to the sauroids that inhabited some feral worlds, albeit with feathers of liquid metal rather than scales, and tapering beak-like jaws. They made no noise, save the scraping of bladed limbs across the ground. They split up, and vanished into the shadows of the ruins. Even with his transhuman senses, Oleander was hard-pressed to keep track of them. He sank into a combat stance, fingers resting against the sword’s hilt, and waited. The moment stretched, seconds ticking by. The wind picked up, and his head resounded with the screams of the dead.

He sang along with them for a moment, his voice rising and falling with the wind. It was an old song, older even than Urum. He’d learned it on Laeran, from an addled poet named Castigne. ‘Strange is the night where black stars rise, and strange moons circle through ebon skies… songs that the Hyades shall sing…’

Prompted by instinct, Oleander spun, his sword springing into his hand as if of its own volition. He cut the first of the beasts in two, spilling its steaming guts on the heaving ground. It shrieked and kicked at the air, refusing to die. He stamped on its skull until it lay still. Still singing, he turned. The second had gone for the high ground. He caught a glimpse of it as it prowled above him, stalking through the canopy of bone and meat. He could hear its jagged limbs clicking as it moved. His hand dropped to his pistol.

Something scraped behind him. ‘Clever,’ he murmured. He drew the bolt pistol and whirled, firing. A shimmering body lurched forward and collapsed. Oleander twirled his sword and thrust it backwards, to meet the second beast as it leapt from its perch. Claws scrabbled at his power armour, and curved jaws snapped mindlessly. Its eyes were targeting sensors, sweeping his face for weakness. Oleander stepped back and slammed the point of his sword into one of the twisted trees, dislodging the dying animal.

He prodded the twitching creature with his weapon. It was not a natural thing, with its gleaming feathers and sensor nodes jutting from its flesh like spines. But then, this was not a natural world. The sentry-beast had been vat-grown, built from base acids, stretched and carved into useful shape. Idly, he lifted the blade and sampled the acrid gore that stained it. ‘Piquant,’ he said. ‘With just a hint of the real thing. Your best work yet, master.’

Oleander smiled as he said it. He hadn’t used that word in a long time. Not since he’d last been here. Before Urum’s master, and his, had exiled him for his crimes. Oleander shied away from the thought. Reflecting on those last days was like probing an infected wound, and his memories were tender to the touch. There was no pleasure to be had there, only pain. Some adherents of Slaanesh claimed that those things were ever one and the same, but Oleander knew better.

He kicked the still-twitching body and turned away. Something rattled nearby. The sentry-beasts made no noise, save for that peculiar clicking of their silvery carapace. More of them burst out of the unnatural undergrowth and converged on him. Foolish, to think there were only three. Excess was a virtue here, as everywhere. ‘Well, he who hesitates is lost,’ he said, lunging to meet them. There were ten, at least, though they were moving so swiftly it was hard to keep count.

Beak-like protuberances fastened on his armour as he waded through them. Smooth talon-like appendages scraped paint from the ceramite, and whip-like tails thudded against his legs and chest. They were trying to knock him down. He brought his sword down and split one of the quicksilver shapes in half. Acidic ichor spewed upwards. He fired his bolt pistol, the explosive rounds punching fist-sized holes in his attackers.

All at once, the attack ceased. The surviving sentry-beasts scattered, as swiftly as they had come. Oleander waited, scanning his surroundings. He’d killed three. Someone had called the others off. He thought he knew who. He heard the harsh rasp of breath in humanoid lungs, and smelled the rancid stink of chem-born flesh.

Oleander straightened and sheathed his sword without cleaning it. ‘What are you waiting for, children?’ He held up his bolt pistol and made a show of holstering it. ‘I won’t hurt you, if you’re kind.’ He spread his arms, holding them away from his weapons.

Unnatural shapes, less streamlined than the sentry-beasts, lurched into view. They moved silently, despite the peculiarity of their limbs. They wore the ragged remnants of old uniforms. Some were clad in ill-fitting and piecemeal combat armour. Most carried a variety of firearms in their twisted paws – stubbers, autoguns, lasguns and even a black-powder jezzail. The rest held rust-rimmed blades of varying shapes and sizes.

