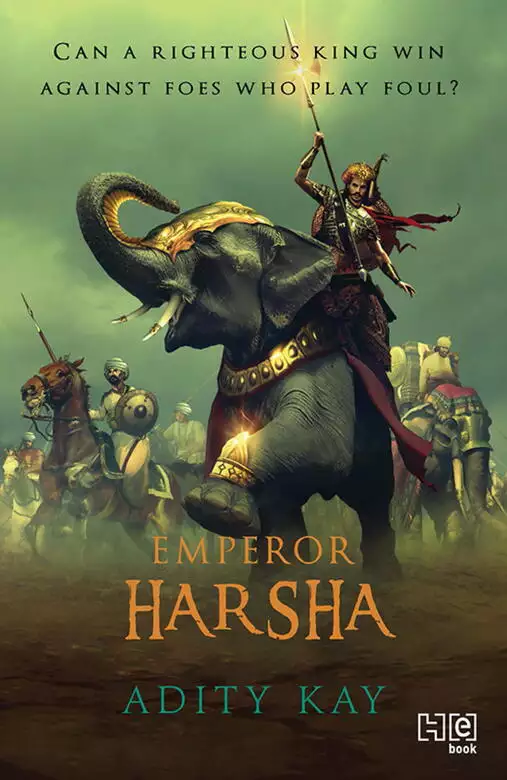

Emperor Harsha

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Young Harsha wants only to be a scholar – but when the crown falls to him, can the reluctant prince rise to the occasion?India, seventh century CE. Harsha, the youngest prince of the northern kingdom of Sthaniswara, is immersed in his studies at Nalanda. As far as he is concerned, the future of his realm is secure in the hands of his brother, the strait-laced crown prince Rajyavardhana. But when the time comes for his sister’s swayamvar, Harsha is compelled to tear himself away from his books – for only a little while, he hopes.Things, however, take an ugly turn at the swayamvar, as Devagupta, king of neighbouring Malava, makes no secret of his ire at not being chosen by the princess. And when their father, King Prabhakaravardhana, dies under mysterious circumstances soon after, the princes fear something sinister is afoot. While Rajyavardhana takes the throne, Harsha sets out to unravel a web of intrigue he suspects spans kingdoms.But his mission is cut short, as war rocks the land and treachery lays low his brother. Burdened with the crown, the scholar prince now has to battle enemies who follow no dharma, exact vengeance upon the devious Devagupta and hunt down the even more dangerous foe pulling all the strings. And as a new force rises to the south, Harsha realizes he must ready himself to face his greatest challenge yet.

Release date: October 25, 2020

Publisher: Hachette India

Print pages: 376

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Emperor Harsha

Adity Kay

The university was like a small town. When Harsha first arrived in Nalanda, unannounced and unheralded, he took much time finding his way around. From his room – reached via a steep flight of steps, and then the long corridor leading past similar rooms – he could look across a vista of buildings, big and small. The shrine with the imprint of the Buddha, the Holy One’s feet, the low triangular mud-brick building that held the classrooms, the first of many pokharas that lay between this and the library, and the shady grove of four banyan trees, where scholars met, gossiped and read to each other things they had just learnt, were all only a small part of the campus. Everything about Nalanda – its size, splendour, the wisdom of the teachers – never failed to amaze Harsha although he had been there four ayanas already.

Harsha intended to remember everything this last season, just before the rains came. It was the season he had to make the most of, for he had to return home, obliging his father, King Prabhakaravardhana of Sthaniswara. His sister’s swayamvar was due soon after the winter harvest, and to him fell the duty of managing it. His older brother, Rajyavardhana, was away in the north.

The morning of the monk Huike’s arrival, the excitement was palpable. The news had spread in Nalanda that a monk from a faraway land had arrived, and the morning meal was rushed. Everyone wanted a look at him. Not only was Huike reputed to be an expert swordsman, his years of meditation had taught him to levitate and even change his appearance at will. No one believed the last bit though, and there was much laughter across the dining hall.

