- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

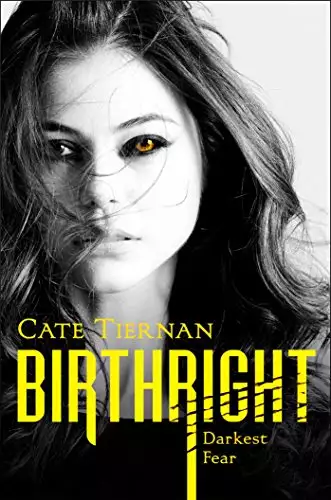

Synopsis

Vivi’s animal instincts are her legacy—and may be her downfall—in this start to a romantic fantasy series that will appeal to fans of The Nine Lives of Chloe King.

Vivi has known the truth about her family—and herself—since she was thirteen. But that doesn’t mean she’s accepted it. Being Haguari isn’t something she feels she’ll ever accept. How can she feel like anything but a freak knowing that it’s in her genes to turn into a jaguar?

Now eighteen, Vivi’s ready to break away from the traditions of her heritage. But all of that changes with her parents’ shocking, devastating deaths and the mysteries left behind. Vivi discovers family she never even knew she had, and a life open with possibility. New friends, new loyalties, and even romance all lay ahead—but so do dangers unlike anything Vivi ever could have imagined.

Release date: January 7, 2014

Publisher: Margaret K. McElderry Books

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Darkest Fear

Cate Tiernan

CHAPTER ONE

“HD,” I SAID, GREETING MY best friend, Jennifer. I slid into the desk-chair combo in front of her, feeling the backs of my legs stick to the plastic seat. May in Florida.

“HD,” she said back, and we gave the lackluster grins appropriate for fifth-period AP US History. Fifth period = the dead zone. It was right after lunch, incredibly hot, and too bright outside, and despite the air-conditioned classroom almost every student in here was about to nod off. I felt like I was moving through muggy air so thick that I had to go slowly and with purpose or I would subside into place, coming to a slow halt, maybe by my locker or something. I bet Ms. Harlow was hating it.

“You did the homework?” I asked, unwilling to lean against my seat because my damp shirt would stick to it. Florida. The state that antiperspirants—and deodorants, if we’re being honest—were created for.

Jennifer nodded and offered me a piece of gum. I took it, crunching through the outer shell to taste the burst of icy mint on my tongue, so bright and sharp it was almost painful. Maybe chewing would help me stay awake.

So—HD is not short for Jennifer, obviously, or for my name, Vivi. It is short for Heartbreaking Disappointment, and we’d been calling each other that since eighth grade, which was when it became so horribly clear that was what we were to our parents.

• • •

“Everyone take out your notebooks,” Ms. Harlow said. “I know you’re all excited about finals next week, so let’s start reviewing topics that will be on your exam.”

Last high school finals, I told myself. Next week is the last time you’ll ever have to take a high school test, ever. Soon you’ll be free, free, free . . .

“Ready for tonight?” Jennifer whispered as we opened notebooks and fished in our backpacks for pens. In the seat in front of me, Annamaria Hernandez flipped her long cheerleader hair, and it almost hit my forehead. Even today, even during fifth period, Annamaria looked pert. Her skin was smooth and dry, her hair was unfazed by the 100 percent humidity—even her clothes seemed crisp and clean. My Piggly Wiggly T-shirt had, let’s face it, never, ever been crisp, even before it had been washed so many times it was starting to shred. My skin was shiny and damp, and I didn’t know what my hair was like because I’d gathered it into a big lump on the back of my head and stuck a pencil through it to keep it there.

Answering Jennifer, I nodded briefly. She had already wished me happy birthday first thing this morning, and she and some of my other friends had decorated my locker. I wished they hadn’t duct-taped condoms to the locker door, but those had all been stolen by second period, so it was okay.

“What’s on the menu?” she asked, pitching her voice below teacher-hearing range. Ms. Harlow was on the other side of the classroom, answering Bud Baldwin’s question about how long the exam would be. (His name really was Bud. He was Buddy all through lower and middle school, but had finally drawn the line in high school.)

