- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

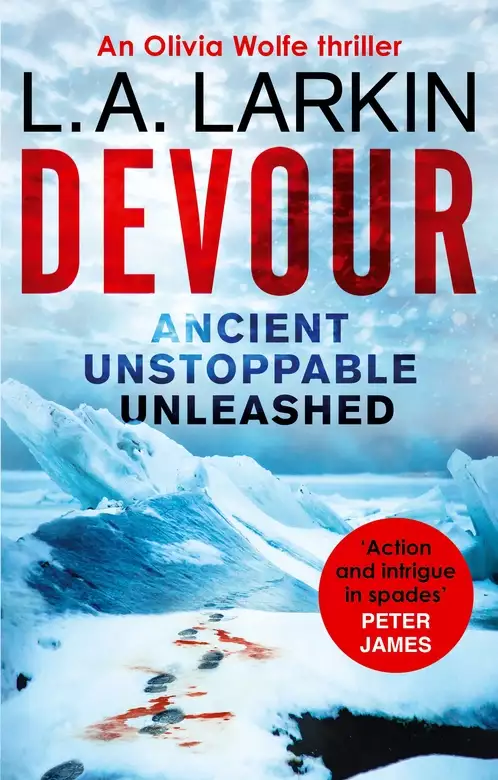

Synopsis

Their greatest fear was contaminating an ancient Antarctic lake, buried beneath the ice for millions of years. They little knew the catastrophe they were about to unleash.

Welcome to the high octane world of Olivia Wolfe.

As an investigative journalist, Wolfe lives her life in constant peril. Hunted by numerous enemies who are seldom what the first seem, she must unravel a complex web of lies to uncover an even more terrifying truth.

From the poppy palaces of Afghanistan and Antarctica's forbidding wind-swept ice sheets, to a top-secret military base in the Nevada desert, Wolfe's journey will ultimately lead her to a man who would obliterate civilisation. She must make an impossible choice: save a life - or prevent the death of millions.

Praise for L. A. Larkin:

'In Larkin, Michael Crichton has an heir apparent' The Guardian

'Larkin's fast action style is accompanied by impressive research' The Times

'Olivia Wolfe delivers action and intrigue in spades' Peter James

Release date: July 6, 2016

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Devour

L.A. Larkin

On the flat, featureless ice sheet, katabatic winds swoop down the mountain slopes, whipping up ice particles and hurling them at a solitary British camp. The huddle of red tents, blue shipping containers, grey drilling rig, and yellow water tanks are so tiny on the vast expanse of white, they resemble pieces on a Monopoly board. Three kilometres beneath the camp, subglacial Lake Ellsworth, and whatever secret it may hold, is sealed inside a frozen tomb.

In the largest tent, used as the mess and briefing room, Kevin Knox stands before Professor Michael Heatherton, the director of Project Persephone.

‘So how the hell did this happen?’ says Heatherton, dragging his fingers through greying hair.

Knox brushes away a drip running down his cold cheek, as ice, frozen to his ginger beard and eyelashes, melts in the tent’s comparative warmth. Outside it is minus twenty-six degrees Celsius but the wind chill makes it feel more like minus forty.

‘Mike, we don’t know exactly. The boiler circuit’s broken. It’ll need a new part.’

‘Don’t know?’ Heatherton scoffs.

Knox clenches his pudgy fists. What a thankless little twat! For the last hour he and Vitaly Yushkov, the two hot water drillers, have been struggling to fix the damn thing.

A strong hand squeezes his right arm and Knox glances at Yushkov standing beside him, whose penetrating blue eyes warn him not to lose his temper. Knox gives the Russian an almost imperceptible nod and Yushkov releases his grip.

Their leader gets out of his plastic chair and paces up and down behind one of three white trestle tables. A marathon runner of average height, he is lean, wiry and exceptionally fit for his age. But, next to Knox and Yushkov, he appears fragile. Knox isn’t tall but he is chunky, and likes to describe his wide girth as ‘love handles’ even if the Rothera Station lads pinned a photo on the noticeboard with his head photoshopped on to the body of an elephant seal. Not that it bothers him.

