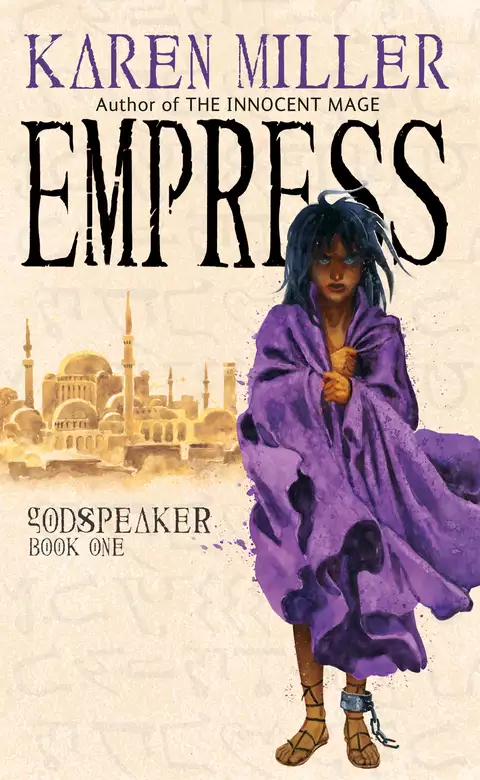

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

In a family torn apart by poverty and violence, Hekat is no more than an unwanted mouth to feed, worth only a few coins from a passing slave trader.

But Hekat was not born to be a slave. For her, a different path has been chosen. It is a path that will take her from stinking back alleys to the house of her God, from blood-drenched battlefields to the glittering palaces of Mijak.

This is the story of Hekat, slave to no man.

Release date: April 1, 2008

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 752

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Empress

Karen Miller

Despite its two burning lard-lamps the kitchen was dark, its air choked with the stink of rancid goat butter and spoiling goat-meat. Spiders festooned the corners with sickly webs, boarding the husks of flies and suck-you-dries. A mud-brick oven swallowed half the space between the door and the solitary window. There were three wooden shelves, one rickety wooden stool and a scarred wooden table, almost unheard of in this land whose trees had ages since turned to stone.

Crouched in the shadows beneath the table, the child with no name listened to the man and the woman fight.

“But you promised,” the woman wailed. “You said I could keep this one.”

The man’s hard fist pounded the timber above the child’s head. “That was before another poor harvest, slut, before two more village wells dried up! All the coin it costs to feed it, am I made of money? Don’t you complain, when it was born I could’ve thrown it on the rocks, I could’ve left it on The Anvil!”

“But she can work, she—”

“Not like a son!” His voice cracked like lightning, rolled like thunder round the small smoky room. “If you’d whelped me more sons—”

“I tried!”

“Not hard enough!” Another boom of fist on wood. “The she-brat goes. Only the god knows when Traders will come this way again.”

The woman was sobbing, harsh little sounds like a dying goat. “But she’s so young.”

“Young? Its blood-time is come. It can pay back what it’s cost me, like the other she-brats you spawned. This is my word, woman. Speak again and I’ll smash your teeth and black your eyes.”

When the woman dared disobey him the child was so surprised she bit her fingers. She scarcely felt the small pain; her whole life was pain, vast like the barren wastes beyond the village’s godpost, and had been so since her first caterwauling cry. She was almost numb to it now.

“Please,” the woman whispered. “Let me keep her. I’ve spawned you six sons.”

“It should’ve been eleven!” Now the man sounded like one of his skin-and-bone dogs, slavering beasts who fought for scraps of offal in the stony yard behind their hovel.

The child flinched. She hated those dogs almost as much as she hated the man. It was a bright flame, her hatred, hidden deep and safe from the man’s sight. He would kill her if he saw it, would take her by one skinny scabbed ankle and smash her headfirst into the nearest red and ochre rock. He’d done it to a dog once, that had dared to growl at him. The other dogs had lapped up its brains then fought over the bloody carcass all through the long unheated night. On her threadbare blanket beneath the kitchen table she’d fallen asleep to the sound of their teeth, and dreamed the bones they gnawed were her own.

But dangerous or not she refused to abandon her hate, the only thing she owned. It comforted and nourished her, filling her ache-empty belly on the nights she didn’t eat because the woman’s legs were spread, or her labors were unfinished, or the man was drunk on cactus blood and beating her.

He was beating her now, open-handed blows across the face, swearing and sweating, working himself to a frenzy. The woman knew better than to cry out. Listening to the man’s palm smack against the woman’s sunken cheeks, to his lusty breathing and her swallowed grunts, the child imagined plunging a knife into his throat. If she closed her eyes she could see the blood spurt scarlet, hear it splash on the floor as he gasped and bubbled and died. She was sure she could do it. Hadn’t she seen the men with their proud knives cut the throats of goats and even a horse, once, that had broken its leg and was no longer good for anything but meat and hide and bleached boiled bones?

There were knives in a box on the kitchen’s lowest shelf. She felt her fingers curl and cramp as though grasping a carved bone hilt, felt her heart rattle her ribs. The secret flame flickered, flared . . . then died.

No good. He’d catch her before she killed him. She would not defeat the man today, or tomorrow, or even next fat godmoon. She was too small, and he was too strong. But one day, many fat godmoons from now, she’d be big and he’d be old and shrunken. Then she’d do it and throw his body to the dogs after and laugh and laugh as they gobbled his buttocks and poked their questing tongues through the empty eye sockets of his skull.

One day.

The man hit the woman again, so hard she fell to the pounded dirt floor. “You poisoned my seed five times and whelped bitches, slut. Three sons you whelped lived less than a godmoon. I should curse you! Turn you out for the godspeaker to deal with!”

The woman was sobbing again, scarred arms crossed in front of her face. “I’m sorry—I’m sorry—”

Listening, the child felt contempt. Where was the woman’s flame? Did she even have one? Weeping. Begging. Didn’t she know this was what the man wanted, to see her broken and bleating in the dirt? The woman should die first.

But she wouldn’t. She was weak. All women were weak. Everywhere in the village the child saw it. Even the women who’d spawned only sons, who looked down on the ones who’d spawned she-brats as well, who helped the godspeaker stone the cursed witches whose bodies spewed forth nothing but female flesh . . . even those women were weak.

I not weak the child told herself fiercely as the man soaked the woman in venom and spite and the woman wept, believing him. I never beg.

Now the man pressed his heel between the woman’s dugs and shoved her flat on her back. “You should pray thanks to the god. Another man would’ve broke your legs and turned you out seasons ago. Another man would’ve plowed two hands of living sons on a better bitch than you!”

