- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

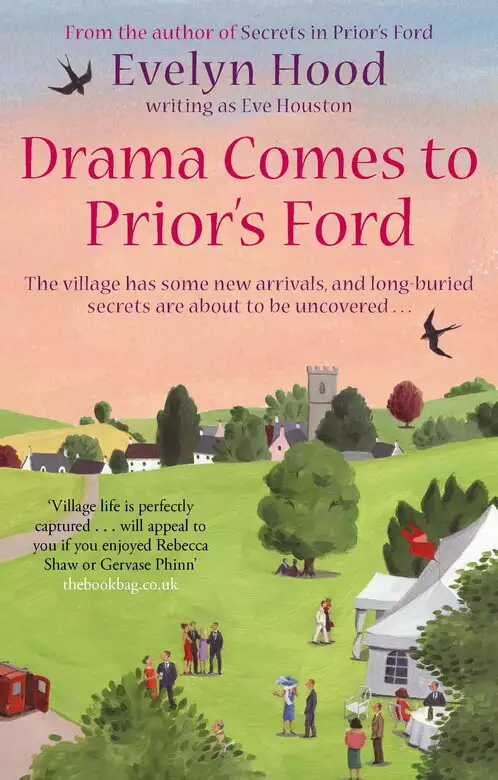

Synopsis

The residents of Prior's Ford are facing more upheaval . . . There are new arrivals at Prior's Ford - Meredith and Genevieve Whitelaw - who are determined to shake things up. Meanwhile, Alastair Marshall finds he is missing Clarissa Ramsay, now travelling the world to recover from the shock of her husband's affair, more than he would like to admit. At Tarbethill Farm, the McNair family is struggling to make ends meet, and face the prospect of losing the livelihood that has been in their family for generations. And Jenny Forsyth is to be reunited with her step-daughter Maggie - but Maggie is now a precocious teenager very unhappy at the idea of country life, and determined to cause trouble . . .

Release date: March 7, 2013

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Drama Comes To Prior's Ford

Eve Houston

An hour or so later, having delivered post in the neat little village and to the cottages and farms further afield, the van headed back towards its depot, leaving behind a paper trail of letters bearing good tidings for some, bad tidings for others, and a heartfelt plea that was to change one family’s comfortable existence for ever.

In the village store-cum-Post Office, Sam Brennan turned his back on the shoppers browsing along shelves and pulled off the elastic band holding the day’s post together. He skimmed swiftly through the bundle, finding only bills and junk mail, but no envelope with his name written on it in a familiar hand.

Almost three months had passed since Marcy Copleton had walked out on him and still there was no word of where she was, how she was, when she was coming back – if she was coming back.

He went through the post again, hoping against hope that the letter he sought might have got caught up in something else and been bypassed. But again, the search was fruitless.

‘Morning, Sam!’ a cheerful voice called, and he tried to pin a smile on his face as he turned back to where a customer waited, a full wire basket slung over her arm.

Perhaps tomorrow, he thought as he unpacked the basket and pressed keys on the till. Until then, he was faced with another day of waiting.

Another twenty-four hours.

In his isolated farm cottage, Alastair Marshall abandoned the half-finished painting on the easel as soon as the single letter came through the letter box. Wiping paint from his hands he opened the envelope and began to read.

Dear Alastair, Clarissa Ramsay had written. Here I am, in Honolulu on the first lap of my year’s adventure. It has been wonderful so far – the cruise from San Francisco was perfect and everyone on board ship so friendly. Next stop West Samoa. It is hard to believe that if I was still in Prior’s Ford I would be enduring winter weather …

A photograph slipped from between the pages and fell to the floor. Alastair picked it up and looked down at the smiling middle-aged woman, wearing a blue summer dress, and standing before a mass of flowering bushes.

The young artist ran the tip of a finger over the happy face. The first time he had laid eyes on this woman, almost exactly a year before, she had been grey and haggard, steeped in despair and unhappiness. Now, her eyes sparkled and her skin glowed; now she was beautiful, and she didn’t look much older than his own thirty-four years.

