- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

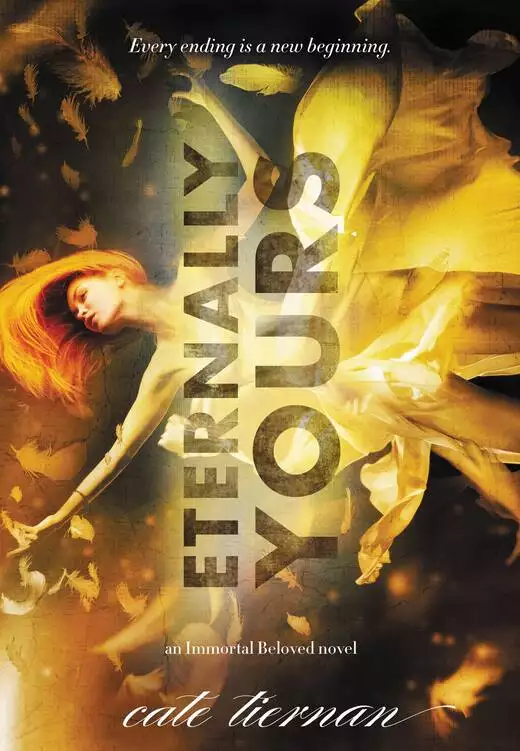

Synopsis

After 450 years of living, Nastasya Crowe should have more of a handle on this whole immortal thing.... After a deadly confrontation at the end of Darkness Falls, the second Immortal Beloved novel, Nastasya Crowe is, as she would put it, so over the drama. She fights back against the dark immortals with her own brand of kick-butt magick...but can she fight against true love? In the satisfying finale to the Immortal Beloved trilogy, ex-party-girl immortal Nastasya ends a 450-year-old feud and learns what ""eternally yours"" really means. Laced with historical flashbacks and laugh-out-loud dialogue, the Immortal Beloved trilogy is a fascinating and unique take on what it would mean to live forever."

Release date: December 3, 2013

Publisher: Poppy

Print pages: 464

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Eternally Yours

Cate Tiernan

Vali! Vali! Where is the girl?”

I heard my employer’s voice and scrambled up from the storage cellar.

“Here!” I said breathlessly, setting the heavy box of gold thread on the counter. The wooden steps to the cellar below the shop were barely more than a ladder; I’d had to hold the box with one hand while the other kept me from pitching head over feet. In time I would become as nimble as a mountain goat, but I’d been here only a month and these stairs were, even by Scandinavian standards, steep and narrow. Factor in the long skirts and petticoats and you had potential disaster in the making.

My employer, Master Nils Svenson, gave his customer a smile. “Vali is new here; she’s still learning the stock.”

I made a little curtsey, keeping my eyes down.

“She’s doing very well, though, aren’t you, dear?” Master Svenson nodded at me approvingly, then turned his full attention to the man who was deep in the throes of deciding whether large ruffs were truly going out of fashion or not.

I took a feather duster from my apron pocket and began to dust the bolts of fabrics lining two walls. My master was one of the most sought-after tailors in Uppsala, known to have the finest fabrics: finely woven wools, smooth to my hand and dyed in deep jewel tones; plain and colored linen in various weights, from moth-wing gauzy to the heavy, sturdy cloth for breeches and bodices; unbelievably fine silk from the Far East in bright, parrot colors that were completely exotic and out of place in this country in November.

The silver bell over the shop door tinkled, and a very elegant woman came in, her hat trailing a turquoise ostrich plume that I knew cost as much as what I earned in six months.

“Hello, my dear,” said the man, turning and lightly catching the woman’s gloved hand to kiss. “I apologize for being late.”

“I’m not inconvenienced in the least,” she said graciously. “You finish your business.” She seemed to glide across the shop on fine kid shoes that made barely a sound. Moments later she stood near me as I flicked the duster and tried not to stare at her beautiful storm-gray cloak, chain-stitched all over with black flowers.

“What exquisite fabric,” she murmured, gently touching a peach-colored watered silk, its silver-thread embroidery making it heavy and stiff. She turned to her husband. “My dear? You really should have a waist—”

I don’t know why she looked at me just then, but she did, her clear blue eyes skimming absently across me and then sharpening and locking on my face like a magnet. She stopped in midword, her eyes wide. Her hand gathered a bit of silk and held it, as if without it she would fall down.

“Yes, my dear?” her husband said.

She let go of the silk and gave a shaky smile. “One moment.” She gracefully turned her back to the two men and looked at me again.