The only commonality among them was the extent of the malformation that afflicted them. Twisted horns of calcified bone pierced brows and cheeks, or emerged from weeping eye sockets. Iridescent flesh stretched between patches of rank fur or blistered scale. Some were missing limbs, others had too many.

They had been men, once. Now they were nothing but meat. Dull, animal eyes studied him from all sides. There were more of them than there might once have been, which was something of a surprise. Life was hard for such crippled by-blows, especially here, and death the only certainty. ‘Aren’t you handsome fellows,’ Oleander said. ‘I expect you’re the welcoming party. Well then, lead on, children, lead on. The day wears on, the shadows lengthen and strange moons circle through the skies. And we have far to go.’

One of the creatures, a goatish thing wearing a peaked officer’s cap, barked what might have been an order. The pack shuffled forward warily, closing ranks about Oleander. It was no honour guard, but it would do. Oleander allowed the mutants to escort him deeper into the city. While he knew the way perfectly well, he saw no reason to antagonise them.

Their ranks swelled and thinned at seemingly random intervals as the journey progressed. Knots of muttering brutes vanished into the shadows, only to be replaced by others. Oleander studied the crude heraldry of the newcomers with some interest. When he’d last been here, they had barely known what clothes were. Now they had devised primitive insignia of rank, and split into distinct groups – or perhaps tribes. Perhaps the changeovers were due to territorial differences.

Whatever their loyalties, they were afraid of him. Oleander relished the thought. It was good to be feared. There was nothing quite like it. The beasts who surrounded him now were more human-looking. They were clad in purple-stained rags and armour marked with what might have been an unsophisticated rendition of the old winged claw insignia of the Emperor’s Children. It amused him. They likely had more in common with the men they aped than they could conceive. Both were far removed from their creator’s intended ideal.

His amusement faded as the palace at last came into sight. Its delicate tiers stretched gracefully up towards the blistered sky. Chunks had been gouged out of its curved walls, to allow for the addition of multiple power sources, rad-vents and gun emplacements. It was akin to a beautiful flower, encrusted with a bristling techno-organic fungus. Rubble had been cleared from the broad avenue leading up to the main entrance. A crude shanty town, built from debris, had sprung up around the outer walls of the ancient structure.

More than once, he saw what could only be barbaric shrines, and statues decorated with articulated bones and offerings of stitched skin and gory meat. Mutants chanted softly to these statues, and he heard the words ‘Pater Mutatis’ and ‘Benefactor’ most often. The Father of Mutants. He wondered whether the object of such veneration was pleased by the acknowledgement, or annoyed by its crudity.

Unseen horns blew a warning, or perhaps a greeting, as Oleander and his escort moved along the avenue. The wind had picked up, carrying with it the ever-present screams of the ancient dead, as well as the barks and howls of the shanty town’s debased population. Dust roiled through the air, momentarily obscuring the ruins around him. Oleander briefly considered putting his helmet back on, but discarded the idea after a moment. It was hard to sing, inside the helmet. ‘Song of my soul, my voice is dead, die thou, unsung, as tears unshed…’

Abruptly, the cacophony rising from the shanty town died away. The only sounds left were the phantom screams and Oleander’s singing. But these too faded as the sound of heavy boots crunching stone and bone rose up. Oleander could barely make out the approaching figure through the dust and the wind. He reached for his bolt pistol.

‘No need for that, I assure you.’ The vox-link crackled with atmospheric distortion, but the voice was recognisable for all that. Oleander relaxed slightly, though not completely. The dust began to clear. A large shape stepped forward.

The warrior’s power armour had been painted white and blue once, but now it was mostly scraped grey or stained brown with blood and other substances. Black mould crept across the battle-scarred ceramite plates, like oil across snow. A sextet of cracked skulls hung from the chest-plate, wreathed in chains. More chains crisscrossed the Space Marine’s torso and arms, as if to keep something contained. Like Oleander, he also wore the accoutrements of an Apothecary, though his had seen far more use, under heavier fire. A curved falax blade was sheathed on either hip.

‘Waiting for me?’ Oleander said. He kept his hand on the grip of his bolt pistol.