The rumour was that he was from Zhongguo, but Huike himself had not confirmed anything. He did not speak the language, neither Magadhi nor the language of that faraway land across the mountains. But his skills with the sword made up for all that Huike couldn’t say. Harsha heard all this and knew he too had to meet Huike the monk.

For Harsha, the last few days hadn’t been very promising. He had spent long mornings looking at his scrolls, vexed that the play he was writing was coming to nothing. It was about a prince who wanted to give everything up and become a monk. But it was becoming too much the story of his own life; a reflection of his own plaintive desires. Harsha wanted to burn the scrolls and start all over again. Maybe he would write something more romantic, something light and promising. But he wondered if he would ever have the time now, since his time at the university was drawing to an end.

As he had prepared to return to Nalanda for the beginning of a new term, his father had accompanied him down the palace steps. He had blessed Harsha and then held him gently by the shoulders. Harsha remembered with a swift momentary gladness that he was then almost as tall as his father, the man he had always measured himself against. Harsha’s hair, held in a loosely bound turban, fell wavy and thick against his shoulders. He had his mother’s features, a princess of Valabhi, with her expressive eyes and delicately shaped lips.

‘Your brother says you will make a fine warrior. He is keen to teach you all he knows. “With Harsha by me,” Rajya once told me,’ his father had a fond smile as he reminisced, ‘“we can become rulers no one would dare attack.”’

One more season, Harsha sighed, and then he would have to leave Nalanda to take his place as his brother’s loyal supporter. Duty mattered more, but the treacherous old doubts continued to resurface in his mind.

How did the Buddha do it? Did the Buddha not ignore his own duty?

‘These are difficult questions you ask,’ his teacher Shilabhadra had said when Harsha had placed his dilemma before him. ‘If Siddhartha had not renounced everything, he would not have found the truths he did, and we now follow willingly in his path. The Buddha taught us to be wary of attachment, how we might confuse it with duty, how much of an illusion the world can be, and the cycle of life and death.’

The Buddha fascinated Harsha. He thought he saw similarities between the Buddha’s early life and his own, but he did not have the luxury to just give everything up, he thought with bemusement, though he was the second son.

The dilemmas of duty vis-à-vis one’s calling. He sighed as he rolled his scrolls up, ran them against each other. He leant against the trunk of an old, gnarled mango tree from where he had a clear view of the amphitheatre and the steps leading to the library. He heard a swishing noise then, the sound of something fine and sharp cutting through air.

He looked around and saw the dancing figure of the monk, his sword a band of lightning, moving swiftly and gracefully in the space between the trees and the pokhara. As he moved faster, sword and man merged as one, and only the soft thudding of his feet, the flash of his white robe mingling with the silver sword blade, the flight of birds from one tree to another in alarm, indicated his presence.

When he had finished, the monk’s smile directed Harsha’s way was not one of triumph – instead he looked like someone who had emerged from long moments of meditation. ‘You must teach me what you just did,’ Harsha said, his voice still holding his amazement.

Huike extended his sword instead, gesturing at him to take his turn. The long curving blade of metal was surprisingly light. ‘You will soon see it has a mind of its own. And then you will automatically follow it. Your body will know what to do.’

Harsha watched him a few more times before he took his turn, swirling and turning with agility like he had seen the monk do, and Huike’s laugh of surprise was encouragement. That was the beginning of a friendship, one that would have to be short, destined to last only a few days.

Harsha had just been toying with the idea of travelling to Zhongguo to learn the fine art of sword fighting as in China, but one day Huike didn’t turned up for his practice sessions at the amphitheatre. Harsha learnt then that Huike had left urgently, to travel to Gauda to the south, a journey of two days by boat from Nalanda. ‘He had come here on the express wishes of the Gauda king,’ Shilabhadra explained.

