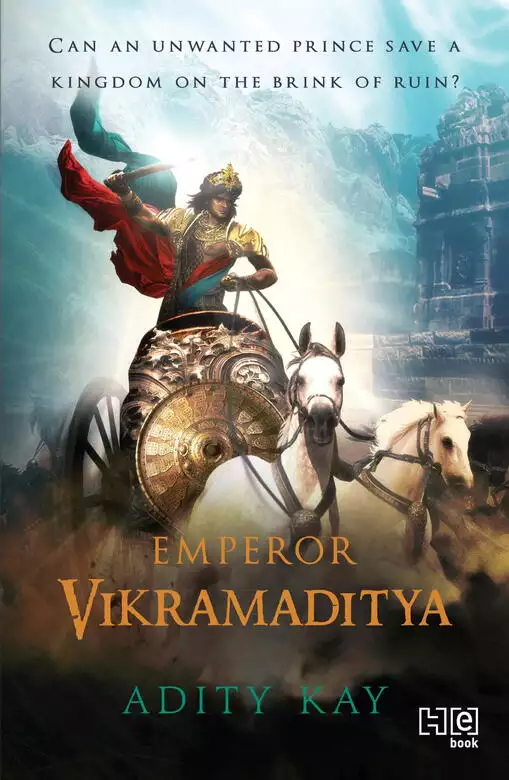

Emperor Vikramaditya

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Love. Family. Home. Chandra has sacrificed it all at the altar of duty. Now, he has to choose between duty and justice. India, fourth century CE. Peace reigns in the land of Magadha, under the rule of Emperor Samudragupta. New alliances are made every day, trade and the arts flourish, and Chandra – the young prince – leads his father’s horse across the length of Bharatvarsha as a part of the ashwamedha yagna, cementing the emperor’s influence. The kingdom is at its peak, but Chandra’s thoughts are clouded, his heart heavy. As his elder brother, Ramagupta, prepares to take their ageing father’s place on the throne, Chandra, bound as he is to obey the future king, wrestles constantly with his brother’s decisions – decisions he believes are inimical to the stability of the empire. And so begins a tale of conflict between two brothers: one drunk on power, buoyed by the unmitigated support of the Pataliputra court, the other a seeming outsider in the palace, who yet commands the people’s loyalty and love. And when an enemy unlike any before rises to challenge the Guptas’ might, Chandra must overcome his demons in order to protect his people and become a king in his own right – he must become Vikramaditya.

Release date: July 25, 2019

Publisher: Hachette India

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Emperor Vikramaditya

Adity Kay

As the time for the queen’s confinement drew near, the royal palace in Pataliputra wore a festive air. The conch shells blew every sunrise, and then again at sunset. The priests chanted sacred verses at the auspicious hours and cymbals clashed resoundingly.

Yet, the king, Samudragupta, looked worried, as he ran his fingers through his wispy beard. His upper garment had slipped off his right shoulder, making a battle scar visible but he barely noticed. The king’s worry was something only his closest advisers could read, for he hid it well. In all his conquests and campaigns to ensure Magadha was secure, he had looked confident, riding at the head of his armies. But now his advisers could see him pacing in his chambers late into the night, and sometimes even before the sun rose in the sky. Only they knew that it wasn’t just the delicate state of his queen, Dattadevi, that had him so worried.

‘I hope it isn’t a son,’ he told his minister, Harisena, who looked most uncomfortable. To him, such a statement was akin to blasphemy; the minister knew of no man who would not look forward to a son’s birth.

On seeing the expression on his minister’s face, Samudragupta laughed sadly. ‘I know how you feel, Harisena, but you know that I don’t mean to rake up the past.’

‘But it was all some time ago, my lord,’ Harisena said tentatively, exchanging a quick glance with Varahamihira, the king’s trusted guru and acharya. What the minister did not say was how inauspicious the king’s words sounded. Instead, Harisena followed the king’s gaze towards the courtyard and, for a moment, the worried lines on the minister’s forehead cleared.