Yushkov is six foot one. His neck, almost as wide as his head, meets powerful shoulders, and his hands are so large they remind Knox of a bunch of calloused Lady Finger bananas. Knox knows little about Yushkov’s past – conscription, ship’s engineer, mechanical engineer – and the taciturn Russian doesn’t care to share. He is now a British citizen and the most talented mechanical engineer Knox has ever worked with, and that’s all that matters.

‘The eyes of the world are upon us,’ Heatherton says, his Yorkshire accent softened after years working with the British Antarctic Survey in Cambridge. ‘Everybody wants to know if there’s life down there.’ He momentarily looks at the rubber flooring beneath his boots. ‘And we’re only a kilometre away from the answer. We have to get the drill working again before the hole freezes over.’ His voice is high-pitched with agitation. ‘So what I need to know is, can you fix it?’

Yushkov speaks, his accent as strong as the day he last set foot in Mother Russia, sixteen years ago.

‘Boss, we built the hot water drill. We did not build the boiler. So, we need time to understand the problem. We will talk with manufacturer, get advice. We have spare parts at Rothera. If we are lucky, we get new circuit in a day or two and all is hunky-dory.’

Yushkov grins, revealing surprisingly perfect white teeth given his heavy smoking. Heatherton opens his mouth but Knox jumps in.

‘It’s going to be okay, Mike. We’ll get it running on a backup element and keep the tanks warm. Stop worrying.’

The taut skin around Heatherton’s eyes is getting darker each day. He plonks down into a chair and rubs his hands up and down his face, as if trying to wake up. He looks exhausted.

‘Look, Kev,’ he says through his splayed fingers, then drops his hands to his sides. ‘I’m a geoscientist, not an engineer. But to do my bit, I’m relying on you to do yours. I’m frustrated, that’s all.’

That is as close as Knox has heard their leader get to an apology.

Heatherton cranes his neck towards them, frowning, and speaks quietly so nobody can hear through the canvas walls. Not that anyone could anyway, given the blustering winds.

‘Could it be sabotage?’

Yushkov shifts from one battered boot to the other.

‘Pardon?’ Knox says. He can’t have heard right.

‘Has the boiler been sabotaged?’

‘Jesus, Mike!’ says Knox, flinging his hands in the air. ‘What’s got into you? We’re in the middle of bloody nowhere trying to do something that’s never been done before. Things go wrong. It’s inevitable.’

‘Yes, quite right.’ He sighs. ‘But a lot of things are going wrong. Too many. And we all know the Russians are trying to beat us.’ Heatherton flicks a look at Yushkov. ‘No offence.’

‘None taken,’ Yushkov replies, but the low rumble in his voice says he is not being entirely honest.

At that moment, BBC science correspondent, Charles Harvey, steps through the door, his black parka covered in snow, like dandruff. He’s as blind as a bat without his glasses, which means he’s constantly wiping ice off the lenses or cleaning them when they steam up.

‘Hear you’ve had a spot of bother. Mind if I join you?’

Heatherton hesitates. Harvey continues.

‘I see a great story here. Engineers struggle in howling storm to save project. That sort of thing.’

‘An heroic angle?’ Heatherton’s hazel eyes light up. He runs his fingers over his smooth chin, the only team member who bothers to shave. Knox knows why: Heatherton wants to look dashing in Harvey’s documentary. ‘I see. Okay.’ He looks at Knox. ‘Well, let’s get on with it.’

‘Fine,’ says Knox. ‘But if that blizzard gets much worse we’ll have to stop work and wait for it to pass.’

‘Yes, yes, health and safety and all that,’ Heatherton says, ‘Quite right. But if you don’t get the boiler working soon, this whole project is done for. Ten years down the toilet.’

Knox raises his eyes in exasperation. ‘No pressure then.’