“You,” she said in a voice too low for them to hear.

“Yes, mistress?” I asked, concerned. Then—I don’t know how to describe it. I still can’t. I don’t know how we know or what it is. But I met her eyes, and there passed between us an instant of recognition. My mouth opened, and I almost gasped.

We had seen each other for what we were: immortal. I hadn’t met another person like me in three countries, eight cities, and almost fifty years.

“Who are you?” she whispered.

“My name is Vali, mistress.”

“Where are you from?”

The decades-old lie came easily to me. “Noregr, mistress,” I murmured, hoping that there were in fact immortals in Norway. I hadn’t met any when I lived there.

“My dear?” her husband called.

With a last penetrating look, the woman left me and joined her husband. Soon they went out into the dark, cold afternoon—it was only three thirty, but of course the sun had set already, this far north.

I stood still, my mind turning wheels, until I realized Master Svenson was looking at me. I started busily dusting again.

The next day my master called me over from the glass-fronted display of silk ribbons that I’d been arranging.

He was wrapping something in brown paper, folding it neatly and then tying it with waxed twine. “I need you to take this to Mistress Henstrom,” he said. “She’s requested several cloth samples.” He took up his pen, dipped it in ink, and wrote her street and house number on the paper in his educated, slanty script. “Make haste, Vali. And here—buy yourself a bun on the way back.” He handed me a few copper coins.

“Thank you, sir,” I said. He was a genuinely kind man, and working for him hadn’t been at all bad so far.

I retucked the scarf I wore always, pulled on my own loden-green rough-wool cloak, and hurried out. This Mistress Henstrom lived about a thirty-minute walk away. I dodged street filth, horses, and people crowding the high street’s shops, and was glad again that I lived in a town and no longer in the countryside. Uppsala was by far the biggest town I had lived in since Reykjavík. In the countryside, night closed in on you like a bell placed over a light, silent and grim. Here even at midnight you could occasionally hear the clopping of horseshoes on the cobbles, a baby’s wail, sometimes the off-tune and bawdy singing of men who’d drunk too much. And here, in this town, lived at least one other immortal.

The streets twisted and turned, and more than once I had to backtrack and take a different route. I walked as fast as I could, mostly to keep warm, but the damp, misty chill slipped under my cloak and through my ankle-high boots. By the time I found the correct house number, I was chilled down to my fingernails and shaking with cold.

The house was large and fine, made of brown brick with other colored bricks set into a pattern, and it had a false front with ziggurats. It was four stories high, with the entrance up a tall flight of stairs. I struck the lion’s-head heavy brass knocker several times. The black enameled door was opened almost immediately by a big, round woman wearing a spotless white apron. She had the reddened, work-roughened hands of a servant but also an unmistakable sense of importance. So the head housekeeper, maybe.

“I’m from Master Svenson’s shop?” I said. “With fabric samples for the mistress.” I held out the package for her to take, but she opened the door wider.

“She’s waitin’ on you in the front drawing room.”

“Me? I’m just the shopgirl.”

“Go on then.” The housekeeper nodded toward a double set of tall, paneled doors painted dove gray.

Inside, a woman sat before a white marble fireplace carved with fruit and garlands. Blue and white tiles with ships on them surrounded the firebox, and I wanted to kneel down and look at each tile, enjoying the fire’s delicious warmth. Instead I stood uncertainly in the doorway, and then the woman moved and I saw her face. My heart sped up: It was the woman from the shop the afternoon before. The immortal.

“Oh, good—the samples from Master Svenson,” said the woman, her voice smooth and modulated, the accent refined. “I need you to wait, girl, while I look at them. Then you can directly return my choice to your master.”

“Yes, mistress,” I said, bewildered.

“Thank you, Singe,” she said to the housekeeper, and the woman reluctantly backed out, clearly curious and disapproving of a shopgirl in the fine drawing room.

When the door had quietly clicked shut, Mistress Henstrom beckoned me closer. “Forgive the deceit, but I couldn’t call on a shopgirl,” she said in a low voice, and I nodded. “You said you were from Noregr?”

I nodded again. “And you, mistress—where are you from?” I asked boldly.

“France,” she said. I knew so little about immortals then that I was shocked. Were there immortals all over? In every other country?

I’d been in my early twenties when I was first told what I was. I hadn’t known it before then. After all, I’d seen my whole family slaughtered in front of me; they had died, and so, clearly, I could die also. But after the death of my nonimmortal first husband when I was eighteen, I’d made my way to Reykjavík and become a house servant to a large, middle-class family. I learned that they too were immortal. The mistress there, Helgar Thorsdottir, had first instructed me about our kind. At the time I was actually young, so the concept of going on endlessly had no meaning for me.

