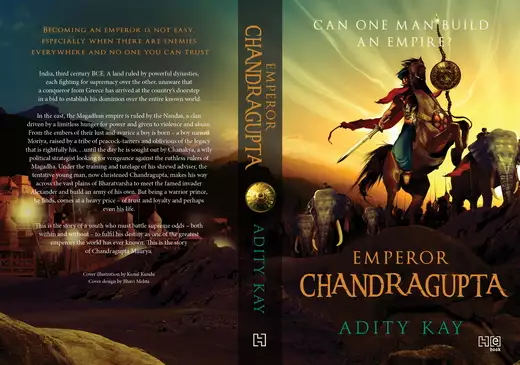

Emperor Chandragupta

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Becoming an emperor is not easy, especially when there are enemies everywhere and no one you can trust. India, third century BCE. A land ruled by powerful dynasties, each fighting for supremacy over the other, unaware that a conqueror from Greece has arrived at the country’s doorstep in a bid to establish his dominion over the entire known world. In the east, the Magadhan empire is ruled by the Nandas, a clan driven by a limitless hunger for power and given to violence and abuse. From the embers of their lust and avarice a boy is born – a boy named Moriya, raised by a tribe of peacock-tamers and oblivious of the legacy that is rightfully his...until the day he is sought out by Chanakya, a wily political strategist looking for vengeance against the ruthless rulers of Magadha. Under the training and tutelage of his shrewd adviser, the tentative young man, now christened Chandragupta, makes his way across the vast plains of Bharatvarsha to meet the famed invader Alexander and build an army of his own. But being a warrior prince, he finds, comes at a heavy price – of trust and loyalty and perhaps even his life… This is the story of a youth who must battle supreme odds – both within and without – to fulfil his destiny as one of the greatest emperors the world has ever known. This is the story of Chandragupta Maurya.

Release date: September 27, 2016

Publisher: Hachette India

Print pages: 408

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Emperor Chandragupta

Adity Kay

The arrow sliced through air, turning silver on catching the light. Moriya stood below, crinkling his eyes, watching the arrow rise, following the sharp line of the mountain ridge.

He knew it would get the eagle before that magnificent bird was even aware of the arrow streaking towards him. This eagle, like others of its kind, was alert – its senses catching every nuance, even the slightest movement on the earth far below. But the arrow’s rise mirrored the whistling wind, its silver was that of slanting raindrops, or a ray of sun, unexpectedly bright. Even an eagle as splendid as the crested hawk-eagle, with its defiant raised hood and burning golden eyes, stood no chance.

From below, Moriya’s eyes locked with the eagle’s. He saw the fire bright in its eyes one last time as his arrow pierced its throat. He heard the majestic bird’s last squawk before it hurtled to the earth, falling past him, and he caught the smell of life as it left the bird. It was the smell of the earth around, the hard old rocks, the dry grass and the wind that blew in from far away, and as the bird died, it seemed to Moriya, it took a bit of the earth with it.

As Moriya stood on the ridge, he was unable to ignore the plaintive cheeping coming from the nest atop the hill. He had climbed the hills called the Aravallis at the very edge of the desert because he had heard how much of a fight these birds could put up. It was a challenge he had been unable to resist. The other boys, his companions in the tribe of the cattle-herders, had not stopped him. They knew by now that Moriya did things on his own, and they followed him wherever he went. It had always been like that. He was one of the cattle-herders and yet not really one of them.

The crested eagles were lone, wilful and lived solitary lives. He was like them in many ways. The cattle-herders lived close to the plains of the Punjab. They had moved up from the region between the ravines and the desert to the west. Saurashtra and Avanti lay southwest and south, and the river Yamuna ran east, close to the kingdoms of the Matsyas and the Surasenas. Every year they marched this way, up to the pasturelands in the northwest. But now all was uncertain, for there were reports that an invader from a faraway land in the west was very close, just beyond the mountains of the Malayavats and Nishadas. Word was that these foreigners, the Yavanas, led by a golden-haired king called Alexander, could cover immense distances on their quick and strong horses in a matter of days. No king stood a chance against them. People were fleeing towards cities, seeking shelter behind high fort walls, whereas those used to a life on the move, the nomadic herders and other forest tribes, were biding their time, stopping often, reading the signs before moving on.