He laid the photograph and letter down and reached for the sketchbook never far from his hand. Normally he painted landscapes to be sold, if he was lucky, to summer tourists, but now he began to sketch the woman in the photograph.

At Tarbethill Farm, Jess McNair had poured her morning mug of tea and was filling three more mugs, larger than hers, when her husband Bert and their two sons arrived, the dogs hot on their heels and eager to get to the Aga’s warmth.

‘Idle buggers,’ their master growled at them, and both collies, mother and son, flattened their ears and slid apologetic glances at him from the corners of narrowed eyes before subsiding gratefully on to the old rug that had covered the flagged floor for as long as anyone could remember. Jess’s mother-in-law had made the rug when she was a young bride; it had had a pattern then, but nobody remembered now what it had looked like.

As the farm dogs nosed in beside him, Old Saul struggled to his feet slowly and painfully in order to give his master’s reddened lumpy hand a swift lick. He had been born on the farm when Bert was a comparatively young man; now, they were both slow-moving and rheumaticky. Old Saul had the best of it – he was retired and spent most of his days by the Aga while Bert struggled on with help from Jess and their sons, Victor and Ewan.

‘Somethin’ smells good, Ma,’ Ewan said now, rubbing chilled hands together and sniffing the warm air.

‘Pancakes.’ It was generally agreed by the women of Prior’s Ford that nobody could make pancakes like Jess McNair.

‘Mind an’ put plenty butter on ’em.’

‘Don’t you read the papers, Dad?’ Ewan asked, winking at his older brother as Jess began to lather butter on the still-warm pancakes. ‘Butter’s bad for you. Gives you cholesterol and all sorts.’

‘Get away with ye – I’ve eaten it all my life an’ I’ll eat it till the day I die.’ Bert tugged his old cap, put on every morning when he got dressed and kept on until he undressed again at bedtime, more securely over his thinning grey hair. He pulled out one of the chairs set round the scrubbed kitchen table and dropped into it, picking up his mug, to which Jess had already added milk and sugar, just as he liked it.

‘Post’s in.’

‘Haven’t you opened it yet?’

‘I opened a letter from our Alice; she’s doin’ fine, but the rest’s for you.’

‘I thought women were supposed to be nosy.’

‘If you got hand-written letters smellin’ of perfume, Bert McNair, I’d open them, but I’m not bothered with the other sort. They’re on the dresser, d’you want them over?’

‘I do not, for it’ll only be beggin’ letters and bad news. It can wait.’

Even in wintertime there are things to be done on a farm, and as soon as they had downed their tea and had three pancakes apiece, Victor and Ewan went back to work while Bert picked up the post and began to rip envelopes open with a yellowing thumbnail.

‘Bills, bills an’ bloody bills,’ he said gruffly.

‘Is the cheque for the milk not due today?’ Jess asked. Like her husband, she was weathered from an outdoor life, and her hair, too, was grey and beginning to thin. ‘It’s usually in by this time.’

‘Aye, it’s here.’ Bert took it from its envelope. ‘But for all there is, it might as well not be. Puttin’ that into the bank’s like throwin’ a pebble in the river. I’d like to hear what the bloody supermarket owners’d say if it cost them more to provide their produce than they were paid for it.’ He wrenched at his cap, pulling it down almost to the bridge of his nose. ‘We can’t go on like this, Jess.’

‘We’ll weather the winter. We always have.’

‘Aye, but it gets harder every year. Brussels an’ our own governments an’ the supermarkets between em’s dug a mass grave for farmers. I reckon they’ve just about tipped us into it now. We’re goin’ to have to talk things over with the lads before the soil starts bein’ shovelled in on top of us.’

Bert stamped to the outer door, opened it and roared, ‘Out!’ with such ferocity that the dogs leapt to their feet and bolted past him and into the yard. Even Old Saul woke from his doze with a start, his head and legs flailing in a vain try at jumping to attention before he gave up and dropped back to the rug.

