- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

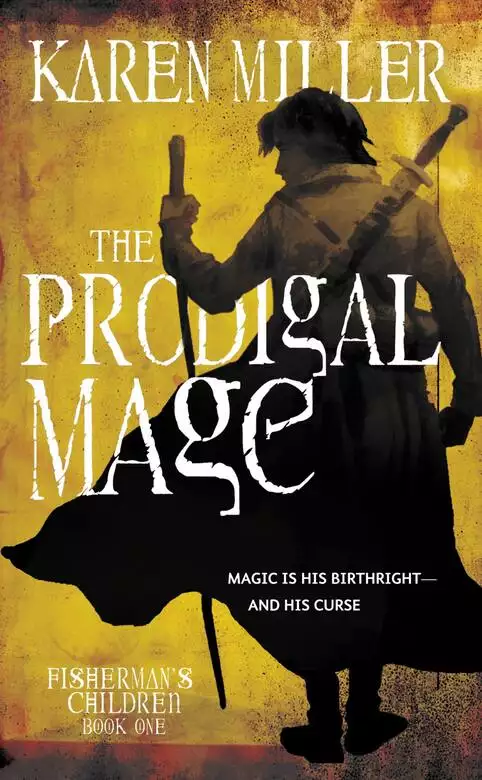

Synopsis

Many years have passed since the last great Mage War. It has been a time of great change. But not all changes are for the best, and Asher's world is in peril once more.

The weather magic that holds Lur safe is failing, and the earth feels broken to those with the power to see. Among Lur's sorcerers, only Asher has the skill to mend the antique weather map that governs the seasons, keeping the land from being crushed by natural forces. Yet, when Asher risks his life to meddle with these dangerous magics, the crisis is merely delayed, not averted.

Asher's son Rafel has inherited the father's talents, but has been forbidden to use them. Many died in the last Mage War and these abilities aren't to be loosed lightly into the world. But when Asher's last desperate attempt to repair the damage leaves him on his deathbed, Rafel's powers may not be denied. For his countrymen are facing famine, devastation, and a rift in the very fabric of their land.

Release date: July 23, 2009

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 512

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Prodigal Mage

Karen Miller

said no, Meister Tollin’s expedition didn’t need any little boys to help them, he cried… but not for long, because he had

a new pony, Dancer, and Mama had promised to come watch him ride. And then, ages and ages later, the expedition came back—which

was a surprise to everyone, since it was declared lost—and he was glad he hadn’t gone with Meister Tollin and the others because

while they were away exploring, four of the seven men sickened and died, wracked and gruesome for no good reason anyone could

see. Not even Da, and Da knew everything.

Once all the fuss was died down, some folk cheering and some weeping, on account of the men who got buried so far away, Meister

Tollin came to tell Da what had gone on while they were over Barl’s Mountains. They met in the big ole palace where all the

grown-up government things happened, where the royal family used to live once, back in the days when there was a royal family.

He knew all about them grand folk, ’cause Darran liked to tell stories. Da said Darran was a silly ole fart, and that was

mostly true. He was old as old now, with an old man’s musty, fusty smell. His hair was grown all silver and thin, and his

eyes were nearly lost in spiderweb wrinkles. But that didn’t matter, ’cause the stories he told about Lur’s royal family were

good ones. There was Prince Gar, Da’s best friend from back then. Darran talked about him the most, and blew his nose a lot

afterwards. There was the rest of the royal family: clever Princess Fane and beautiful Queen Dana and brave King Borne. It

was sad how they died, tumbling over Salbert’s Eyrie. Darran cried about that too, every time he remembered… but it didn’t

stop him telling the stories.

“You’re young to hear these tales, Rafel, but I won’t live forever,” he’d say, his face fierce and his voice wobbly. “And I can’t trust your father to tell you. He has… funny notions, the rapscallion. But you must know, my boy. It’s your birthright.”

He didn’t really understand about that. All he knew was he liked Darren’s stories so he never breathed a word about ’em in

case Da fratched the ole man on it and the stories went away.

He especially liked the one about Da saving the prince from being drownded at the Sea Harvest Festival in Westwailing. That

was a good story. Almost as good as hearing how Da saved Lur from the evil sorcerer Morg. But Darran didn’t tell him that one very often,

and when he did he always said not to talk about it after. He didn’t cry, neither, after telling it. He just went awful quiet.

Somehow that was worse than tears.