‘I heard the beasts howling,’ the other said. He reached up and unlatched his helmet. Seals hissed and recycled air spurted as he pulled it off, revealing a familiar, scarred face. He’d been handsome, once, before the fighting pits. Now he resembled a statue that had been used for target practice. ‘And here you are. Still singing that same dreadful dirge.’

‘No mask, no mask,’ Oleander said, finishing the song.

‘Learn a new tune,’ the other said.

‘You were never a music lover were you, Arrian?’ Arrian Zorzi had once served at Angron’s pleasure, on the killing fields of the Great Crusade. Now he obeyed a new master. Oleander thought Arrian had traded up, if anything.

Angron had been a puling psychopath even before he’d taken his first steps towards daemonhood. Worse even than glorious Fulgrim, whose light was as that of the sun. A master you chose was better than one chosen for you. At least that way, you had no one to blame but yourself.

‘Exile agrees with you, brother.’ Arrian’s voice was soft. Softer than it ought to have been. As if it came from the mouth of some inbred outer-rim aristocrat, rather than a savage draped in skulls and chains. A considered affectation. Another way of chaining the beast inside.

‘I left of my own volition.’

‘And now you’re back.’

‘Is that going to be a problem?’ He would only have time for one shot, if that. Arrian was fiendishly quick, when he put his mind to it. Another memento of years spent wading in someone else’s blood, for the entertainment of a screaming crowd.

‘No.’ Arrian’s fingers tapped against the hilt of one of his swords. ‘I bear you no particular malice today.’ He reached up to stroke one of the skulls. The cortical implants dangling from it rattled softly.

‘And them?’ Oleander said, indicating the skulls. The skulls had belonged to the warriors of Arrian’s former squad. All dead now, and by Arrian’s hand. When a warhound decided to find a new master, bloodshed was inevitable.

‘My brothers are dead, Oleander. And as such only concerned with the business of the dead. What about you?’

‘I want to see him.’

Arrian glanced over his shoulder. He looked down at his skulls, and tapped one. ‘You’re right, brothers. He’s watching,’ he said, to the skull.

‘Is he, then?’ Oleander said. He turned, scanning the desolation. When he turned back, Arrian was leaning against the archway. He hadn’t even heard the World Eater move.

‘He’s always watching, you know that. From inside as well as out,’ Arrian said. ‘Enter, and be welcome once more to the Grand Apothecarion, Oleander Koh. The Chief Apothecary is expecting you.’

CHAPTER TWO

The Grand Apothecarion

Their footsteps echoed hollowly in the cavernous spaces of the shattered palace. Oleander and Arrian walked side by side through the entry halls, past defensive hard points. Urum had come under attack more than once since Bile had established his laboratories there. The two moved in easy silence. They’d never had much to talk about, even in better times. Now, Oleander could feel Arrian surreptitiously studying him. Sizing him up for the chopping block, perhaps. Arrian had always been the most loyal of all of them to Bile’s ideal, for reasons of his own. But then, what else could one expect of a warhound?

‘New sword?’ Arrian said.

‘My last one broke.’

‘You always were quite hard on them, as I recall. A Tuonela mortuary sword. A fine weapon for a fine warrior.’ Arrian cocked his head. ‘What are you doing with it?’

‘Spoils of war,’ Oleander said. ‘I had to shoot its owner.’

‘In the back?’

‘Obviously.’

Arrian laughed. The sound put Oleander in mind of a dull blade scraping across wet flesh. The Consortium, as their master called it, had always been an uneasy alliance at best. Its members were not brothers, save in the most figurative sense – they were all Apothecaries, but from different Legions and warbands. Drawn together by a shared desire to learn more of the arts of flesh and bone, of gland and organ, from the acknowledged master. The human body was a mystery that they were all desperately trying to solve, and so they came to sit at the feet of its greatest student, and learn all that he had to teach them.

Some, like Arrian, had been here for centuries, even accounting for the way time moved in the Eye of Terror. Others stayed only for a few months, or even weeks. Some came to learn a specific lesson, others were sponges, absorbing all that their host knew. And some few learned nothing, and became a lesson themselves.