And that was Shilabhadra’s dilemma too. ‘King Sasanka is far too ambitious. He has funded a lot of things here, but now wants Nalanda to accede to his wishes only. It’s his way of appearing powerful.’ The Gauda king wanted all the glory and power for himself. Shilabhadra had to accede to the wishes of those who patronized and financed his university.

As Harsha would soon find out, that his term at Nalanda would be revealing in other ways too.

There was something intriguing about the man when Harsha first saw him, the way his left eyebrow was raised in a perpetually quizzical look. They had run into each other in the corridor one evening, when Harsha was returning to his room, and the two performed a strange rhythmic dance, half-laughing, as they tried to sidestep each other. The corridor was lit by the tapers placed at every open window, and Harsha caught a glimpse of the man’s face. The smoke drifted out and the fragrance of the jasmine creeper wafted in slowly. The man had a pointed face, with a blunt nose, narrowed eyes and a quirky left eyebrow. In truth, Harsha had been somewhat distracted. That was the day he had first caught sight of the princess of Sinhala and now had only a moment’s respite before rushing to another class. His mind was also on his unfinished play. At least it had a name now: Nagananda – the prince who had resolved to become a monk, but his father made known his decision to give up kingship and renounce the world. That left the prince in a dilemma, for now he was unsure if duty willed that he assume the throne his father had given up. It was a test the prince was not willing to take on. Harsha was still stuck on that note.

If he thought the matter through, he was sure he would find a way, for a play was much like life itself. The more one contemplated, the more life seemed easy to understand. He did not know yet that such deep thoughts were little more than youthful fantasies and wishful thinking.

His first glimpse of the princess had come about rather unexpectedly. He had been sitting under the banyan tree, lost in thought, his palm scripts scattered around him, when he heard the singing. Looking up he saw the women at the pokhara, their anklets ringing against the stone steps, and he realized that the royal entourage from Sinhala, led by its princess, had just arrived. The entourage had already been to Gaya, to pray at the monastery set up more than 300 years ago. Harsha drew in his breath as he looked on, unobserved. He knew all the rumours he had heard thus far were true, for he had never seen anyone so beautiful as the Sinhala princess. She laughed gaily as she led her attendants into the water, a sound that drowned everything else. Harsha got to his feet awkwardly, his scripts gathered up untidily as he tried to make a quick getaway. He did manage to steal another quick look at the princess, with her long black hair now wet and clinging to her back, her skin glowing in the soft sunlight and her dark eyes flashing with laughter at something her companion said.

The next morning, however, he was at the gate of the guesthouse where the entourage was lodged. ‘The princess does not wish to be disturbed,’ said her attendant, looking down at him from the balcony, kindly, while the guard, one of her own people, short and stout and profusely sweating, had been equally contrite: ‘The princess is aware that you’re the prince of Sthaniswara. However, you are the son of a proud Shaivite warrior, and your brother is a devotee too.’

‘But I am not one,’ he had demurred. Was a man fated never to leave the shadow of his family?

The guard was sympathetic. ‘Ultimately, you will follow your family’s diktats, O prince. The princess sees your interest in the Holy One as superficial. And our princess is dedicated to the Buddha.’

Harsha wasn’t one to let things be. The next day, he inveigled to run into the princess’s path when she was on her way to the pokhara. Her friends and attendants were a little way behind, and he came up suddenly, startling her. His smile faltered at the angry accosting looks of all the women, as Princess Ratnavali looked him up and down, quite in a regal way as befitting a princess, even one who had nun-like ambitions. She did not slow down, knowing he would keep up, and her first words told him that she too knew a bit about him. ‘Anusuya tells me you are the prince who wants to write plays like Kalidasa. I am sorry I was at my prayers when you called earlier, and so they had to tell you to leave.’

‘I am not so ambitious,’ Harsha protested mildly. ‘And you’re a princess who knows so much about the Buddha. I thought perhaps you could help me.’ He told her about the play then, improvising as he spoke, ending at the part where the prince was faced with a difficult choice. It struck him then that love could offer a solution – the prince of his play meeting a princess who would be a companion in every way.