The two of them watched as the young prince Ramagupta played with a toy chariot, pulling it with a string and shouting with delight every time the wheels ran aground over the wet mud. When the prince tripped and fell over the extended string that stretched from the chariot, they chuckled.

Finally, Harisena spoke, ‘My lord, I do not want to bring back bad memories. But, from the bad, much good has come. Magadha has a more capable ruler. The queen’s health has been restored; she is better looked after now. Magadha has an heir already and everything looks promising. You must not dwell on the past, especially when,’ Harisena touched his ears in reverence, ‘your father willed it so.’

The minister knew he was treading on dangerous ground, as this was a subject that Samudragupta had, for quite some time, forbidden. After all, it referred to the delicate matter of Samudragupta’s accession being contested by his stepbrother, Kacha, governor of the hill provinces, despite the fact that Chandragupta, had willed that his son, Samudragupta, succeed him.

‘True, my father did, but even then, there was violence,’ Samudragupta replied, sounding impatient. Then he hesitated, turning to his two oldest ministers, Harisena and Varahamihira. ‘You are right in thinking that I am worried. Sons fight despite their father’s wishes. Brothers fight each other to the death. This land I rule over? Its history shows that. It seems as though the weight of kingship is too much to bear, that those who become kings, who love the power, must pay a price. It has happened so often and it always ends in blood. I’d like the throne to be secure, to be peaceful. Magadha has seen too much blood spilled time and time again.’ He smiled wistfully. ‘That is why I wish for a daughter this time.’

Then, just as the bells from the palace temple began to chime, Samudragupta turned to Varahamihira and spoke once again, this time in a softer tone. ‘It is good you are here, acharya, away from your hermitage. What are your thoughts?’

These days, Varahamihira, frail and stooping with age, preferred to spend his time at his forest hermitage located in Lalitapatna, north-west of Pataliputra. Here, it was said, he shared knowledge and learnt much from the yogis and sages who came from across the mountains. His grey-green eyes had now misted over with age, and his once majestic beard was streaked with grey. Varahamihira was still venerated for his ability to foretell the future by studying the stars, yet this skill was secretly contested in certain circles within the palace, especially by those jealous of the king’s support of the sage. Harisena, younger than Varahamihira by a decade or so, had lost most of his hair. His well-oiled bald pate glistened as it caught the light of the tapers, and his gaze shifted often, darting around the room before moving back to the king. It seemed he looked for something, hoping to alleviate the tension in the chamber.

Varahamihira joined his hands in greeting. ‘Your glory will spread far, O king.’

The king inclined his head in acceptance of the acharya’s blessing but Varahamihira’s gaze turned serious as the king tried to hide his anxiety.

Harisena cleared his throat and chimed in, as he had to. He never liked Varahamihira getting all the attention. ‘The emperor wants to know what you see in the future.’

Varahamihira spoke haltingly, measuring his every word, ‘There is more glory to the empire. This dynasty will see peace and prosperity; your enemies will be conquered.’

Then he paused, as the bells rang on. Finally, he shook his head. ‘I cannot lie to you, O king. There will be glory, but there will be war too. The blood of many will be spilled.’

‘Do not say this, acharya,’ said Harisena in some alarm.

The king held his gaze and calmly interjected, ‘Let us hear the acharya out. After all, his advice has always helped us.’

Harisena nodded, bowing his head in acceptance. ‘My lord, forgive me.’

The acharya continued, ‘There is an eclipse due, right at the time of your child’s birth – when the earth will wipe away the moon. But then Mangal, the god of war, will wipe away the moon in turn. Mangal’s presence does indicate war in your future – a war that may harm your family. Not your kingdom.’

The import of his words was not lost. Samudragupta gazed at Varahamihira, his face betraying his inner turmoil. ‘What do you suggest, acharya?’