“Yes! Yes! I am fortunate! I am blessed!” the woman gabbled, rubbing at the bruised place on her chest.

The man shucked his trousers. “Maybe. Maybe not. Spread, bitch. You give me a living son nine fat godmoons from now or I swear by the village godpost I’ll be rid of you onto The Anvil!”

Choking, obedient, the woman hiked up her torn shift and let her thin thighs fall open. The child watched, unmoved, as the man plowed the woman’s furrow, grunting and sweating with his effort. He had a puny blade, and the woman’s soil was old and dusty. She wore her dog-tooth amulet round her neck but its power was long dead. The child did not think a son would come of this planting or any other. Nine fat godmoons from this day, or sooner, the woman would die.

His seed at last dribbled out, the man stood and pulled up his trousers. “Traders’ll be here by highsun tomorrow. Might be seasons till more come. I paid the godspeaker to list us as selling and put a goat’s skull on the gate. Money won’t come back, so the she-brat goes. Use your water ration to clean it. Use one drop of mine. I’ll flay you. I’ll hang you with rope twisted from your own skin. Understand?”

“Yes,” the woman whispered. She sounded tired and beaten. There was blood on the dirt between her legs.

“Where’s the she-brat now?”

“Outside.”

The man spat. He was always spitting. Wasting water. “Find it. When it’s clean, chain it to the wall so it don’t run like the last one.”

The woman nodded. He’d broken her nose with his goat-stick that time. The child, three seasons younger then, had heard the woman’s splintering bone, watched the pouring blood. Remembering that, she remembered too what the man did to the other she-brat to make it sorry for running. Things that made the she-brat squeal but left no mark because Traders paid less for damaged goods.

That she-brat had been a fool. No matter where the Traders took her it had to be better than the village and the man. Traders were the only escape for she-brats. Traders . . . or death. And she did not want to die. When they came for her before highsun tomorrow she would go with them willingly.

“I’ll chain her,” the woman promised. “She won’t run.”

“Better not,” growled the man, and then the slap of goathide on wood as he shoved the kitchen door aside and left.

The woman rolled her head until her red-rimmed eyes found what they sought beneath the kitchen table. “I tried. I’m sorry.”

The child crawled out of the shadows and shrugged. The woman was always sorry. But sorrow changed nothing, so what did it matter? “Traders coming,” she said. “Wash now.”

Wincing, breath catching raw in her throat, the woman clutched at the table leg and clawed herself to her knees, then grabbed hold of the table edge, panting, whimpering, and staggered upright. There was water in her eyes. She reached out a work-knotted hand and touched rough fingertips to the child’s cheek. The water trembled, but did not fall.

Then the woman turned on her heel and went out into the searing day. Not understanding, not caring, the child with no name followed.

The Traders came a finger before highsun the next day. Not the four from last time, with tatty robes, skinny donkeys, half-starved purses and hardly any slaves. No. These two Traders were grand. Seated on haughty white camels, jangling with beads and bangles, dangling with earrings and sacred amulets, their dark skin shiny with fragrant oils and jeweled knife-sheaths on their belts. Behind them stretched the longest snake-spine of merchandise: men’s inferior sons, discarded, and she-brats, and women. All naked, all chained. Some born to slavery, others newly sold. The difference was in their godbraids, slaves of long standing bore one braid of deep blood red, a sign from the god that they were property. The new slaves would get their red braids, in time.

Guarding the chained slaves, five tall men with swords and spears. Their godbraids bore amulets, even their slave-braids were charmed. They must be special slaves, those guards. In the caravan there were pack camels too, common brown, roped together, laden with baskets, criss-crossed with travel-charms. A sixth unchained slave led them, little more than a boy, and his red godbraid bore amulets as well. At his signal, groaning, the camels folded their calloused knees to squat on the hard ground. The slaves squatted too, silent and sweating.

Waiting in her own chains, the crude iron links heavy and chafing round her wrists and ankles, the child watched the Traders from beneath lowered lashes as they dismounted and stood in the dust and dirt of the man’s small holding. Their slender fingers smoothed shining silk robes, tucked their glossy beaded godbraids behind their ears. Their fingernails were all the same neat oval shape and painted bright colors to match their clothing: green and purple and crimson and gold. They were taller than the tallest man in the village. Taller than the godspeaker, who must stand above all. One of them was even fat. They were the most splendid creatures the child had ever seen, and knowing she would leave with them, leave forever the squalor and misery of the man and the village, her heart beat faster and her own unpainted fingernails, ragged and shapeless, bit deep into her dirty scarred palms.

The Traders stared at the cracked bare ground with its withered straggle of weeds, at the mud brick hovel with its roof of dried grasses badly woven, at the pen of profitless goats, at the man whose bloodshot eyes shone with hope and avarice. A look flowed between them and their plump lips pursed. They were sneering. The child wondered where they came from, to be so clean and disapproving. Somewhere not like this. She couldn’t wait to see such a place herself, to sleep for just one night inside walls that did not stink of fear and goat. She’d wear a hundred chains and crawl on her hands and knees across The Anvil’s burning sand if she had to, so long as she reached it.

The man was staring at the Traders too, his eyes popping with amazement. He bobbed his head at them, like a chicken pecking corn. “Excellencies. Welcome, welcome. Thank you for your custom.”

The thin Trader wore thick gold earrings; tattooed on his right cheek, in brightest scarlet, a stinging scorpion. The child bit her tongue. He had money enough to buy a protection like that? And power enough that a godspeaker would let him? Aieee . . .

He stepped forward and looked down at the man, fingertips flicking at her. “Just this?”

She was enchanted. His voice was deep and dark like the dead of night, and shaped the words differently from the man. When the man spoke it sounded like rocks grinding in the dry ravine, ugly like him. The Trader was not ugly.

The man nodded. “Just this.”

“No sons, un-needed?”

“Apologies, Excellency,” said the man. “The god has granted me few sons. I need them all.”

Frowning, the Trader circled the child in slow, measured steps. She held her breath. If he found her unpleasing and if the man did not kill her because of it, she’d be slaved to some village man for beating and spawning sons and hard labor without rest. She would cut her flesh with stone and let the dogs taste her, tear her, devour her, first.

The Trader reached out his hand, his flat palm soft and pink, and smoothed it down her thigh, across her buttock. His touch was warm, and heavy. He glanced at the man. “How old?”

“Sixteen.”

