- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

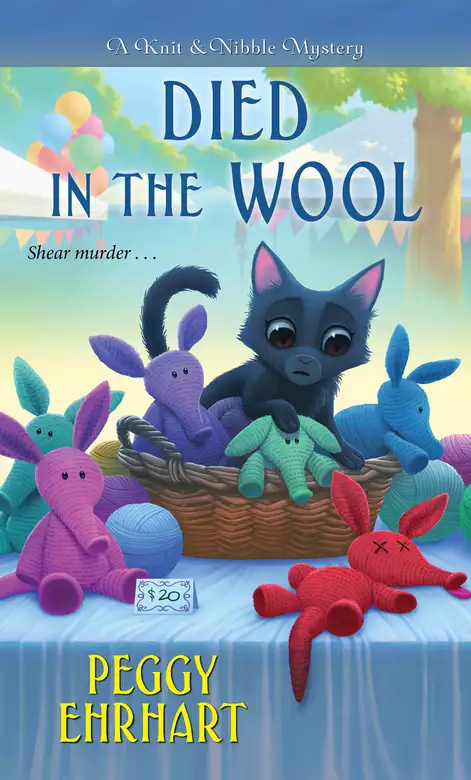

When a murder shocks picturesque Arborville, New Jersey, Pamela Paterson and her Knit and Nibble knitting club suddenly find themselves at the center of the investigation — as suspects....

Pamela is ready to kick back and relax after a busy day selling stuffed aardvarks to benefit Arborville High School's sports program at the annual town festival. But just as she's packing up, she makes a terrible discovery — someone's stashed a body under the Knit and Nibble's table. The victim is Randall Jefferson, a decidedly unpopular history teacher after his recent op-ed criticizing the school's sports program. But the primary suspect has an alibi, and the only clue is a stuffed aardvark found on the victim's chest....

Now the Knit and Nibblers must unravel the case quickly-before a crafty killer repeats a deadly pattern.

Release date: August 28, 2018

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Died in the Wool

Peggy Ehrhart

“Actually”—Bettina Fraser reached across the table to lift it out of his hands and set it back among its fuzzy turquoise companions—“I believe that’s one I made.”

“I beg to differ—” Roland picked it up again and pointed to the shiny black buttons that marked its eyes. “I particularly remember using these buttons. Your buttons were different—see, look here.” He seized another aardvark by the scruff of its neck and turned its head toward Bettina. “Not as shiny.”

Pamela Paterson slipped around the table to join Bettina. “They all turned out beautifully,” she said. “The one with the shiny eyes is definitely yours, Roland.” Pamela was the founder and mainstay of the Arborville knitting club. Bettina was her best friend, but Roland was the only male member of the club. Sometimes he needed someone on his side. “And I’m sure we’ll sell them. Sports mascots in the school colors—well, one of the school colors at least. Who could resist? And it’s for such a good cause.”

Arborville High School’s colors were turquoise and gold, and the occasion was Arborfest, Arborville’s annual town celebration, held the Sunday after Mother’s Day. The knitting club, known to its members as Knit and Nibble, had been at work for weeks producing the aardvarks now arrayed on the table. Money from the sale of the creatures was to go to the high school’s athletic program. On a corner of the table not occupied by aardvarks was a pile of flyers describing the knitting club.

Arborfest had begun at eleven a.m. with a parade down Arborville Avenue, featuring Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts, Cub Scouts and Brownies, the mayor and town council in vintage cars, and the high school’s marching band. Now the festival was in full swing. Two rows of booths faced each other across the asphalt expanse of the library parking lot. The Arborville chapter of the Community Chest was represented, serving slices of a huge sheet cake celebrating the group’s one hundredth anniversary in the town. And the Lions Club and Chamber of Commerce had booths, as well as the library, the recreation center, and the historical society. The Arborville pizza parlor, When in Rome, offered samples of three kinds of pizza, and the Chinese takeout restaurant offered dumplings, fried on the spot, creating a tantalizing aroma. The Co-Op Grocery’s booth highlighted its bakery, with trays of gingerbread cookies shaped like the letter A, for Arborville. Inside the library, a display of old photos and newspaper clippings focused on the high points of the high school’s athletic program.

