- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

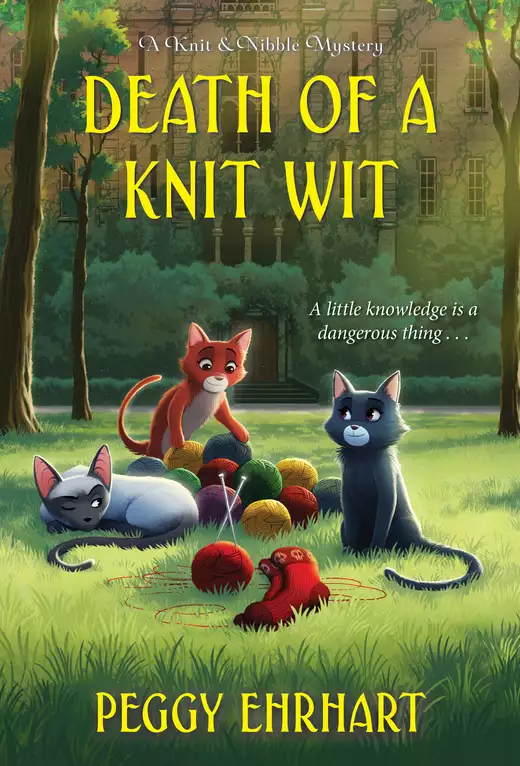

Synopsis

When a professor is poisoned, Pamela Paterson and the members of the Knit and Nibble knitting club must take a crash course in solving his mysterious murder.

Pamela has organized a weekend-long knitting bee as part of a conference on fiber arts and crafts at Wendelstaff College. But when pompous Professor Robert Greer-Gordon Critter, the keynote speaker at the conference, crashes the bee, he seems more interested in flirting than knitting. The man's reputation as a philanderer supersedes his academic reputation. After coffee and cookies are served, the professor suddenly collapses, seemingly poisoned—but how? Everyone had the coffee and cookies. Joined by her bestie Bettina and the Knit and Nibble ladies, Pamela sorts through everything from red socks to red herrings to unravel the means and motives of a killer dead set on teaching the professor a lesson . . .

Release date: February 22, 2022

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Death of a Knit Wit

Peggy Ehrhart

Now the conference was wrapping up. The keynote speaker’s luncheon talk was nearing its end, then would come a few more workshops and the afternoon session of the knitting bee that had been Pamela’s idea. That evening a gala banquet would climax a satisfying week devoted to fiber.

At the moment, all eyes were focused on a podium at one end of the Wendelstaff dining hall. There Dr. Robert Greer-Gordon Critter stood behind a lectern, every inch the professor with his well-trimmed hair graying at the temples, his horn-rimmed glasses, and the bow tie that lent a jaunty note to his expertly tailored tweeds.

“And so to conclude,” he intoned, lifting what was presumably the last page of his talk, “not nearly enough credit has heretofore been given to the role of spun fiber in the advance of civilization and the success of the human enterprise.”

He removed his glasses, smiled, and nodded in acknowledgment of the applause that followed.

“Questions?” He glanced around the large room.

A woman sitting at a table near the podium hopped to her feet and began speaking. “I read your book,” she said in an accusing tone. “And you jump to conclusions no one with a solid grounding in the archeological evidence for spindle development would have jumped to. In fact I would even say—”

Critter waved a dismissive hand and smiled a dismissive smile. “I leave the minutia to those who can’t see the forest for the trees. I am a theorist.” He looked out over the room. “Next question?”

“You can’t just brush me off like that.” The woman remained on her feet. She was fiftyish, and attractive, wearing a dress sewn from rustic, gaily dyed fabric. “Anyone can make up theories if they don’t have to pay attention to facts. For example, spindles have been unearthed in regions that actually never made the technological advances you point to as a result of spun fibers, and—”

Critter smiled again, but less confidently. “Other questions?” He pointedly looked toward the room’s farthest corner. Pamela swiveled her head to follow his gaze. A hand waved in the air and he nodded gratefully. But before the new questioner could even rise, the persistent woman near the podium went on.

“What about the Westvelt hoard? Spindles galore, and yet until the Romans—”

“You, in the back.” Critter nodded, raising his voice.