The Trader stopped pacing. His companion unhooked a camel whip from his belt of linked precious stones and snapped the thong. The man’s dogs, caged for safety, howled and threw themselves against the woven goathide straps of their prison. In the pen beside them the man’s goats bleated and milled, dropping anxious balls of shit, yellow slot-eyes gleaming.

“How old?” the Trader asked again. His green eyes were narrow, and cold.

The man cringed, head lowered, fingers knuckled together. “Twelve. Forgive me. Honest error.”

The Trader made a small, disbelieving sound. He’d done something to his eyebrows. Instead of being a thick tangled bar like the man’s they arched above his eyes in two solid gold half-circles. The child stared at them, fascinated, as the Trader leaned down and brought his dark face close to hers. She wanted to stroke the scarlet scorpion inked into his cheek. Steal some of his protection, in case he did not buy her.

His long, slender fingers tugged on her earlobes, traced the shape of her skull, her nose, her cheeks, pushed back her lips and felt all her teeth. He tasted of salt and things she did not know. He smelled like freedom.

“Is she blooded?” he asked, glancing over his shoulder at the man.

“Since four godmoons.”

“Intact?”

The man nodded. “Of course.”

The Trader’s lip curled. “There is no ‘of course’ where men and she-flesh abide.”

Without warning he plunged his hand between her legs, fingers pushing, probing, higher up, deeper in. Teeth bared, her own fingers like little claws, the child flew at him, screeching. Her chains might have weighed no more than the bangles on his slender, elegant wrists. The man sprang forward shouting, fists raised, face contorted, but the Trader did not need him. He brushed her aside as though she were a corn-moth. Seizing a handful of black and tangled hair he wrenched her to the tips of her toes till she was screaming in pain, not fury, and her hands fell limply by her sides. She felt her heart batter her brittle ribs and despair storm in her throat. Her eyes squeezed shut and for the first time she could remember felt the salty sting of tears.

She had ruined everything. There would be no escape from the village now, no new life beyond the knife-edged horizon. The Trader would toss her aside like spoiled meat, and when he and his fat friend were gone the man would kill her or she would be forced to kill herself. Panting like a goat in the slaughter-house she waited for the blow to fall.

But the Trader was laughing. Still holding her, he turned to his friend. “What a little hell-cat! Untamed and savage, like all these dwellers in the savage north. But do you see the eyes, Yagji? The face? The length of bone and the sleekness of flank? Her sweet breasts, budding?”

Trembling, she dared to look at him. Dared to hope . . .

The fat one wasn’t laughing. He shook his head, setting the ivory dangles in his ears to swinging. “She is scrawny.”

“Today, yes,” agreed the Trader. “But with food and bathing and three times three godmoons . . . then we shall see!”

“Your eyes see the invisible, Aba. Scrawny brats are oft diseased.”

“No, Excellency!” the man protested. “No disease. No pus, no bloating, no worms. Good flesh. Healthy flesh.”

“What there is of it,” said the Trader. He turned. “She is not diseased, Yagji.”

“But she is ill-tempered,” his fat friend argued. “Undisciplined, and wild. She’ll be troublesome, Aba.”

The Trader nodded. “True.” He held out his hand and easily caught the camel whip tossed to him. Fingers tight in her hair he snapped the woven hide quirt around her naked legs so the little metal weights on its end printed bloody patterns in her flesh.

The blows stung like fire. The child sank her teeth into her lip and stared unblinking into the Trader’s careful, watching eyes, daring him to strip the unfed flesh from her bones if he liked. He would see she was no weakling, that she was worthy of his coin. Hot blood dripped down her calf to tickle her ankle. Within seconds the small black desert flies came buzzing to drink her. Hearing them, the Trader withheld the next blow and instead tossed the camel whip back to its owner.

“Lesson one, little hell-cat,” he said, his fingers untangling from her hair to stroke the sharp line of her cheek. “Raise your hand or voice to me again and you will die never knowing the pleasures that await you. Do you understand me?”

The black desert flies were greedy, their eager sucking made her skin crawl. She’d seen what they could do to living creatures if not discouraged. She tried not to dance on the spot as the feverish flies quarreled over her bloody welts. All she understood was the Trader did not mean to reject her. “Yes.”

“Good.” He waved the flies away, then pulled from his gold and purple pocket a tiny pottery jar. When he took off its lid she smelled the ointment inside, thick and rich and strange.

Startling her, he dropped to one knee and smeared her burning legs with the jar’s fragrant paste. His fingers were cool and sure against her sun-seared skin. The pain vanished, and she was shocked. She hadn’t known a man could touch a she-brat and not hurt it.

It made her wonder what else she did not know.

When he was finished he pocketed the jar and stood, staring down at her. “Do you have a name?”

A stupid question. She-brats were owed no names, no more than the stones on the ground or the dead goats in the slaughter-house waiting to be skinned. She opened her mouth to say so, then closed it again. The Trader was almost smiling, and there was a look in his eyes she’d never seen before. A question. Or a challenge. It meant something. She was sure it meant something. If only she could work out what . . .

She let her gaze slide sideways to the mud brick hovel and its mean kitchen window, where the woman thought she could not be seen as she dangerously watched the trading. The woman who had no name, just descriptions. Bitch. Slut. Goatslit. Then she looked at the man, shaking with greed, waiting for his money. If she gave herself a name, how angry it would make him.

But she couldn’t think of one. Her mind was blank sand, like The Anvil. Who was she? She had no idea. But the Trader had named her, hadn’t he? He had called her something, he had called her—

She tilted her chin so she could look into his green and gleaming eyes. “He—kat,” she said, her tongue stumbling over the strange word, the sing-song way he spoke. “Me. Name. Hekat.”

The Trader laughed again. “As good a name as any, and better than most.” He held up his hand, two fingers raised; his fat friend tossed him a red leather pouch, clinking with coin.

The man stepped forward, black eyes ravenous. “If you like the brat so much I will breed you more! Better than this one, worth twice as much coin.”

The Trader snorted. “It is a miracle you bred even this one. Do not tempt the god with your blustering lest your seed dry up completely.” Nostrils pinched, he dropped the pouch into the man’s cupped hands.

The man’s fingers tore at the pouch’s tied lacing, so clumsily that its contents spilled on the ground. With a cry of anguish he plunged to his knees, heedless of bruises, and began scrabbling for the silver coins. His knuckles skinned against the sharp stones but the man did not notice the blood, or the buzzing black flies that swarmed to drink him.