When he overheard Da telling Mama about Meister Tollin coming to see him, in the voice that said he was worrited and cross,

Rafel knew if he didn’t do a sneak he’d never find out what was going on—and he hated not knowing. The trouble with parents was they never thought you were old enough to know things. They praised you for being

a clever boy then they told you to run away and play, don’t bother your head about grown-up business.

He got so cross when they said things like that he had to hide in his secret place and crack stones with his magic, even though

Da would wallop him if he found out.

Of course he knew perfectly well he wasn’t supposed to do a sneak. He wasn’t supposed to do any kind of magic, not just stone-cracking, not unless Da or Mama was with him. Or Meister Rumly, his tutor. Da and Mama said

it was dangerous. They said because he was special, a prodigy, he had to be very careful or someone might get hurt. He thought they were boring and silly, all that fussing, but he did

as he was told. Mostly. Except sometimes, when he couldn’t hold the magic in any more, when it skritched him so hard he wanted

to shout, he danced leaves without the wind or made funny water shapes in his bath. Only playing. There was no harm in that.

The time when Da said he and Meister Tollin were going to meet and talk about the failed expedition, that was when he was

s’posed to be in his lessons. But the moment Meister Rumly left him to work some problems on his own, and took himself off

for a chinwag with Darran, he did the kind of earth magic that helped Mama creep up on a wild rabbit she wanted for supper

and fizzled away to the white stone palace. He had to wait until there weren’t any comings and goings through its big double

doors before he could hide in the tickly yellow lampha bushes beside the front steps. Waiting was hard. He kept thinking Meister

Rumly would find him. But Meister Rumly didn’t come, and nobody saw him scuttle into the bushes.

Da and Meister Tollin came along a little while after, and he held his breath in case they didn’t choose to talk in the palace’s

ground floor meeting room where Da and the Mage Council made important decisions for Lur.

But they did, so once they were safely inside he crawled on his hands and knees between the lampha and the palace wall until

he fetched up right under that meeting room window.

There, hunkered down on the damp earth, yellow lampha blossom tickling his nose so he had to keep rubbing it on his sleeve

in case he sneezed, and got caught, and landed himself into wallopin’ trouble, he listened to what Meister Tollin had to tell

Da about his adventure, that Da didn’t want anybody else to hear.

The lands beyond the Wall were dark and grim, Meister Tollin said. Weren’t nothing green or growing there. No people, neither.

All they’d found was cold death and old decay. Mouldy bones and abandoned houses, falling to bits. There wasn’t even a bird

singing in the stunted, twisted trees. That sorcerer Morg had killed everything, Meister Tollin said. Might be Lur was the

only living place left in the whole world. It felt like it. On the other side of Barl’s Mountains it felt like they were all

alone, in the biggest graveyard a man would ever see.

Meister Tollin’s voice sounded funny saying that, wobbly and hoarse and sad. Rafel felt his eyes go prickly, hearing it. All alone in the world. Meister Tollin was using tricky words but he understood what they meant. Most every day Mama told him he was too smart for

his own good, but he didn’t mind that kind of scolding because in her dark brown eyes there was always a smile.

Next, Da wanted to know why Meister Tollin and the others had broken their promise and not contacted the General Council through

the circle stones they took with them. They couldn’t, said Meister Tollin, sounding cross. In the dead lands beyond Barl’s

Mountains their magic wouldn’t work. Not gentle Olken magic, not pushy Doranen magic. They tried and they tried, but they

had to do everything the hard way. Just by themselves, no magic to help out.

Rafel felt himself shiver cold. No Olken magic, the way it was before Da saved Lur? That was nasty. He didn’t want to think

on that.

Then Da wanted to know more about what happened to the four men who died. Three were Olken, and two of them were his friends,

Titch and Derik. They’d been Circle Olken, and helped him in the fight against Morg. Da sounded sad like Darran, saying their

names. It was horrible, hearing Da sad. Scrunched so small under the meeting room’s open window, Rafel tried to think how

he’d feel if his best friend Goose died. That made his eyes prickle again even harder.

But before he could hear what Meister Tollin had to say about those men getting sick for no reason, Meister Rumly came calling

to see where he was. His manky ole tutor had a sneaky Doranen seekem crystal that Olken magic couldn’t fool. Meister Rumly

was allowed to use it to find him. Da had said so.

It wasn’t fair. There were rules about that for everyone else, about using Doranen magic on folk. There were rules for pretty much everything to do with magic and big trouble if people broke them—but sometimes they did and then Da had to go down to Justice Hall and

wallop ’em the way grownups got walloped. He hated doing that. Speaking on magic at Justice Hall got Da so riled only Mama

could calm him down.