When Bert had gone, slamming the sturdy wooden door behind him, Jess watched from the window as he strode off across the yard. His eyes were on the ground and his head almost lost between shoulders that had once been straight and broad, but were now bowed.

Once he had rounded the byre and disappeared from sight she went to the table and picked up the envelopes, going through them one by one. Bert was right – the bills outweighed the single cheque; it was happening too often. They couldn’t go on like this.

Old Saul whimpered slightly and she went to him, bending to run a hand over his side. ‘Settle yourself, lad, you’ve done your bit,’ she said, and his tail flopped against the rug in gratitude.

Jess went back to the window and looked out at the farmyard. The sky was low and heavy and the cold wind fluttered the feathers of the few hens pecking among the cobbles.

She suddenly shivered, as if the wind had managed to find its way inside and was blowing through her snug, safe kitchen.

Jenny Forsyth and Helen Campbell got off the afternoon bus in Main Street, each loaded down with Christmas shopping. As they turned down River Lane, Helen talked about her plans for the latest chapter in her novel. Helen’s big ambition was to become a writer, and for more than a year she had been taking a postal writers’ course. She had recently sold her first short story to a woman’s magazine, but her plans for fiction writing had been put on hold when the abandoned granite quarry near to the village was almost reopened.

Against her will, Helen had become the secretary of the local protest committee, a job that led to a meeting with one of the reporters on the Dumfries News, a weekly local newspaper.

When plans for the quarry were dropped she had been asked to write a weekly column on the happenings in Prior’s Ford. The good thing was that it brought in some much-needed money. The drawback was that it got in the way of the novel writing.

‘Come in for a cup of tea,’ Jenny offered as they came to the parting of the ways.

‘The children’ll be home from school in half an hour,’ Helen said doubtfully; then, succumbing to temptation, ‘but I’ll just pop home and hide these things while you put the kettle on.’

Helen hurried off to the left, into Slaemuir council estate, while Jenny turned right into the more affluent Mill Walk estate. Once Jenny had put her own shopping away and switched the kettle on she collected the post from the doormat. Two letters addressed to her husband Andrew were placed on the telephone table while she opened the single letter addressed to her personally.

When Helen arrived a few moments later, a radiant Jenny whisked her into the house. ‘You’ll never guess what’s happened!’

‘You’ve won the Lottery?’

‘Better than that!’

‘There is nothing better than that,’ said Helen, who had four children to feed and a husband on a low wage.

‘There is!’ Jenny waved a letter at her friend. ‘Maggie’s coming to live with us!’

‘Maggie? Are you talking about your wee step-daughter?’

Jenny nodded, her eyes suddenly filling with tears of joy. Her first husband had been a bully, and the only happiness Jenny had known during their brief marriage came from Neil’s small daughter from his first marriage. She had finally run away from Neil, but had never stopped missing Maggie. A few months earlier, Neil’s brother Malcolm had discovered where she lived, and Jenny had heard from him that Neil was dead, and Maggie living with his parents.

‘Malcolm’s written to say that his father’s ill and his mother can’t look after Maggie as well as him, so they want us to take her. Oh, Helen – I’m getting Maggie back – for good this time!’ Then, suddenly remembering why Helen was there, ‘Come into the kitchen, it won’t take a minute to make the tea.’

‘Jenny—’ Helen followed her into the spacious kitchen, ‘Maggie’s not the wee girl you knew. She’s about twelve now, isn’t she?’

‘Fourteen. It’ll be great to have a daughter! We can go shopping together, and— Oh, it’ll be lovely!’

‘You’ll have to talk this over with Andrew.’

Jenny spooned loose tealeaves into the teapot and added boiling water. ‘He’ll be thrilled.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘Of course I am – he knows how bad I felt at having to leave her. She was such a sweet little girl.’

‘She’s not a little girl any more.’