As he zips up his black parka sporting the Lake Ellsworth project logo, tugs inner and outer gloves on to his hands, pulls on his beanie and hood and places snow goggles over his eyes, he thinks for the thousandth time what a stupid colour black is for Antarctic clothing. Should have been red, yellow or orange so they can be spotted easier. Through the flimsy door he hears the wind has picked up speed. It will be near impossible to hear each other above the roar.

‘Okay, mate,’ Knox says to Yushkov. ‘Let’s get this done as quick as we can. Stay close. Use hand signals.’

Yushkov nods.

‘Vitaly, a word,’ says Heatherton, gesturing him to stay.

‘Right. I’ll get started then. But I can’t do much without him, so make it quick, will you?’

Annoyed, Knox leaves, letting the fifty-mile-an-hour wind slam the door for him. The field site is a swirling mass of snow. He grips a thick rope, frozen so solid it feels like steel cable, secured at waist height between poles sticking out of the ice at regular intervals. Only thirty feet to the boiler. He carefully plants one boot after another. He staggers a few times. Head down, body bent, he throws his weight into the storm like a battering ram. Where the hell is Vitaly? That bloody Heatherton is probably wanking on about loyalty and reminding Yushkov, in his unsubtle way, that he now works for the Brits. The man is bloody paranoid.

Someone takes him in a bear hug from behind. He thinks Yushkov is mucking about, but when a cloth is held hard over his nose and mouth, he begins to panic. It has a chemical smell he can’t place. Confused and disoriented, he tries to turn. He feels light-headed and his eyelids droop.

Knox wakes. He hears a high-pitched buzzing, then realises it’s the retreating sound of a Bombardier Ski-Doo. Soon, all he can hear is the buffeting wind. He wants to sleep, but his violent shivering makes it impossible. He opens his heavy eyelids and sees nothing. Just white. Where is he? The hardness beneath his cheek tells him he’s lying on one side. Knox tries to sit up, but his head pounds like the worst hangover, so he lies back down. He blinks eyelashes laden with ice crystals, trying to take it all in. Of course. The boiler. He must have fallen. Maybe knocked his head?

This time, Knox manages to sit up and waits for the dizziness to pass. He can’t see the horizon or the surface he’s sitting on, or even his legs. Like being buried in an avalanche; there is no up or down. He’s in a white-out – the most dangerous blizzard. He sucks in the ice-laden air, fear gripping him. Ice particles get caught in his throat and he coughs. His heart speeds up and, instead of energising him, it drains him. He racks his brain, trying to remember his emergency training. But his mind is as blank as the landscape.

Think, you fucking idiot. Think!

It’s pointless shouting. He doesn’t have a two-way radio. Nobody can see or hear him. Christ! What happened? His jaw is chattering, his body wobbling, and now he can’t feel his hands or feet. He lifts his right arm so his hand is in front of his eyes, but it doesn’t feel as if it belongs to him. His fingers won’t flex and the skin is grey, the same colour as his dear mum when he found her dead in her flat. Frostbite and hypothermia have taken hold of him. What he can’t understand is why he isn’t wearing a glove. He checks the left hand. No glove and no watch, either. Nothing makes sense.

Knox attempts to bend his knees. His legs are stiff and movement is painful. He manages to bring them near enough to discover he wears socks, but no boots. The socks are caked in ice and look like snowballs. His shivering is so violent that when he tries to touch them, he topples over.

Stunned by his helplessness, Knox stays where he fell. He places a numb hand on his stomach but he can’t tell if he’s still wearing a coat. He can’t feel anything. He blinks away the ice in his sore eyes and peers down the length of his body. He sees the navy blue of his fleece. No coat. The realisation that he will die if he doesn’t find shelter very soon is like an electric shock and his whole body spasms. Terrified, he scrambles to a sitting position, battling the blizzard and his own weakness.

‘Help!’ he shouts, over and over, oblivious to the pointlessness of doing so.

For the first time since he was a boy, he cries. The tears are blasted by the gale and shoot across his skin and on to the woollen edges of his beanie, where they freeze, as hard and round as ball bearings.