But the woman was not to be silenced. “And the Mesopotamian burial chambers?” Her voice rose in pitch. “You don’t even—”

“I don’t even what?” Critter leaned over the lectern, a frown disfiguring his bland features.

“Have any ideas of your own, except the bad ones!”

Critter swept up the bundle of papers containing his talk and stepped back from the lectern. “Thank you very much!” he growled, nodding at the dean of humanities, Louise Tate, who had introduced him. “Very much.” He retreated toward the exit behind the podium as the woman called after him, “You stole all my good ideas and polluted them with your bad ideas.”

A college maintenance man, gray-haired but fit, who had been helping with the conference lingered near the door. Critter paused for a moment before pushing the door open. The maintenance man nodded, fished a pack of cigarettes from his pocket, and extended it toward the professor.

As the door closed behind him, Dean Tate closed her eyes and let her shoulders sag. She was a petite blonde woman with a pixie-cut hairstyle. “Oh . . . my . . . goodness,” she sighed as Pamela approached. She looked up and smiled weakly, as if sensing that Pamela’s intent was to commiserate. “I knew the split wasn’t amicable,” she moaned, “but I thought Yvonne would just be happy to go her own way with him out of her life.”

“I guess you know her.” Pamela pulled up the chair on which Critter had perched while Dean Tate detailed his many accomplishments for the audience that had assembled to hear him.

Dean Tate nodded. “Yvonne Critter—now it’s Yvonne Graves—was a regular at School of Humanities social events until a few years ago, when their marriage started to disintegrate.”

“At least she waited till his talk was over,” Pamela said. “So the conference-goers didn’t miss out. I’m sure a lot of them came to the conference because they had read Spinning Civilization and were eager to see and hear R. G.-G. Critter in person.”

“You’re so kind!” Dean Tate reached for Pamela’s hand. “I do sometimes need a reminder to look on the bright side.” She shook her head. “But honestly, sometimes I feel that I’m the principal of a middle school and not a dean at all. The childish intrigues! The gossip! The feuds! You’d think professors’ minds would be on higher things.” She leaned forward confidingly. “You’re lucky you work at home.”

Pamela did feel lucky. As associate editor of Fiber Craft magazine, she spent most workdays at the computer in her pleasant home office, where she evaluated articles submitted to the magazine and copyedited ones that had been selected for publication. Rarely did her job require an in-person appearance anywhere—only the occasional meeting at the magazine’s offices in the city or events like this one: the conference on fiber arts and crafts co-sponsored by Fiber Craft and Wendelstaff College.

Pamela looked at her watch. “I should get back over to Sufficiency House,” she said. “The knitters will be wondering where I’ve disappeared to.”

“You’ll be seeing R. G.-G. again.” Dean Tate raised her brows and twisted her lips into a humorless smile. “He’s planning to drop in at Sufficiency House for coffee this afternoon. I hope he’s recovered by then.”

The exit behind the podium was closest to the parking lot where Pamela’s car waited. As she walked past the attractive cluster of tall shrubs that softened the utilitarian lines of the dining hall, she heard a familiar male voice. The voice was as assertive as it had been when explaining to a rapt audience how important spun fiber had been to the advance of civilization. But now it seemed to be responding to a lament.

“You jumped right into it,” the male voice said. “Nobody forced you.”

“But you acted like you . . . cared for me,” a woman whimpered. “And I trusted you. And now I feel so . . . let down. Like I was a fool.”

“We’re both grown-ups.”

Pamela halted. How could anyone be so cruel in the face of such misery? Even someone who’d just endured public criticism of his new book?

“I admired you,” the woman went on. “You’re brilliant. And when you kissed me and . . . the rest . . . and it seemed that we were going to be . . . a couple, I was so amazed, I had to pinch myself.”

If the conversation hadn’t already revealed that this woman was not Yvonne, her voice—with its nasal twang and unexpected diphthongs—hinted at a stratum of society far removed from the educated circles that were home to Dr. Critter.

Sufficiency House was at the northern edge of Arborville, just across the border from the town where Wendelstaff College was located. It had been the home of a Depression-era crusader, Micah Dorset, who taught classes and wrote pamphlets encouraging people to grow their own food and make their own clothes. It had been given to Wendelstaff several decades previously by Dorset’s heirs and now existed as a museum and information center.