The princess smiled. ‘Maybe my friends and I can help you get over it.’

He flushed, knowing that she had guessed his intentions and that it amused her. He walked away, aware that the women were already exchanging glances full of meaning, holding on to their giggles till he was well out of hearing. It was as he made his way back to his room, lost in thought, that he thought he saw the stranger again, the man whose path had crossed his the evening before, but now he couldn’t be sure. But the image of the man with the raised left eyebrow returned, and Harsha felt his instincts were trying to tell him something.

Late that afternoon, he was by the Ganga, bathing and playing with the elephants. The boys in the stables were playing too, diving into the water in a challenge to each other. The waves they threw up splashed over the elephants, making them trumpet in equal joy. The splashing everywhere, the rise and fall of the water in waves, the boisterous trumpeting elephants, the laughter of the boys, all made things pleasantly blurry around them, and when Harsha turned, he saw a horseman race out of the stables. That gave him cause to pause. It wasn’t often that a monk rode with such urgency and assurance. The thought returned to him moments later, when he looked towards the western skies. It wasn’t the screams so much as the thin plumes of smoke that alerted him. In an instant, everyone by the river was looking up at the fire. It was right where his room was, and the wing where most guests too were put up.

Harsha rushed out without a thought, his wet clothes clinging to his body. He ran past the stables, the garden, the pond and the big kitchens, seeing the smoke gush through the windows, a plume of orange rising in the sky. A grey haze soon enveloped the smooth red walls in his line of vision.

The other monks were already there, and he ran up the stairs behind them, pulling up two slender-necked earthen urns which were always filled with water and placed outside every monk’s quarters. The fire raged across several rooms, including his own; the thin wooden frames of the windows fluttered, some breaking off, and the smoke heaved and billowed out, thickening with every moment. Harsha was certain he had not left a taper on, burning carelessly.

Covering his mouth with his soft upper robe, his eyes tearing up in the smoke, Harsha broke his door open. The flames leapt at him from a corner, and a quick glance confirmed what Harsha suspected by now: the fire had begun from somewhere near his bed, where a taper had fallen over on the coir mattress. If he had been sleeping, taking an afternoon nap, he could have been killed or burnt very badly. He joined three other monks as they splashed water with some determination, urns passed on by others just behind, and they used their upper robes to swat at the flames and embers. Harsha reached for his blanket to thump the fire out, stamping on it ruthlessly. By the time they had the fire squelched, his hands were blackened, fingers singed in places, but he was glad his scrolls hadn’t been completely destroyed.

Later that evening, the acharya Shilabhadra summoned him. The fragrance of the incense burning in his chamber was heady and comforting. It erased every trace of the fire, the smell of ash and burning leaves left on him. Shilabhadra examined his injuries, that had been treated with turmeric and basil, and then came to the matter on hand. ‘Your father has become more insistent,’ he said, abruptly. There had been messages that the acharya had kept to himself but now Harsha had to go – the acharya thought the fire was an omen.

He would hear no argument to the contrary, so Harsha kept his thoughts to himself. It seemed to him now that the fire had not been an accident. The stranger he had seen earlier had not been spotted since. Harsha was certain he was the one who had ridden away on a horse, soon after committing his crime. Had he really been a monk?

Harsha set off for Sthaniswara, sailing up the Ganga. His mind was on too many things: on Nalanda, the people old and the very new – the stranger whom he now suspected of arson, and the princess of Sinhala. He had had no time for farewells, and he hoped Princess Ratnavali would think of him, at least with some surprise at his sudden departure. He knew too that his brother was somewhere in the far north-west, in the region of Gandhara, where some stray Huna groups were rumoured to have made incursions. A wall needed to be built, his father had said, and Rajya had insisted he would go in place of his father.