Knox struggles on to his hands and knees like an arthritic dog, sobbing, a long string of snot hanging from his nose. Shelter. Must find shelter. Despite his numb extremities he crawls on all fours, around in a tight circle, hoping to see something, anything that will tell him where there’s a tent or a shipping container. Any kind of shelter. But there are no shapes of any kind. Nothing but whiteness. The desperate man decides to go in one direction for ten steps, then turn to his right for ten, then again and again until he returns to his current position. The gusts are so powerful, it’s pointless trying to stand. So he stays on all fours.

He tells himself that Robert Falcon Scott walked thousands of miles to the South Pole with frozen feet. Then he remembers Scott never made it back. Knox’s head is tucked into his chest and the patches of hair sticking out of his beanie are stiff and white. He peers into the distance every now and again but the view doesn’t change. Where is the rope, for Christ’s sake? When Knox thinks he’s done a full circuit, he stops, but there’s no way of telling if he has returned to his starting point. He pants, exhausted. Perhaps he should build a snow cave, as all deep-fielders are trained to do, but he doesn’t have a shovel or ice axe, and his hands are useless. Suddenly, he feels on fire all over and claws at his fleece, trying to remove it. But he can’t even grip the hem.

Like a match, his strength flares ever so briefly and then vanishes.

He wakes with a start. How long has he been lying here? Minutes? Hours? The snow build-up is now a blanket over him. He pulls his knees to his chest, curling himself painfully into a foetal position.

He chuckles. What a tit! He’s going to get such a ribbing when they find him, lost only a few feet from the camp. He’ll never live it down. Oh well. Story of his life: always the butt of jokes. He isn’t shivering any more and feels warm and cosy. Yushkov will know he’s missing. They’ll be looking for him. He’s so tired. Tired and numb. He can’t hear the wind any more.

When he closes his eyes, everything is peaceful. Knox hears his mother tell him it’ll be all right. She’s reported his bullying to the headmaster. His school blazer is ripped, but she’s not cross. His head in her lap, she brushes his long fringe from his eyes. As long as she keeps holding him, he isn’t afraid.

Kabul, Afghanistan

Olivia Wolfe’s head slams into the passenger window, dislodging the scarf that conceals her Western features, as the dented Toyota Corolla – Kabul’s favourite car – bounces out of a pothole. Hastily covering her head, she fails to notice she is being watched by an old, bearded Mesher in a black turban standing at the roadside, who raises a mobile phone to his ear.

‘Can’t we go any faster?’ she asks Shinwari.

Her driver and translator is a short man still wearing a Saddam Hussein moustache, who waves a hand at the makeshift market stalls bottle-necking the narrow street ahead.

It’s December and snowing. Their progress is slow as they dodge haggling shoppers, bicycles, wooden carts, ancient cars and overburdened, skeletal donkeys. Street vendors in thick coats call out to passers-by, offering pomegranates, eggplants, carrots, cauliflowers, nuts and spices, freshly butchered meat, birds in cages, hot green tea in urns. Cars honk, brakes screech, men shout, chickens squabble. Behind the stalls, ramshackle shops compete for custom. One sign in English and Pashtun, offering a ‘Modern Gym’, is riddled with bullet holes. She’s not surprised; foreigners are not welcome. Snowflakes settle on sand-coloured shattered shops and homes, and the slouching, weary shoulders of a people at war too long. Winter hides the beige city’s wounds. But it does not heal them.

Wolfe spots a woman in a head-to-toe pale blue burqa, accompanied by a man she expects is the husband. This is the first woman she’s seen in the street.

‘Blue Bottle,’ says Shinwari.

He glances at Wolfe and grins, but continues to lean over the steering wheel, as if somehow this will make the car go faster. She’s heard that derogatory term before, back in her foreign correspondent days when she accompanied the allied troops into war. The troops coined the expression ‘Blue Bottle’.

‘Where are all the women?’ she asks.

‘Afraid.’

Accelerating around two boys pushing a bicycle, the horizontal crossbar laden with a bag of wheat they intend to sell, Shinwari then swerves across oncoming traffic to turn left up a mountain road, on either side of which are box-shaped homes that appear to be carved into the sandy hillside. Children pick through the rubbish littering the slopes below.