That had been fifty years earlier. As time passed, first slowly and then more quickly, it started to become real for me: to look into a piece of shined metal or the occasional real looking glass or the still water of a pond or puddle, and see the same me. Decade after decade. My skin was unlined; my hair, though light enough to be almost whitish, had no gray of old age. I was the same, always.

“How old are you, my dear?” Mistress Henstrom asked. She neither asked me to sit down nor offered me refreshment; I was just a shopgirl.

“Sixty-eight,” I said faintly. And still looked barely sixteen.

“I’m two hundred and twenty-nine,” she said, and my eyes widened. She laughed. “Surely you’ve met people older than I.”

I didn’t know how old my parents had been. I wasn’t sure how old Helgar or her husband had been, though from things she’d said she seemed about eighty. Back then. So she would be about 130 now.

“I don’t think so. I haven’t met many others like us.”

“But my dear, we’re everywhere!” She laughed again, and a small spaniel I hadn’t seen before came out from under her chair and jumped on her lap. She stroked its silky head and preposterous butterfly ears. “France and England. Spain. Italy. Here in Swerighe,” she said, gesturing out the window.

I waited for her to say “Iceland,” because that was where I’d been born, but she didn’t. I hadn’t been to any of those other countries, but that one instant, that moment, stood out so sharply against countless moments, because right then I knew that someday I would. The thought caught my breath, opening up a future I had never contemplated. In fifty years, the idea of being something more than a servant or shopgirl or wife, the thought of living somewhere besides these northern countries, had been a dream so without form that I had never grasped it.

Likewise, questions I hadn’t asked Helgar, things I’d wondered about, uncertainties that had simmered in my brain for years now boiled to the surface, and I could hardly get the words out fast enough.

“Do you know many other—people like us?”

Mistress Henstrom smiled. “Yes, of course. Quite a few. Certainly the ones who live in Uppsala—which was why I was so surprised to come across one I’d never seen.”

“Your husband?”

“A mortal, I’m afraid. A dear man.” Sadness swept over her lovely, porcelain face, and I understood immediately that one day he would die, and she wouldn’t.

“Are all the ones you know like you?” I waved my hand at the damask wallpaper, the furniture, the house. I meant rich, fancy.

She tilted her head to one side, looking at me. “No. We’re at all classes of society, at each level of birth, education, breeding.”

I’d been born to wealthy, powerful parents. We’d had the biggest, most luxurious castle in that part of Iceland—made of huge blocks of stone with real glass in the windows; at least fourteen rooms; walls hung with tapestries; servants, tutors, musical instruments; even books. When I lost my childhood, I’d lost everything about it.

“The nature of the thing is,” Mistress Henstrom said, “that when one lives quite a long time, one has quite a lot of time to fill. With educating oneself, in whatever way you can. With meeting people—influential people. With taking a small occupation and being around long enough for it to grow. Money grows over time. Or it does, at least, if you’re not silly about it.”

“I don’t have any money.” I hadn’t meant to say that, but I had absently given voice to my thoughts. I blushed because it must have been glaringly clear that I didn’t have money.

Mistress Henstrom nodded kindly. “Have you never been married?”

“Twice. But they had no money, either.” I didn’t want to think about them, not the sweet, uneducated Àsmundur I was married off to when I was sixteen, or the awful man I’d thought I could make a life with, some forty years later. They were both dead, anyway.

“Perhaps you married the wrong men.” Mistress Henstrom wasn’t being sarcastic—it was more like a suggestion. She waved her hand toward the room, much as I had done. “I have money of my own, but I also take care to marry wealthy men. And when they die, their money becomes mine alone, do you see?”

I gaped at her. “Do you mean… I should try to marry a wealthy man?”

“I think marrying poor ones did nothing to advance your position,” she said, stroking her little dog. “You have a lovely face, my dear. With different clothes, a hairstyle au courant—you could catch the eye of many a man.”

“I have no family, no connections,” I sputtered. “I’m an orphan, with nothing. Who would want to marry me?” Not to mention I never wanted to get married again.

Again Mistress Henstrom tilted her head to one side. “My dear—if I told you I was the fifth daughter of a wealthy English landowner, how would you determine it was true? The world is so big—there are so many people. No one knows them all. Letters, inquiries, take months and months. Create a family for yourself, a history, the next time you’re scrubbing a floor… or dusting bolts of fabric. Then be that person. Introduce yourself that way. Become a new person, as you’ve no doubt done before—don’t just be the same person with a new name.”