Every day, the boys, with Moriya in the lead, rode out into the wild scrublands, hoping to meet other tribes or groups on the move for any news about the invader. On one of these mornings, the eagle had appeared, fierce, insistent and far too quick as it snapped repeatedly at a newborn calf before flying away. Moriya had known instantly that he would match himself against it. His eyes had seen how far it travelled, and he gauged he would have to trap it close to where it nested. An animal is always more vulnerable closer to home. In his life on the move, he had learnt that.

Now he climbed, a brutal, rough climb, till he reached the nest, and stopped abruptly. The others below saw him stumbling, the cattle grazed lazily and everything seemed still, but there was that unmistakable tension in the air. It seemed a timeless, short moment between life and death. Only Moriya knew that he had held his breath, felt his fingers quiver as he saw the fledgling the mother had been trying to feed and protect.

He picked it up, looking down as its wide yellow eyes stared, helpless, back at him. This young bird would soon grow up to be as ferocious a fighter as its mother. She could have flown away, he realized now, but had stayed close to her child in the moment of danger. Whose was the greater courage then – his or the eagle-mother’s?

The boys chanted his name as he descended in their midst. They were all around his age, with similar dust-encrusted faces, for the journey had left its mark on everyone. Lines ran deep on their feet and their skin bore scratches. All of them, men belonging to roving, wandering tribes, were now being forced to choose between kingdoms. To the east were the Nandas, and to the west the threat of Alexander and his vast army. Anyone determined to fly alone would perhaps meet the same fate as that magnificent eagle.

He saw his companions raise their spears in salutation, he heard their cheers. There was something about Moriya’s expression that made them quiet down. No victor could look so forlorn. Then they saw the little eagle he clasped in his hands.

He sat on an old stone seat streaked with mud and dried leaves, crawling with ants, and shadowed by overhanging pipal branches. It was perhaps a place where a sage had once meditated. Now it was a throne where Moriya sat – he was their king. And even if it was all an act, the boys were all willing participants, for when Moriya sat there he told them things they had no idea about, things that took them farther away from anything they had ever known. Moriya, with eyes that could look piercingly fierce one moment and broodingly intense the next, had the answers and always more questions – questions bigger than mere everyday matters.

‘Tell me,’ he asked the boys, ‘do you think, if I had known about this small bird, I should still have killed the eagle?’

‘That big eagle was a nuisance. Remember how she would swoop down to snatch our food away? And she troubled the priest to no end,’ said one of the boys.

‘True, but maybe she could have been driven away.’

‘That’s what the priest says, too. He says time and again the bird came back.’

‘Because of this one.’ Moriya nodded at the bird cupped in his palms. The boys fell silent at the seriousness of his voice.

‘So what is to be done now with the little one?’ Moriya asked, looking down at the young bird resting quietly in his hands, as if it was assured of protection.

‘You must kill it,’ one of the group piped up. ‘After all, he will grow up to be a ferocious fighting bird.’

‘And these birds can never be tamed. The priest tried it as well,’ said another.

Moriya persisted. ‘But it is helpless. Should it be denied care simply because it will turn into a killer? We could kill its parent because it resisted us. But this…?’ As he mused over this dilemma he said aloud, ‘What would a king’s duty be?’

They had no answer but began talking all at once.

‘Kings kill those captured in war, or throw them in dungeons,’ said one of the boys again, ‘because the fear of revenge is constant in their minds.’

‘But this is a bird... it is young and helpless. We must take care of it because it has no one,’ said Moriya. ‘It is our duty, our dharma.’

‘Do you think we can tame the bird and present him to Alexander?’

The question from one of the boys made the others laugh raucously.

‘Would he really want an eagle, or demand a lion?’ another boy piped up.

They laughed again.

‘This eagle stays with me,’ Moriya said, in a quiet voice. ‘I will use him to send a message to Alexander.’

‘A message?’

‘Yes, ask him to leave our land or challenge him to a duel to see who is stronger.’

No one laughed this time. Just months ago he had challenged them all to a battle where sticks shaped out of fallen branches served as their weapons. He had taken them on together, and even singly, and finally having beaten them all, offered his hand in help to his fallen victims. His arms had moved faster than anyone else’s; he had jumped, whirled, turned around, his stick falling surely and certainly while they had missed the real thing for the shadow many a time. The way he had struck and aimed had never hurt but he had disarmed them surely and effectively. They had been mesmerized by his accuracy and quick movements, and understood with certainty that they had to follow him from then on.