‘I don’t like this,’ Shinwari says. ‘One road in and one road out. Very dangerous.’

Her ‘fixer’ of many years, Shinwari negotiates their way through roadblocks and no-go zones, offering bribery and banter to officials and warlords alike, so she gets her interview. She trusts his judgement but this one is worth the extra risk.

‘I have to do this.’

Shinwari shakes his head. The car lurches and the chassis scrapes across exposed rock. Wolfe fidgets in her seat and clicks the stud of her tongue piercing against her teeth. Earlier on she was freezing – the car’s decrepit heating system gave up the ghost years ago. But now, as her heartbeat quickens, she is stifling in her long brown Afghan dress.

‘Her husband is not there? You are certain?’ Shinwari asks, his voice shaky.

‘He’s in Tajikistan.’

Shinwari peers through the filthy windscreen as he searches for the right address, the lethargic wipers fighting a losing battle.

‘If Ahmad Ghaznavi knows you’ve been asking about him, this could be a trap.’

‘Shinwari.’ She turns to face him. ‘I know what I’m doing. You know that, right?’

‘Yes, yes,’ he replies.

‘Going after Colonel Lalzad was just as dangerous. We exposed him for the torturer and killer he is. That’s why he’s now in a British gaol. Because of us.’ She squeezes his shoulder. ‘But he’s still running his organisation from prison and word is the drugs are funding an Isil terror cell in the UK.’

‘So why you see Ghaznavi’s wife?’

‘Ghaznavi is Lalzad’s right-hand man in Kabul. He gets the drugs to England. Nooria Zia says she knows how the drug money reaches the man behind this British cell and who he is.’

Shinwari’s forehead is slick with sweat. ‘But why does she help you?’

‘She hates him. He raped her at fourteen. When she went to the police, she was convicted of the moral crime of being raped. Had his son in Kabul’s Women’s Prison. I did a story, remember? You got me the interview.’

‘Yes, yes, but this is big risk for her.’

‘Let me finish. Ghaznavi’s first wife only gave him daughters, so he pressured Nooria into marrying him, legitimising his son. She wants to be free of him.’

Shinwari nods his understanding and focuses on the narrow road. A hairpin bend. Fewer houses. A steeper climb.

‘You always thank me,’ he says. ‘Other journalists, they use me and leave. I thank you.’

‘Any time, mate.’

He scans the street. The houses are bigger, better built.

‘That one,’ Shinwari says, nodding at a mansion that is about as out of place as exposed cleavage is in Afghanistan.

‘A poppy palace. Of course,’ Wolfe says.

Shinwari whistles through his teeth.

There is an eight-foot-high perimeter wall, freshly painted cream, and a wrought iron gate, painted gold. Behind the wall, the house façade is dominated by six wide cream columns, the capitals at the top in gold and shaped like scrolls. These support three semi-circular balconies and the floor above. Through vast sliding doors, Wolfe can see a chandelier hanging from the ceiling. The rooftop is flat, supporting a large satellite dish, and is surrounded by a waist-high wall from which to admire the view or shoot intruders.

‘I’ll turn the car around. Make our exit faster.’

Wolfe tucks wisps of her raven black bob under her scarf, then taps the deep pockets of her loose dress. In one is her smartphone. She’ll record the interview with it. In the other is a long key-chain that holds keys to her hotel room, home, motorbike and a locker at Kabul Airport. She doesn’t wear glasses – the sign of a foreigner – and her other body piercings are well hidden. Only her small black field pack strapped tightly to her back suggests she’s not a local. The bag usually contains her laptop, sat phone and spare battery, power adaptor, a few items of clothing and a toiletries bag, all of which she left in the airport locker to save weight and bulk. But the backpack stays with her. Always. Attached to it by a clip is a metal water bottle with a long neck and screw-in plastic stopper. Her money and passport are hidden in a money belt beneath her dress. Earlier, Shinwari had asked her why she wore an almost empty pack.

‘Protection,’ she’d replied.