On a stage at the end of the parking lot, the high school’s jazz-rock band was playing a lively tune. It featured enthusiastic horn parts, and the horns glinted golden in the midday sun. Beyond the parking lot, in the grassy expanse of Arborville’s park, a petting zoo had been set up, with lambs, baby goats, and rabbits. Pony rides were available for the children, and a clown capered about on the lawn, pausing now and then to juggle a bright collection of balls.

“Yes,” Pamela repeated, to Bettina this time. Roland had wandered off to join his wife, and they were sampling pizza at the When in Rome booth. “It’s a very good cause.”

“I’m sure he’d agree.” Bettina nodded toward a sturdy young man in a turquoise “Arborville Aardvarks” T-shirt. He caught Bettina’s eye and strolled over.

“How are you doing?” he asked.

“Brad Striker,” Bettina explained. “The new football coach. I interviewed him for the Advocate last fall.” Pamela reached out her hand and supplied her name. The coach had the square jaw and strong brows of a comic-book hero, and he grasped her hand without smiling.

“I’m glad to see the knitters approve of high-school sports,” he said, letting go of her hand after a firm squeeze and reaching for an aardvark. “Not like that”—he paused, as if censoring the word he’d planned to use—“that . . . that idiot history teacher.”

“Did you see last week’s Advocate?” Bettina asked Pamela. The Arborville Advocate was the town’s weekly newspaper, and as the paper’s chief reporter, Bettina covered most of the town news.

Pamela hesitated. “I know I brought it in.” No one actually subscribed to the Advocate—it just arrived, generally midweek, at the end of one’s driveway. “I’m not sure I read the whole thing.”

“Randall Jefferson can be a very nasty man,” Bettina said. “But, freedom of the press and all. He must be busy, with the school year winding down, but he took the time to sit down and unburden himself on the subject of high-school sports.”

“Not in favor?” Pamela asked.

“Most definitely not in favor.” Bettina laughed. “You got that right. The high-school sports program should be abolished, especially football. He noted that the students are stupid enough already without rattling their brains on the football field, and if they spent more time studying history they’d be better citizens. People who don’t remember the past are condemned to repeat it and so on.”

Brad Striker didn’t laugh. “Like I said, an idiot.” He shoved his hands in his pockets and swung his head from side to side as if he was scouting the crowd for the object of his irritation. “They say he’s got so much money he wouldn’t even have to work if he didn’t want to. Why doesn’t he just stay home and mind his own business then?”

“Can’t the students do both?” Pamela inquired. “Sports and history?” Pamela herself had never enjoyed team sports, preferring to get her exercise by doing errands on foot, a luxury that the tiny town of Arborville allowed.

Brad Striker frowned, as if even a compromise was an insult. “Idiot,” he muttered again and wandered off toward a rowdy group of young men wearing T-shirts just like his.

Bettina touched Pamela’s arm. “I don’t think he meant you were an idiot,” she said soothingly.

Pamela, meanwhile, was handing over two aardvarks to a tall, smiling man who immediately gave one to each of the excited little boys bouncing at his side. “Our first sale,” she said, smoothing out two twenty-dollar bills and placing them in the metal cash box.

Young couples in shorts and T-shirts strolled with their children, balloons on long strings bobbing along behind them. Teenagers stood in tight knots, segregated by gender, the girls giggling and watching the boys, and the boys trying not to be obvious about watching the girls. Older couples ambled along, pausing to greet old friends.

“Such a perfect day for this,” Bettina said, beaming. “The booths look so nice, and the volunteers worked overtime to finish the rock garden. That handsome Joe Taylor really got them organized.” She turned toward the library to survey the little plot, bordered by carefully arranged rocks, then turned back toward the crowd. “Oh, look!” she said suddenly. “Richard Larkin is here with his daughters.” Bettina nodded toward a tall man in torn and faded jeans standing with two young, twentyish women. “Why don’t you go over and say hello? This is his first Arborfest. I can certainly manage the booth myself for a while.”