There had been peace in the northern kingdoms for about a generation now. The days when the great Huna warlord, Mihirakula, had been defeated first by the brave Malava king, Yashodharman, and then the Gupta ruler, Narasimhagupta, were still talked about in legend and song. A century later, the Hunas had been greatly weakened, thanks to his father’s efforts, but they could never let down their guard. Two ayanas ago, still a student at Nalanda, Harsha had once followed his father to the north, and had been impressed by what he had seen in Taksashila. Seeing the remains of an old university there had fired his ambition to be a scholar.

The Ganga now flowed serene and untroubled. Harsha’s boat was well equipped, and another one followed with servants and provisions for food. Every morning, as they set off again after a night spent anchored on shore, the mountains to the east shimmered, appearing closer every day than before.

They were somewhere close to Kanyakhubja when the messengers from Sthaniswara found him. The boat drifted up from the north towards dawn. Harsha understood his father was just ensuring he reached safe and remained undistracted. This concern on his father’s part bemused Harsha no end. It is as if my father senses my conflicted heart, torn between duty and desire, or, Harsha thought as he turned to the monk with him, he suspects I have company he wouldn’t quite approve of.

Prathama the monk, who was with him, and who would go up north-east from Prayaag, was lost in thought. He had sneaked a ride in the boat. Harsha knew his father would have grudgingly condoned this, knowing that roads could be infested by robbers; monks and other travellers hence preferred to travel in safe company. But Prabhakaravardhana always believed that it was a monk at Taksashila who had first influenced his son and filled his head with ‘silly ideas’. There had been an argument before his mother, Yashomati, had intervened. His father had been more indulgent then.

‘You were born to be a warrior and need to be one. There will be many things to tempt you, son,’ his father often said in the insistent tone Harsha remembered. He had kept quiet and later had confided in his sister, Rajyashri. ‘Must I be a warrior just because I was born a warrior king’s son? Even the Buddha as Siddhartha was born into a kshatriya family.’

‘I think,’ Rajyashri had replied with a wry smile, ‘that decision disappointed his father immensely. You know the Shakyas ruled over a small republic; Suddhodana wanted his son to succeed him, but the other chiefs must have been secretly happy.’

‘There was no peace in Kapilavastu, then?’ he had asked.

He wished he had had more time to talk to his sister, but she had wanted him to help her instead, to reach out to Grihavarman, the young Maukhari king she had set her heart on marrying.

Harsha stopped at Kanyakhubja, from where it would take him three days by boat to Sthaniswara. He was ceremonially welcomed by Grihavarman, a young man with blazing eyes and a shy smile, who had stood by the riverbank waiting for the boats to draw slowly in. Together, they had watched the drummers perform till late in the night. The next day, Harsha saw the Maukhari boat that was now part of his entourage. It was loaded with vats of fragrant rice and ghee, specially carved ivory shields and horns, and in Harsha’s own belongings, there was a scroll he had to pass on to his sister: a message from Grihavarman.

‘I hope the Sthaniswara princess will see this message soon,’ Grihavarman said, a faint blush staining his cheeks, as the two men said their farewells on the ghat steps. ‘I do promise that, O king,’ Harsha replied, smiling. ‘I am sure she will greet me more effusively because of this.’

He felt his heart lighten as he anticipated his sister’s joy. A day later, once he felt the cold winds on the north on his face, he knew he was glad to be headed homeward.

1

Suitors for a Princess

Sthaniswara looked its best as winter ebbed. The rains had eased, and preparations for the princess’s swayamvar were at an advanced stage. Harsha had penned the invites himself in the script that everyone admired. Even Bana, who was considered the most talented in the world after Kalidasa, agreed. Harsha dipped his pen in the inkpot and wrote things out painstakingly.

The invitations had gone out to every king in the land, even those who ruled places far south and east. Together, Harsha and Bana had penned verses, one for every eligible suitor, listing their many enviable qualities, showering fulsome and, most times, exaggerated praise.

But Harsha knew the truth as to whom his sister preferred: the handsome Grihavarman who ruled over Kanyakhubja. There had been disagreements over Rajyashri’s choice. Rajyavardhana had sided with his parents, and the brothers had been thus divided. Griha had tried his bit too to win over Rajyavardhana by volunteering to lead a small Maukhari force under Rajyavardhana’s command against the Hunas.