I glanced over—now he was asking exactly what material would be covered. Probably everything we’ve been taught in this class, Buddy; that’s why they call it a final.

Keeping my voice low, I said, “Shrimp empanadas, egg rolls, fish tacos, coleslaw, and corn bread.” Every year my parents took me on a picnic for my birthday. It was kind of corny, but it was a tradition, and they were very big on tradition. To use almost criminal understatement. Lately we’d been fighting almost constantly, and I wouldn’t have been surprised if they’d ditched any birthday festivities at all. But my mom had asked what I wanted like nothing was wrong, and I’d told her. Like nothing was wrong.

“Yeah, that won’t make you sick,” Jennifer murmured, and I smiled.

“Girls?” said Ms. Harlow. “Pay attention here.”

I sat up straighter and tried for at least the illusion of alertness. Next week was the last week. Just one more week.

• • •

Some kids were embarrassed to be seen in public with their parents and tried to walk ten feet behind them, or ignored them when they talked. I didn’t do that. In public my parents were fine—not really old like Chris Gater’s folks, who’d both been almost fifty when he was born. Or oddly young like Tara Hanson’s mom, who was now literally thirty-four. Which was just bizarre.

No, on the surface my parents were super nice, friendly, attractive, had okay jobs. Yes, they were Brazilian, which could have been weird except this was Florida and there were tons of various ethnicities here. Their accents didn’t stick out like they might somewhere else. In public, on paper, Mami and Papi were great. It was all the hidden, underneath stuff that made my head explode.

After school Jennifer gave me a ride home, as usual, in the Volkswagen bug she’d inherited when her older sister had gone to college. She pulled into my driveway, and for a minute I just sat there, trying to feel eighteen.

“Hey, you can get married now, right?” Jennifer asked brightly.

No. Not ever. Never. “Yep. Course, I need a fiancé first. Or a boyfriend. Or more than three dates in the last two years.”

“That’s your own fault,” Jennifer said. “Guys ask you out but you never go.”

And I could never tell her why. I sighed and rolled down the window—the car was instantly stifling without the AC on. It wasn’t like we had to slog through three or four months of summer but then in September we would have a real autumn. There was no autumn in Florida. There were nine months of summer and three months of yucky chill.

“You can sign up for the armed forces,” Jennifer went on. “And vote.”

“Yep.” I looked out the window at my house.

“You don’t want to go in. It’s been bad?”

I let out a breath. “Yeah. I mean, it’s not like they’re evil. Just determined. Last night they actually said they’d move back to Brazil in order to fully immerse me . . . in their culture. I was like, I’m going to college in three months.”

“Crap,” Jennifer said, frowning. “I’ve never understood exactly what the issue is. Like, how do they want you to conform? Be more Brazilian? Speak Portuguese at home? Or be more girly?”

I rolled my eyes. My clothes choices did make my stylish mother crazy, but it was such a tiny chunk of the glacier that it hardly mattered. It was another thing I couldn’t explain to Jennifer. I couldn’t explain it to anyone. With any luck I would go to my grave without anyone knowing.

Jennifer patted my knee, her short blue nails glittering in the sun. “It’ll be okay, you li’l Heartbreakin’, Disappointin’ thing. You’ll have a nice picnic, and then it’s the weekend. And three months from now you’ll be headed to Seattle.”

I nodded, trying to let that make me happy, like it usually did. “True. Three months. Then it’ll be cool, gray weather all the time. Mountains. Three thousand miles from here.” Of course I would still be me, which was a problem, but there I’d have better luck pretending I wasn’t.

Jennifer made a sad face. “You should come with me to New York.”

“You should come with me to Seattle.” Jennifer and I had been best friends since third grade, and I’d thought we’d stay that way our whole lives. As I got older, though, I realized that I’d be forced to leave Jennifer behind at some point. Because best friends knew each other deep down, shared almost everything with each other. And I was already keeping an enormous secret from her. And always would.

I had to get as far away from here as possible. And she had to go to Columbia in New York City because it was the only school her parents would pay for. The reality of not seeing each other almost every day was starting to sink in, one gray inch at a time. Most of me was already dreading the end of the summer, when we would split up, but a tiny part was relieved, also. Because then I would be free—free to keep my secret. Right now that carried so much weight that it made even losing Jennifer almost seem like a reasonable price.

The front door opened and my mom came out.

Jennifer sighed. “Your mom is so gorgeous. Despite the crazy-making.” She said this every couple of months, in case I had forgotten. And it was true. My mom’s shiny black hair swung in loose waves below her shoulders; her skin was smooth, tan, and clear, with some laugh lines at the corners of her eyes. Her unusual golden eyes were large and almond-shaped, making her look exotic and foreign. Ha ha. Today she was wearing tailored black shorts and a fuchsia sleeveless polo top. Gold bracelets jingled on her toned arms, and black Tory Burch thongs showed off her pedicure.

Smiling, my mom came to the car. “Zhennifer!”

“Hi, Ms. Neves,” Jennifer said. While totally loyal to me, she couldn’t help adoring my mom. “Vivi was telling me about this year’s menu, the Pepto-Bismol special.”

My mom smiled, her teeth white against her tan skin. She was forty-six but looked much younger without working at it. Strangers turned to look at her almost everywhere we went—partly because she was beautiful and partly because she was intensely alive, incredibly charismatic, open, genuine, generous. I’d never seen anyone more feminine, but it was a strong, womanly thing unrelated to pink ruffles or being dainty. Everyone loved her. And I did too, I did. But it was all so much harder than anyone realized.

“I know, can you imagine?” my mom said. “And then coconut cake. Tomorrow you come to bring us chicken soup, okay?”

Jennifer laughed. “I will. You guys’ll need it.” Turning to me, she said, “Did you make the cake or did you let your mom attempt it?”

“I made it,” I said, getting out of the car and taking my backpack from the backseat. I’d made all of our birthday cakes for years, trying more ambitious recipes and decorations each time. My mom was definitely a good cook and could make a perfectly decent cake, but I made great cakes.

“She didn’t trust me to make it,” said my mom, pretending to look exasperated.

“It was complicated,” I said. “Thanks for the ride, H. See you tomorrow.”

Jennifer started the car and nodded. “Pick you up at four. Then movie at seven.” As she pulled out of the driveway, my mom came over and kissed my forehead, then lightly put her fingers where she had kissed, like she always did, as though to make it stick. She had to go up on her toes these days—at five foot ten, I was a good six inches taller than her. I stood there stiffly, though my deepest core longed to melt into her arms, to just be able to love her. But how could I? It would be the last wall breaking down, the last wall that kept me being myself and not just a clone of her and my dad. That would be terrible. Terrifying. Literally my worst fear.

“My darling,” she said, her eyes shining with love but shaded by caution and crushed hope. “My darling. Eighteen.” Her hands were on my shoulders; the sun glittered on the diamonds in her wedding ring.

I nodded. We’d done this already this morning. “Yep,” I said. “You’re home early.” My mom taught French and Spanish at a high school in the next county. Her students loved her.

“I had to get home and make your picnic, right?” she said, putting an arm around me as we walked toward the house. “Papi should be home any minute. Where’s the big beach blanket? I couldn’t find it.”

“I think it’s in the luggage closet,” I said, and entered the cool, dry air of our house.

• • •

An hour later my dad was home, the car was loaded, and I climbed in the backseat of his black Escalade next to the laundry basket filled with food. The whole car smelled so good that my mouth tingled with anticipation. But even this, even making my picnic, felt like a bribe. Like, if we do all these nice things for you, then you should do what we want. It made me beyond furious. Ironically, besides this one huge thing, they were fine—didn’t hassle me about homework or grades, liked all my friends, let me borrow the car, didn’t micromanage my life. We could be happy. I tried to be a good daughter, in every way except the one they wanted. Our house could just be calm and happy. Instead of a minefield.

Sudden anger ignited in me, and I wanted to refuse to go, refuse all the fabulous food my mom had made. Stay home alone with my cake. It would devastate her. Both of them. But then I had already devastated them lots of times.