But of all of them, Arrian Zorzi had always been the most dangerous. He smiled too easily, thought too quickly, for what he was. Those pain-inducing cortical nodes had only honed him into an even deadlier predator. Oleander longed to wipe the smile off the other renegade’s face, if only to find out what was hiding beneath it. Arrian was a monster who refused to admit it, and was somehow all the more monstrous because of it. Oleander restrained the desire, with some difficulty. Renewing old grudges wasn’t why he’d returned.

He distracted himself by studying his surroundings. While the outer palace was all but empty, the inner was anything but. The diverse chambers here had once housed decadent feasts, bloody gladiatorial games and indulgent orgies. Now the labyrinthine warrens of unnatural construction were home to the various apothecaria and vivisectoria established by the members of the Consortium. The palace had become a bedlam of grotesquery, filled with the sounds, sights and smells of abomination. Screams, both human and otherwise, echoed through the vaulted corridors and along the rows of hermetically sealed operation chambers. As well as these, Oleander could hear the rattle of surgical tools, the hiss of pneumatic chem-pumps and the quiet murmur of voices engaged in debate and study.

Faces peered at him from shadowed archways, their gazes by turns curious and baleful. He had not left under the best of circumstances. Many of those who came to Urum did so seeking some form of sanctuary. A safe place to indulge in their own depravity, abetted by one whose utter corruption far outstripped their own. And some of those, like the half-men outside, even worshipped their benefactor in a way. A cult of genius had taken root here, and those who abandoned it were viewed with disdain, if not outright hostility.

Those laboratories closer to the outer palace were smaller, and the Apothecaries who had claimed them were the newest to join the Consortium. Oleander observed a cavalcade of horrors through the armourglass portholes set into the entryways. Crude surgeries and childish experiments filled these chambers. ‘To do is to learn,’ he said.

Arrian glanced at him. ‘And to learn is to know,’ he said, completing the old phrase. It was a joke, of sorts. A rationalisation for the irrational. ‘You haven’t forgotten everything you learned here.’

‘I forget nothing.’

Arrian chuckled. ‘For your sake, I hope so. You know how he likes his little tests.’

Stunted mutants hopped and crawled along the corridors, giving the two legionaries a wide berth. They wore ragged cloaks which obscured their twisted forms and hissing rebreathers. They carried equipment to the various laboratories, or else acted as surgical assistants when necessary. Oleander kicked lazily at one when it drew too close. ‘Vat-born maggot,’ he said. The creature shrank back, whining.

Arrian slid in front of him. ‘Cease. They are not yours to play with.’ His hands rested on the pommels of his falax blades.

‘It almost touched me,’ Oleander said. ‘I cannot abide being touched by something so… so utilitarian.’ He practically spat the word. The vat-born didn’t even have the distinction of being uniquely hideous. They all looked alike, sounded alike, even smelled alike. As if they had been stamped from a mould. It grated on his senses. Such banality was anathema to him.

‘And yet you frolic with the beasts outside,’ Arrian said.

‘At least they offer some variety.’ Oleander made a face. ‘I’m surprised there are any of them still left. Have you seen what they’re building out there?’

Arrian shrugged. ‘We leave them to their own devices. They’ve begun to cobble together a crude society of sorts. They have wars, sometimes. It’s entertaining, in its way.’

‘And what does the master think?’ Oleander said. ‘Is he entertained as easily as you?’

Arrian glanced at him. ‘The Chief Apothecary doesn’t think of them at all, Oleander. They’re meat, and of little use for anything save as an early warning system. Why are you back?’

‘I told you, I want to see him. And he obviously wishes to see me, else we would not be here. What about the others?’ Like any group, the Consortium had its fair share of favoured individuals. Those who had proven their use beyond a shadow of a doubt, or who were so deeply indebted to Bile that they could not refuse him. Oleander still wasn’t sure which of those described Arrian.

‘Skalagrim is leading an expedition to Belial IV – Chief Apothecary Fabius wishes to establish a second facility there,’ Arrian said. Oleander grunted in distaste. Skalagrim was a renegade twice over, and untrustworthy even at the best of times.

‘What about Chort?’ Chort took great delight in crafting new flesh-forms. Many was the warlord who had begged for a chance to hunt the inexplicable monstrosities Chort had devised. ‘And old Malpertus?’