Remembering his father’s fearsome temper, Rafel crawled his way out of the lampha bushes and scuttled to somewhere Meister

Rumly could find him and not cause a ruckus. If there was a ruckus Da would come out to see why and his tutor would tell tales.

Then Da would ask what he’d been up to and he’d say the truth. He’d have to, because it was Da. And he didn’t want that, because

when Da said “Rafel, you be a little perisher too smart for his own good” he hardly ever smiled. Not with his face and not in his eyes.

So he took himself off to the Tower stables and let Meister Rumly find him hobnobbing with his pony. Knowing full well he’d

been led on a wild goose-chase, his tutor wittered on and on as they returned to lessons in the Tower. And all the long afternoon,

bored and restless, he wondered and he wondered what else Tollin told Da.

That night at supper, sitting at the table in the fat round solar where they ate their meals, his parents talked a bit about

Meister Tollin’s expedition. They didn’t mention any of the scary parts, because his stinky baby sister was there, banging

her spoon on her plate and making stupid sounds instead of saying real words like Uncle Pellen’s little girl could. He wished

Da and Mama would send Deenie away so they could all talk properly.

“So that’s that,” said Da, who’d called Meister Tollin a fool for going, and the others too, even though Titch and Derik were

his friends. “It’s over. And there’ll be no more expeditions, I reckon.”

“Really?” said Mama, her eyebrows raised in that way she had. “Because you know what people are like, Asher. Let enough time

go by and—”

Da slurped down some spicy fish soup. “Fixed that, didn’t I?” he growled. “Tollin’s writin’ down an account of what happened.

Every last sinkin’ thing, nowt polite about it. I’ll see it copied and put where it won’t get lost, and any fool as says we

ought to send more folk over Barl’s Mountains then Tollin’s tale will remind ’em why that ain’t a good idea.”

Mama made the sound that said she wasn’t sure about that, but Da paid no attention.

“Any road, ain’t no reason for the General Council to give the nod for another expedition,” he said. “Tollin made it plain—there

ain’t nowt to find over the mountains.”

“Not close to Lur perhaps,” said Mama. “But Tollin didn’t get terribly far, Asher. He was only gone two months, and most of

that time was spent dealing with one disaster after another.”

“He got far enough,” Da said, shaking his head. “Morg poisoned everything he touched, Dath. Ain’t nowt but foolishness to

think otherwise, or to waste time frettin’ on what’s so far away.”

“Oh, Asher,” Mama said, smiling. Da’s grouching nearly always made her smile. “After six hundred years locked up behind those

mountains, you can’t blame people for being curious.”

Six hundred years. Rafel could hardly imagine it. That was about a hundred times as long as he’d been alive. Mama was right. Of course people

wanted to know. He wanted to know. He was as miserable as she was that Meister Tollin and the others hadn’t found anything good on the other

side of Barl’s Mountains.

But Da wasn’t. He gave Mama a look, then soaked his last bit of bread in his soup. “Reckon I can blame ’em, y’know,” he grumbled

around a full mouth. That wasn’t good manners, but Da didn’t care. He just laughed when Mama said so and was ruder than before.

“You tell me, Dath, what’s curiosity ever done but black the eye of the fool who ain’t content to stay put?”

Rafel saw his mother cast him a cautious glance, and made his face look all not caring, as though he really was a silly little

boy who didn’t understand. “Tollin and the others were only trying to help,” she murmured. “And I’m sorry things went wrong.

I wanted to meet the people who live on the other side of the mountains. I wanted to hear their stories. And now we find there

aren’t any? I think it’s a great pity.”

With a grunt Da reached for the heel of fresh-baked bread on its board in the centre of the table. Tearing off another hunk

of it, he glowered at Mama. Not angry at her, just angry at the world like he got sometimes. Da was never angry with Mama.

“I tell you, Dathne,” he said, waving the bread at her, “here’s the truth without scales on, proven by Tolin—there ain’t no

good to come of sniffin’ over them mountains. What price have we paid already, eh? Titch and Derik dead, it be a cryin’ shame.

Pik Mobley too, that stubborn ole fish. And that hoity-toity Lord Bram. Reckon a Doranen mage should’ve bloody known better,

but he were a giddy fool like the rest of ’em. They should’ve listened to me. Ain’t I the one who told ’em not to go? Ain’t

I the one told ’em only a fool pokes a stick in a shark’s eye? I am. But they wouldn’t listen. Both bloody Councils, they

wouldn’t listen neither. And all we’ve got to show for it is folk weepin’ in the streets.”