Harisena burst in as if he could not help himself, ‘My lord, there is no such thing as destiny. I am sure humans will play a far more crucial role. We must act according to our best intentions. Vishnu will then heed our call.’

Varahamihira smiled absently. His mind, it seemed, was already on the future. ‘The son that will be born to you will be brave, and there will be tales told of his sense of justice for years to come. But he will have to struggle. There will be bitterness.’

The king sat down, reached out for his veena and began to idly pluck its strings. At long last, he looked up. The bells had begun tolling again. ‘Acharya, you said you wanted to return to your ashram?’

‘Yes, my king. I need to complete my work on numbers. I must get the calculations right to be more certain of my predictions. I think I will be gone a long time.’

The king looked at his two trusted advisers and nodded. ‘Do you promise, then…?’

The king did not have to finish his sentence; the guru understood. ‘When you think it’s right, I could take your second child back with me. There, he shall learn skills required in battle from the mountain warriors. I’ll educate him as a scholar, though there is only so much I can teach. What can I, on my own, achieve when here he would have had the best teachers in the land?’

The king rose quickly, as was his wont. He wasn’t one to ever waver from making quick and sometimes hard decisions. ‘I must go to the queen…’ he said.

Harisena looked worried. ‘My lord, hadn’t we better think about this? We don’t know if the acharya is right.’

Samudragupta shook his head. ‘I cannot take a chance with Magadha. I must be responsible and do all I can to maintain peace in the land.’

For Samudragupta, at this present moment, the past and the future had merged into one. It had all to do with the prophecy, about the prince yet to be born, the one who would change the story of Magadha forever more.

The prince was born around midnight after a hard and difficult labour. It was later said that he struggled for breath and it took the efforts of the best midwives to revive him. Everyone blamed it on the strange celestial behaviour so apparent in the unusually pitch-black night sky. But they did not know what the acharya did – that the moon was taking longer to appear because Mars had cast its shadow over it as well. It was a rare celestial occurrence. And so it was that Magadha was silent the night of the prince’s birth. The palace attendants and midwives agreed. It could not be more inauspicious.

When the prince turned one and his health remained delicate, the king decided that it might be best if he was sent away in the care of nurses to be brought up in acharya Varahamihira’s ashram. The prince’s health was proving to be a concern. The queen too couldn’t help but compare her two sons. The rose- cheeked, cheerful older son, who was now four, and this sickly, frail boy who had seen through his first year with difficulty.

One night, the king walked into his queen Dattadevi’s chambers, determined to speak to her about the decision he had made about his younger son. He found her looking out at the moon through her windows, their edges carved with delicate figures, and the soft cotton curtains grazed her fingers, as she threaded them through her fragrant hair.

‘It is very hard to believe that you named him Chandra,’ said the queen, as she turned to face him with a smile that made her the loveliest woman Samudragupta had ever seen. Her diaphanous robe made by the skilled weavers from the east lay delicately on her shoulders.

‘It is for him to have the blessing of the moon god. The moon may have stayed away at his birth, but the moon god will always be there for him,’ he smiled back wistfully. Their younger son, they both knew, had been named after two brave warriors: the legendary Mauryan king, as well as Samudragupta’s father, Chandragupta, who had established his own rule over Pataliputra.

‘Are you worried for him? My lord, haven’t you much to worry about already?’

‘I worry more about Magadha. It is just one state among others. There are kingdoms afar, with more resources. I’d like Magadha to reach up at least to the river Yamuna in the north.’

‘Two sons fighting for you will make it possible.’

‘Two sons fighting each other might make it impossible.’

The import of the king’s words was not lost on her. As Dattadevi looked enquiringly up at him, he bent towards his queen and ran his fingers through her hair, loosening her braids. The fragrant jasmine flowers brushed against his fingers, and fell at their feet. ‘If our sons are to survive and, more importantly, thrive, we must prepare them for different paths. One to rule, one to fight and support. They must grow up separated. Chandra’s health seems to suffer here. Pataliputra is where the crown prince lives. It is for their own good.’