‘Chort vanished a month ago, on some errand or other for the Chief Apothecary. Malpertus… died on Korazin,’ Arrian said.

‘Died?’ Oleander said. Malpertus’ face swam to the surface of his mind – hollow cheeks, filmy eyes and yellow teeth, worn to nubs. Malpertus hadn’t been his real name, and his armour had been scoured of all insignia. That alone had been enough to betray his true allegiances, as far as Oleander was concerned.

‘We were all very sad,’ Arrian said, sounding anything but. ‘Especially Saqqara.’

‘Saqqara is still alive?’ That was a surprise. Saqqara Thresh had led a Word Bearer kill-team to Urum. They’d been looking to deliver Bile’s head to the Dark Council for some unspecified slight. They’d failed, of course. Urum ate daemons as easily as it ate men, and Saqqara’s force had gone from impressive to pitiable in a few days. By the time the Consortium had struck, the Word Bearers had practically been begging for death.

Only Saqqara had remained sound of mind and body, thanks to his skill with daemonancy; one of the reasons Bile had decided to spare the diabolist. Daemons were a fact of life in Eyespace, and it was no more than prudent to employ the services of one skilled in the art of their summoning and banishment, however unwilling.

‘You’d be surprised at how little a man like that wants to meet his gods.’ Arrian scratched his chin. ‘We caught him trying to cut the bomb out a few months ago. He’d got all the way to the meat by the time we stopped him.’

Oleander laughed. Saqqara had been attempting to remove the chem-bomb Bile had surgically implanted between his hearts for years. When the bomb went off – it wasn’t a question of if – Saqqara’s body would be reduced to bubbling protoplasm. It was the most obvious of the modifications Bile had made to the Word Bearer. The Chief Apothecary claimed to have implanted a thousand and one contingencies into his most reluctant servant. Saqqara occupied himself trying to discover them, when he wasn’t attempting to stir up a rebellion amongst Bile’s followers.

‘What of Honourable Tzimiskes?’ Oleander asked as they ducked beneath a cracked archway and entered what had once been a garden. Now the only thing that grew here was a peculiar species of red weed. Beside the crumbled remains of what had once been a fountain stood a sextet of towering shapes, their once vibrant purple colours dulled by grime and neglect to a muddy bruise. Castellax battle-automata, he realised, the shock-troops of the Legio Cybernetica. Servo-skulls hovered about the war machines like flies, their auspex humming.

‘Does that answer your question?’ Arrian said. Oleander saw two familiar figures standing among the battle-automata. Both were legionaries, but one’s power armour was an older mark, and heavy. It was daubed in drab colours, save for the gleaming stylised iron skull emblazoned on one shoulder-plate. Tzimiskes Flay was an exile from Medrengard, as far as Oleander knew, though there was some debate on that score, as well as a substantial amount of wagering. Nonetheless, the Consortium welcomed all practitioners of the arts of the flesh, whatever their origins.

As Oleander and Arrian drew close, one of the Castellax took a halting step forward and trained its bolt cannons on them. The barrels bobbed and rotated as internal targeting arrays calculated distance. Arrian slammed a forearm into Oleander’s chest. ‘Don’t move. They’re overeager. Endorphin pumps wired to their firing mechanisms, I think. Tzimiskes – brother – call your creature off.’

Tzimiskes stared at them for a moment, as if considering the possibility of a live-fire exercise. Then, with a shrug, he opened the chassis of the agitated war machine, revealing the worm-pale features of a semi-human face within. The face was nestled in a web of wires, and its mouth opened and closed soundlessly as Tzimiskes fiddled with the internal mechanisms. It squalled in protest. The robot sank down to one knee and lowered its guns as the thing inside moaned petulantly.

‘Slave-brains,’ Arrian said. ‘He’s been growing them in his laboratorium, in the eastern wing of the palace. Better reaction times than standard battle-automata, or so some of the others claim.’

‘Ever the artisan, my brother,’ Oleander said, loudly. Tzimiskes turned and cocked his head, perhaps in greeting. Maybe just in acknowledgement. If he was surprised to see Oleander, he gave no sign. Not that Oleander had expected any sort of welcome.