Jenny was setting mugs out on the kitchen counter. ‘We’re the only people who can take Maggie. Malcolm’s wife has multiple sclerosis, and without us to take her she might have had to go into care.’

‘What about Calum? You have to think of him as well.’

‘But it’ll be so good for him. We were never happy about him being an only child, but we just didn’t get lucky again.’ She poured tea into the mugs. ‘Now, he’s going to have a sister!’

‘Who’s going to have a sister?’ Calum asked from the kitchen doorway, and both women jumped.

‘That’s not the school out already, is it?’ Helen asked.

‘Yes, that’s why I’m home,’ nine-year-old Calum explained patiently. ‘Mum, who’s—?’

‘That means the children are home and I’m not there. Jenny, I have to rush.’

‘Your tea!’

‘Must go – talk to Andrew,’ Helen said, and fled.

As Helen crossed River Lane and ran towards her own house the school bus bringing the older Prior’s Ford children home from Kirkcudbright Academy stopped outside the village store. Its uniformed passengers flowed off, some of them lingering on the pavement.

‘Wow!’ Jimmy McDonald said, and they all turned to look at the long, sleek car coming along Main Street. A young woman was at the wheel with an older woman, beautifully dressed and immaculately groomed, in the passenger seat.

As the car passed the teenagers Steph McDonald stepped forward, beaming, and stooped down to wave in at the passenger window. The older woman turned, smiled at her, and lifted a gloved hand in an elegant salute.

‘Who’s that, Steph?’ Freya MacKenzie asked.

‘Oh, its Mrs … it’s … you know her!’

‘No I don’t.’

‘Did you see the way she waved? Just like the Queen.’ Jimmy sniggered.

Steph was knitting her brows, trying to think of the woman’s name. ‘She’s— Oh, we’ve all seen her around the village!’

‘Not in that car,’ Jimmy said, while Ethan Baptiste, the Jamaican godson of local minister Naomi Hennessey, herself part-Jamaican, added, ‘I’d know if I’d ever seen that car around here. Right, Jimmy?’

‘Right on, Ethan.’

They began to straggle off to their homes, Steph still racking her brains, while the car turned into Adams Crescent and stopped at the first house, a pretty two-storey detached villa set in a neat garden.

The driver, a dark-haired girl, got out and went round to open her passenger’s door. The woman who had caught Steph’s attention emerged gracefully from the car, smoothing down her pearl grey, fur-collared coat, and surveyed the house carefully.

‘Willow Cottage,’ she said in the husky voice known to millions of avid television soap fans. ‘A pretty name, don’t you think, Genevieve?’

‘It’s as good as any.’

‘I just hope that this Mrs Ramsay has got taste. I couldn’t bear to live in a house that has no taste, even though it’s only for a short while.’

‘You saw the photographs, Mother. It’s fine.’

Meredith Whitelaw shot her daughter a pained look. ‘Genevieve, how often do I have to tell you to call me Meredith?’

‘And how often do I have to ask you to call me Ginny?’

‘You’re too old to call anyone “Mother”!’

‘I hate Genevieve. Do I look like a Genevieve?’

Meredith eyed her daughter’s cropped hair, only just framing a square face with not a spot of make-up on it.

‘You were a beautiful baby – how was I to know that you were going to take after your father?’Then as a bloodcurdling yowl came from the back seat she opened the rear door and brought out a cat basket.

‘Gielgud, my poor darling! Poor liddle pussums. Did Mummy forget you, den?’

A pair of furious blue eyes glared at her through a space in the basket and the Siamese began a steady low grumble. ‘Just one more minute, sweetie, and you’ll be out of that nasty nasty basket – promise!’

As Ginny hauled cases and bags from the car’s roomy boot, Meredith turned to survey the village green and, beyond it, the sleepy Main Street. Above the shop roofs, rounded hills could be glimpsed, their tops wreathed in cloud.

‘Sweetie,’ she said to the cat rather than to her daughter. ‘I rather believe that we’re going to enjoy living in this pretty little backwater. Though methinks that we just might have to spice things up a little …’

‘Who’s going to have a sister?’ Calum Forsyth asked his mother again as the front door closed behind Helen.

‘You are – isn’t it exciting?’

‘Oh no!’ He dropped his schoolbag on the kitchen floor and glared at Jenny. ‘Fred Stacey in my class has had a terrible time – his mum and dad promised him a new brother to play with and he had to wait for ages before it happened. And it’s still not big enough to play with. Fred says that it was a right swizz!’

‘I’m not talking about a baby, I’m talking about a big sister. Her name’s Maggie, and she’s fourteen.’

Calum gave his mother a long, level look, then went to the refrigerator to fetch the jug of orange juice. ‘If she’s that old, where has she been until now?’ he asked, still suspicious. ‘Why hasn’t she been here, with us?’

Jenny brought a glass from the dresser and put it on the table, then sat down and picked up her tea.

‘Well, she’s not exactly your sister, just a sort of sister. I looked after her when she was a little girl, before you were born, and I really liked her. Then I met Dad and we came here, and you came along, and I didn’t see Maggie again.’

Calum filled his glass carefully, and then carried the jug back to the refrigerator before asking, ‘So who’s been looking after her while you’ve been here with us?’

‘Her grandparents, because her mother had died and her father had to work far away. But now her grandparents aren’t well, so Maggie’s coming to stay with us instead. As your big sister.’

‘She’s a girl.’

‘Girls are all right. Look at Ella – you play with her all the time, don’t you?’ Ella MacKenzie, the younger daughter of Jenny’s close friend Ingrid, was a tomboy, and mad about football.

‘Ella’s OK. D’you think that this Maggie might be like her?’

‘Probably.’ Jenny put aside her own dreams of a girl to go shopping with, and concentrated on painting a picture of the sort of sister her son would accept.

‘Well, that would be all right,’ he acknowledged, and took a huge gulp of juice. Then, picking up a biscuit from the plate she had put out for herself and Helen, said, ‘When’s she coming?’

‘I don’t know, but soon. I’ll have to get the spare room made up for her.’ Jenny’s excitement began to build again. Ever since meeting Andrew and bringing Calum into the world her life had been perfect, but there had always been a dark shadow in the corner of her mind. She felt like a jigsaw that was finished apart from one piece – Maggie. Once they were reunited, her life would really be complete. She longed to phone Andrew, but she knew that he was having a busy day, so she would have to wait for him to get home.

When at last he came in the front door, it was Calum who reached him first. He had either had time to get used to the idea of having an older sibling, or he may simply have been influenced by his mother’s excitement; whatever the reason, he rushed along the hall and threw himself at his father, yelling, ‘I’m going to get a sister!’

‘What?’ Andrew Forsyth had had a hectic day and, between busy traffic and road works, a frustratingly slow drive home. All he was thinking of as he let himself into the house was a drink, dinner and a lazy evening in front of the television set. Now he hurried towards the kitchen, meeting his wife on her way to the hall.

‘What?’ he said again, and then, delight dawning in his eyes, ‘Jenny, does this mean that you’re—’

‘Calum, could you get the flowery salad bowl from the dining-room sideboard?’ Jenny asked, and then hurriedly, as Calum scampered off, ‘No, it’s not that, it’s Maggie. She’s coming to live with us.’

‘What?’ It struck Andrew Forsyth, even as the word exploded for the third time from his lips, that he was going to have to stop repeating himself.

‘Leave it until we’re on our own. I’ll explain everything later,’ Jenny hissed at him as Calum returned with the salad bowl.

‘I think I’ll just go upstairs and wash my hands,’ Andrew said, and took refuge in the bathroom.