‘Yes, a duel.’ He had a faraway look on his face now.

Alexander. The name reverberated in his head. Alexander. The man who, it seemed, would conquer everything in his path. Who would travel to wherever the world ended, having conquered everything behind him. He made the world seem even bigger than it was – seas, mountains, deserts – all vast and mighty, all waiting to be claimed. Moriya felt his heart race and his eyes blazed. Far away, the wind in the trees made the branches move as if an invisible army lay hidden within them. Alexander. One day he would meet him. One day…

1

A Rare Bird

The land throbbed as the horse galloped over the arid land towards the forest. Moriya knew of the hard rocks concealed below the dry grass, rocks that were far older than the cold Himavat mountains to the north, beyond the land of the five rivers that was the Punjab. Craggy old trees whizzed by, but in the near distance were low hills, small shrubs and miles of wild grass that cattle were grazing on. As he rode on, the colours on the rocks changed, keeping pace with the sun’s movement on the horizon. Moriya rode on, swift and graceful on his horse. The animal was a mere pony, ordinary brown in colour, but Moriya rode it with a majesty and poise that came naturally to him.

He was on the trail left by the peacocks, sighting their soft, silken feathers strewn amidst the rocks. His keen ears had caught their long melancholy calls earlier, more melodious than he had ever heard before. He had wondered whether he had heard right. Was that the cry of the green peafowl – the rarest of rare among birds, far more precious than its cousin, the ordinary blue peacock – its sea-green plumage turning a gorgeous emerald every time it flashed in the sun?

He stopped to watch as the sun rose in slow motion beyond the rocky hillocks that stretched ahead of him, conscious of that one perfect moment before time rushed on. His horse stomped impatiently, flicking its tail nervously. Moriya took a quick look behind him, his eyes straying down the rocks. He could see the ripple of the small stream that flowed close by, a ribbon of water that had appeared when it had rained unexpectedly, and would just as soon vanish. To the west were the dry forests, where he was headed. It was his father who had first told him of the peacocks and Moriya knew he would find them again among the jamun and banyan trees around the abandoned temple at the far end of the hills. Beyond the temple was the desert, a stretch of sand and thorny bushes, uninhabitable for long distances.

Riding up a hillock, he scanned the horizon again, turning his horse around in a perfect circle on a narrow point without missing a step. The wind rose, grainy but soothingly familiar. From this height, Moriya had a view of the world as he knew it. To the southeast lay Magadha, with its capital at Pataliputra, the city by the Ganga. For him, it was always far away, further than his eye could see, though never far from his thoughts. He lived with the certainty that one day he would return to Pataliputra, a city whose rulers had taken away everything he had known and cherished, a city that had taught him the futility of having attachments or lingering memories. A city, he acknowledged, unlike any other place he had ever heard about or seen since. A city he would love to rule from. One day.

He urged his horse on, knowing it was better to chase the peacocks than to give in to thoughts that had no end.

He remembered the first time he had laid eyes on the elusive bird. He had been a few years younger then, reaching only up to his father’s shoulder, and was accompanying him on a journey to the forests that skirted Magadha to the north. It was the region where the smaller republics of Malla and Vajji had once existed, long before Magadha became the powerful kingdom it was. The great and greedy Ajatashatru, the emperor who lived in the time of the Buddha nearly two centuries ago, had taken them over, ruthlessly and with cold logic.

His father, chief of the Moriyas, the tribe of the peacock-tamers, had taught him almost everything he knew. That afternoon long ago, Moriya would learn more from his father than he realized. They were in a small row boat, moving in the slow current of the Ganga, banked by forests that were the most dangerous of all forests known, and denser than the forests to the west he now roamed in. Rising dark and thick, green overhanging branches mingling with thick brown weeds that grew taller every year with the rains, the forests of Moriya’s younger days ranged from the eastern borders of Magadha all the way to the Himavat mountains. They were peopled by wild elephant herds that could pound through without warning. The speed of the herds always belied their size; they could cross vast stretches of forest in a day. The earth shook and trembled under the massive feet of a hundred and more elephants in spate. Wild buffaloes and deer lived where the forests were less dense, and the elusive tigers had been seen here too.

His father’s eyes narrowed as he scanned the forests that came right up to the river bank. The bittersweet smell of sal and tamarind trees reached them, mixed with the feral scent of forest creatures. Moriya noted the way the trees’ branches bent towards the water and the stillness of their leaves.