For a moment the Trader watched him, unspeaking. Then he trod the man’s fingers into the dirt. “Your silver has no wings. Remove the child’s chains.”

The man gaped, face screwed up in pain. “Remove . . . ?”

The Trader smiled; it made his scarlet scorpion flex its claws. “You are deaf? Or would like to be?”

“Excellency?”

The Trader’s left hand settled on the long knife at his side. “Headless men cannot hear.”

The man wrenched his fingers free and lurched to his feet. Panting, he unlocked the binding chains, not looking at the child. The skin around his eyes twitched as though he were scorpion-stung.

“Come, little Hekat,” said the Trader. “You belong to me now.”

She followed him to the waiting slave train, thinking he would put his own chains about her wrists and ankles and join her to the other naked slaves squatting on the ground. Instead he led her to his camel and turned to his friend. “A robe, Yagji.”

The fat Trader Yagji sighed and fetched a pale yellow garment from one of the pack camel’s baskets. Barely breathing, the child stared as the thin Trader took his knife and slashed through the cloth, reducing it to fit her small body. Smiling, he dropped the cut-down robe over her head and guided her arms into its shortened sleeves, smoothed its cool folds over her naked skin. She was astonished. She wished the man’s sons were here to see this but they were away at work. Snake-dancing, and tending goats.

“There,” said the Trader. “Now we will ride.”

Before she could speak he was lifting her up and onto the camel.

Air hissed between the fat Trader’s teeth. “Ten silver pieces! Did you have to give so much?”

“To give less would be insulting to the god.”

“Tcha! This is madness, Abajai! You will regret this, and so will I!”

“I do not think so, Yagji,” the thin Trader replied. “We were guided here by the god. The god will see us safe.”

He climbed onto the camel and prodded it to standing. With a muffled curse, the fat Trader climbed onto his own camel and the slave train moved on, leaving the man and the woman and the goats and the dogs behind them.

Hekat sat on the Trader’s haughty white camel, her head held high, and never once looked back.

CHAPTER TWO

As the village and its splintered, weathered wooden godpost dwindled into the heat-hazed distance behind them the thin Trader Abajai said, his hand warm and secure on Hekat’s shoulder, “The others we purchased. Do you know them?”

He and fat Yagji had bought four more villagers after leaving the man’s holding. A woman, another she-brat and two boys. Unlike her, they walked with the rest of the slaves, chained to them and to each other, guarded by the five tall slaves with spears. Sitting before Abajai on his white camel, with its coarse hair tickling her bare legs, she shook her head. “No. Hekat knows man. Woman. Man’s sons.” A shiver rippled over her skin. “Godspeaker.”

“No-one else? You had no friends?” said Abajai. “Who will you weep for tonight, Hekat?”

She shrugged. “Hekat not weep.”

Riding beside them. Yagji sighed. “Must you talk to it, Aba? It’s not a pet.”

Abajai chuckled. “I’ve heard you talk to your monkey.”

She looked over her shoulder at him. “Monkey?”

“An animal. Smelly, noisy, greedy.” He smiled. “Yagji will introduce you when we reach Et-Raklion.”

“I won’t,” said Yagji. “She will teach little Hooli bad manners. Abajai, you should sell this one before we get home.” A red stone carved into a single staring eye dangled on a chain around his neck; he clutched it with plump fingers. “There is a darkness . . .”

“Superstition,” Abajai grunted. “The god desired us to find this one, Yagji. You worry for nothing. We will reach Et-Raklion.”

Hekat frowned. “Et-Raklion?”

“Our home.”

“Where?”

Abajai pointed ahead, to where the ground met the sky. “Further than your eye can see, Hekat. Many godmoons traveling beyond the horizon.”

She shook her head. That place was so far away she couldn’t imagine it. Already she was lost. The barren land stretched on every side, dressed in all its hot colors: red, orange, ochre, brown. Spindle grass withered beneath the uncovered sun, dull purple, dying green. The sky was a heavy palm pressing her flat towards the slow-baked ground. Beneath the padding of camel-feet, the clanking of slave-chains, the clicking of rock against pebble, silence waited like a sandcat poised to smother and kill. If she wasn’t careful, she’d forget how to breathe.

Abajai’s hand returned to her shoulder. “Fear not, Hekat. You are safe with me.”

“Safe?”

Beside them, Yagji tittered. “He may be a monkey but at least my little Hooli understands more than one word in five!”

Abajai ignored him. “Yes, Hekat. Safe. That means I will protect you.” His fingers had tightened a little, and his voice was gentle. The wonder of that was as crushing as the sky. “No hurting. No hunger. Safe.”

She became one with the silence. In the village no she-brat was safe. Not from the man, or his sons, or the godspeaker who stalked the streets like a vulture, always looking for sin to stone.

“Safe,” she whispered at last. The white camel flicked its ear at her, grumbling softly as it walked. She looked back at the Trader. “Safe Et-Raklion?”

He smiled widely at her, teeth blinding. Tiny gemstones sparkled, blue and red and green. She gasped, and touched her own teeth in amazement. She had not noticed his gemstones in the village. Abajai laughed. “You like them?” She nodded. “You wish for some of your own?”

Fat Yagji moaned like a woman. “Aba, I beg you! Protections in your teeth is one thing. It’s proper. But in her mouth? The waste!”

“Perhaps,” said Abajai, shrugging. “But I will buy her an amulet in Todorok. Other eyes are not blind, Yagji. They will see what you cannot.”

“Yes, yes, they’ll see,” grumbled the fat Trader, like a camel. “They’ll see you’re godforsaken!”

Laughing, Abajai waved away an obstinate fly. “With this prize? Yagji, kiss your eye for blasphemy.”

Yagji didn’t kiss his red stone eye, but he touched it again. “You tempt the god to smiting, Aba. Boast less. Pray more.”

Hekat sighed. Words, words, buzz buzz buzz. “Abajai.” He’d said she could use his name. “Tell Hekat Et-Raklion.”

“Don’t,” said Yagji. “She will see it soon enough.”

“She can barely utter a civilized sentence, Yagji,” said Abajai. “If I do not speak with her how will she learn?” He patted her shoulder. “Et-Raklion is a mighty city, Hekat.”

“City?”

He held his arms wide. “A big, big, big village. You know big?”

She nodded. “Yes. Big not village. Hekat village small.”

His sparkly teeth flashed again. “She is not stupid, Yagji. Underfed, yes, and starved of learning. But in no way is she stupid.”

Yagji threw up his hands. “And this is good, Aba? Intelligent slaves are good? Aieee! May the god protect us!”