Sighing, Mama put her hand on Da’s arm. “I know. But let’s talk about it later. Supper will go cold if we go on about it now.”

“There ain’t nowt to talk on, Dath,” said Da, tossing his bread in his empty bowl and shoving it away. “What’s done is done.

Can’t snap m’fingers and bring ’em all back in one piece, can I?”

Da was so riled now he sounded like the cousins from down on the coast, instead of almost a regular City Olken. He sounded

like the sky looked with a storm blowing up. Even though stinky Deenie was a baby, three years old and still piddling in her

nappies, she knew about that. She threw her spoon onto the table and started wailing.

“There now, Asher!” said Mama in her scolding voice. “Look what you’ve done.”

Rafel rolled his eyes as his mother started fussing with his bratty sister. Scowling, Da pulled his bowl back and spooned

up what was left of his soup and soggy bread, muttering under his breath. Rafel kept his head down and finished his soup too,

because Da didn’t like to see good food wasted. When his bowl was empty he looked at his father, feeling his bottom lip poke

out. He had a question, and he knew it’d tickle him and tickle him until he had an answer.

“Da? Can I ask you something?”

Da looked up from brooding into his soup bowl. “Aye, sprat. Y’know you can.”

He felt Mama’s eyes on him, even though she was spooning mashed-up sweet pickles into the baby. “Da, don’t you want anyone

going over the mountains? Not ever?”

“No,” said Da, and shook his head hard. “Ain’t no point, Rafe. Everythin’ we could ever want or need, we got right here in

Lur.” He looked at Mama, smiling a little bit, with his eyes all warm ’cause he loved her so much. Da riled fast, but he cooled

down fast too. “We got family and friends and food for the table. What else do we need, that we got to risk ourselves over

them mountains to find?”

Rafel put down his spoon. Da was a hero, everyone said so. Darran wasn’t the only one who told him stories. Da hated to hear

folk say it, his face went scowly enough to bust glass, but it was true. Da was a hero and he knew everything about everything…

But I don’t believe him. Not about this.

Oh, it was an awful thing to think. But it was true. Da was wrong. There was something to find beyond the mountains, he knew it—and one day, he’d go. He’d find out what was there.

Then I’ll be a hero too. I’ll be Rafe the Bold, the great Olken explorer. I’ll do something special for Lur, just like my

da.

It was a trivial dispute… but that wasn’t the point. The point, as he grew tired of saying, was that dragging a Doranen into Justice Hall, forcing him to defend his use of magic, was demeaning.

It was an insult. Placing any Olken hedge-meddler on level footing with a Doranen mage was an insult. And that included the vaunted Asher

of Restharven. His mongrel abilities were the greatest insult of all.

“Father…”

Rodyn Garrick looked down at his son. “What?”

Kept out of the schoolroom for this, the most important education a young Doranen could receive, Arlin wriggled on the bench

beside him. And that was another insult. In Borne’s day a Doranen councilor was afforded a place of respect in one of Justice Hall’s gallery seats—but not

any more. These days the gallery seats remained empty and even the most important Doranen of Lur were forced to bruise their

bones on hard wooden pews, thrown amongst the general population.

“Arlin, what?” he said. “The hearing’s about to begin. And I’ve told you I’ll not tolerate disruption.”

“It doesn’t matter,” Arlin whispered. “I’ll ask later.”

Rodyn stifled his temper. The boy was impossible. His mother’s fault, that. One son and she’d coddled him beyond all bearing.

A good thing she’d died, really. Undoing ten years of her damage was battle enough.

Justice Hall buzzed with the sound of muted conversations, its cool air heavy with a not-so-muted sense of anticipation. Not

on his part, though. He felt only fury and dread. He’d chosen to sit himself and his son at the rear of the Hall, where they’d

be least likely noticed. Aside from Ain Freidin, against whom these insulting and spurious charges were laid, and her family,

he and Arlin were the only Doranen present. Well, aside from his fellow councilor Sarnia Marnagh, of course. Justice Hall’s

chief administrator and her Olken assistant conferred quietly over their parchments and papers, not once looking up.

Everyone was waiting for Asher.