Pamela had been the object of her friend’s matchmaking efforts since the previous fall, when Richard Larkin—recently divorced—moved into the house next to Pamela’s own.

“I said hello to him this morning,” Pamela said. “He was bringing in his newspaper while I was loading the aardvarks into my car.”

“Well, go say hello again.” Bettina gave her a friendly nudge. “Ask him if he’s having a good time. You said you’d think about dating again when Penny started college, and now she’s already finished her freshman year and you’re still all alone in that big house.”

“Penny is home for the summer,” Pamela said. “And he’s really not my type.”

Richard Larkin wasn’t unattractive. Pamela would grant that, though the jeans seemed an affectation—too artistically torn and faded, like something a city hipster would buy at a SoHo boutique, and his hair was too shaggy. He was smiling now, in a way that softened his strong features. She looked away when his gaze turned in her direction.

“Why don’t you take a walk anyway?” Bettina said. “You did all the booth setup before the parade. I can handle things for a while—” She paused to accept a twenty-dollar bill from a grandmotherly woman and hand over an aardvark.

“Lovely idea,” the woman commented. “So clever.”

Pamela eased herself around the side of the table. “I am a little hungry,” she said, “and those dumplings smell heavenly.”

“Will you bring me one?” Bettina asked.

“Just one? I think they’re kind of small.”

Bettina patted her ample waistline. “I know you could eat ten of them and not gain an ounce, but I’m not so lucky. And I’ll never understand why you wear the same jeans every day when you could show off that tall skinny figure of yours.” Pamela indeed was dressed in her summer uniform of jeans and a casual cotton blouse. Bettina, who loved clothes, was wearing a floaty sundress in shades of scarlet, purple, and green. The scarlet was nearly the same shade as her hair.

“I’d like an aardvark,” said a little voice at Pamela’s side. She looked down to see a pigtailed girl not much taller than the table handing over a twenty-dollar bill.

Bettina completed the transaction, and Pamela went on her way to fetch dumplings. “No hurry,” Bettina called after her. “Take your time.”

Pamela detoured around a knot of giggling girls, found herself bouncing along with extra spring in her step, and realized she was moving in time with the syncopated drums and tootling horns of the jazz-rock band. She smiled and glanced toward the stage.

“Hello, Pamela!”

At the sound of her name, Pamela stopped suddenly. She’d been so distracted by the music that she’d almost stepped on Nell Bascomb’s toes.

“It’s fun to hear the kids play this old music, isn’t it?” Nell said. “I think that’s ‘Take Five.’ Harold and I used to love to go down to the Village to hear jazz.” Nell was a fellow member of Knit and Nibble and a long-time Arborville resident, much livelier and more outspoken than her white hair and wrinkled skin would suggest. “We just got here, and Harold is already off talking to his pals from the historical society. Bettina’s Wilfred is there too. How are we doing with the aardvark sales?”

“Four sold so far, twenty-one to go.”

“Oh, look—” Nell pointed toward the knitting club booth, where Bettina was dealing with a small crowd, handing over one aardvark after another.

A tiny boy with a balloon came hurtling by and was quickly scooped up by his mother. “Shall we go pet a goat?” she asked, smoothing his hair back from his forehead.

“I’ll give Bettina a hand,” Nell said. She took a few steps and paused. The jazz-rock band had wrapped up “Take Five” with a flourish and conversations going on around them were suddenly audible. “Brad Striker,” Nell said. “Over there.”

Standing near the rock garden, Brad Striker was holding forth to a man dressed like he was, in a turquoise T-shirt with the Arborville Aardvark logo. The subject seemed to be Randall Jefferson’s op-ed piece in the Advocate, and the language Brad was using wasn’t confined to the fairly mild word “idiot.”

