INTRODUCTION

I swore I would never write a novel.

My first allegiance, my deepest loyalty, was to short fiction—the only species of confabulation that grants you total freedom to mess around. I was a natural short story writer who loved to explore a concept to the fullest in a few thousand words and then flit to the next tiny epic. Novels felt like such a serious commitment that I would never dare to try such headlong flights of fancy in them, and I had way more fun soaring (and occasionally crashing) through world after world, one story at a time.

After all, writing short fiction was the reason I’d bailed out of my first journalism career.

Years ago, I was working a soul-crushing job at a local newspaper, where I spent most of my time in a cubicle, freaking out into a telephone. My boss was an easygoing sadist who encouraged me to tell potential sources that I would lose my job if I didn’t get a decent scoop soon. (He assured me I wouldn’t be lying if I said that.)

I got home from work feeling both drained and freaked out, with no mental energy left for my own writing projects.

Every day at lunchtime, I haunted a newsstand with shelves full of science fiction digests, literary magazines, and other fiction mags. I read every kind of yarn there was and reveled in all the changes a skilled writer could take me through in just a few pages, and I daydreamed about seeing my name on one of those covers.

Then I discovered something that changed my life: a thudding great hardcover that listed every market that published science fiction and fantasy short stories, along with advice on how to break in. I sat in my cubicle, when I was supposed to be calling people and telling them about my precarious employment situation, and pored furtively over the introduction, which promised, “You can get rich writing science fiction and fantasy these days.” I immediately quit the newspaper, took a much lower-stress day job, and started cranking out strange yarns with stars in my eyes.

In my first decade of writing short fiction, I racked up over six hundred rejections and published ninety-three stories, mostly in small markets that no longer exist. Not to mention, a few dozen of my stories never found a home. Every day, when I finished work in my lower-stress day job, I walked to the nearest Caribou Coffee, where I guzzled turtle mocha (the drink of champions!) and wrote the sickest fever-dreams I could imagine, full of space theologians, lesbian dung beetles, and disposable genitalia.

I toiled alone on those first ninety-three short stories, but I was always surrounded by friends and fellow travelers. I talked pretty much every day to my best friend and mentor, the late horror writer D. G. K. Goldberg: comparing notes, trading critiques, and commiserating over the latest form letter. I also joined a ton of writers’ groups, read at open mics, haunted convention bars, and lurked on forums like SFF.net. The whole process of writing and selling short fiction became a shared experience, and whenever I made it into print, I got to bond with everyone else whose name appeared in the same TOC, or table of contents—we were “TOC-mates.”

My rejections were a badge of honor. I kept a document with a careful record of where every story had already gone and which markets I hadn’t tried lately, and I also noted which editors had written a personal response. At the bottom of that document, I wrote, “Rejections should be welcomed. There is nothing more joyful and optimistic than the act of putting a story in the mail, especially if that story has already come back once or twice.” (Or, more often, a dozen times.)

Online, a bunch of us parsed rejection letters like the entrails of a freshly slaughtered goose. One magazine allegedly used various shades of paper stock, depending on how good your story was. Another editor was rumored to use different Word macros, and you could tell how much he’d liked your story by whether his response employed the word “sadly.”

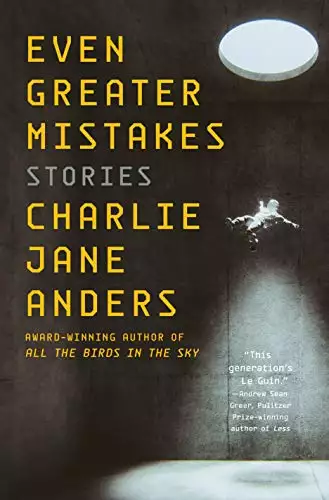

I made all kinds of bargains in my head with the universe: I would give up turtle mochas, I would stop jaywalking, if I could just get one story into a pro market—let alone one of the “year’s best” anthologies. And my ultimate dream? Was that I would have a honking big book like the one you’re looking at right now, made up of nothing but my own stories.

Writing short stories gave me tons of practice with beginnings and endings, not to mention world-building and character creation—but they also let me work with scores of editors, who collectively mentored and shaped me. I owe a huge debt to the crew at Strange Horizons, who published two of those ninety-three stories but also gave me feedback on countless others. Sometimes an editor would take the time to talk through why a story wasn’t working, or offered me advice on how to remove some of my inevitable clutter and deadweight.

Not all of these interactions were fantastic, for sure. One lit-mag editor spent an hour on the phone giving me genuinely helpful thoughts about my story—mixed with transphobic observations about my main character.

Another lit-mag editor responded to a submission by saying that he only liked one sentence of my story. Would I take that one sentence, which was about a minor supporting character, and build a whole new story around it? I elected to think of this as a fun challenge, so eventually I produced a whole new story that contained that one sentence. The editor wrote back and said that he now liked two sentences: the one he’d originally liked, plus a new one. He asked me to write a third story from scratch, using those two sentences. After some hesitation, I went ahead and did so, and luckily, the third time was the charm.

At some point, I started reading slush for a few different magazines, and that was also invaluable training in how to think like the editors I was sending my work to. I found out the hard way that when you have hundreds of submissions to get through, you make a lot of snap judgments after the first couple pages, and it’s on the writer to give the editor (and reader) a reason to keep reading. In one case, I volunteered for a magazine that had several crates full of unread subs, and I dug out a story that I had sent them a few years earlier. I reread my own piece, saw that it was completely wrong for the magazine, and had the dubious pleasure of sending myself a rejection letter.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved