- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

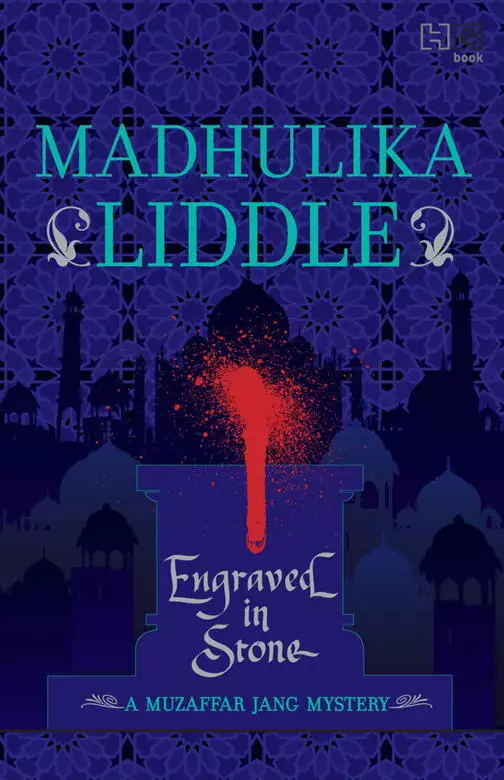

Synopsis

Two years after the Taj Mahal is finally built, many secrets shroud its walls...

In Agra to escort home the beautiful Shireen, Muzaffar Jang – maverick nobleman and ace detective – reluctantly finds himself at the centre of yet another murder investigation when Mumtaz Hassan, a prominent trader, is found dead under mysterious circumstances. The Diwan-i-kul, Mir Jumla, on his way to invade Bijapur, hands the task of finding the killer to Muzaffar. With almost no evidence to work with except an ambiguous scrawl on a scrap of paper found clutched in the dead man’s fist, Muzaffar knows he must find the killer before the Diwan-i-kul returns if he wants to save himself an invitation to a beheading.

As he begins to uncover the dross beneath the golden opulence of the dead man and his murkily amorous past, Muzaffar chances upon another mystery: a long forgotten tale of a woman who vanished inexplicably one evening.

Muzaffar Jang once again pits his wits against an array of potential suspects – even as he loses his heart...

'

Release date: November 15, 2012

Publisher: Hachette India

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Engraved in Stone

Madhulika Liddle

The double entendre was doubtless deliberate, the speech often rehearsed and just as often used. Muzaffar Jang, whose attention had been wandering, glanced sharply at the speaker. A good head shorter than Muzaffar’s own imposing height, the man made up for it with a magnificent turban, a pristine white silk of no less than ten yards. It blossomed out like the canopy of a stunted and spindly tree above the narrow shoulders and almost skeletal figure of the man. Below that remarkable turban was a face of unusual beauty. Yes, beauty, thought Muzaffar; not a rugged handsomeness, as one might expect in a man. It was a slim face, with a well-trimmed grey beard and moustache. The lips were thin, the eyes hooded but occasionally sparkling with sudden brightness. A serene, tranquil face. The face of a saint and the words of a pimp.

‘You will not see another like her, huzoor,’ the horse trader purred. ‘Why, the atbegi himself – the Master of the Imperial Horses – has bought palfreys from me, and Turcoman horses like this one. If huzoor seeks a horse, there is none more reliable than Shakeel Alam. You may ask anyone.’

Muzaffar looked away, letting his gaze wander across the vast covered stretch of the Imarat-e-Nakhkhas, the building in which Agra’s nakhkhas, the cattle market, was held every morning. He had expected crowds and chaos; the sights and smells of horses, oxen, and camels; the bustle and din of men and animals mingling; but he had not expected it on this scale. The nakhkhas was huge, stretching along the bank of the Yamuna north of the fort. The courtyard, its flagstones already littered with straw, grain and steaming dung – where stable boys had not yet been quick enough to clean up – was a large rectangle, its peripheral walls holding in a constantly shifting mob that haggled and wheedled, laughed and fumed, and occasionally resorted to fisticuffs.

The wall facing the fort was pierced by a massive gate. It was red sandstone like the encircling walls, and devoid of any decoration but for an inconspicuous repetitive pattern of carved lotus buds. Nearest the gate were the sellers of equipment and accessories: the men who had been granted stalls, little rooms built along the inside of the wall. A couple of steps up, and buyers could examine for themselves the feed bags, the saddles, bridles, and the mane coverings known as yalpusts. Some stalls were occupied by the wealthy merchants who dealt in the more luxurious goods, the items reserved for the stables of the Emperor or those of his highest ranking noblemen.

One merchant, a rotund but energetic man in his late forties, was prattling on while his servant exhibited their wares to a trio of noblemen. A caparison embroidered in gold; another of fine brown leather – soft as cotton, said the merchant’s plump fingers as they flitted, curling and uncurling in rapid succession. There were saddlecloths of chintz, quilted and finely embroidered; flocked yalpusts to decorate horses for festivals – or for the supreme honour of carrying an amir to his wedding – and metal rings in the shape of bells, to be attached to fetlocks.

‘Huzoor appears to be more interested in the equipment than in the horses,’ said the horse trader peevishly.

Muzaffar looked at the mare Shakeel Alam was exhibiting with such pride. She was a beauty, muscular yet slender and utterly feminine from the tips of her fine ears down to her tiny hooves. A superb palomino, her golden coat glistening with a coppery sheen that contrasted with the creamy silken mane and tail. Muzaffar reached out a hand and stroked gently down between the large eyes to the tapering muzzle.

‘Can you imagine her in the field, huzoor? Swift, turning with the speed of lightning. An archer could shoot from that back, now here, now there – without missing a shot. And she would be equally fine as the mount of a noble gentleman such as huzoor. I can well imagine her being the mount of a bridegroom, her legs red with henna and her equipment embroidered with gold. Ah, that would be a sight to please any eye.’ The man paused, watching Muzaffar for signs of weakening.

The young amir ran his fingertips down the horse’s sloping shoulders and along her gleaming flanks before asking, ‘How much?’

The merchant smacked his lips. ‘Ah, the love and care I have lavished on this one, huzoor. She has been fed from the day of her birth on nothing but barley, mutton fat, raisins and dates. With my own hands have I covered her with thick felt to sweat out every last pinch of fat –’

‘Muzaffar!’ The name rang out across the interior of the Imarat-e-Nakhkhas, distorted by the many competing sounds: the lowing of cattle, the neighing, the occasional whicker and grunt, the dozens of simultaneous conversations in progress. Muzaffar frowned, puzzled, then turned back to the horse trader. It may well have been another word, not even his name. And even if it had been what he had thought he heard, Muzaffar was not an uncommon name. There were probably a dozen Muzaffars in the marketplace at the very moment. One of the servants patiently displaying caparison after caparison for an indecisive buyer, perhaps. Maybe even one of the stable boys mucking out the Arabian grey’s stall in the next bay. It was a sobering thought.

The horse trader was blabbering on, but Muzaffar whirled around, a smile lighting up his face as the voice – now recognizable and just a few feet away – bellowed his name again. A gorgeously attired figure pushed through the rabble of the nakhkhas, weaving an intricate path between the dung and the straw. The fine woollen choga of the newcomer was a bluish grey, embroidered along the hems in crimson and silver. The boots shone, the turban was a dream in scarlet; and three necklaces of perfectly matched pearls hung down the front of the choga. Even the large muslin handkerchief being hurriedly pulled out of the choga pocket was prettily embroidered.

Akram, thought Muzaffar with a sudden surge of affection, was well capable of asking Iz’rail, the angel of death, to wait while he tried out yet another jewel or straightened his turban.

The man came to a halt amidst an awed silence. He glared briefly at the stable boy who had stopped in the middle of currying the grey Arabian and was staring fixedly. Then, with the handkerchief whipped up suddenly to his nose, the man let out an explosive sneeze. When he had wiped his nose and pitched his handkerchief into the heap of rubbish in the corner of the stall, he looked at Muzaffar with watery red eyes. ‘I’ve been yelling for you for the past five minutes,’ he said hoarsely. ‘What in the name of Allah are you doing in Agra?’

It took Muzaffar less than a minute to have the horse trader’s assurance that he would be there the next day – and the day after. Muzaffar said that he would be back in a day or two, then moved off, threading his way through the crowds with his friend Akram at his heels.

Beyond the horses were the camels, long-lashed, supercilious animals from the Thatta region of Sind and darker double-humped ones from up north. One of the traders had fitted out his best specimen in a style befitting its value. The camel had been rubbed down with pumice and sesame oil, then given a final scrub with buttermilk; the faint, slightly tart aroma of the buttermilk still hung in the air. The camel’s saddle was of intricately embroidered leather, its edges fringed with heavy tassels. A young amir, goaded on by the shouts of his friends around, was climbing into the camel’s saddle as Muzaffar and Akram squeezed their way past.

‘I hate camels,’ Akram muttered as the camel lurched to its feet, the bells festooned from its girths and breast bands tinkling merrily. ‘They jerk about so dreadfully. I always think I’m going to be sick.’

They passed the cattle pens, each with its own lowing, shifting herd. One trader even had a small herd of prized silver-grey buffaloes, but the farmers milling around merely glanced covetously at the buffaloes and then moved on to the more affordable milch cows, examining the udders, peering into the cows’ eyes, and standing back to look at the animal from a distance. A high-yielding cow, it was widely believed, would be one with a body shaped like a wedge.

Muzaffar and Akram stepped out through the gate and onto the riverbank. Three hours past sunrise, the mist had still not lifted completely. It curled moist tendrils through the trees, obscuring the boundary between river and land, throwing a shifting blanket of white across the blurred outlines of the havelis dotting the shore.

‘Uff,’ Akram said, with a sudden shiver. ‘I’d forgotten it was so cold outside.’ He pulled his choga closer about him and huddled deeper into it. ‘Where’s your horse, Muzaffar?’ His breath floated on the chill morning air in a wisp of white.

From beside the gate, a beggar scuttled forward, one arm withered and the other clutching a chipped earthen bowl. Muzaffar reached into his choga and handed the beggar a daam as he replied to Akram’s question. ‘At a haveli down the river, recovering from a bout of thrush. That’s why I came to the nakhkhas; I need another mount. I had to hire a boat to bring me here.’

The beggar, mumbling blessings on Muzaffar, retreated to his post near the gate, just close enough to the path to draw the attention of passers-by, just far enough to not get trampled underfoot.

‘Thrush?’

‘Yes, a bad case. Hooves gone very black in places, and smelling like death. I couldn’t possibly ride him.’

Akram tut-tutted. ‘Not lame, is he?’

‘No.’ Muzaffar looked at his friend sympathetically as Akram sneezed again. Akram fumbled around in his choga pocket for a fresh handkerchief and muttered, ‘I should be like the Europeans, eh, Muzaffar? Blow one’s nose in a handkerchief, then shove it back into a pocket as a keepsake. I thought I had some spare bits of muslin in here… ah, yes.’ He wiped his nose and threw away the handkerchief.

‘Standing out here in the cold and damp isn’t going to do anything for this cold of yours,’ Muzaffar said. ‘I’d liked to have gone to a qahwa khana for a cup of coffee, but not having a horse is a problem –’

‘I have a spare. I’d brought a groom along to the nakhkhas, just in case I decided to buy a horse. He has a horse you can borrow. It doesn’t look much, but it’s sturdy enough, I daresay.’ Akram paused. ‘But on one condition. We will not go to a qahwa khana. We will not venture anywhere near a qahwa khana. I will not be bullied into having any more of that horrid beverage.’

‘I’d gone to Ajmer,’ Muzaffar said, swirling the steaming coffee around the earthenware cup. Chowk Akbarabad, Agra’s main market, had its share of eateries and kabab-sellers, but the stench of reused oil wafting from the first such establishment they had entered had sent Akram scurrying out, looking faintly bilious. After that, it had required little persuasion on Muzaffar’s part to steer his friend to a qahwa khana.

Despite the low hum of conversation from the groups of patrons scattered across the hall, Muzaffar guessed the coffee house was not thriving. The plaster was peeling in places; one corner had a large patch of damp, and the mattresses were thin and cold underneath the greying sheets. Muzaffar dug absently with the tip of his dagger at a grimy encrustation of long-ago food along the inside edge of the salver on which the tall, narrow-necked coffee pot stood.

‘My sister, Zeenat Begum, wanted me to accompany her to Ajmer so she could offer prayers at the dargah,’ he said. ‘On the way, she made friends with a young woman from Agra, who was also headed for Ajmer. By then, Zeenat Aapa was longing for some female company. Before I knew it, she’d befriended Shireen and her entourage and made them part of our entourage.’

He grimaced as he examined the greasy black tip of the damascened blade. ‘Anyway, when our pilgrimage to Ajmer was over, Zeenat Aapa insisted that we accompany them back to Agra. She wouldn’t hear of Shireen travelling without a female chaperone.’

Akram raised a curious eyebrow. ‘Shireen, is it?’ he grinned, somewhat lopsidedly. ‘I see.’

‘I’m sure you do,’ Muzaffar’s voice dripped acid. ‘You see things where there is nothing to be seen. But what are you doing in Agra? I thought you had no plans of moving out of Dilli for a while at least.’

The tepid sunlight streaming in through the doorway of the qahwa khana was blocked out momentarily as a small group of men, European mercenaries by the looks of them – and one man in a long robe, his hair cut strangely in a fringe around a perfectly round, bald patch at the crown – stepped in. Akram watched them move to one of the tables at the far end of the room, next to one of the windows that looked out on the bustle of Chowk Akbarabad.

He sighed. ‘I’m here giving Abba company.’

Muzaffar waited.

‘He was ordered by the Diwan-i-kul to accompany him to Agra.’

‘Ah. With a substantial army, I suppose? I noticed much activity off towards Sikandra when I was riding into Agra yesterday. Elephants, horses, much dust and noise. I didn’t stop to find out what it was all about.’ Muzaffar sipped his coffee. ‘The Diwan-i-kul, eh? His arrival in Agra has nothing to do with the mess down in Bijapur, has it?’

Akram nodded sombrely. ‘It does. He’s headed for Aurangabad, to join up with the armies of the Shahzada Aurangzeb.’

Muzaffar frowned, suddenly filled with a sense of foreboding. It had been less than six months since the arrival in the court at Dilli of the cunning Mir Jumla, the former wazir of the peninsular kingdom of Golconda, fabled land of diamonds and wealth untold. The tales whispered about Mir Jumla were legion: that he had cast a spell on the Shahzada Aurangzeb, who danced like a willing puppet to Mir Jumla’s every command; that he had presented cartloads of diamonds, rubies and pearls to each of the Baadshah’s most influential noblemen and Allah alone knew how much to the Emperor himself; and that he had actually succeeded in seducing the mother of the king of Golconda.

All bazaar gossip, of course, but there was perhaps a grain of truth hidden deep in it. Zeenat Begum’s husband and Muzaffar’s brother-in-law, Farid Khan, the kotwal of Dilli and a man not inclined to exaggerate or gossip – had shared with Muzaffar some of what he had learned through his connections at court.

Mir Jumla was originally from the city of Isfahan in Persia. Born Mohammad Sayyid, he was from a Sayyid family, respected only for its supposed descent from the Prophet; the head of the house, Mir Jumla’s father, had been an oil merchant of little consequence. Mir Jumla, however, was a different kettle of fish, ruthlessly ambitious and ready to use intrigue and bribery to earn him both wealth and power.

Mir Jumla’s ambitions had resulted in his gaining employment as the clerk of a diamond merchant, and eventually arriving in India at the entrepôt of the diamond trade: Golconda. Gifts left, right and centre, accompanied by much flattery – and perhaps even some of that seduction which people hinted at – had made Mir Jumla the wazir, the chief minister of Abdullah Qutb Shah, the king of Golconda. Mir Jumla hadn’t stopped at that; his ambitions were higher and his nest far from adequately feathered. He spent his time at Golconda farming out diamond mines, gathering in gems by the sackful – and finally attracting the attention of his boss Abdullah Qutb Shah, who had realized all too late that he was being hoodwinked. Secret plans were hatched to get rid of the corrupt wazir; but Mir Jumla, a step ahead of his sovereign, had wriggled free and opened negotiations both with the Sultan of the neighbouring state of Bijapur, and with the prince Aurangzeb, Mughal governor of the Deccan.

In Shahzada Aurangzeb, Mir Jumla appeared to have found the ultimate champion, though Farid Khan, in his recounting of Mir Jumla’s past to Muzaffar, had a cynical comment to make: ‘No doubt the shahzada has his own axe to grind. The Baadshah lacks the will or the power to hang on to the throne much longer. And Dara Shukoh, no matter if he is the proclaimed heir, does not have the military experience to be able to withstand an attack if Aurangzeb decides he wants the throne for himself – which I am convinced he does. The more powerful friends Aurangzeb makes, the more he strengthens his own hand.’

And so, supported by a commendatory letter from Aurangzeb, Mir Jumla had been appointed a Mughal mansabdar or ‘holder of rank’ – and awarded an army of five thousand horsemen of his own. With Aurangzeb, he had gone off to plunder Golconda, and had withdrawn only after the Emperor Shahjahan, bribed by the Qutb Shah, had ordered the two Mughal commanders to accept the indemnity offered by Golconda.

Six months later, in July of what was, to the Europeans, 1656 AD, Mir Jumla had presented himself in the court at Dilli. It had been a typical Dilli summer: blisteringly hot, the sun blazing down mercilessly, reducing the Yamuna to a trickle and leaving man and beast yearning for the monsoon. But Mir Jumla, bowing and scraping and mouthing insincere words of endless fidelity to the Baadshah, had brought relief at least to the Emperor, if to no one else. He had presented his liege lord with a diamond of almost unbelievable beauty and size, along with a mouth-watering array of lesser diamonds, rubies and topazes. The Baadshah had summarily bestowed the title of Muazzam Khan on Mir Jumla and had appointed him the Prime Minister, the Diwan-i-kul. And Mir Jumla had reciprocated by suggesting to the Emperor that instead of distant Kandahar – which the Baadshah had been considering invading – Bijapur, closer home and by far the wealthier, would be a more lucrative target for a military expedition.

The king of Bijapur, ailing for months now, had died in November, and word had soon spread that the new Sultan, the late king’s eighteen-year-old son, had no right to the throne. A bastard, an illegitimate upstart whom no self-respecting kingdom should accept as ruler, said many. Among those who had refused to acknowledge the new Sultan was Aurangzeb. A letter had arrived in Dilli from Aurangzeb to the Baadshah shortly after, and the Emperor’s response had been to give carte blanche to his son and his Diwan-i-kul: Deal as you feel fit with the situation.

And this was how they were dealing with it. Muzaffar sighed.

‘So they’re off to plunder Bijapur now? And how do they know it won’t be a repeat of Golconda? What if Bijapur also bribes Dara Shukoh and sends the Baadshah piles of diamonds, begging for mercy? To be pulled off from yet another invasion will do no good to the prestige of either the Shahzada or the Diwan-i-kul.’ His voice rose in agitation.

Akram held up a hand, gesturing to quieten Muzaffar. Two men sitting on a mattress nearby were staring, curious.

Muzaffar shrugged. ‘Ah, well. Perhaps some good will come of it. Who knows?’ He lifted the edge of the mattress, wiped the dirty blade of his knife surreptitiously on the underside, and replaced the knife in his boot. ‘Don’t tell me the Diwan-i-kul has ordered Abdul Munim Khan Sahib to accompany him to Aurangabad.’

Akram shook his head at the mention of his father, a venerable old amir. ‘No, of course not. Abba has never been any good as a soldier; he’d be a liability on the field, and he knows it. So does the Diwan-i-kul. No, he’s just got Abba to come up to Agra with him, because he wants to meet Mumtaz Hassan Khan.’ Akram noticed the blank look on his friend’s face and grinned. ‘You have no idea whom I’m talking about, do you?’ He paused, waiting for Muzaffar to say something, then carried on.

‘Mumtaz Hassan Khan is an amir who came to Agra from Bijapur years ago. His fortune was made in precious stones; primarily diamonds, but just about everything else too. He’s well-respected, extremely wealthy, and – as luck would have it – married to Abba’s half-sister. My uncle, so to say.’

Akram sniffled and peered into his cup. ‘In the few months the Diwan-i-kul has spent in Dilli, he hasn’t lost his touch,’ Akram said in a voice so low that Muzaffar had to lean forward to listen. ‘He appears to regard bribery as the most dependable means of conquest. They say he’s had it already put about in the armies of Bijapur that any officer who defects, along with a hundred men, will be given two thousand rupees. Underhand, but that’s the way he works. And he thinks Mumtaz Hassan Khan will be able to help him.’

‘Why?’

‘Because Hassan Sahib is still well liked and respected in Bijapur. He has contacts, and people will listen to him. Many of the wealthiest and most influential men of Bijapur – the diamond traders, the ministers, the big landowners – will pay heed if my uncle suggests that it would be a good idea to throw in their lot with the armies of the Shahzada and the Diwan-i-kul. Not all of them will agree, but the Diwan-i-kul seems to think most will. Enough, at any rate, to tilt the balance.’

‘So what is he planning to do? Take your uncle along with him to Aurangabad and then to Bijapur?’

Akram shrugged expressively. ‘I suppose so; Abba hasn’t thought it fit to take me that far into his confidence. I’d think the Diwan-i-kul might need to exert himself a bit to first bring my uncle around to his way of thinking. They’ve known each other a long time – I’d even say they were more friends than mere acquaintances. And Mumtaz Hassan is loyal enough to the Baadshah. But I’m not sure he’d be willing to stoop to bribery of the sort Mir Jumla wants to incite him to.’ He tipped back the cup, then put it down and regarded the dregs glumly before looking up at Muzaffar pleadingly. ‘Do visit us at the haveli, Muzaffar. I’m bored to death. The Diwan-i-kul, Abba and Mumtaz Hassan are closeted in the dalaan all day long, and the only other people in the haveli are the servants or the women in the zenana.’

Muzaffar allowed a half-smile of sympathy to flicker across his face. ‘So how do you spend your time?’

‘Going to the nakhkhas and trying out different mounts. Wandering around Kinari Bazaar. Touring the sites and gawping appreciatively at everything I see, just so I don’t look out of place.’

This time, Muzaffar grinned broadly. ‘And what, may I ask, have you been gawping at, that wasn’t worthy of your admiration?’

Akram’s eyes twinkled. ‘Nothing, I suppose. I went to Sikandra, to Bihishtabad. And through the gardens on the east bank of the river. I even went to the tomb of Itimad-ud-Daulah. Abba had known the man years ago, when he wielded a lot of power.’

Muzaffar nodded absently. Itimad-ud-Daulah, ‘Pillar of the State’ – for that was what the title meant – had not been merely a powerful nobleman, but had also eventually been successful in building a connection, by marriage, with the Emperor himself. Itimad-ud-Daulah’s accomplished and beautiful daughter Mehrunissa had married Shahjahan’s late father, the Emperor Jahangir; and had, in one fell swoop, not just made herself the most influential woman in the empire, but had also cleared the path for her family. Jahangir had bestowed on her the title Nur Mahal – Light of the Palace – and had later elevated her even further, by naming her Nur Jahan, Light of the World. Nur Jahan’s niece, Itimad-ud-Daulah’s granddaughter by his son, had been born Arjumand Bano Begum, but had, after her marriage to Shahjahan, become known as Mumtaz Mahal. The lady for whom a grieving husband, an unwarrantedly extravagant emperor and an unabashed aesthete, had built the most magnificent tomb in Agra – perhaps in all the world.

‘Have you been to the Taj Mahal?’ Muzaffar asked.

‘Of course I have. I’m nothing if not fashionable, Muzaffar, you know that. And going to the Taj Mahal is extremely fashionable. Have you been?’

‘Not since it was in the process of being built.’ Muzaffar’s mouth curled in a half-humorous, half-regretful smile. ‘It’s strange, you know; I have so much in common with Gauhar Ara Begum. We were both born in the same year, and we both lost our mothers soon after. Ammi’s grave is of course a paltry one compared to the Empress’s…’ His voice petered out. Akram looked on silently. After a moment, Muzaffar continued. ‘Zeenat Aapa and Khan Sahib brought me up, but Khan Sahib was constantly on the move: this year Lahore, the next Gwalior; then in the Deccan, and then off to Kashmir. When I look back at my childhood, it seems a whirlwind of long caravan trails, and of tented camps and Khan Sahib imparting lessons to me on horseback.’

‘And you acquiring a menagerie of small pets,’ added Akram with amusement as he recalled a long-ago confession of his friend’s.

‘That too.’ Muzaffar gulped down the last of his now tepid coffee. ‘And we seemed to be in Agra only now and then – on our way from one outpost to another. I saw the Taj Mahal rise, but in occasional glimpses. One year we passed through Agra, and they were excavating the land for the foundations and carrying away cartloads of earth. There was a yawning maw alongside the river, where they were digging deep shafts and sinking boxes of wood. Zeenat Aapa forbade me to go anywhere near the site; she was terrified I’d fall in.’

‘I saw the rauza – the cenotaph itself, not the mosque or the other subsidiary buildings that surround it – when it was all brick. They didn’t put in the white marble cladding till later, and frankly, I couldn’t imagine then what it would look like. Somehow, that vast building all in brick didn’t inspire any admiration in me.’ He smiled ruefully. ‘Then one year they were building the mosque. There was that Persian calligrapher, Amanat Khan, creating his paper prototypes for the verses that were going to be inscribed all across.’ His eyes brightened perceptibly as a thought struck him. ‘What I liked best was when Khan Sahib took me to see the stone cutters at work. I’d seen tulips and daffodils in Kashmir, but never in Agra – and these men were creating them, slicing the gemstones and carving the marble, inlaying flowers. I’d never seen anything like it before. I still haven’t.’

‘You must see the finished work for yourself,’ Akram said fervently. ‘It’s spectacular. And you must meet my uncle, Mumtaz Hassan. He was one of the purveyors for the gemstones used at the Taj Mahal. I’m sure he’ll have some interesting stories to tell.’

ABBAS QURESHI, THE uncle of the young lady whom Muzaffar had found himself escorting to Ajmer, was a minor amir with a haveli tucked away on the western bank of the Yamuna. All the powerful noblemen, the mansabdars with their huge endowments, their vast households and dozens of servants, had their havelis – each competing with the next for grandeur – along the western bank, between the fort and the luminous Taj Mahal. The Taj Mahal, also known as the Taj Bibi, had itself been built on land acquired from a nobleman, the Raja of Amber. The raja had been amply compensated for his bequest; he had received not one, but four separate stretches of land in return.

The chances of anybody ever requesting Abbas Qureshi for any of his land were slim. His haveli was a modest one, the white marble cladding of the dalaan its only attempt at ostentation. The rest of the mansion was affordable brick, plastered over and polished. It was a neat house, clean and airy, and with a small khanah bagh – a private garden – where the women and children could come out for a breath of fresh air. In the dead of winter, with a chill breeze blowing in from across the river, the inhabitants of the zenana remained indoors, huddled under their light quilts and wrapped in their fine shawls. Zeenat Begum, Muzaffar’s elder sister and adoptive mother, had taken advantage of the emptiness of the khanah bagh. A tersely worded note had been presented to Muzaffar by one of the eunuchs from the zenana. Muzaffar was to present himself at the khanah bagh an hour after lunch.

Zeenat was already seated on the single stone bench when Muzaffar entered the garden. Her eyes lit up when she saw him, and she rose to her feet, gathering her shawls about her. Her thin face, with wisps of grey hair escaping from below the dupatta covering her head, was still attractive. The smile as she came towards Muzaffar and reached out to take his hand made it more so. ‘Thank you for coming,’ she said, moving back to the bench, with Muzaffar following in her wake. ‘I’d wondered if you’d come.’

‘You didn’t give me much choice, Aapa,’ Muzaffar said, with an affectionate grin. ‘That note told me to come; you didn’t say I was allowed to refuse.’ He lowered himself beside her onto the bench, careful not to step on the silken skirt of her flowing ankle-length jagulfi, its fitted sleeves and fine bodice hidden beneath a flowing qaba, a long gown of pashmina.

‘Have you bought yourself a new horse, as you said you would?’ she asked as she stroked the qaba down with long, slender fingers, luxuriating in the feel of the soft wool.

Muzaffar told her of the unexpected meeting with Akram. ‘I thought I’d return to the nakhkhas tomorrow, perhaps,’ he explained. ‘But at lunch today, Qureshi Sahib was strangely magnanimous. He insisted that while I am in Agra, and until my

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...