The talking stopped then. In silence they traveled away from the sliding sun, chased the long thin shadows it cast down the red rock ground before them. Abajai was like the god, he knew where to ride even though the land was empty. Hekat felt her eyes drift closed, her head nod like a wilting weed on its stem. Abajai’s hand rested on her shoulder. She would not fall. She was safe. She slept.

When he shook her awake the blue sky had faded. It was dusk, and little pricky stars sparkled like the gemstones in his teeth. The godmoon and his wife were risen, small silver discs against the deepening dark. The white camels lifted their heads, snuffling, then slowed, stopped and settled on the ground.

“This will do,” said Abajai, sliding from his saddle. “Stake the slaves out, Obid,” he ordered the oldest and tallest of the guards. “Food and water.”

“How much, master?” said Obid. “That village was poor. Supplies are low and no hunting here.”

Abajai looked around them at the sun-killed plain. “A fist of grain, a cup of water, night and dawn till my word changes. In twenty highsuns we’ll reach Todorok village and trade for fresh supplies. What we have will last until then.”

Hekat felt her eyes go wide. Twenty highsuns? So far away! Had any man in the village ever traveled so far? She did not think so.

While Obid and the other guards settled the slaves and camels for the night, Abajai and Yagji unpacked baskets and sacks. She watched for a moment, aware of a growing discomfort. She jiggled, looking around. There was nothing to squat behind. Yagji noticed. He stopped unpacking and tugged at Abajai’s sleeve.

“Hekat?” said Abajai.

“Need lose water.”

“Pish, you mean?”

Did she? Guessing, she nodded. “Need lose water now.”

He went to his white camel, opened one of its carry baskets and pulled out a small clay pot. “Pish into this and give it to Obid.”

To Obid? She stared. “Obid want body water?”

“I want it.” When he saw she still didn’t understand, he said, “Your village. Do the people keep body water?”

“For goat leather. No goats, Abajai.”

“No, but we turn our body water into coin when other villages need more. Pish now, Hekat. We must make camp.”

So she pished, and gave the sloshing pot to Obid. He did not speak to her, just poured her water into a big clay jar unstrapped from the sturdiest pack camel. As she walked away she felt the chained slaves’ gazes sliding sideways over her skin, wondering and jealous.

Let them wonder. Let them hate. She did not care for them.

After pishing, tired and sore from camel-riding, she yawned cross-legged on the blanket Abajai gave her, amazed as the Traders produced rolls of colored cloth from the pack camels’ baskets and turned them into little rooms.

“Tents,” said Abajai, seeing her surprise. “You will sleep in mine.”

There was food in the white camels’ baskets, better than the slaves were eating. Better than any food she’d smelled in her life. Yagji made a fire with bricks of dried camel-dung and warmed the food in an iron pot over the flames, adding leaves she didn’t recognize. He kept them in little shiny boxes and talked to himself as he pinched some from this one, some from that. Yagji was strange. As the food slowly heated, releasing such smells, her belly turned over and over and she almost choked on the juices flooding her mouth.

“Don’t snatch,” said Abajai as he handed her a pottery bowl filled halfway, and a spoon. His knuckles rapped hard on her head. “Dignity. Restraint. Conduct. You must learn these things.”

She didn’t know those words. All she knew was she’d displeased him. For the second time that day salty water stung her eyes.

“Tchut tchut tchut,” he soothed her, no knuckles now, just a gentle pat to her cheek. “Eat. Slowly. I will fetch you drink. You know sadsa?”

Mouth stuffed full of meat, aieee, so wonderful, she shook her head, watching as he took an empty bronze cup and filled it from a leather flask. Yagji nodded. “Good idea,” he said. “If you insist on having it in your tent, best it be well fuddled.”

Abajai shook his head. “Hekat is no danger.”

“You say.”

“The god says,” Abajai replied, frowning.

Yagji put down his own bowl and rummaged through the leather bag that held his little boxes of leaves. “Best be safe than sorry,” he said, tossing him a small yellow pouch.

Abajai rolled his eyes, but he took some blue powder from the pouch, dropped it in the bronze cup and swirled. Then he tossed the pouch back to Yagji and gave her the cup. “Sadsa, Hekat. Drink.”

No man had ever served her before. Women served men, that was the way. Almost dreamy, she lifted the bronze cup to her nose. Sadsa was creamy white, and its sharp, sweet-sour smell tickled. There were tiny flecks of blue caught in its frothy surface. She looked at Yagji, not trusting him. “What?”

“Sadsa is camel’s milk,” said Abajai. “Good for you.”

He didn’t understand, so she pointed at the yellow pouch still caught in Yagji’s fingers. “What?”

Abajai laughed. “I told you, Yagji. Not stupid.” Bending, he patted her cheek again. “For sleeping, Hekat. It will not harm you. Drink.”

He had saved her from the man. He did not chain her naked with the slaves, he clothed her and let her ride before him on his fine white camel. She drank. The sadsa flowed down her throat and into her belly like soft fire. She gasped, choking. The dancing flames blurred. So did Yagji’s face, and Abajai’s. She put down the bronze cup and ate more meat. Her fingers felt clumsy, wrapped around the spoon. Too soon the bowl was empty. Hopefully, she looked at Abajai.

“No,” he said. “Your belly’s had enough surprise. Finish your sadsa, then you must sleep.”

By the time the cup was empty she could barely keep her eyes open. It slipped from her silly fat fingers to the ground, and rolled in little circles that made her laugh. Laughing made her laugh. What a stupid sound! The man didn’t like it, he’d hit her when she laughed. Laughing was for secret. For almost never. But Abajai wasn’t angry. He was smiling, his green eyes mysterious, and in the leaping firelight the jewels in his teeth were precious. The scarlet scorpion sat quietly in his skin, keeping him safe. She tried to stand but her legs had turned to grass. She lay on her back instead, staring at the pricky stars, and laughed even harder.

“Oh, put it to bed, Aba,” said Yagji crossly. “If this is what we’ve got to look forward to on the long road to Et-Raklion I doubt you and I will be speaking by the end.”

“Et-Raklion,” she sang to the godmoon and his wife. “Hekat go Et-Raklion. La la la la . . .”

Strong arms slid beneath her shoulders and her knees. Abajai lifted her as the god’s breath lifted dust. “See how the god smiles, Yagji?” he said. “She has a sweet song voice to match her face.”