“I have to say that Randall had a point,” Nell confessed, “though he could have been much more diplomatic. I was happy to do my part with the aardvarks, but football does rattle the brain.”

Pamela sighed. “Well, everyone will have the summer to cool off. And Randall Jefferson definitely has his supporters at the high school.” She continued on her way toward the dumplings.

But Bettina had said to take her time, so she detoured around the row of booths that flanked the park. The lawn was the rich green of late spring, and the May sun made the colors of everything seem brighter. Children scampered here and there, watched by parents chatting in groups. A clown shaped a long balloon into a yellow dachshund.

A terrified shriek, out of keeping with the atmosphere, drew her attention to the petting zoo. Within a low wire fence held up by stakes, a young woman was trying to introduce a hesitant little girl to a baby goat. The goat stared with huge eyes at the girl as the girl backed into the embrace of her mother. Other children weren’t so hesitant. The goat stood patiently as many tiny hands explored its furry coat.

“Hey, Mom,” said a voice behind her. “Waiting for your turn to pet a goat?”

Pamela turned to see her daughter Penny, accompanied by Richard Larkin and his two daughters. Like their father, they were tall and blond.

“Interesting event,” Richard said, letting his eyes rove over the crowd. “I guess these kinds of things are a big deal in little towns.”

“Dad!” His oldest daughter, the one named Laine, laughingly jabbed his arm. “You sound like a complete snob.”

He blinked a few times. “I meant—”

“We know what you meant, Dad.” This came from Sybil. She grabbed Penny’s arm. “Come on, let’s go pet a goat.” The three of them bounced off together, little Penny with her short dark curls between the two lanky blondes.

Suddenly Pamela and Richard Larkin were alone—at least as alone as it was possible to be in the midst of Arborfest.

“I . . . uh . . .” Richard rubbed his forehead and let his eyes rove over the crowd again. “How is your group doing with the armadillos?” he asked suddenly.

“Aardvarks,” Pamela said. “They’re aardvarks.”

“Of course,” he said. “I meant aardvarks.”

“Pretty well,” Pamela said. “It’s for a worthy cause, you know. The high-school sports program.” When he didn’t respond, she went on. “Kind of controversial.”

“Um.”

If he’s not interested in the topic, why doesn’t he just excuse himself and go away, Pamela wondered. But his eyes looked so desperate. “Did you see the op-ed piece in the Advocate?” she asked. Maybe he just needed a conversational topic.

“Is that the thing that turns up at the end of the driveway every week?” he said with a laugh. “I usually run over it with my car.”

“It’s the Arborville weekly,” Pamela said. “Bettina writes for it—most of the articles, in fact. Lots of people in town enjoy it.”

“Oh”—he blinked, clapped his hands briskly, and looked around. “I think it’s time to go buy an aardvark,” he said. And he was gone. From the stage came the sound of horns as the band started up again.

At the dumpling booth, Pamela waited her turn, watching as Jamie Chin tended a batch of plump dumplings and enjoying the tantalizing aroma of the smoke drifting up from the wok. She came away with two sets of chopsticks and a small paper plate containing four dumplings. Waving at Wilfred as she passed the historical society booth, she was soon back at Bettina’s side.

“Richard Larkin bought an aardvark,” Bettina said before she even reached for the plate of dumplings. Then she captured a dumpling with a pair of chopsticks and conveyed it to her mouth. “Ummm . . . heavenly.” She smiled and reached for another.

“How are we doing?” Pamela surveyed the table, where only a few clusters of aardvarks remained.

“Eat your dumplings,” Bettina said, “then we’ll take stock.”

“Bean sprouts and shrimp,” Pamela said, after biting into the warm, spicy tidbit. “Yum.” She finished off the first dumpling in two bites and started on the second. Meanwhile, Bettina opened the metal box that had been serving as the till. She counted the bills, mostly twenties, and announced that they had taken in $280.