Her words tore through my brain like a comet, leaving room for new ideas, new concepts. Then my limited reality set in again. My hands plucked at my rough cloak, my plain skirt with its muddy hems. It was all too much. I didn’t know where to start. It was frightening. “I don’t—” I began.

Mistress Henstrom held up her hand. “My dear—it’s November. Stay at Master Svenson’s while you think of who you want to be, if you could be anyone—anyone at all. I’ll send for you in March.”

“Yes, mistress,” I said, overwhelmed and scared and… exhilarated.

And in March Mistress Henstrom did indeed send for me. I left Master Svenson and took the money I had scrimped and saved in the last six months and went to the Henstroms’ country house, a good ten miles out of the city. Her personal seamstress was there, and under the lady’s direction, three new dresses were made for me, indulging my particular whim of keeping my neck covered. They were much fancier and grander than anything I’d had before, but not so fancy as to arouse curiosity.

As I looked at myself in the mirror, my sunlit hair coiled in complicated braids, my blue dress so much nicer than anything I had owned since I was a child, I met Mistress Henstrom’s—Eva’s—eyes as she smiled with approval.

“May I ask…” I began hesitantly.

“Yes?”

“May I ask why you’re doing this for me? It will likely be years before I can pay you back.”

A thoughtful look came over Eva’s face. “Because… more than a hundred years ago, I was very like you. Twice the age you are now but no further advanced. I was ignorant, with no dreams for the future. And then I met someone. And she—took pity on me. She simply wanted to help me. She was the oldest person I had met—well over six hundred then.” Mistress Henstrom smiled, somewhat wistfully. “Anyway. She did for me much the same thing that I’m doing for you. I’ve always wanted to help someone myself, as a way of paying her back.” Another gracious smile. “This is my good deed. Take it and enjoy it, my dear.”

A lot happened after that, up and down, but a mere twenty-eight years later I was Elena Natoli, middle-class owner of a lace shop in Naples, Italy. I could have been much richer, with a much more leisurely lifestyle, but I just couldn’t bring myself to marry again.

I’ve never again seen the woman who called herself Eva Henstrom back in the early sixteen hundreds. If I did, I would thank her. She changed the course of my life, the way a storm can make a river jump its banks and surge ahead.

WEST LOWING, MASSACHUSETTS, USA, PRESENT

Okay, raise your hand if you’ve ever (1) dropped food or ice cream or a drink in front of (or on) someone; (2) realized you had a big stain on your clothes and it has apparently been there all day and people must have seen it but no one said anything (extra points if it’s related to a female cyclic event); (3) realized after an important dinner with someone that you had a big crumb on your lip and that’s what they kept trying to subtly signal you about but you didn’t pick up on it; (4) mispronounced an obvious word in front of a bunch of people.

I could go on. The point is, those kinds of things happen to everyone. I bet you’re still upset or embarrassed about it, right?

Well, you can freaking get over your lame-ass, sissy-pants, drama-queen self.

When you’ve run away from people who were only trying to help you; taken up with a former friend who everyone (including yourself) knew was bad news; hung out with him even as he showed signs of being certifiable; and then witnessed his complete meltdown, which, unlike some meltdowns, did not simply involve quaintly taking off his clothes and dancing in a public fountain, but instead featured huge, dark, horrifying magick, kidnapping, dismemberment, and death—well, when you’ve done that and then gone back to the people who were only trying to help you… you call me, and we’ll talk. But until you’re there, I can’t deal with whatever pebbles you’ve got in your shoe today.

“Nas? Nastasya?”

I blinked, focusing quickly on the face of one of my teachers, Anne. Her round blue eyes were expectant, her mink-brown hair in a shiny bob above her shoulders.

“Um…” I fiddled with the scarf around my neck. What was her question again? Oh. Right. “Marigold,” I said, naming the familiar orange flower on the card Anne was holding up. Flash cards, designed to help us students learn the endless facts about Every. Single. Thing. in the physical, metaphysical, and spiritual world. For starters.

Next to me, Brynne uncrossed her long legs under our table and recrossed them. I could feel her vibrating with the urge to jump in—she knew way more than I; everyone here did—but she managed to keep her mouth shut.