Yagji said something she couldn’t understand, but it sounded rude. His upside-down face wore a rude look. Dangling backwards over Abajai’s arm, she pointed at it. “Funny Yagji make goat talk. Meh meh meh.”

Abajai lay her inside his tent on something soft and warm like a cloud of sunshine, and covered her in a blanket that didn’t scratch her skin.

“Sleep, Hekat,” he said.

“Abajai,” she sighed, and felt her lips curve as she fell headfirst into the warm dark. “Abajai.”

She woke in daylight from a bad dream about the man’s dogs, needing to lose water so badly her belly was cramping. Abajai snored, a long still shape beneath his striped wool blankets. Heart pounding from the dream she fumbled the tent-flap open and stumbled outside, where Obid and the other guards walked up and down the snake-spine of slaves, taking away their dirty wool blankets, making sure none had died in the night. They carried pots, and one by one the slaves squatted over them, losing water. Making coin for Abajai.

There was no time to ask for a pot of her own, hot trickles were tickling her thighs, so she moved away from the tent, hiked up the yellow robe Abajai had given her and let her own water flow. Obid saw her. Shoving the pot he carried at another guard he loped towards her, arms waving, lips peeled back over teeth like knife points, all stained red.

She staggered backwards, fingers clawed. “Abajai!”

He came out of the tent as Obid reached her with his hand swinging to smack her face. “Obid!” he shouted. “Hunta!”

Obid dropped to his knees like an axed goat, and pressed his forehead to the dirt. “Master.”

Abajai wore a dark green robe and carried a club with a knot on one end and plaited thongs at the other. He tossed it in the air, caught it again just above the knot and brought the thongs down hard across Obid’s bowed shoulders. Obid was wearing nothing but his loincloth. His light brown skin welted at once and he whimpered. Four more times Abajai struck him. Obid’s fingers spasmed, but he didn’t cry out.

“Stand,” said Abajai. He sounded calm, but stern. “See this one?”

Standing again, Obid looked at her. “Master.”

“This one may not be touched without my nod.”

Obid struggled for words. “Master, this one spilled its water on the ground.”

“Ah.” Abajai dropped to a crouch before her, the scarlet scorpion flexing its claws as he grimaced. “What did I tell you, Hekat?”

“Use pot.”

“If you don’t use a pot, you waste your water. That is the same as stealing my coin. You understand?”

She felt the cool newsun air catch in her throat. The godspeaker saved his second-sharpest rocks for stealers. “No steal, Abajai,” she said jerkily. “No time for pot. Need pish now.”

Abajai sighed. Behind him, Obid’s face was flat as stone. Only his pale blue eyes were alive, they were full of questions. “Hekat, you are precious. But if you close your ears to my word again I will give Obid my nod and he will beat you. Just like you were one of the slaves he guards. You understand?”

Hekat, you are precious. The words burst inside her like a rain cloud, rare and hardly looked for. She nodded, drenched with pleasure. “Yes, Abajai. Water in pot.”

His lips twitched. “All my words must be obeyed, Hekat. You understand?”

“Yes, Abajai.”

Supple as a snake, he rose to his feet. “Good. Obid?”

Obid stepped forward. “Master.”

Abajai rested a fingertip on her head. “Unless you receive my nod, this one is hidden from you.”

Now the questions in Obid’s eyes writhed like maggots in old meat. “Yes, master.”

“Go back to your business. We leave soon.”

Obid bowed. “Master.”

She watched Obid lope back to the slave line, where his fellow guards pretended not to watch. “Obid not like Hekat.”

Abajai looked down at her, faintly smiling. “Does Hekat care?”

She grinned. “No. Hekat not care.”

“Good,” he said. “It is foolish to care for the feelings of a slave. Now come.”

She returned with him to their camp, where Yagji was brewing tea and cooking corncakes in a pan. He was dressed in a white robe shot through with gold threads. All his godbraids were gathered in a tail at the base of his neck and he’d taken off his red stone eye. Now a green coiled snake dangled round his neck. The stone it was carved from was shiny, she’d never seen anything like it before.

“More trouble, Aba?” he said sourly as she settled on a blanket and watched Abajai portion out food and drink for two.

“No,” said Abajai, handing her a plate and cup. Then he picked up a jug and held it over her corncakes. “Honey?”

“What honey?”

“What is honey,” he corrected. “You must learn proper Mijaki, Hekat. Fluent, pleasing speech. Not this cobbled-together grunting of yours.”

“What Mijaki?”

“What is Mijaki. It is the tongue of our people. We are Mijaki. This land is Mijak, gift of the god.” When she looked at him, not understanding, he shook his head. “He never taught you that much, your father?”

Father. He meant the man? She shrugged. “She-brats like goats. Who want teach goats?”

“Only godforsaken fools,” muttered Yagji.

Abajai shot him a dark look. “What of your mother?”

She sniggered. “Woman not teach. Man beat woman if she talk she-brats.” She sipped from the cup carefully, not sadsa this time, but tea. It was cool enough to drink. She gulped, suddenly thirsty. “Woman try. Talk a little, when man gone.”

“Did anybody else talk to you?”

“Sometimes.” She shrugged. “Man not like. But Hekat listen to man. To man’s boys. To men visit man. Hekat learn words. Learn counting.”

Abajai smiled. “Clever Hekat.” He lifted the jug again. “Honey is sweet. You know sweet?”

She shook her head, staring as Abajai poured a sticky gold stream onto her corncakes. “Eat,” he said, still smiling. “Use your fingers.”

“I thought you wanted it civilized,” protested Yagji.

“That will come,” said Abajai, as she put down the cup and balanced the plate more firmly in her lap. “For now let her touch the world with her fingers. Let it become real. Something to be embraced, not feared. If she is to make my fortune, she—”

“Our fortune,” said Yagji, and pointed at her plate. “You heard Aba, monkey. Eat! If you don’t eat there’ll be no meat on your bones and the good coin we paid for you will have been wasted!”

More goat words from Yagji. She would listen to Abajai. She folded a corncake in half and shoved it into her mouth. Her eyes popped as the sticky gold honey melted on her tongue. This was sweet? This—this—

Abajai and Yagji were laughing at her. “So? You like honey, Hekat?” said Abajai.

She chewed. Swallowed. Looked down at the other honey-soaked corncakes. Cold now, but she didn’t care about that. “Hekat like.”

“You should say thank you,” said Yagji, sniffing. “Only savages and monkeys have no manners. Say: Thank you, Yagji and Abajai.”

Her tongue yearned for more sweet. “Thank you, Abajai and Yagji.” She smiled, for Abajai alone. “Thank you for honey.”