The queen turned pale.

‘Do you trust me?’ The queen nodded at the king’s urgently whispered question. He went on, ‘Perhaps another place will suit Chandra better than Pataliputra, where things can get hot, wet and cold in the different seasons we experience. Somewhere in the hills, maybe. It will help him, help you recover, and it will help Magadha.’

He saw the confusion and then, moments later, the relief on her face. He had sensed her worry and fatigue over her constantly ailing younger son and he knew she already had a favourite in Ramagupta. Samudragupta felt sadness at this unfairness to his younger son. Already, he was starting life at a disadvantage. But Samudragupta hadn’t forgotten the acharya’s words – that Chandra would be brave and just no matter what he faced – and the king felt a sudden rush of affection for him. In his own way, Samudragupta was determined to protect his son. He knew the palace and its ways; he knew how it changed people. Chandra would grow up a better person by being away from it all.

Perhaps the queen’s relief, her favouritism, was just as well. It made things easier, clearer.

‘Chandragupta will have good teachers. He will learn the role that is right for him,’ Samudragupta declared with more certainty than he had felt about anything in the past year.

On the day of the departure, the prince, accompanied by a few palace helpers, and two wet nurses, prepared to leave in a specially prepared chariot. The carriage was secured and protected by a veil of thick blankets so that the cold forest air would not reach the young prince. The acharya Varahamihira, who had arrived in Pataliputra only some days ago, bowed before the queen as the moment came for the entourage to depart. ‘Thank you for entrusting your son in my care, O queen. I assure you your son will be safe and well. He will be valorous and will never let Magadha’s sun dim. He will, in time, be known as Vikramaditya – his glory will shine like the sun.’

Noting the puzzled expression on the queen’s face, he relented. He had been told he was always too obscure, that he frightened people with his knowledge. Now, he hastened to add, ‘Rama will have a worthy younger brother. Just as Lord Rama had his brother with him always.’

1

A WARRIOR FOR MAGADHA

The narrow river before Chandra leapt, untamed and wild, its waters tumbling roughly over sharp rocks whose needlepoint edges were just visible. Through the misty flecks and the thin drizzle of rain, Chandra could barely make out land on the other side. The Mahanadi was the most illusory of rivers – much smaller than the majestic Ganga or even the Subarnarekha, but far more treacherous. During the rains – which had come early this year – the Mahanadi’s waters had swelled in just one tithi. What had been a calm ribbon of water in the morning had become a raging, seething, grey mass by the afternoon. The ripples close to shore winked deceptively as they caught the misty light, and the lines of current in the river’s middle were dangerous enough to sweep away a full-grown elephant.

Chandra, or Prince Chandragupta, as all the empire’s proclamations and scrolls called him, stood listening to the river, his attention wandering briefly to the voices around him – voices raised in warning, alarm and confusion. He looked preoccupied, staring undaunted at the laughing waters, his back to his soldiers, rigid and straight.

A boat caught unwary had been swept away, taking with it its few passengers. That was what had just happened, the prince had been told. ‘O prince, maybe we need to turn back,’ some of his men advised.

What they did not say, or left tactfully unsaid, was that the ashwamedha had been a bad idea or that, at the very least, it was badly timed. His father, the great Emperor Samudragupta, had just performed the yagna, calling on all kings in the region to recognize the superiority of Magadha and the generosity of the dynasty. The great prayer before a huge sacrificial fire had lasted one tithi and now here he was, the younger son, leading the magnificent horse whose original homeland was somewhere beyond the seas, and was now to all the lands the Magadhan army traversed a symbol of the empire’s magnificence.