Pamela reached down to pull the remaining aardvarks from the cardboard box they’d arrived in and lined them up with the ones on the table. “Nine left.” She paused. “But wait—there should be more than two hundred and eighty dollars then. There should be three hundred and twenty dollars, for sixteen aardvarks sold.”

“Two missing!” Bettina looked stricken, her hazel eyes wide. “I was here the whole time—except for the parade.”

“But they were all still in the boxes then,” Pamela said, “tucked away inside the booth. We hadn’t set up yet.”

“Someone has stolen two aardvarks.” Bettina’s lips twisted as if she was about to cry.

“Dear wife, what has happened?” It was Wilfred, Bettina’s husband, his usually cheerful face mirroring his wife’s unhappiness.

“Someone has stolen two aardvarks,” she repeated. “There are nine left but we only have money for fourteen.”

“Misfortunes never come single,” Wilfred murmured and leaned across the table to pat Bettina on the shoulder. “But perhaps they went to children whose families couldn’t afford twenty dollars.” He slid his hand down her arm and grasped her fingers. “It’s not the end of the world. Come away with me, dearest, and say hello to the people at the historical society booth.”

Pamela watched them make their way through the milling crowd, Wilfred’s white-thatched head bending toward Bettina’s. Husbands could be a great comfort, she reflected. But she was glad when a woman offering a twenty-dollar bill and claiming an aardvark distracted her from pursuing that thought to its logical conclusion.

To distract herself further, she re-counted the money they had taken in so far. The recent sale had brought the total to three hundred dollars, but there were now only eight aardvarks waiting to be sold. Very puzzling. It was possible someone had gotten into the boxes while she and Bettina were at the parade. They’d made no secret of the fact that the boxes contained the aardvarks as people bustled here and there that morning preparing their booths. She’d chatted with someone from the Arborville Chamber of Commerce in the booth next door, and a few volunteers had been making sure the rock garden behind the library hadn’t sprouted any weeds since its completion. Joe Taylor had exclaimed, “Nice varks!” and complimented her on the clever idea of enlisting the knitting group’s support of the sports program.

The next few hours passed quickly. Penny stopped by with Richard Larkin’s daughters to say that they were all going to walk to Richard’s house and hang out for awhile. Nell and Harold came by to check on sales and report that the historical society had recruited three new members. Pamela sold four more aardvarks. Bettina returned and insisted that Pamela take another stroll around the parking lot.

Pamela made a slow circuit, pausing to watch the ponies climb up a ramp into their truck. The petting zoo was closing down as well, and one of the lambs scampered away as it was being led through the gate in the zoo’s temporary wire fence. It dashed across the grass and was captured at last near the tennis courts. Families trooped out of the park and along the edge of the parking lot, heading toward the street.

Back at the booth, Pamela discovered that only one aardvark was left. “I think that’s it,” Bettina said. The asphalt area between the two rows of booths was emptying out as well, and booths were being dismantled. The chimes from St. Willibrod’s, the grand stone church on Arborville Avenue, sounded the hour. It was five o’clock, time to pack up.

Bettina tucked the lone aardvark into one of the cardboard boxes they’d arrived in while Pamela climbed on a chair to detach the Arborville Knitting Club banner they’d strung across the front of the booth. She gently rolled it up, and then began to detach the canvas they’d tacked around the table the previous evening. But as she pulled the front panel loose, she stopped and stared. She felt her body twitch as if a tiny, local earthquake had affected the spot of parking lot where she stood.

A person was under the table, a man. He was lying on his back, and on his chest was perched a knitted turquoise aardvark. She looked up. Bettina was cheerfully counting the money again, fingers busy as she slipped bills from one hand to the other.

Bettina paused.

“Pamela?” She raised her brows. “You look like you’ve seen a ghost.”

From behind her, Pamela heard another voice, the voice of an excited child. “Mommy!” the voice said. “There’s a dead person under there. The aardvark killed him.”

“What?” Bettina raised her brows even farther. She hastily dropped the stack of bills back into the metal box, slammed the cover shut, and eas. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...