Abajai patted her cheek. “You are welcome, Hekat. Now eat. The sun flies up. We must go.”

As she obeyed his word, stuffing sweet corncakes into her mouth, Yagji took the honey jar from Abajai and poured it over his own food. “Educate it if you must, Aba, but do refrain from fondling. As slaves go it might be quick-witted but your pet does not understand as much as you think.”

Abajai laughed, and drank his tea.

After breakfast they climbed onto the white camels and the caravan continued, traveling slowly but steadily beneath the hot blue sky. Every highsun Abajai taught Hekat proper Mijaki speech, and Yagji grumbled. Soon after newsun on the sixteenth day the land changed from flat to uneven, with ravines and steep hillsides. Four fingers after the nineteenth highsun they reached a road that twisted and turned like a snake, then plunged downward over a sharp jutting edge. Tall spindly trees with whippy branches crowded close on either side, flogging their faces and arms and legs. The camels complained with every step, and Abajai tightened his arm around Hekat’s middle, leaning back, as they shuffled to the bottom.

She gasped when they reached it. Here was green land spread before them! Thick grass wherever she looked, and more flowering bushes than ever grew in the village. Springs of water, bursting from underground. Aieee! She wished they could stop, she wanted to touch the bubbling water, to run with bare feet in all the growing grass, but lowsun was casting its long thin shadows. They would have to camp soon. Yagji was asleep already, trusting his camel to keep pace with Abajai.

Abajai woke him. “We have reached the lands of Jokriel warlord, Yagji. The savage north is left behind.”

Grunting, snuffling, Yagji straightened from his sleeping slouch. “At last. I never wish to travel there again, Aba. Make a note.”

“We travel where the god desires,” said Abajai. “Now let us do our duty to the godpost, then seek a pleasant place to camp.”

There was a godpost, Hekat saw, a little further along the road. Tall and grim and scorpion-carved, with a white stone crow at its top. No godbowl for offerings at its base, but a craggy lump of blue crystal. Abajai and Yagji halted their camels and the slave train, and Hekat watched as Abajai went to the godpost, took two small carved cylinders from his robe’s pocket and pressed them to the unremarkable stone. Bright light flared, brief as a falling star. Surprised, she looked at Yagji.

“The warlord guards the borders of his lands,” said Yagji. “Traders travel wherever they please, but still we must announce our presence and prove we have paid our road-right taxes.”

She did not know what a warlord was, or understand what Yagji meant or how Abajai had made the light flare from the stone.

“Tchut tchut,” Yagji said, impatient with her not knowing. “Let Aba explain if he wishes. I couldn’t care less what you know and what you do not.”

But Abajai wasn’t interested in talking of stones and warlords when he returned to his camel. He only cared for making camp. As they rode on, looking for the best place to spend the night, she saw small grey animals with long ears in the grass on either side of them. Abajai gave his word and Obid killed the bounding creatures with a slingshot. Every time he stuffed a limp body into the sack slung over his shoulder he flashed Abajai a broad smile.

“Rabbits,” said Abajai, seeing her confusion. “You do not know rabbits?”

She shook her head. “No rabbits village.”

“You are far from your village now, Hekat. Forget that place, it does not exist.”

She nodded. “Yes, Abajai. How far Todorok village?”

“We will reach it a finger or two past highsun tomorrow.”

“More honey there?” she asked him hopefully.

That made him laugh. “Perhaps. Slaves, too.”

She felt a moment’s prickling. If he found a she-brat more precious than her . . . “Many slaves now.”

“There is no such thing as too many slaves, Hekat.”

They should talk of something else. She frowned, and carefully put her words together in the way he told her she must. “How far is Et-Raklion?”

He made a pleased sound in his throat. “Many godmoons caravanning still. Your village lies at the doorstep of The Anvil, Hekat. The Anvil. You know it?”

She nodded. The Anvil was the fierce forever desert one highsun’s ride from the village godpost. She’d never seen it, of course, but knew of men and boys lured into it hunting sandcats, who were never seen again. She used to wish the man would be so foolish.

“Et-Raklion sits at the far side of Mijak. Et-Raklion city, where the warlord lives, where we live, lies close to the Mijaki border, half a godmoon’s swift travel from the Sand River.”

Bewildered, she wriggled around to look at him. “Border? Sand River?”

He shook his head. “Your world would fit in a stunted nutshell. Hekat. The border is where Mijak ends. The Sand River is a desert, like The Anvil, though not as vast. You understand?”

Beside them, Yagji roused. “Save your breath, Aba. It doesn’t need geography. Teach it a dozen ways to spread its legs and it’ll know more than enough for our purpose.”

She struggled to untangle his meaning. “Mijak ends?”

“Yes.” Abajai rested his warm hand on the back of her neck. “At the Sand River. Beyond the Sand River lie other lands. We do not go to those places, the people there are dead to us.”

“Why?”

Abajai shrugged. “Because the god has said it.”

“Why?”

Yagji squealed and kissed his lizard-foot amulet. Abajai’s fingers closed around her neck, painted nails biting her throat, and his lips touched her ear. “You wish to live, Hekat?”

Heart pounding, she nodded. Abajai’s voice had turned dark and cold. He was angry. What had she done? His harsh breath scoured her cheek.

“Never ask the god why. Not in your heart and never with your mouth. You understand?”

No, but he was hurting her. Again, she nodded.

“Good,” he said, and let her go. “That is all you learn today.”

Yagji had kissed his amulet so hard the carved yellow stone had split his flesh. A thin thread of blood dribbled down his chin. He touched the small wound, stared at the blood, then leaned over to thrust his wet red finger into Abajai’s face.

“See this, Aba! The god bites me! It gives a sign! Dream no more of fortune. Sell your precious Hekat in Todorok, I beg you!”

Abajai gave him a square of white cloth. “The god does not punish sideways, Yagji. You bleed for your own sin, or by accident. Hekat is not for sale in Todorok.”

Hekat let out a deep breath and waited for her heart to slow. She didn’t want Abajai to know she’d been so frightened. For a long time Yagji rode in silence, the white cloth held to his cut lip with trembling fingers. His eyes were wide and staring far ahead, into the gathering dusk.

“We’ll talk on this again, Abajai,” he said at last, very softly. “Before we reach Et-Raklion.”

“We’ll talk of many things, Yagji,” said Abajai, as softly. “Before we reach Et-Raklion.”

CHAPTER THREE

They reached Todorok village a half-finger after highsun next. Hekat stared and stared, so much strangeness to see.