There had been dangers they had encountered, though largely from the natural world than from kings they had conquered. The prince, as well as the soldiers who travelled with him, had seen the plunging waterfalls of the Dandakaranya, whose steamy mist eroded visibility over a considerable distance; the herds of wild elephants that could bore through high wild grass; the forests with their hidden treacherous swamps; the caves deep inside the ancient hills peopled by wild creatures; and, occasionally, wandering bands of ascetics, who – as stories went – could fly into a terrifying rage if disturbed. But there had been nothing as daunting as the river now before them. It posed an impossible challenge.

Emperor Samudragupta was ambitious but there were some who now said, with some measured tact, that the ashwamedha had been held too early. He should not have believed some of his court advisers who, with their esoteric knowledge of the stars, had predicted that the next few ayanas of the moon’s cycle could be glorious. Of course, this prediction had received the king’s approval only after Varahamihira, the greatest priest and astronomer of them all and once Prince Chandragupta’s teacher, had confirmed these calculations. Only then had the yagna proceeded.

When the acharya had returned to the palace after long years away, Chandra had welcomed him with joined hands and bowed head. Moments after the rituals of the ashwamedha yagna had been completed, the prince had set out immediately with the horse Tejas, leading the Gupta army as its commander. He had taken the acharya’s blessings before leaving. ‘Return as Vikramaditya. Be as victorious as the sun,’ the sage had whispered. The horse was a prized possession, gifted to Samudragupta by merchants from central Asia. Horses from the grasslands beyond the great Himalayas were known for their speed, the glazed sheen on their coats and the majestic way they tossed their mane as they rode through tall grass. The horse now represented the glory of the empire and the ambitions of Samudragupta.

The acharya’s words had comforted the prince. Though only a day apart, it seemed there was a universe of differences between the ashram at Lalitapatna, where he, Chandra, had spent his early years, and the palace at Pataliputra, to which he had returned as a youth. He had left the palace as an infant, and had been away for a decade. Things in Pataliputra were more sedate, more formal. And there were rules. There was a measured way of speaking, and a rigid hierarchy of procedures and protocol to be followed. In the beginning, Chandra had been impatient, even irritated, by this new life, but his acharya’s last words of advice, given to Chandra when he had left Lalitapatna for Pataliputra, had helped him cope.

‘Be patient, Chandra,’ the guru had said. ‘You learn much from being a quiet observer.’

Chandra understood that the formality of rules and customs were essential parts of a king’s own power for these added to the prestige of the court. But his brother, Ramagupta, whose hostile looks Chandra remembered especially well the first day he rode in from the ashram, was making things increasingly difficult for him. Ramagupta had basked in his parents’ affection for so long that when told of the return of his younger brother, he had been filled with deep resentment. His childish envy ill-suited his role as the future king of Magadha; Ramagupta made little effort to hide his dismay, or his contempt for Chandra and what he felt were Chandra’s country bumpkin ways. Now Ramagupta made it his business to ensure that every court rule was enforced and correctly followed. He especially enjoyed pointing out Chandra’s minor transgressions on such things.

Rules mattered, Ramagupta often declared, for everything to run efficiently, and so he had appointed scholars to codify rules and rituals that would define life in the palace and of its officials. The enforcement of these just awaited his father’s sanction. The fact that the emperor had thus far had little time to vet these proposals only added to Ramagupta’s ire against his brother. Ramagupta felt his father, his heart set on the ashwamedha yagna, was spending far more time with Chandra. Days before the yagna, the king had been spotted riding out with Chandra on long hunting excursions.

The ashwamedha yagna was an occasion that involved the entire royal family. Ramagupta had taken it upon himself to plan the rituals and rites associated with the yagna – that it would be Chandra leading the majestic horse, Tejas, on the campaign into alien territories hadn’t been Ramagupta’s intention. Yet, Chandra had instantly agreed to his father’s proposal, his eyes lighting up at the prospect of pleasing Samudragupta. In the end, however, Ramagupta had not demurred. Only later did Chandra realize that his brother had only agreed because he was glad to have Chandra away from the palace. Moreover, Ramagupta did not expect much from him. In that respect, Chandra’s lips twisted at the thought, his brother would indeed be greatly surprised.