“Properties?” Anne was not as patient as River, and we were both starting to chafe at spending so many hours together, trying to funnel knowledge into my brain as fast as possible. I hadn’t been doing too badly—I was willing to learn—but today, focusing seemed out of reach. My cheeks started to heat as the silence swelled to fill the room. I was skin-tinglingly aware of Reyn, sitting silently next to Brynne, and Daisuke, who was studying by himself in the corner. Defeat was imminent: Searching my brain for facts about marigolds was like running around trying to catch lightning bugs. Turbo-charged lightning bugs. On coke.

“They’re used extensively in… Thailand and India, for religious purposes,” I said, trying to save face. I hated looking stupid, though by now it should feel as natural as breathing. But Reyn was here, and I hated, hated, hated looking stupid in front of him, of all people.

“Yes?” Anne said, prompting me.

Images flashed through my mind—wheeled wooden carts piled with musky-smelling bright flowers lining street markets in Nepal. No doubt they still did that today, but the memory I had was from the late eighteen hundreds. Going through Nepal on my way to Bombay to catch a merchant ship to England. And right now, let’s all give props to the Suez Canal for chopping a good four, five months off that whole journey. Who’s with me?

“Nastasya.” Anne sighed and brushed her hair off her forehead. “It would help you to know things like this.”

“I know,” I said, trying not to cringe as I heard Reyn shift in his seat. “I want to. I know I need to. It’s just—my head is really full of stuff already.”

I mean, obviously, right? Four hundred and fifty-nine years’ worth of stuff. Identities, adventures, lifetimes and lifetimes lived, each one as full as the last. Part ’n’ parcel of the whole immortal gig.

Brynne was now wiggling like a greyhound that had spotted a rabbit.

“Okay,” I said briskly, sitting up straighter. I knew this. I’d learned it a million times. “Okay, mainly used for… protection. And strength. Like to strengthen your heart or protect you from evil. Oh.”

The point of learning about the marigold sank in, and I realized that it, along with a daunting number of other things (like frankincense, fleabane, vervain, nettle, iron, and onyx, to name just a few), was intended to help me protect myself from evil. Some people try not to catch colds. I try not to attract ancient evil to me. It’s all relative.

Ancient evil. How odd that it actually exists. But it does. And my most recent brush with it, the whole horror show in Boston with my ex-bestie, Incy, had demonstrated with searing clarity how inadequate my mastery of magick was. If I’d known more that night, I might have been able to save Katy and Boz. Might not have had to witness their nightmarish deaths. I might have been able to save myself sooner, and without almost causing my head to explode.

I’d been back here at River’s Edge for a month now. I could have, probably should have, run off to a distant corner of the world, hidden in a cave, and licked my wounds for, like, an eternity. But I was far gone enough to admit that yes, I really did need help. I needed help more than I needed to be proud, or brave, or cool, or even just not gut-wrenchingly humiliated.

So far everyone here had been awesome about what had happened. No one rubbed it in, no one tsked, no one even looked at me funny. Because they’re all so much cooler than I am, right? So much more experienced, both in the ways of the world and the ways of redemption. By not giving me a hard time, they were advancing on their own karmic joyride. So, actually, they should thank me. For giving them so many opportunities to shine.

But it was clear that my centuries-old pattern of not learning anything was not, in fact, working well for me. So I’d sat pinned, a fish on a hook, and had lesson after lesson thrown at me: spellcrafting; the uses of stars in magick; magickal properties of plants, stones, crystals, oils, herbs, earth, sky, water—everything everywhere is connected, and everything around me can be used for good or for evil. My head felt crammed full of facts and lore, history and tradition, forms and patterns and sigils and meanings—if I barfed right now, actual words would spill out onto the floor in a spiky, tangled heap.

“Nas?”

I blinked and tried to look alert, but Anne sat back and put the flash cards down. “Let’s all take a break,” she said. She looked tired—teaching me wasn’t anyone’s idea of a good day at the fair. Doing most things with me wasn’t a rockin’ good time; I know this, and traditionally I haven’t given a flying fig. Lately, with my gradual uphill meandering toward maturity, I’d started to feel guilty and a twinge embarrassed. But so far I’ve been able to shake that off.

“Okay,” I said, trying not to sound elated. I glanced toward the window; the early February sunlight was trying to be brave but not quite succeeding. I judged it to be around ten in the morning and couldn’t help flashing to just a couple weeks ago, when at ten in the morning I would have been tidying the shelves at MacIntyre’s Drugs. If I still worked there. If I hadn’t been fired twice.