First was Todorok’s godpost. It looked new, untouched by harsh sunshine, unsplintered by windstorms. Twice as tall as the godpost she’d left behind in the village, it was painted bright godcolors: purple and green and gold. Scorpions carved from shiny black crystal crawled around and around to the white crow at its top, carrying messages to the god. The god-bowl at its base was a scorpion too, heavy black iron, tail raised, claws outstretched, and its belly was full of coin. Abajai dropped gold into it as they passed and pressed his knuckles to his breast in respect. So did Yagji show respect. So did she, after Abajai pinched her shoulder and growled.

Barely had she stopped marveling over the godpost than her breath was stolen a second time. Todorok village was big. It had wide streets covered in smooth stones and houses painted white. Their roofs weren’t made of grass, they had scales, like a snake, many different colors. The air was clean, it did not stink of goats and men.

The villagers waving as the caravan passed wore bright clothes all over and coverings on their heads. Strange. They had flesh on their bones. Their skin was shiny and smooth, not baked into cracked leather by endless sun. Some of them were she-brats, not chained in secret but walking freely beneath the sky, no man close to poke and strike.

How could that be?

Abajai and Yagji led the caravan to the center of the village, where the road opened into a large square. White buildings lined every side. One was a godhouse, its door and windows bordered with stinging scorpions and striking snakes. Here were scattered clumps of colorful flowers and water bubbling inside a ring of white rocks to splash unused on the ground.

Hekat couldn’t believe it. If she had ever once wasted so much the man would not have waited for the godspeaker, he would have broken her body himself and tossed it to his dogs.

The villagers gathered to greet them, smiled and laughed, they were pleased to see the Trader caravan. A smiling godspeaker stepped forward as Abajai and Yagji halted their camels. Not stooped and skinny, this one. His arms weren’t stringy, his robes were clean. The scorpion-shell bound to his forehead was uncracked and shiny. He had all his teeth and fingers.

“Welcome, Trader Abajai, Trader Yagji,” said the godspeaker. “It is many seasons since you were seen in Todorok.”

Abajai ordered his camel to kneel, climbed down, and snapped his fingers. Hekat climbed down after him and stood a little to one side, silent and wide-eyed. As Yagji’s camel folded its legs so the fat Trader might stand on the ground, Abajai said, “The god sends us where and when it desires, Toolu godspeaker. This far north good slaves grow thin on the ground, like grain without nourishment. But we are here this highsun, to trade for supplies and buy such flesh from you as promises us profit. If you have flesh to sell?”

“I am certain there will be some,” said the godspeaker. “Let us wait in the godhouse as word is sent to bring merchandise for your inspection. I will make sacrifice for your arrival.”

Abajai bowed. “The god sees you, godspeaker. And as we wait . . .” He took Hekat’s arm, tugging her forward. “You see this one?”

The godspeaker nodded, his curiosity almost hidden. “I see that one, Trader Abajai.”

“I wish it bathed and fed and dressed in cotton, with shoes upon its feet and charm-beads in its godbraided hair, for health and beauty and obedience. You will please me and the god to grant my desire. I will make an offering in return.”

The godspeaker’s hooded gaze lingered on Abajai’s scarlet scorpion, quiet in his cheek. Then he raised a sharp hand, so the snake-bones bangled round his wrist chattered. “Bisla.”

A short plump woman stepped forward from the watching crowd. Ivory amulets dangled from her ears and her nakedness was hidden beneath robes too fine for any female, surely. “Godspeaker.”

“Abajai wishes this one bathed and fed and dressed in cotton, with shoes upon its feet and charm-beads for health and beauty and obedience in its godbraided hair,” the godspeaker said, not looking at the woman. “You and your sisters may honor him so.”

“Yes, godspeaker.” The woman held out her hand. “Come, child.”

Hekat looked up at Abajai. “Go with her,” he said. “Obey her wishes but hold your tongue. There is nothing to fear, you will return to me before we leave.”

“Yes, Abajai,” she said, trusting him. His word was his word, he kept her safe.

The woman and two others took her to a white house two streets away from Abajai. Its lizard roof had scales of blue and yellow. Inside, the floor was made of wood—did so many trees grow anywhere, to be cut down and turned into houses?—and on top of the wood were large squares of colored wool, soft beneath her feet. The women hurried her to a room with no windows. Sunk into its floor was a deep round hole maybe six man-paces across, lined with smooth stones. Stone steps led down into it. The woman Bisla rang a bell. A moment later a large slave appeared at the door. He was bare-chested, sewn with beads across his breast. He wore loose green trousers and red cloth shoes with pointy toes.

“Mistress,” he said, his hairless head bowed.

“Hot water,” said the woman Bisla. “Fresh soap. Cloths. Brushes and combs. My bead box. My hand mirror. Tunic and pantaloons from Dily’s room, cotton, not linen or wool. And shoes.”

“Mistress,” the slave said again, and withdrew.

A wide wooden bench ran the length of one wall. The woman Bisla and her sisters pushed Hekat onto it. Then they stripped off the yellow robe Abajai had given her. Hekat would have shouted and snatched it back again, slapped the women for daring to touch Abajai’s gift. But Abajai had told her his word so she just pinched her lips and let them take it.

“Skinny! Skinny!” the woman Bisla exclaimed, pointing at her ribs. “Does Abajai not feed you, child?”

Abajai had told her not to talk. She shrugged.

“Is that yes or no?”

Another shrug.

“She’s afraid, poor thing,” said one of the other women. “I wonder who she is? Not Abajai’s get!” She arched her thin eyebrows at the others and giggled.

As slaves led by the hairless beaded man entered the room bearing leather buckets of steaming water, the woman Bisla frowned and shook her head. “Tcha! It is not needful to know these things.”

The hairless beaded slave put down the items the woman Bisla had ordered him to bring, then watched as one by one the other slaves emptied their buckets into the stone-lined hole. They left and returned many times until the hole was filled almost to the top. They placed four full wooden buckets to one side, bowed, and withdrew. The woman Bisla spread a large cloth beside the hole and on it placed a brush, a comb, a pile of smaller cloths and a pale pink jar. She took off its lid. Inside was something soft and slippery, smelling like flowers.

Amazed, Hekat stared at the hole full of water. Stared even more amazed as the woman Bisla stripped off her clothes and trod down the stone steps into it. The water reached up to her waist. Bisla held out her hand. “Come, child. Into the bath.”

She shook her head. It was a stoning sin to put your b. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...