‘You’re back,’ the other renegade said. ‘I thought you were smarter than that, Oleander.’ Saqqara Thresh looked much as Oleander remembered – pinch-faced and fang-mouthed. His crimson power armour had seen better centuries. There were few places on it not covered in lines of cramped, curling script, or adorned with blasphemous iconography. The lines of script were lifted from the ritual texts, hymns and cult doctrine that Saqqara and his brothers considered a suitable replacement for common sense. Suture scars marked his bare flesh, following the curve of his skull and the line of his jaw. Bile had surgically inserted numerous control implants, obedience nodes, and at least one miniaturised fragmentation detonator in the Word Bearer’s brain matter and jaw muscles.

‘And I thought you’d have blown yourself up by now, Saqqara. Looks like we were both mistaken. Still hectoring poor Tzimiskes, I see.’

Saqqara smiled. ‘We were discussing the seventh and fifteenth tracts of Grand Apostle Ekodas, in his third address to the Dark Council. Tzimiskes is quite devout, for an Iron Warrior. Something you would know nothing about.’

Oleander looked at Tzimiskes. As ever, he did not reply. To the best of Oleander’s knowledge, the Iron Warrior had never spoken.

‘Our silent brother is polite, if nothing else,’ Arrian said.

‘Another thing you would know nothing about,’ Saqqara said. Arrian smiled and stroked his skulls. Saqqara met his gaze and held it. There was no faulting the Word Bearer’s courage.

‘Come, brother. I have come a long way, and time is short,’ Oleander said, breaking the tension. ‘Is he still trying to provoke the others?’ he asked, as Arrian led him out of the garden. Inciting treachery was Saqqara’s sole avenue of resistance. Oleander suspected that Bile kept the Word Bearer around as much to weed out the foolishly disloyal as to summon the occasional daemon.

‘He’s been working on Tzimiskes for a while now. Like the proverbial bird and the mountain,’ Arrian said.

‘Probably hoping our silent brother will snap and unleash a horde of mechanical murder-machines on the rest of you,’ Oleander said. The inner palace was much as he remembered. The broad corridor, with its titanic pillars reaching up into the shadowed reaches of the roof above; the scattered remains of ancient statues; the faded murals depicting scenes from the history of Urum’s former rulers. There was a sense of sadness here, as much as one of horror. Broken grandeur was still grandeur.

Oleander stopped before one of the murals. He studied the entwined figures, trying to discern where one ended and the others began. There were stains on the wall. Some old, most new. Blood and other substances. Oleander spread his fingers. The walls of the palace spoke, sometimes. When the wind was high and sand scoured the city. If you listened, you could hear the songs, the moans, the screams of those forgotten revelries. But he heard nothing now.

‘They’ve been quiet, since you left,’ Arrian said.

‘I was the only one who appreciated them,’ Oleander said.

‘We are here to learn the secrets of life, not listen to the complaints of the dead,’ the World Eater said. ‘You might have retreated into the past, but the rest of us have always moved ever forward.’

Oleander laughed. ‘There is no “us” here. Only him. The rest of us are nothing more than raw materials yet to be rendered down.’ He looked at Arrian. ‘What has he taught you since I left, Arrian? What secrets have you learned?’

‘None I’ll share with you,’ Arrian said. His hands fell to the hilts of his blades. ‘Though I’d be happy to show you, if you wish.’

Oleander shook his head. ‘Still loyal to a madman, after all these years.’ He looked back at the mural. ‘I wonder if that’s why he keeps you around. For a surgeon, you make a wonderful butcher, and you have little interest in building monsters. And yet here you are, as in favour as ever. Always at his beck and call.’

Arrian said nothing. Trying to goad him was a fool’s game, although Oleander couldn’t help but try. It was like watching a tiger asleep in a cage, and knowing it dreamed red dreams. ‘Oh the beast I could make of you, brother,’ he said softly. ‘What beautiful horrors you would wreak then.’

‘No, brother. Never a beast. Never that,’ Arrian said. His voice was tight, and his face might as well have been a slab of stone. His hands twitched slightly, where they rested on the hilts of the falax blades. The chains wrapped about him creaked slightly, as if they were on the verge of snapping.