‘These forests…they look as if nothing can ever disturb them. Animals can stay hidden forever among these trees; unseen, living their lives just as nature intended,’ his father said as they rowed down the river towards Pataliputra. ‘But there are some people who will not rest until they tame its creatures, even the magnificent elephants – all for their own ends.’

His father’s lips twisted bitterly. He was referring to the Nandas, the current rulers of Magadha, who were intent on destroying the forests and the tribes who lived in it, simply to get their hands on more elephants for their mighty army. As if in acknowledgment of his father’s words, there came a loud trumpeting sound from within the forest. Moriya could tell from the way the trees heaved and shifted that a herd was moving through the forest. He rowed faster, gripping the oars tightly and bending forward to exert as much force as he could.

It was then that they heard a long-drawn-out haunting cry pierce through the calls of the elephant herd and the other sounds of the forest. It was a cry that stretched through the expanse of trees and made his father sit up straight and go still in a way Moriya had never seen before. ‘That call…it can belong to none other than a green peacock,’ his father said in an awed whisper.

Indicating that they must move on, his father guided them shoreward. His father knew where the boat could be anchored securely, just as he knew each path leading from the river through the forest. They proceeded into the vast green, Moriya leading the way, reading the elephant tracks the way his father had showed him. He paused to listen to the sounds of the forest, sniff the air, and break small dried branches to make their way back easier.

Quite unexpectedly, they came upon a clearing in the forest, and that was when both of them caught sight of the bird – the most beautiful bird Moriya had ever seen, perched high on a branch. In the light of the sun shimmering through the canopy of trees, the bird’s wings changed colour, shifting from green to blue and then green again, an iridescent dancing patina of green that lit up the trees – its colours always distinct from the leaves that closed around it. The bird stretched out its long slender neck, beat its tail gently on the branch, then called again, a long cry that floated upward, the leaves parting to carry the sound to the skies above.

Let it be. Let it be. Moriya heard his father’s soft murmur in his ears.

All they could do was look on, knowing for that one moment the eternal truth – that every creation is unique and wonderful. Every part of creation was worth cherishing and destruction was futile. This was precisely what the Buddha had said.

The moment passed. The bird suddenly turned its head towards them, startled, as if it had sensed their presence, then gracefully hopped off the branch and flew upwards, its wings glittering a luminous green, shaping into a blur as it disappeared into the blue sky.

In its wake Moriya saw a feather float gently to the ground. He picked it up. It seemed to throb still with the peacock’s life blood.

‘What a beautiful creature...’ his father whispered.

‘Do you know about it?’ he asked his father.

‘Yes,’ he nodded, ‘but you and I are going to keep this a secret. Birds like this one will never be trapped or hunted down. They will roam free, always. Never kill any bird, son, unless it is essential. They make the world beautiful and complete. All creatures – animals and birds and all of us too – are meant to live together in harmony. We are all interconnected. This is what great men and sages have taught us, men whose words will live longer than kings’ will. True power lies in understanding that life and death assure the continuity of the universe itself.’

Moriya had, he thought then, understood what his father had meant. Over time, he came to realize there was more to his father’s words. Chief of the Moriyas of Pippalivahana, his father believed their tribe was meant to protect birds, to prevent any harm from befalling them. They were the caretakers of the birds and the forest they lived in, he had always said. Moriya took a deep breath, remembering his father’s solemn voice. Of course, there were the truths of his father and there were those that Moriya had to learn now that he was older – that killing was necessary, because it proved one’s might. Two strong creatures, man or animal, could never rule over the same realm.

Four winters had passed since that journey with his father. Moriya was now far from the forests of the east, where he had spent a little over eleven years of his life. He missed his father, and wondered what he would have had to say now that Moriya had once again sighted the magnificent, elusive green peacock.

This time he corrected himself, fiercely, shaking his mane of dark curls so they lashed against his back. Don’t call him ‘Father’, not anymore. Call him ‘Chief’ and think no more of the past… Think no more. He knew this – that his past was not really his to claim, but there was a time for everything, and the time had come for him to know at least a few things with certainty. He could sense that the boys who were his everyday companions thought he was different from them. And he was, because they had assured pasts, and no doubts and questions about where they belonged and about who their parents were, while he on the other hand was not sure of anything, not even after four winters of being on the run.