Ten minutes later Pamela nosed her car to the curb in front of the house, a Craftsman bungalow painted a soothing shade of green. A wide porch spanned the entire width of the house, shaded by a low roof supported by massive angular pillars. Sufficiency House occupied a lot on a residential street, but it differed from its neighbors in that instead of a lawn, its front yard had been given over to food production.

Rows of waist-high tomato plants bearing heavy fruit in every shade from green to deep red gave way to luxuriant vines from which dangled pods bulging with beans and peas. Feathery dark-green carrot tops and darker green beet leaves announced that root vegetables lay beneath the ground. A tidy brick walk led from the sidewalk to the porch steps.

Pamela paused to admire the tomatoes, wishing that her yard was sunny enough to grow more than a few tomato plants. She stroked a hairy leaf and inhaled the tomato aroma that rose even from the plant’s foliage.

As she climbed the steps, the front door opened and Flower Ransom—or Flo, as she preferred to be called—sang out a greeting. Flo was Sufficiency House’s live-in caretaker and docent. As she had once told Pamela, she had shortened the name given her at birth by her hippie parents into a single syllable with a more old-timey feel. Totally caught up in her position, she wore her gray-streaked hair in an austere roll at the back of her head and limited her wardrobe to clothing that would have been worn in Micah Dorset’s era. Today’s ensemble was a much-washed cotton housedress faded to an indeterminate shade of pale blue, accessorized with lace-up shoes in brown leather.

“We’re keeping up the momentum,” she chirped, stepping aside to let Pamela enter.

Seated around the room, some on the nubbly tan sofa, one in a roomy upholstered chair with broad wooden arms, one on a matching hassock, and others on wooden chairs imported from other parts of the house, were knitters. Their ages varied, but all were women.

The knitting bee had been Pamela’s contribution to the conference program, open to all with an interest in knitting. Participants were invited to bring their projects, or—if they were not yet knitters—to bring yarn and knitting needles. After morning coffee, experienced knitters had paired with beginners. Soon needles had begun clicking, and the room had resounded with the pleasant chatter of women whose hands were busy but whose minds were free to roam. Such bees were common during the Depression, she knew, when frugality was essential to survival and purchased clothing was a luxury out of reach for so many.

Pamela returned to the chair she had vacated earlier and drew her own in-progress work from her knitting bag. She had recently finished a sweater for her best friend, Bettina Fraser, a fellow member of Arborville’s Knit and Nibble knitting club, but with skills less advanced.

The sweater for Bettina had used a complicated seersucker stitch that required careful counting of knits and purls, but Pamela’s current work in progress was considerably simpler, if no less altruistic. Nell Bascomb, another member of Knit and Nibble, put her knitting talents to charitable use and Pamela had joined Nell in one of her do-good projects: winter scarves for the Guatemalan day laborers.

Happy that the garter stitch the scarf was worked in allowed her mind to wander at will, Pamela launched a new row and fell happily to work. The projects taking shape in the laps of the other knitting bee participants ranged from a very ambitious Fair Isle cardigan to the beginnings of a humble scarf not unlike the one that hung from Pamela’s own needles.

Quiet conversations had sprung up around the room, gray heads bending toward brighter tresses—one young participant even had green hair. Experienced knitters were fielding questions from the beginners as other people chatted about their children or their husbands or their classes or their other hobbies.

Pamela’s chair was right next to Flo’s, and the seating arrangement was such that a large gap, allowing access to the dining room, yawned between Flo and the knitter on her other side. Pamela enjoyed hearing chatter around her as her mind wandered freely, unconstrained by the need to keep up her end of a conversation. But Flo had been so helpful in arranging the details of the bee, and if she was to have anyone to chat with, it would have to be Pamela. So Pamela mustered her social smile and dipped her head toward the sock nearing completion on Flo’s busy needles.

The sock’s color, a muted red, was quite unusual, and that provided Pamela with her opening gambit.

“I love that color,” she said. “Is your yarn from the Timberley yarn shop?”

Timberley was the next town north of Arborville. It boasted a wider—and fancier—array of shops than those found in Arborville’s commercial district, as befitting the higher per capita income of Timberley’s residents. Among those shops was one that sold yarn from every fiber-producing region one could imagine. A knitter wanting to move beyond hobby-shop acrylic could easily spend as much on yarn there as one would pay for a sweater from the fanciest store at the mall.