The moment passed. Oleander inclined his head. ‘As delightful as this has been, I am ready to see him. Take me to him, Arrian.’

‘That is what I have been doing, brother. He is in his laboratorium, hard at work.’

‘On what?’

‘Himself,’ Arrian said. He turned away. Oleander hesitated a moment, and then followed. As they drew closer to the heart of the palace, the temperature dropped substantially. Cooling units chugged loudly in out-of-the-way corners, filling the corridors with a chill, counterseptic mist. Vox-casters and pict-recorders hummed and whirred atop support pillars and along the walls. Nothing went unseen or unrecorded in the Grand Apothecarium. Monsters howled somewhere in the dark. Once, Arrian waved Oleander to silence as the way ahead was suddenly blocked by indistinct shapes. They padded forward through the mist, eyes gleaming gold. The World Eater raised his hand and let the assortment of medicae devices built into his vambrace skirl to life. The shapes scattered as silently as they had appeared.

‘What were they?’ Oleander asked.

‘For now – test cases,’ Arrian said. ‘Later – who knows?’

‘He’s letting them run loose now? In my day, he used to seal things like that away, in one of the outer rings.’ The true size of the palace had always been a matter of some debate. It was a labyrinth of concentric rings, both larger and smaller than it appeared from orbit. Whole squads of would-be explorers had vanished into its outer rings, never to be seen again.

‘We still do. Sometimes they get out. They come back… changed,’ Arrian said. ‘He finds it interesting. So he lets them roam, and we study them, when we’re lucky enough to capture one.’ He cocked his head. ‘That doesn’t happen often, sadly.’ He showed his teeth in a broken smile. ‘They are getting smarter, out there in the dark.’

Oleander rested his hand on his bolt pistol, suddenly alert. It was a welcome feeling. He had missed this place. The sense that a new horror lurked around every corner. One never quite grew used to it. Intoxicating in its way.

The rattle of weapons caught his attention. They had come to a reinforced doorway, where several men and women stood on guard. They were clad in grimy fatigues and battered carapace chest-plates. Equipment belts and ammunition bandoliers completed the image of a rag-tag planetary militia. But these were no normal humans. The muscles in their arms and necks bulged with almost Astartes-like thickness, and there were series codes tattooed on their cheeks. They stank of chemicals and other, less identifiable things.

Gland-hounds. The New Humanity, as designed by Fabius Bile. Stronger, faster, more aggressive than the brief sparks that sheltered in the shadow of the Imperium. The first generation had been born of partial gene-seed implantation. Those first few crude attempts had become more refined over time, as the master had devised his own, lesser form of gene-seed. One which was not so likely to kill its host out of hand.

They came alert instantly. There was a disconcerting intensity to their blank gazes – as if he were some large bovid who had wandered unknowing into the midst of a carnosaur pack. It had been a long time since anything had looked at him that way, and he shivered in delight. ‘They say, in the lands of milk and sorrow, that those pale echoes of our brothers now gone know no fear,’ he said to Arrian. ‘It saddens me to think of it.’

As he spoke, one of hounds stepped forward, setting herself between them and the doorway beyond. She crossed her muscular arms, and gazed steadily at them. ‘Igori,’ Arrian said. There was an odd sort of respect in his tone, Oleander thought. He bridled at it. Arrian was free to consider the creature his equal, but Oleander was under no such obligation.

‘You’re new,’ Oleander said, looking down at the woman – Igori, Arrian had called her. He sniffed, and grimaced. ‘But I can tell you’re one of his. I can smell it from here.’

Igori said nothing. Her face was square. It might as well have been chiselled out of marble. Everything about her was perfect. Too perfect, too symmetrical. As if she were nothing more than a machine of meat and muscle.

‘Where is he? Take me to him,’ he said.

Most humans were frightened of his kind. Even the strongest of them were but fragile things compared to a Renegade Space Marine, especially one hardened by centuries of living in the Eye. But Bile’s Gland-hounds had no fear. Or, rather, they didn’t express it in the same way a normal human did. At his tone, her hand fell to the hilt of the blade sheathed on one hip. The other hounds tensed, ready to leap at the slightest provocation.