Moriya followed the bird with renewed intensity. The brilliant blue-green of the peafowl’s feathers was a stark contrast to the grey rocks, brown boulders and the dry keekar bushes of the Aravallis, the biggest and oldest mountains in these parts. It was difficult to lose sight of the bird – it flew low at times, its wings making slender shadows against the rock, and then rose high, its colours a shimmering green as the day lengthened, the sky turning from a gentle morning blue to a raging gold. Squinting against the harsh morning light, Moriya glimpsed the temple again, closer than before. Built by passing herders, it stood amidst a copse of trees, its stone walls blackened with time and the heat of the desert.

He picked up his bow, the taut bowstring whistling in a shrill imitation of the wind as he drew his arrow across. Did he dare aim his arrow at the bird? For a few moments Moriya toyed with the idea. Then he shrugged and let his arm fall away. The arrowhead grazed his horse’s mane and the animal shuffled in protest. Moriya bent forward, nuzzling its neck in apology. He saw the bird flying away – almost in relief, he thought – heading further south, where the scrubland and the desert gave way to the forests.

He looked around, unsure if his horse could negotiate its way down the rocks and towards the clump of trees. It was young and skittish and would gallop at full tilt on an open stretch of ground, but one wrong step on these old rocks could send them both hurtling down.

He heard the peacock’s call from the forest, which boasted banyan, jamun and amla trees. These were trees of the dry forest, whose brown winter leaves were now turning a golden yellow. Were there two birds hidden among those trees? More? Moriya cupped his hands around his mouth, and soon the air resonated with a melodious, haunting call. Barely had the cry died out when he was rewarded with an answering call from the temple at the edge of the forest. Not one, but two, and then many more. He craned his neck and bent down to pacify his horse, made nervous by the unexpected clamour. The peacocks called again and he saw the branches move as the birds moved about restlessly. Perhaps he should not have disturbed them… Then something else caught his eye.

A tall figure was moving slowly amidst the trees. Moriya became still and watched as the figure limped forward in a fatigued yet determined manner, and a voice from the past flooded his mind – a low, rasping voice that would brook no disagreement, and a pair of glittering, sharp eyes that missed nothing.

The peacocks had brought him here with some intent, Moriya was sure. As he looked on, he calculated that the man would reach the settlement of the cattle-herders, the people Moriya now lived with, by nightfall. Till then he, this traveller from afar, would perhaps rest in the old temple. Moriya dismounted and patted his horse, whispering in his ear as he placed the reins in the creature’s mouth. Go home, he said, go back home. He knew why the other man was here, and Moriya was not going to be taken by surprise – like the last time they had met. In his search for answers, Moriya knew, he would have to be ready to relinquish old attachments.

2

Secret Journeys

That journey with his father held more revelations for Moriya than just his first glimpse of the ethereal green peacock. They had sailed further down the Ganga, the sun sinking in the west, its light a gentle gold on the trees. His father had directed the boat in a distinct southeast direction, and Moriya knew they were headed for Pataliputra, the capital of Magadha, the mighty kingdom ruled by the ruthless Nanda king Mahapadma.

From a distance, the walls of the fortress rose forbiddingly over the lush, thick forest, as though reminding them of Mahapadma’s presence. The late afternoon sun added lustre to the hard brown stones, doing little to ease the menacing appearance of the cave-like windows that jutted out from the highest reaches of the fortress. Cruel and unpredictable, Mahapadma Nanda had expanded his kingdom through intrigue and violence, making it far bigger than when the great kings Bimbisara and his son Ajatashatru had been its rulers two centuries ago. Mahapadma was a man of such great power and strength that it was believed he wrestled with elephants every morning. His footsteps made the earth tremble and his voice, when heard from afar, thundered like a lion’s roar. It was rumoured, in fact, that he kept lions as pets. He was extremely ambitious – the fort grew bigger and his armies did too – but Mahapadma’s quest for more power remained unabated.

When he rose to the throne, the people of Magadha knew they had no enemies to fear. The fort that surrounded the city for miles around was assurance enough of security from invasion. Their fathers and grandfathers had built it, rolling up huge blocks of stone to construct massive walls. With its gigantic columns and forbidding gates, the fort was – along with the surrounding forest, the high mountains to the east and north, and the river Ganga – as sacred to them as the gods they worshipped. It convinced them that, like all their kings, from Bimbisara to Mahapadma Nanda, Magadha was invincible, an empire like none other. But the admiration that the kings had once evoked was now mingled with fear, for to Mahapadma and his sons, the nine Nanda princes, justice and duty came second to supremacy, which they craved at all cost.