“Oh, no!” Flo sounded horrified, though in a gentle way. “I try to live by Micah Dorset’s tenets. ‘Use it up, wear it out, make it do, or do without.’ I unraveled a wool sweater that had already given me years of wear and I redyed the yarn with natural dye sourced from the Sufficiency House garden.”

“The red is beautiful,” Pamela said. “What color was the sweater you unraveled?”

“Beige, basically. It was that oatmeal kind of yarn. So the dye came up really nice.” Flo had a pleasant, undemanding face, with guileless pale blue eyes. She looked no younger than her fifty or so years, but those years had been kind.

“What plant makes that shade?” Pamela asked, reaching over to finger the strand of yarn that led from the ball in Flo’s lap to the work on her needles.

“Bloodroot,” was the response. “Not the leaves or the petals though. You have to dig up the rhizomes. But it spreads willingly, so more always grows as long as you leave a few rhizomes behind.”

At that moment, the door that led to the kitchen swung open and a young woman, a Wendelstaff student who Pamela recognized as one of the conference aides, popped out.

“Coffee and cookies are here,” she announced. With the door open, a rich and tantalizing aroma advertised the coffee’s presence.

Flo lowered her knitting into the basket at her chair’s side and rose to her feet. Pointing around the room and murmuring the numbers to herself, she counted the knitters: ten, in addition to her and Pamela.

She darted through the dining room door and Pamela followed her through that room and into the kitchen. The Sufficiency House kitchen had been preserved in its 1930s state—or perhaps restored to that condition. Large black and white tiles in a checkerboard pattern covered the floor. The stove and refrigerator, both gleaming white enamel, were elevated on legs that seemed too spindly to bear their weight. A gray soapstone counter was interrupted by a deep metal sink.

A wooden table stood against the wall that wasn’t occupied by counter or appliances. It now held coffee in a tall stainless steel dispenser with a spigot and hot water in a similar but smaller dispenser, as well as cream and sugar, a bowl containing tea bags, and a tray of large chocolate chip cookies.

Flo was busily filling mismatched but attractive china cups with coffee and nestling them into the saucers that awaited them on another, larger, tray.

“The cups and saucers are my own collection,” Flo said, “from thrift stores and tag sales. When Sufficiency House hosts events, it seems appropriate to serve refreshments as they might have been served in Micah Dorset’s time. People still had nice things from before the Depression, and I’m sure they enjoyed bringing them out.”

She left to carry the first six cups of coffee to the dining room and take orders for tea, and Pamela followed with the tray of cookies. Additional trips supplied tea for the tea drinkers, more coffee, cream and sugar, small plates, napkins, and spoons. Some knitters perched on chairs at the dining room table, while others took their refreshments back to the living room, where they clustered around the coffee table.

Chatter, punctuated by laughter, grew louder under the influence of caffeine, and the atmosphere became quite partylike. Flo had remained in the dining room, but Pamela had pulled her chair up to the coffee table and was enjoying a conversation with the woman working on the Fair Isle sweater. The woman was describing her trip to the Shetland Islands for Wool Week in such glowing terms that Pamela had begun to mentally examine her budget for the next year with an eye to experiencing Wool Week for herself.

Her calculations were interrupted, however, when the door of Sufficiency House opened. A familiar voice boomed, “Good afternoon, ladies!” and R. G.-G. Critter strode into the room, elegantly professorial in his tweeds and horn-rimmed glasses. A faint drift of cigarette smoke followed in his wake, and from the porch a man called, “I’ll be back for you in an hour.”

Critter paused in the middle of the room for a moment, as if to allow time for admiration. He had clearly recovered from the experience of having his work challenged by his ex-wife. Even if he hadn’t, Flo’s solicitous approach would have soothed his pride.

“Dr. Critter!” she exclaimed as a smile warmed her gentle face. “I’m so glad you were able to make it! Was that Bob Lombard on the porch?”

Critter nodded.

Pamela stood up to greet the guest as well. In an aside, Flo explained that Bob was one of Wendelstaff’s maintenance people and he’d been invaluable in helping the conference run smoothly.