Oleander grinned. It had been an age since he’d carved the guts out of one of his old teacher’s pets. They took a pleasingly long time to die. He reached for the hilt of his own sword. He stopped as something tapped his shoulder-plate. He turned, and saw the flat of one of Arrian’s blades laying across the ceramite.

‘I wouldn’t, brother,’ Arrian said, softly. ‘She is his favourite, currently. Look at that necklace of baubles she wears. What do you see?’

‘Teeth,’ Oleander said.

‘Whose?’ Arrian’s voice was a rasping purr.

‘So long as they aren’t mine, I don’t particularly care,’ Oleander said.

‘You were never very observant.’ Arrian leaned close. ‘Space Marines, brother.’

The Gland-hounds were built to hunt Space Marines. Or, rather, their gene-seed. One on one, they were no match for their prey, but in a pack they could pull down even the most frenzied of Khorne’s chosen. Bile doted on them. He even gave them as gifts, sometimes, when the mood struck him. They were prized by those for whom limited stocks of gene-seed were still an active concern, such as the Iron Warriors.

Oleander shrugged Arrian’s blade away. ‘I don’t care where she got them. No human threatens me and lives. I’ll make a fine robe from her flesh.’

‘You will not,’ Arrian said. ‘She is not yours to kill.’

Oleander nodded obligingly. He could resist the pull of the moment no longer. ‘No. I suppose not.’ He spun, slapping Arrian’s blade aside, and leapt on his fellow Apothecary. They crashed together and Arrian stumbled back. Oleander whipped his sword free of its sheath, just in time to parry a killing blow from the falax blade.

‘Oh, how I have dreamed of this,’ he said. The Gland-hounds had retreated, unwilling to get between the two. Oleander ignored them. Fierce as they were, they were outmatched and knew it. ‘I’ve owed you a humbling for some time, World Eater.’

Arrian stepped back, arms spread. ‘Well, come then, brother. Come and take your due.’

Oleander lunged. Their swords met, separated and met again. The hilt twisted in his hands as he spun, leapt, and lunged again. Though he fancied himself a swordsman, he knew that he was, at best, serviceable. It was an affectation, and one sadly common to the warriors of the Third. They all desired to be a Lucius, form and function combined in lethal harmony. Oleander’s Apothecary training gave him an edge in most duels – he knew exactly where to strike to cripple, or to kill. Places most warriors never even thought of.

But Arrian knew those places as well. And he was a better swordsman. He’d drawn his second falax blade and he slapped them together. ‘It’s been some time since I’ve been able to practise on something other than mutants,’ he said. ‘I suppose I should thank you.’

Oleander bared his teeth and stepped forward, sword whistling out. Arrian caught the blow on his blades and forced the sword down. ‘Do you remember how we used to spar for the privilege of assisting him, Apothecary Oleander? First blood only, for we knew our value. But these days, your value is greatly lessened.’ He held Oleander’s blade down, trapped against the floor. Before Oleander could wrench it free, Arrian lunged forward. Their heads connected, and Oleander lost his grip on his sword.

He stumbled back. Something struck the back of his legs. Already off balance, he fell to one knee. The tip of a blade pressed against his jugular. Igori looked down at him. He made to strike her, and she retreated, whipping her knife away from his throat. He forced himself to his feet, ready to leap on her. Before he could, Arrian kicked his sword towards him.

‘Pick it up,’ the World Eater said. ‘Let us finish, before you find a new partner.’

Oleander hesitated, and then knelt to scoop up his sword. As he stood, the vox array mounted on the wall above crackled suddenly. ‘Be at peace, all of you. Sheathe your blades, Arrian. Step aside Igori, there’s my loyal child. I have been waiting on our guest for some time, and would delay our reunion no longer. Apothecary Arrian… assemble the others in the auditorium. I am sure that they will wish to hear what has compelled our prodigal brother to return.’

The voice echoing from the vox was that of the former Chief Apothecary and Lieutenant Commander of the Emperor’s Children. The being known variously as Primogenitor, Clonelord and Manflayer. The creature Oleander Koh had once called master…

Fabius Bile.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...