I was quiet on the way to Everglades National Park. My parents tried to chat, tried to be cheerful, but I could swear that my mom seemed disappointed every time she looked at me—my thick dark hair pulled back into a plain ponytail, my ratty Piggly Wiggly T-shirt, my faded cutoff sweatpants that were the most comfortable shorts I owned.

When I was in ninth grade, she had quit telling me how pretty I could be if only I made an effort. Now it was more like subtext every morning when she saw how I had dressed for school that day.

Sometimes I saw cute clothes at the mall or somewhere and was almost drawn to them, but I always stopped myself. I wasn’t trying to make myself as unattractive as possible—that was sort of a by-product. But not caring about how I looked was another way to not be her.

The Everglades are in a park, but they’re more like a state all by themselves. We’d been coming here to picnic all year round for as long as I could remember. Years ago we came with family friends, but now it was almost always just the three of us. For a while I had lobbied for someplace air-conditioned, but though I could choose the menu, I could not, apparently, choose the venue.

“Has Jennifer found a dress for the prom?” my mom asked, searching for a relatively safe topic.

I shook my head. “We’re going to the mall tomorrow to look again, and then to a movie.”

“I saw my friend Marielena the other day,” Mami said casually. “She said Aldo was doing well . . .”

The hints about finding a nice boy—almost always some son of one of their friends—were so mild compared to the other stuff that it was easy to let them slide. I kept my voice deliberately casual as well. “Oh, good.” I looked out the window as we drove through the familiar park gates. My stomach was starting to knot up. I just wanted to get through this. Later I could go home and lock myself in my room as usual.

Mami was silent, and I saw her and Papi exchange a quick glance.

“Gosh, I’m hungry,” I said, sounding artificial even to myself. “It all smells good.”

Mami forced a smile. “I hope so. I just can’t believe my baby is eighteen. You were the most perfect baby . . .”

Only to become a Heartbreaking Disappointment when I turned thirteen.

“Okay,” Papi said, parking the Escalade. “I guess you women want me to carry the basket, eh?”

“Yes,” my mother said, and they smiled at each other, genuine smiles. Jennifer thought their relationship was so romantic—they were still really nice to each other and truly liked to be together. Her parents hardly talked—her dad practically lived in the little workshop behind their garage, and didn’t even come in for meals for days sometimes. The main things her parents still agreed on were that Jennifer had to follow her older sister, Helen, to Columbia; both girls had to spend part of every summer with their family in Israel; and they had already started saving money for their daughters’ weddings, so Helen and Jennifer had better come through and the guys must be Jewish.

Helen might be able to accommodate that, but Jennifer was gay, as she’d announced at her bat mitzvah. Mrs. Hirsch had actually fainted, right in front of everyone. I’d never seen anyone faint before.

So on Jennifer’s thirteenth birthday, she’d had her bat mitzvah and made her mother faint in public. On my thirteenth birthday, I’d found out that I was a freak, a monster, an abomination. Of course, I hadn’t told Jennifer the truth—I’d mumbled something about how my parents wanted me to be less American and more Brazilian, and that they wanted me to promise to follow their weird Brazilian religion. In that context, I was using “Brazilian” as a euphemism, but Jennifer didn’t know that. Anyway, it had been a rough year for everyone. And Jennifer and I had started calling each other HD.

“Viv, grab the blanket, querida,” said my dad, pulling the basket out. “Aracita, can you bring the cooler?”

“Of course,” my mother said, taking the small cooler from the back of the car.

My dad, Victor, was fifty-one but looked at least ten years younger, as if he were a well-preserved movie star instead of a regional manager for a huge office-supply chain. Without being prejudiced, I could say that he was the handsomest dad out of all my friends’ dads. He had thick black hair, just starting to be tinged with a few silver threads, green eyes with long lashes, and a strong, straight nose. When I was little I’d thought he was the most handsome man ever. I mean, objectively, he still was, but now I knew that nothing was that simple.