This fear had made the people of Magadha incapable of questioning the injustices they witnessed every day and often faced themselves. They knew what had happened to the tribes that had tried to withstand the force of the Nanda armies; how the ancient forests, the free realm of all creatures, were now part of the Nandas’ domain; how hunters were forced to work for the Nanda armies and capture wild elephants to be tamed and trained for war. They knew that anyone who opposed the Nandas or questioned them was killed or picked up and locked in dark dungeons. Some never returned; only a lucky few escaped. They saw how their women, even the free women of the tribes, were made slaves for life, passed from one Nanda prince to another, while the brothers’ lust never satiated. People spoke in hushed whispers of underground cells and deep tunnels where captured rebels were chained and made to guard the treasures that the royals had gathered over the years – treasures they had amassed by levying excessive taxes on the people they ruled and by demanding more than their fair share of crops from peasants.

Moriya and his father were well aware of these cruelties. That day, their boat secured to the overhanging branches of a particularly leafy tree which kept it hidden from view, and the sight of the peacock still fresh in their minds, father and son started moving through the forest. Once in its depths, Moriya dropped down and pushed his ear to the leaf-carpeted earth. He heard the wind blow, the breathing of a thousand and more creatures in the forest, the sound of a leaf drifting down. He knew that if he listened carefully, he would hear a woman crying. That was the sound of injustice.

His father nudged him. ‘We can’t linger, Moriya. Not here of all places.’

They moved on, his father leading the way, deeper among the trees, taking a twisted, ever more difficult path. Through the gaps among the trees, the high walls of the fort appeared closer at every turn. Moriya followed his father wordlessly. He knew how his father had held out against everyone else in the tribe and had not acquiesced to the will of the Nandas, but it seemed they were now heading directly into the oppressors’ domain. They were both armed only with daggers and, if discovered, any contest would be farcical. What did his father intend to do?

The peacocks and other birds were the special upkeep of the Moriyas, the tribe they were part of, the tribe whose very existence was bound to the birds of the forest. They were the birds’ protectors and in a way the keepers of the forest too. But many of their fellow tribesmen were now turning away from that truth. There were some in the tribe who spoke of a compromise with the Nandas. The future of the tribe was at stake if they defied the king, they said. ‘They need birds, and they are rich. Peacocks and pheasants and falcons... It could benefit us if we sold some to them,’ one of Moriya’s uncles said.

‘They need birds that will fight each other to death for their amusement, birds to kill for pleasure,’ his father had replied calmly. ‘Our lives are tied to these birds. We can never betray that bond. They have given us so much. Their feathers are used as delicate quills. Their eggs are ingredients for potions that cure the most resilient diseases. Their beauty and grace gives us happiness. We tame them, teach them to dance to a rhythm so they add to a king’s glory. They are of more use to us than we to them, even the greatest and mightiest of kings must understand that. It is us humans that are far more wretched. We forget these bonds that tie us to every creature on earth.’

‘Your stubbornness will cost us our lives, our livelihoods, and the very animals you seek to protect,’ said another tribesman. ‘What you will not do, their soldiers will. Their elephants will trample through these forests, drive the birds away and then us, too. They prey on the weak, derive their power from emasculating others. And you know this.’

Sensing the futility of more talk, Moriya’s father kept silent, but his mother took a step forward and slapped the face of the man who had spoken. No one said much afterwards. They had always been fiercely loyal to their chief and in their heart of hearts they knew he had the tribe’s best interests in mind. Or so Moriya had assumed.

Now, hiding near the Nandas’ fortress, Moriya looked at his father – a tall, lean man, his face withered and wrinkled, not as much with age as from the years he had spent living out in the open, exposed to the elements. He always had the calm and steady gaze of a man who understood his own morality, a man who knew one kind of cloud from another; who could tell everything about a forest from a fallen leaf; who knew, it was said, the languages of animals.

Now Moriya spoke, unable to stop the question that came unbidden to him. ‘Aren’t you afraid of the Nandas? Their soldiers might find us here any moment.’

‘We don’t have much to pay them,’ his father said, smiling ruefully before sadness descended on his face. ‘And no, I am not afraid. Sometimes a challenge is just not worth it.’

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...