Some women had drifted in from the dining room and others had risen from their seats in the living room. Soon Critter was surrounded, accepting compliments on his talk and answering questions about his research. His aura seemed not to have been dimmed by his ex-wife’s claim that all his good ideas were actually hers.

“And what are you all working on?” he inquired as compliments and questions trailed off, addressing himself particularly to the youngest participant in the bee, whose green hair detracted not one bit from her attractiveness.

She stepped away to seize up her knitting project, a simple scarf in an orange mohair, perhaps chosen for the eye-catching statement the finished product would make with her interesting hair color.

Flo had been observing at a distance, obviously pleased with the success of the refreshments and the warm welcome Critter was receiving. Suddenly, though, she raised a hand to her cheek and exclaimed, “I’m forgetting my manners! Dr. Critter, let me get you some coffee! And there are chocolate chip cookies.”

She took a few steps toward the door that led to the dining room and the kitchen beyond. But Critter stopped her, saying, “I can serve myself.” He directed a smile at the green-haired woman. “I’m very liberated.”

As he stepped through the door to the dining room, Flo called, “Coffee’s all the way back in the kitchen and there’s one more cup and saucer.”

Soon he was back, pulling one of the wooden chairs closer to the coffee table, sipping his coffee, and chatting with the women around him. A few on the sofa had taken up their knitting again, but others were still nibbling on cookies or finishing up their coffee. Pamela had returned to her chair. From her vantage point, she could see Flo tidying up the dining room table, stacking abandoned cups and saucers on the tray that had held the cookies.

A sound like a stifled hiccup drew her attention to the group around the coffee table. She could see only Critter’s profile, but his face seemed flushed. Everyone around him was looking at him, but no one was laughing, or even smiling. She heard the sound again, like a dry cough, and it was coming from Critter, who had raised both hands to his chest. He began to snort.

At this point, Flo hurried in from the dining room, and a few women set their knitting down and rose to their feet. A plump middle-aged woman spoke up. “I’m a nurse,” she said, and with a few long strides she reached Critter’s chair and bent over him.

He flung his head back and began to gasp, and his face grew more flushed.

“An allergic reaction,” the nurse said. She looked up. “Were there nuts in the cookies?” Bending back down, she addressed Critter. “Do you carry an EpiPen?”

“Not allergic,” Critter managed to moan.

“He didn’t have any cookies,” the green-haired woman contributed.

Flo, meanwhile, had produced a cell phone from somewhere. Her fingers busied themselves on it as she murmured, “Nine-one-one.” Then she raised it to her ear and recited the address of Sufficiency House.

Critter had begun to twitch, so frightfully that the wooden chair he was sitting on threatened to topple. The woman who had been sitting in the roomy upholstered chair jumped up and said, “Have him sit here.” She pushed the chair sideways until it was lined up right next to Critter. The nurse and the green-haired woman each seized one of his arms, raised him slightly, and hefted him into it. He rested his head against its cushioned back, eyes closed, and began to pant. His hands, which had remained resting on his chest, clawed at his dapper bow tie.

“Loosen it! Loosen it!” someone urged. “He’s choking.”

Critter’s mouth dropped open. A sound like a low-pitched whistle emerged from his throat, repeating again and again.

Pamela watched, feeling short of breath herself and wondering if whatever was afflicting Critter was spreading, soon to afflict everyone who had taken part in the knitting bee. She scanned the faces that were focused so intently on the distressed man in their midst. She saw concern, certainly, alarm—even curiosity. No one else, however, appeared to be ill.

She inhaled deeply. Surely her body was reacting to the stress of this very unexpected event. Should she be doing more? The bee had been her idea. But Flo had summoned an ambulance, and a nurse was standing by—though not knowing what had brought on his distress, there was apparently not much else she could do.

Fortunately, at that moment a faint, high-pitched wail signaled the ambulance’s approach. The wail grew louder and louder, deafening almost, until it ceased abruptly, like a blasting radio that has suddenly lost its power supply. In the startling silence, Flo reached for Pamela’s hand and Pamela returned her comforting squeeze. Then feet sounded on the porch and Flo darted toward the door to admit the EMTs.

Pamela nodded when the banquet server, a Wendelstaff student, asked if she had finished. The salmon she had requested when the conference registration form asked her to choose. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...