A royal marriage had to serve interests of strategy, and alliances between kingdoms helped to fight off a bigger enemy. Only a hundred years ago, the great Gupta king Chandragupta had fought off the Sakas. Then had come the terrible Hunas, led by the bloodthirsty Mihirakula. They had descended from the northern plains and destroyed the monastery at Kaushambi. The Malava king Yashodharman and the Gupta king Narasimhagupta had finally allied and defeated the dreaded Mihirakula. The Hunas were still hated; coins of Mihirakula were stamped upon and spat on. As those memories had been passed down, the fear of the Hunas had only endured.

Harsha’s parents wanted Rajyashri to marry Devagupta of Malava, a kingdom that was at the heart of Bharatvarsha. The marriage would help form a formidable alliance, dissuading any potential invader. The Hunas remained a threat always. Rajyavardhana already spent too much time on the frontier, which worried their mother, Queen Yashomati, terribly.

Harsha knew an alliance between Malava and Sthaniswara, the centre of Pushyabhuti power, made sense, but he also knew his sister’s desire. She and Griha had been exchanging letters since the time a wandering bard had brought in stories about the Maukhari king – that he had once crossed into the high northern mountains and, as legend had it, encountered a giant creature who looked halfway between a bear and man and dwelled in the caves. The king had described the world below in the plains to the creature in such wondrous words that he hadn’t been taken prisoner. In return, Griha had promised the creature that he would never be disturbed, that the trade and pilgrim caravans would henceforth take a different route northward.

Harsha knew of these letters. He liked Grihavarman, a practical man not given to much exaggeration. He was strong and tall, with a thin moustache, his eyes always holding a smile. At their last meeting, Griha had indeed spoken of his journeys towards the Shivaliks, to the land of Bhotan, but had not said anything about meeting giant monsters. Instead he had mentioned emaciated ascetics, monks so ethereal they could have been gandharvas. Then he had described the snow leopards, elusive creatures whose mere sighting could prove auspicious.

Rajyashri’s friend, Chitralekha, had then drawn pictures of him for the princess. She had relied on what the bard had described. Rajyashri had been charmed by the bard’s descriptions and the letters she had received in turn from Griha. The Maukhari king too had been smitten when he had received, in turn, a portrait of Rajyashri.

But a marriage was at best a political decision; it had always been so. Alliances between kingdoms made them stronger. Forces could then be combined to fight a common enemy, as had happened when the Gupta princess Mahasenagupta had been married to Srivardhana, the first great king of Sthaniswara and Prabhakaravardhana’s father. The Gupta forces had aided the northern kingdom of Sthaniswara in holding back a second wave of Huna invasions, which had come on the heels of Mihirakula’s death. But Rajyashri took exception to this. Kanyakhubja, she pointed out, was just as important as Malava. She had a clear favourite in this matter, and would not be a pawn to serve the kingdom’s political interests. She had even stopped speaking to Rajyavardhana since he took their father’s side on the matter.

Then there were the kingdoms that had actually put out feelers seeking Rajyashri’s hand. Sthaniswara, ruled by the Pushyabhutis, was a rich and fertile kingdom. It was located right where the rivers Ravi, Chenab and Sutlej flowed through, and close to where the traders came from the north-west.

In the end it had been decided that a swayamvar would be convened. It seemed like a good idea to assemble all the important kings of Bharatvarsha. Bharatvarsha was a land with a unique identity of its own. The Himalayas made up the land’s northern wall, protective and all-encompassing, and its peaks hidden places where the gods lived and guarded the land. Legends of Bharatvarsha’s brave kings spread far and wide; every prince looked up to these kings of the epics and hoped to emulate them.