In other ways too, Ramagupta had endeavoured to make the occasion his own. He had persuaded their mother Dattadevi to make one more pronouncement – that of his engagement to Dhruvadevi, the daughter of Harshagupta, Samudragupta’s trusted general and their distant cousin.

On hearing this, Chandra had turned red with shock and embarrassment. The memory of this humiliation burnt him even now, days later, when he was several kos away from Pataliputra.

Chandra had met Dhruvadevi when he had first visited her father’s palatial home in Pataliputra. He had been instantly drawn to her stunning beauty. When he had visited her again, too soon, she had smiled teasingly as if guessing his intentions. That was when she had asked him to prove himself to her.

‘As a kshatriya, you are supposed to prove yourself, regardless of the occasion,’ she had said, leaving him puzzled at the ways of the palace and its sophisticated, beautiful women.

However, he had acquiesced, and then, for the next few days, had completed for her the oddest, yet the most demanding kind, of errands. He had ridden all the way to Devgarh to collect on her behest, some special offerings from that city’s old temple. Then, he had hunted down and fetched a white boar’s tooth for her. When news of his interest in Dhruvadevi reached Ramagupta’s ears, he had summoned them both and demanded an explanation, but she had simply laughed it off in the enchanting way she had.

Then, holding out a jasmine flower towards Ramagupta so he could thread it into her braid even as Chandra watched, she teased, ‘I did it all to test out your brother, Rama. After all, it is the younger brother’s duty to protect whomsoever his older brother holds dear.’ She added that Chandra had insisted on doing it. For he was the warrior, and Rama the scholar.

‘The scholar makes rules; the warrior follows them.’

Then both his brother and Dhruvadevi had laughed, in a strangely derisive way. It was clear to Chandra whom she considered the superior figure. Blood had rushed to Chandra’s face, and he had felt left out.

Still, he had been taken by surprise at the unexpectedness of the announcement. He tried to forget this feeling of hurt and humiliation by telling himself he was a warrior above all else, yet it was difficult to not dwell on the derision and condescension he seemed to evoke in his brother and now soon-to-be sister-in-law.

Still, in a way Chandra was glad. The engagement sealed the matter once and for all, and erased his confusion. He marvelled at Dhruvadevi’s capacity for deception. He now understood far more about the world; things he had learnt beyond his experiences in his guru’s ashram. The ways of war were important, he realized, but so was the need to understand human behaviour. The latter would always prove challenging – observing and listening to a person always revealed their vulnerabilities, their convictions. It took time and patience but for now, Chandra was happy biding his time.

At the moment, however, he had bigger problems that needed solving. After the ashwamedha ceremony, the prince, with his army in tow, had left for Gaya and Pundravardhana to the east, with the magnificent horse Tejas always riding ahead of the prince’s chariot. The plan was to head east, seeking allegiance from the rich and powerful kings whose territories ringed the sea. If they resisted, there would be battle. Chandra was prepared but he would take things a day at a time. There was nothing Chandra liked more than to race uphill with the horses and through the narrow trails that made up the mountains of the Dandakaranya. They had made good time thus far, but now found themselves confronting the treacherous waters of the river Mahanadi.

Chandra rode his chariot along the river’s edge. The rains had stopped but a thick fog hung in the air, making it difficult to see the other side. The ribbon of water rose against his chariot wheels, almost in mockery.

Then the prince did something that drew a gasp from every man in his army. He plunged his chariot into the rough waters, hearing its wheels crunch against the rocks, the water churning noisily. He had identified the spot where the river. He knew it was dangerous, but this was the only place from where they could cross it.

The chariot swung around as it fought against the river current, and Chandra’s men held their breaths as the horses thrashed, kicked and reared up, the reins secure in their prince’s hands.

‘The river can be tamed,’ he declared as he returned to the shore, his lean arms holding the reins casually, calming the horses. ‘There can be no going back now.’