“I hope there’s coffee left in the kitchen.” Brynne unfolded her long, lean self and stretched, the tightly wound coils of her caramel-colored hair bouncing slightly. She was the closest thing I had to a friend here, even though we couldn’t be more different: tall and black versus short and snow-white; American versus Icelandic; 230 years old versus 459; cheerful, friendly, confident, and competent versus… not. With a large, loving family versus having no one.

“Maybe I’ll go check the chore chart,” I said. “Do something mindless for a while.”

“Good idea,” said Anne, smiling gently at me. She came over and rubbed my back for a moment—Anne was real touchy-feely, in the literal sense of the words. I’d been practicing my not-flinching, and I barely hunched my shoulders before making myself relax. “Sometimes doing something boring or repetitive is a good way to have knowledge sink in.”

I nodded and picked up my puffy coat. If doing something boring or repetitive was the path to knowledge, then I was on the fast track. Daisuke stayed behind in the classroom as Brynne, Reyn, and I filed out. Of all the students, Daisuke was the furthest along, in my opinion. He was the closest to peace, the one who had the fewest large, visible flaws. But no one ended up at River’s Edge just for kicks. I didn’t know what kinds of things Daisuke had done to make spending years in rehab seem like a good plan, but there had to be something. I’d learned that much in my four months here.

Brynne slanted me a tiny smirk, then strode quickly out the door ahead of me and Reyn, oh-so-obviously giving us space.

I glanced at him, but his face was—and I know you’ll be surprised by this—impassive. As usual, being close to him made my heart carom from skipping a beat to racing, feeling like hard rain hitting a metal roof. I was about to say something that had a 99 percent certainty of being inane when I heard a skittering sound in the wet leaves behind us. We turned to see a small white object catapulting our way: Dúfa, Reyn’s runt puppy. She must have been watching, waiting for him.

Reyn stopped and knelt, the easy smile that crossed his face making my chest feel tight. Dúfa galloped clumsily toward us with a puppy’s single-minded intent, giving a couple of high-pitched yips in case we hadn’t noticed her. She flung herself at Reyn, rising up on her hind paws to lick his face, and I have to say, I knew where she was coming from.

“Okay,” he said softly and held up his hand. “Sitta.” Instantly Dúfa’s small hindquarters dropped to the cold ground, her odd hazel eyes focused on Reyn’s face. He kept his hand up as he stood, six feet of overwhelming attractiveness and danger, and Dúfa’s eyes didn’t leave his face, though she allowed her overlong, skinny white tail to give a small swish. “Okay,” he said, and released her. She sprang up, leaping into the air and yipping.

“She knows sit already,” I said, with my gift for stating the obvious. “In Swedish.” How could I put my next plan into action? I want to lure you someplace. Jump on you. Not think about whether our “relationship” makes “sense.”

“She’s smart,” he said, scooping the puppy up and tucking her into his corduroy barn coat. Her white face and long, floppy ears poked out below his chin, and she looked both adoring and self-important.

A small ding sounded inside my head. “Like, she’s smart, but I’m not?” As soon as the words left my mouth, they sounded ludicrous—I mean, how paranoid am I, to assume a simple statement about his dog was somehow aimed as a dig against me?

“Exactly,” he said coldly, and my eyebrows shot up.

“What?”

He stopped abruptly on the path and turned to me, his face angry. “You almost died in Boston!” he snapped. “You’re a thousand times more powerful than that pathetic waste, but he had the upper hand. You were this close to getting your power ripped from you like ore from a rock!” He held out two long fingers very close together in case I needed visual representation.

“I know!” I said defensively. “I was there! I remember. Muy bad. So?” I crossed my arms and tried not to notice when Dúfa gave Reyn a lick on his neck.

“So why aren’t you studying your ass off?” he exclaimed. “Why are you not taking this seriously? You saw two of your friends die horrible deaths. You should be scared, doing everything you can, reading, studying, practicing.” Narrowing his eyes, he jabbed me in the chest with a strong forefinger, which actually hurt. “Next time you might not be able to pull your magick off,” he said. “Next time you might get killed. You might be dead forever because you were too much of a lame-ass to get your shit together and learn how to protect yourself!”

How dare he? My own eyes narrowed and I started to jab him in the chest, except Dúfa was in the way and I couldn’t tell where she began and ended. So I scowled and gave him the old threatening schoolmarm finger-shaking—so much less satisfying. Between that and the fact that he was almost ten inches taller than me, I might not have presented as fierce a picture as I hoped.

“You—” I started furiously, but I really had no follow-up to that. “I—” As I began to vigorously defend myself, it dawned on me with crushing humili. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...