When at last Lur’s so-called saviour deigned to put in an appearance, he entered through one of the doors in the Hall’s rear

wall instead of the way entrances had been made in Borne’s day: slowly and with grave splendour descending from on high. So

much for the majesty of law. Even Asher’s attire lacked the appropriate richness—plain cotton and wool, with a dowdy bronze-brown

brocade weskit. This was Justice Hall. Perhaps Council meetings did not require velvet and jewels, but surely this hallowed

place did.

It was yet one more example of Olken contempt.

Even more irksome was Sarnia Marnagh’s deferential nod to him, as though the Olken were somehow greater than she. How could

the woman continue to work here? Continue undermining her own people’s standing? Greater? Asher and his Olken brethren weren’t even equal.

Arlin’s breath caught. “Father?”

With a conscious effort Rodyn relaxed his clenched fists. This remade Lur was a fishbone stuck in his gullet, pinching and

chafing and ruining all appetite—but he would serve no-one, save nothing, if he did not keep himself temperate. He was here

today to bear witness, nothing more. There was nothing more he could do. The times were yet green. But when they were ripe…

oh, when they were ripe…

I’ll see a harvest gathered that’s long overdue.

At the far end of the Hall, seated at the judicial table upon its imposing dais, Asher struck the ancient summons bell three

times with its small hammer. The airy chamber fell silent.

“Right, then,” he said, lounging negligent in his carved and padded chair. “What’s all this about? You’re the one complaining,

Meister Tarne, so best you flap your lips first.”

So that was the Olken’s name, was it? He’d never bothered to enquire. Who the man was didn’t matter. All that mattered was

his decision to interfere with Doranen magic. Even now he found it hard to believe this could be happening. It was an affront

to nature, to the proper order of things, that any Olken was in a position to challenge the rights of a Doranen.

The Olken stood, then stepped out to the speaker’s square before the dais. Bloated with too much food and self-importance,

he cast a triumphant look at Ain Freidin then thrust his thumbs beneath his straining braces and rocked on his heels.

“Meister Tarne it is, sir. And I’m here to see you settle this matter with my neighbour. I’m not one to go looking for unpleasantness.

I’m a man who likes to live and let live. But I won’t be bullied, sir, and I won’t be told to keep my place. Those days are

done with. I know my place. I know my rights.”

Asher scratched his nose. “Maybe you do, but that ain’t what I asked.”

“My apologies,” said the Olken, stiff with outrage. “I was only setting the scene, sir. Giving you an idea of—”

“What you be giving me, Meister Tarne, is piles,” said Asher. “Happens I ain’t in the mood to be sitting here all day on a

sore arse, so just you bide a moment while I see if you can write a complaint better than you speak one.”

As the Olken oaf sucked air between his teeth, affronted, Asher took the paper Sarnia Marnagh’s Olken assistant handed him.

Started to read it, ignoring Tarne and the scattered whispering from the Olken who’d come to point and stare and sneer at

their betters. Ignoring Ain Freidin too. Sarnia Marnagh sat passively, her only contribution to these proceedings the incant

recording this travesty of justice. What a treacherous woman she was. What a sad disappointment.

Condemned to idleness, Rodyn folded his arms. It seemed Asher was in one of his moods. And what did that bode? Since Barl’s

Wall was destroyed this was the twelfth—no, the thirteenth—time he’d been called to rule on matters magical in Justice Hall.

Five decisions had gone the way of the Doranen. The rest had been settled in an Olken’s favour. Did that argue bias? Perhaps.

But—to his great shame—Rodyn couldn’t say for certain. He’d not attended any of those previous rulings. Only in the last year

had he finally, finally, woken from his torpor to face a truth he’d been trying so hard—and too long—to deny.

Lur was no longer a satisfactory place to be Doranen.

“So,” said Asher, handing back the written complaint. “Meister Tarne. You reckon your neighbour—Lady Freidin, there—be ruining

your potato crop with her magework. Or did I read your complaint wrong?”

“No,” said the Olken. “That’s what she’s doing. And I’ve asked her to stop it but she won’t.” He glared at Ain Freidin. “So

I’ve come here for you to tell her these aren’t the old days. I’ve come for you to tell her to leave off with her muddling.

Olken magic’s as good as hers, by law, and by law she can’t interfere with me and mine.”

Arlin, up till now obediently quiet, made a little scoffing sound in his throat. Not entirely displeased, Rodyn pinched the

boy’s knee in warning.

“How ezackly is Lady Freidin spoiling your spuds, Meister Tarne?” said Asher, negligently slouching again. “And have you got

any proof of it?”