Harsha was in charge of overseeing every arrangement for the royal suitors. He knew he had the responsibility of showing Sthaniswara in all its glory; it gave him a chance to build relationships and alliances anew with princes and kings and chiefs across Bharatvarsha. His brother, Rajyavardhana, would ensure the borders to the north were safe, and that all was as it should be at the guard posts and watchtowers. No celebration could come in the way of keeping the people safe and happy. His father seemed pleased, and justly proud of his sons. Their capabilities complement each other’s, he thought.

Harsha found all this challenging and new. What gave him special excitement was discussing every detail of the guests with his friend Bana. He delighted in the information he gathered and enjoyed the gossip. In the evenings, he met with his father and other officials. Often there would be a messenger from his brother. The farther Rajyavardhana rode along the rivers to the north, following Sakala and the other cities beyond it northward, the longer the messengers took. The Hunas were still cautious. They had not advanced and such news could only be good for Sthaniswara. It was reassuring that the Hunas had been contained by the stinging defeat given them by Prabhakaravardhana some ayanas ago.

That was the first time Rajyavardhana had accompanied their father, and Harsha had loved listening to the stories – how the monks had helped them find the secret routes and trails, and the negotiations that had followed the first battle, when the Hunas had lost. They had had to surrender several cattle herds and make promises of peace as a compensation. But as King Prabhakaravardhana said, a kingdom should never let down its guard, within and without. And now he was glad he had his two sons as support.

Among those who had sent out feelers was King Sasanka of Gauda, the eastern kingdom. He was known to be a fierce warrior, and a worshipper of the fiery, ever-angry Shakti. It was known that he worshipped Goddess Chamunda and smeared his forehead with the blood of a goat. There were also rumours that of late he had become an ardent worshipper of the snake goddess, Manasa. Gauda was a rich province, its ships sailing into the seas as far as Kambhoja in the east and even sailing up the Ganga to Kanyakhubja and beyond. He kept all these kings in good humour, including the Magadha king and the Maukharis as well.

But King Prabhakaravardhana was wise enough. He knew Sasanka was ambitious and manipulative and was only planning to enforce his own authority over the areas north of Gauda by citing his relationship with the Pushyabhutis.

‘While your brother deals with the Hunas with his valour, you too must battle Sasanka, with your wits,’ Prabhakaravardhana told Harsha while putting away the scroll he had just received. ‘For he is a cunning man, with all the guile and complexity of the men of the east.’

His father talked of the time Sasanka had been furious when Prabhakaravardhana had turned down his offer of alliance. ‘He believed,’ his father recalled, ‘that between us, we could have divided the whole of Bharatvarsha, the river Godavari being the border.’ Just as he had resisted on that occasion, this time too Prabhakaravardhana tactfully resisted his offer of marriage: Sasanka would be a special guest at the swayamvar but Princess Rajyashri would decide for herself.

Harsha had already heard much about Sasanka of Gauda at Nalanda and knew what he looked like. Now the messengers described him too, and Chitralekha came up with yet another portrait. Sasanka wore his hair in a topknot, he had beady eyes, a square jaw, and a terrible fondness for gold. He preferred long dangling earrings, and usually a heavy gold necklace sat full on his chest.

Sasanka had accepted the invitation forthwith. He detailed in his message that he would travel up to Sthaniswara in a fleet of boats, with his posse of soldiers. Their horses and his elephant would travel in the elongated boats he was so proud of. Harsha knew this meant a huge compound would have to be set aside close to the river for the horses and Sasanka’s elephant. Sasanka insisted that protocol and custom dictate this impressive entourage. They would come in peace, his message assured, almost mockingly. Prabhakaravardhana had a strategy in place as well. Sasanka’s entourage would be escorted by soldiers, his own and the Pushyabhuti soldiers too, riding in tandem, carrying the flags aloft – the tiger for the Gauda kingdom, and the stork flying high for the Pushyabhutis. The bird was a symbol of their ambition, one tempered with gentleness.

Buddharaja of the Kalachuris ruled over a kingdom to the south of Malava. He was considerably older

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...