The McDonald family lived in a three-bedroomed house on the Slaemuir council estate behind Prior’s Ford primary school. As their brood grew in number, Jinty and Tom McDonald had moved into the smallest bedroom, not much more than a box room, while the girls, sixteen-year-old Steph, Merle, aged twelve, Heather, ten, and Faith, the youngest at six years old, shared one room and the boys – Steph’s twin Grant, fourteen-year-old Jimmy and Norrie, aged eight, shared the other. When the entire family was at home the square living room could scarcely hold all of them.

Tonight, Tom, who had been persuaded to take on the job of stage manager for the Prior’s Ford Drama Group, had gone to the village hall to work on scenery for the annual pantomime, Grant was out with his mates, and Jimmy, a keen gardener, had bagged his absent father’s armchair and was studying a gardening catalogue that had come through the letter box that morning. Merle, Heather, Faith and Norrie were doing their homework at the table while Steph, who was supposed to be supervising them, mouthed silently over the script spread out before her. She loved acting and had won the part of the principal boy in the pantomime.

For once, the house was peaceful and Jinty took advantage of the lull to relax in an armchair, teacup in hand as she watched a soap opera on television. She was addicted to soaps; she felt as though she knew all the characters, and it cheered and comforted her to see that their lives could be just as hard as hers. Jinty loved her large brood and adored her still-handsome husband Tom, a joiner by trade. Since Tom spent a lot of his free time in the Neurotic Cuckoo and was an unsuccessful gambler, Jinty was frequently the family’s main wage earner. In the summer she worked at Linn Hall, the largest house in the village, and she was also a cleaner at the pub, the village hall, the primary school and the church, as well as charring for one or two of the career women living in the Mill Walk housing estate.

There were those who thought that Jinty, born and raised in Prior’s Ford, and a much-liked member of the community, deserved a better husband, but she wouldn’t have exchanged him for the richest man in the world. Tom’s waistline, like hers, had spread and his thick auburn hair was well seeded with silver, but even so he still had more than a passing resemblance to the handsome young man who had swept her off her feet almost twenty years earlier, the man she still saw every time she looked at him.

Now, without taking her eyes from the television screen, she held out her cup. ‘Pour us some more tea, will you, Heather?’ she asked, and Heather laid down her pen and left her seat, glad of the chance to take a break.

She splashed tea into her mother’s cup, added some milk, then leaned on the back of Jinty’s chair to watch the drama unfolding itself on the flickering screen. ‘Why’s that man crying?’

‘His mother’s just been badly hurt in an accident.’ Jinty took a sip of tea. ‘They don’t think she’s going to survive. Surely they’re not going to let her die – I can’t imagine Bridlington Close going on without Imogen Goldberg. She’s the leader of the pack, that one. See, there she is.’

The scene had changed to a bedroom, the camera zooming in on a woman lying in bed, propped up on a pile of pillows. Her short white hair was immaculate, her face perfectly made up, but her voice, as she spoke to the people clustered about the bed, was weak.

‘I think she’s going. Oh, poor Imogen,’ Jinty mourned as Steph, suddenly realising that one of her charges was missing, turned round.

‘Heather, you’re supposed to be doing your homework!’

‘I’m coming – just let me see what happens first.’

Steph cast an irritated glance at the television screen, and then her eyes widened and she screamed out, ‘Oh my God, it’s her!’

The whole room was suddenly thrown into confusion. Merle, Faith and Norrie all stopped work and stared at their elder sister, mouths falling open. Heather, still leaning against the back of her mother’s chair, gave a startled leap, then lost her balance and almost fell as her elbow skidded off the old chair’s slippery leather. Jinty, about to take another sip of tea, also jumped, and hot tea slopped over the rim of the cup on to her hand.

‘Steph! For God’s-goodness’ sake, what’s got into you?’

‘It’s her!’ Steph, oblivious to the chaos she had caused, pointed a trembling hand at the screen, where Imogen Goldberg was gracefully taking her final breath. ‘I thought I knew her because she lived here, but it was because I’ve seen her on the telly! That woman – she’s the one who drove into Prior’s Ford this afternoon when we were all getting off the school bus!’

During dinner, a. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...