Another hissing gasp. “Is my word not enough?” the potato farmer demanded. “I’m an Olken. You’re an Olken. Surely—”

Sighing, Asher shook his head. “Not in Justice Hall, I ain’t. In Justice Hall I be a pair of eyes and a pair of ears and I

don’t get to take sides, Meister Tarne.”

“There are sworn statements,” the chastised Olken muttered. “You have them before you.”

“Aye, I read ’em,” said Asher. “Your wife and your sons sing the same tune, Meister Tarne. But that ain’t proof.”

“Sir, why are you so quick to disbelieve me?” said the Olken. “I’m no idle troublemaker! It’s an expense, coming here. An

expense I can’t easily bear, but I’m bearing it because I’m on the right side of this dispute. I’ve lost two crops to Lady

Freidin’s selfishness and spite. And since she won’t admit her fault and mend her ways, what choice do I have but to lay the

matter before you?”

Asher frowned at the man’s tone. “Never said you weren’t within your rights, Meister Tarne. Law’s plain on that. You are.”

“I know full well I’m not counted the strongest in earth magic,” said the Olken, still defiant. “I’m the first to admit it.

But I do well enough. Now I’ve twice got good potatoes rotted to slime in the ground and the market price of them lost. That’s

my proof. And how do I feed and clothe my family when my purse is half empty thanks to her?”

The watching Olken stirred and muttered their support. Displeased, Asher raised a hand. “You lot keep your traps shut or go

home. I don’t much care which. But if you don’t keep your traps shut I’ll take the choice away from you, got that?”

Rodyn smiled. If he’d been wearing a dagger he could have stabbed the offended silence through its heart.

“Meister Tarne,” said Asher, his gaze still sharp. “I ain’t no farmer, but even I’ve heard of spud rot.”

“Well, sir, I am a farmer and I tell you plain, I’ve lost no crops to rot or any other natural pestilence,” said the Olken. “It’s Doranen

magic doing the mischief here.”

“So you keep sayin’,” said Asher. “But it don’t seem to me you got a shred of evidence.”

“Sir, there’s no other explanation! My farm marches beside Lady Freidin’s estate. She’s got outbuildings near the fence dividing

my potatoes from her fields. She spends a goodly time in those outbuildings, sir. What she does there I can’t tell you, not

from seeing it with my own eyes. But my ruined potato crops tell the story. There’s something unwholesome going on, and that’s

the plain truth of it.”

“Unwholesome?” said Asher, eyebrows raised, as the Olken onlookers risked banishment to whisper. “Now, there’s a word.”

Rodyn looked away from him, to Ain Freidin, but still all he could see was the back of her head. Silent and straight-spined,

she sat without giving even a hint of what she thought about these accusations. Or if they carried any merit. For himself…

he wasn’t sure. Ain Freidin was an acquaintance, nothing more. He wasn’t privy to her thoughts on the changes thrust so hard

upon their people, or what magic she got up to behind closed doors.

“Before it was a Doranen estate, the land next door to mine was a farm belonging to Eby Nye, and when it was a farm my potatoes

were the best in the district,” said the Olken, fists planted on his broad hips. “Not a speck of slime in the crop, season

after season. Two seasons ago Eby sold up and she moved in, and both seasons since, my crops are lost. You can’t tell me there’s

no binding those facts.” He pointed at Ain Freidin. “That woman’s up to no good. She’s—”

“That woman?” said Ain, leaping to her expensively shod feet. “You dare refer to me in such a manner? I am Lady Freidin to you, and to

any Olken.”

“You can sit down, Lady Freidin,” said Asher. “Don’t recall askin’ you to add your piece just yet.”

Young and headstrong, her patience apparently at an end, Ain Freidin was yet to learn the value of useful timing. She neither

sat nor restrained herself. “You expect me to ignore this clod’s disrespect?”

“Last time I looked there weren’t a law on the books as said Meister Tarne can’t call you that woman,” said Asher. “I’m tolerable sure there ain’t even a law as says he can’t call you a slumskumbledy wench if that be what takes his fancy. What I am tolerable sure of is in here, when I tell a body to sit down and shut up, they do it.”

“You dare say so?” said Ain Freidin, her golden hair bright in the Hall’s window-filtered sunlight and caged glimfire. “To me?”

“Aye, Lady Freidin, to you,” Asher retorted, all his Olken arrogance on bright display. “To you and to any fool as walks in

here thinkin’ they’ve got weight to throw a

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...