His men had no option but to listen as he stood tall in his chariot, his head nearly touching its roof, his dark eyes resting on every one of them as he spoke. Jumping down effortlessly from the chariot, he unbuckled the horses, patting them, speaking to them in low whispers. He then oversaw the dismantling of the chariots by his men so they could be assembled into a raft. He alone would lead the yagna horse across the river. The horse was already dear to him, and he had named it too: Tejas. The horse was the king’s representative, and so Chandra could lead the horse but not ride him.

‘We can do it,’ he told his men, his eyes shining as the raft bobbed and dipped in the waters. ‘The moment is what matters. And news of capitulation travels fast,’ he added.

Chandra remembered well what he had heard of the Kosala king, whose kingdom lay beyond the river. The king Prasenajit was said to be brave but there were also rumours that he was ready to abdicate and renounce his throne, that he considered himself merely a guardian of the throne and was only ruling because his people wanted him to. It was information Chandra had gained as he travelled east with his army; news gathered from merchant convoys and bands of wandering monks or bhikkhus. Information that contradicted what Magadha’s foreign ministry had learnt about the Kosala king’s large army.

It was only when they were midway across the river that he saw on the other side behind the shimmering curtain of white mist, a small gathering of troops. The clouds parted for a moment and the sun peeped out languidly, making the brass roof of a chariot shine. Then, over the heat and the mist, Chandra saw the white flag that now fluttered in the wind – the same wind that made the waters swirl and the raft heave and bounce erratically.

After long moments, the raft touched the shore on the other side. Chandra stepped on to a rock on bare land, pulling the horse’s reins along as his men rapidly sprang into action, securing the raft as well as forming a secure ring around him. An older man stepped forward; he had a commanding stride but a welcoming smile. It was Prasenajit, the king of Kosala himself. A slender man with his silver hair held in a gold wreath, he now turned and gestured to the men who flanked him, their spears lowered, indicating that they were only there as a welcoming party. Chandra noticed how they left the horse alone, an acknowledgement that they would not dispute Samudragupta’s superiority. That was the sign he had been waiting for but he still had his guard up.

‘O prince, we welcome you to the land of Kosala. It is not our intention to hold your horse. Our kingdom is smaller than the mighty Magadha empire, but our two kingdoms can be allies and our forces will always fight with yours.’

The king bowed as he finished, and the prince reciprocated. The king then handed over his sceptre, a symbol of his acceptance, and held his arms out. The prince acknowledged the embrace and, in that wind and rain, the conch shells blew and the drums echoed the joy of the moment.

The party headed to the palace that stood secure and protected behind a hill. Later that evening, while his men set up tents in the courtyard, the prince of Magadha and the king of Kosala met in the palace’s inner chambers and signed accords to ensure eternal friendship between Magadha and Kosala. The prince bowed before the Goddess, a symbol of the river that ran by the kingdom, and offered, in turn, a silver urn containing an offering made to Vishnu, Queen Dattadevi’s chosen god. The king Prasenajit enveloped him in a warm embrace as the court singers sang paeans to the heavens.

‘O prince, you are not just worthy of your father but you would do the great Chandragupta proud as well.’ Prasenajit smiled.

His words made Chandra’s heart beat faster. That was his dream, to be a warrior as magnificent as his own grandfather, and as heroic as the legendary Mauryan ruler. Wary of the sneering look on his brother’s face, this, of all things, was what he had sworn to keep to himself.

‘I do not deserve such epithets, my lord. I serve my father and Magadha.’

‘And you grace my land, O prince.’

Chandra thanked the king for the lavish welcome. He spoke to his men from the ramparts, flanked by the king Prasenajit and the Kosalan ministers, assuring his soldiers that they could sleep in peace. He listened to the sounds of the resting, tired horses and promised to visit Tejas, the ceremonial horse, just before he slept. He had grown fond of the horse an

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...