Mami led the way, I followed, and Papi lugged the basket behind me. We trudged along the hiking path for a good fifteen minutes, trying to avoid the occasional buzzing clouds of gnats and no-seeums. It was almost six in the evening but still eighty-eight degrees and sweltering, becoming only more sweltering as we got farther into the pine trees. My skin was sticky and damp, sweat ran down my temples, and all I wanted to do was take a cool shower. I mean, what was wrong with a nice dinner at Ruby Tuesday? It was air-conditioned. Was it that they wouldn’t be able to harangue me if we were surrounded by other people? Even better.

Five minutes more on this trail and we would run into a cypress swamp; if we turned east for a mile, we would come to one of the mangrove stands.

We ignored the clearing with the picnic benches and went instead to a small glade, only about fifteen feet across. It was our special and secret picnic spot, remarkable because it was flat and root-free, shaded by pines and a few knobby cypresses. All around it trees grew so thickly that the light was dim even at midday. I spread the blanket and hoped to get through most of dinner before everything started.

Fiendishly, they waited till I had my fork poised over a slab of my rich, moist coconut cake, its scent swirling up to my face. I’d been thinking about it all day, fantasizing about just planting my face in it and scarfing it up. Now I was much too full, of course, but by the gods I was going to get this down somehow.

“Dearest,” said Mami, looking strained, “eighteen years ago today, you came into our lives.”

I tried to smile through a mouthful of cake.

The most perfect baby.

“The most perfect baby,” my mom said.

Every time she said this, I wondered if she was comparing the perfect baby me to the current me, which seemed by any standard to be considerably less perfect.

Mami hesitated, then went on. “When you were thirteen, we shared with you the wonder, the beautiful mystery of our kind.”

My throat closed up, the coconut cake turning to a lump of florist’s foam in my mouth.

Papi looked serious. He put down his fork and rubbed the back of my neck, which he always did when he wanted to talk seriously to me. “Querida, now you are eighteen. You know we’ve tried so hard to show you the joy in being who you are. What you are.”

The cake moved very slowly down my esophagus, as if I’d swallowed a whole hard-boiled egg. I breathed through my nose, hoping I wouldn’t gag.

“I don’t want any part of this,” I mumbled, my mouth bone-dry. How many times had I said that? Like a million? “This isn’t me.”

Sounding near tears, my mom said, “Of course it’s you, Viviana. Of course—”

Papi went on quickly, “But now you are eighteen, and when a haguari child turns eighteen, she or he is given the family book.”

My brain rang with the most awful word I knew: “haguari.” My parents pronounced it “ha-HWA-ree,” but I’d heard friends of theirs say the g: “ha-GWA-ree.” It meant “jaguar people.” A bit hysterically, I wished that it meant people who totally, totally loved their British sports cars.

“The family book?” I asked faintly. It was the first I’d heard of it. Could they read the dismay on my face? Of course they could.

As we’d sat there, the sun had gradually sunk below the line of trees, and our little glade was now even more private, deeply in shadow. I wanted to jump up and run into the pine-scented darkness and just keep running. I wanted to leave them forever, and knowing this made me want to die. Do you know how hard it is to feel that the people you love the most can’t help destroying you?

“Yes,” said Mami. “It has the history of our people and the history of our family. When you marry, you will continue the book for your children.” She spoke firmly, as if there were no question I would marry and have children—children like me. Like them. Oh, gods. If only I could hold on until I could go to Seattle. It couldn’t come soon enough.

I shook my head. “I’ve told you every way I know how,” I said tightly. “I understand what you are, but I don’t want to be like that. I want to be regular. You can yell at me every day for the rest of my life, but it won’t change my mind. I want to be like me.” My face was hard. “I don’t want to be like you—I mean . . . the other part. The . . . people part of you is fine. But I’m rejecting the other part.”

“How can you say that?” my mother cried, as if this were a brand-new argument, as if I hadn’t already said those exact same words a hundred times. “You haven’t even tried—” She stopped abruptly as my dad put a hand on her knee.

“Whatever you decide, our book is in—” Papi began firmly, but his words were drowned out by a sudden, startlingly loud growl that made us all jump. An animal growl, coming from . . . behind the trees? In the darkness there? Instantly my parents were on their feet, and my mother grabbed my arm and hauled me to mine.

“What’s that?” I asked, peering tensely through trees. A wild dog? Something big. Maybe even a Florida panther? They weren’t supposed to be in this area. My blood had turned icy with the sound, and the little hairs on my arms were standing up. There was another growl from the woods, sounding like the snarl of a circus cat when the trainer pokes it with a stick.

And then . . .

“Oh, my gods,” I muttered, appalled, wanting to look away. My father had started to change, right there in front of me. It was amazingly fast, like a sped-up film. I’d seen it happen only once before, on my thirteenth birthday, and it had been horrifying. Since then I’d seen him in his other form just a couple of times, and never on purpose.

His other form. His jaguar form.

He was already on all fours, his clothes slipping off, one shirtsleeve ripping. His face had broadened, his jaw jutting forward, and thick dark fur was covering his tan skin. Bones shifted and moved; muscles swelled; limbs elongated; his spine bent and lengthened. It was repulsive, disgusting. Grotesque.

From deep in his throat an answering snarl—raw, angry, full of menace—made me suck in my breath. His teeth were long and knifelike and—

“Vivi!” My mother’s voice was harsh, her grip on my arm painful. “Go! Run!” She pushed me away, toward the edge of the clearing.

I stared at her. “What?”

“Run! Get out of here!” Now her face too was broadening, starting to transform, her shoulders hunching, her spine curving down sharply. I didn’t want to see this. What was happening?

“Run!” she said again, but it came out as a half roar. I burst into tears, turned, and ran.

• • •

I’d been coming to this park my whole life, had spent countless sweaty hours on the hiking trails, canoeing through the swamps, watching baby alligators from viewing decks above the waterlogged, sun-soaked fields of sedge grass.

Now I ran blindly, my panicked brain barely registering that I had left the trail and was crashing through the woods. Broken twigs jabbed my feet, scratched my arms and face, and still I plunged forward. What was happening, what was going on, should I call for help—?

Another furious, high-pitched roar wove its way through the trees to my ears, making my heart pump harder and my stomach twist in fear. Was it coming after me? I refused to look behind me. Didn’t want to know.

And then, with no warning, it began to happen, the way I’d always feared it would: The world shifted in my eyes, details becoming more precise, some colors fading, some enhanced. My running feet sounded like bricks crushing the leaves on the forest floor, the snap of twigs like rifle shots echoing in my ears.

My running became awkward, unbalanced as my legs got tangled in my shorts. I fell, my hands outstretched, and then I was racked with sudden pain that made me crumple up and cry out. My joints were bending unnaturally, dislocating, the bones lengthening horribly. My face was splitting, my jaw unhinging; my skull was in a vise. Every muscle screamed, its fibers being split and stretched. My clothes, annoyingly in the way, fell off or ripped.

Curl up pant pant pain

Curl up small

Muscles hurt close eyes smell dirt smell pine smell me animal me my fur

Pain breathe in slow shallow

Smell dirt smell fear

Open my eyes the pain is fading

Sun down dark but shapes outlines see quite well see everything

Trees and leaves I see lines depth land picked out so sharp

Strong scents fill my nose my mouth pine cypress stagnant water thick and green

Rabbit and insects pungent like roly-poly bugs I smell saw grass and pine needles and birds

Can’t hear my parents where am I how far away am I

Where are my parents I get to my feet I am on all fours

I am solid I have strong muscles I am powerful I am jaguar me I am a jaguar

Before it hurt so much took so long was a birth

This is still awful

These eyes can’t cry tears

There is no movement it has stopped

Every creature senses me and has gone silent becoming still like a tree a rock a root

Because I am a predator I am at the top of the food chain

Where did I come from which way did I come my new eyes see everything my new eyes see weird but so well

Should I go back to find my parents

The snarls were so scary from the purple shadows maybe I should wait here

Mami said run get out of here now

I sit down it is odd my haunches sit but my shoulders stay up I have haunches it is funny

Mami Papi where are you will you come get me

Ground is not safe want to be up

Cypress tree here I coil muscles and jump like a spring like a jumping bean

I float I land on a branch my claws are steel hooks on the branch t

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...