The house opposite Ghaznavi’s is unfinished, the upper level exposed concrete breeze blocks. Another poppy palace. Shinwari parks outside. Wolfe switches on her smartphone’s video recorder but leaves it in her deep pocket. Her visit must appear social.

‘Let’s go,’ says Wolfe, getting out of the car.

She waits for Shinwari, then walks a few steps behind him. He tries the golden gate but it’s locked. To his left he finds a bell to press. They stay silent and wait. Through the gate’s swirling ironwork, Wolfe sees a carved wooden door open. She tenses, ready to run. It is not Ghaznavi or his armed guards who step on to the porch, but a young woman in a pale pink silk dress embroidered with golden flowers, with a simple black muslin scarf over her head. She hesitates and scans the street, then hurries to unlock the gate, opening it a fraction. Nooria looks at Wolfe, her jade green eyes wide with panic. Wolfe stares at the face of a frightened child.

‘You must leave,’ Nooria says, her accent thick. ‘Mina is watching.’ Ghaznavi’s first wife.

‘Can you meet us at the market later?’ Wolfe asks.

She shakes her head.

There is a loud crack that seems to echo down the mountainside. Something zips past Wolfe’s cheek. Nooria jolts, eyes wide, as blood spurts from a hole in her neck. She collapses backwards.

Wolfe throws herself at a stunned Shinwari and they hit the ground hard. ‘On the roof opposite,’ she pants. ‘Sniper.’

She crawls to Nooria. The girl blinks rapidly in shock, blood pulsing from the wound.

‘Help me!’ Wolfe calls to Shinwari, but he’s frozen with fear.

She grips Nooria under the armpits and drags her behind a column. Wolfe uses the girl’s scarf to try to stem the blood flow.

Shinwari scuttles after her. ‘What do we do?’ he says, cringing behind the pillar.

‘Kabir . . .’ says Nooria, her voice a gurgle as if she’s drowning. Foamy blood seeps from her mouth. ‘Kabir Khan.’ She chokes.

‘Nooria!’

‘Bomb London.’ The girl’s voice dies away then, in one final act of defiance, she spits out the word, ‘Da’ish.’ The Arabic acronym for Isil or Islamic State.

Another shot booms out. No silencer. The bullet thuds into the snow only centimetres from the column they hide behind. Nooria stares vacantly at the sky. A snowflake lands in her right eye and melts away into a tear.

Wolfe searches for an escape route but the thirty feet between them and their car might as well be thirty miles. There is no cover.

‘We gotta run for it,’ she whispers.

Shinwari doesn’t respond. She shakes his shoulder.

‘You hear me? No choice. We run for the car. You understand?’

‘Yes.’ He’s as pale as the murdered girl.

Wolfe peers at the uncompleted roof where she thinks the shooter has set up position. No movement. No glint of metal or scope. She unclips her backpack waistband, wriggles the straps off her shoulders and clutches it close to her chest.

‘Car key,’ she says.

Shinwari gives it to her, hand trembling. Thwack. A bullet narrowly misses his right shoulder. He recoils.

Ghaznavi doesn’t want us to leave, Wolfe thinks. The sniper could have killed them by now. They’ll make good hostages for a high ransom.

‘Ready?’

He nods.

‘Me first. Stay right behind me. Okay, now!’

Wolfe jumps up, positioning the backpack so that it shields her head and heart. Sewn into the pack is an ESAPI plate designed to protect the body from small arms fire. With Shinwari so close, it gives some protection to both of them. She darts towards the car. But no gunshots. Slipping on some ice, she stumbles and Shinwari literally picks her up by the back of her dress and shoves her forward. They make it to the Corolla and duck low, hoping the sniper’s sightline is blocked. Wolfe shoves the key in the driver’s door and turns it, just as she is yanked back by two men with Kalashnikovs over their shoulders. Her backpack falls to the ground. One of them grabs it. The other grabs her. She lashes out with her boots as she is dragged backwards, but his grip doesn’t loosen, impervious to her blows.

‘Get help!’ she yells at Shinwari, who is cowering by the car.

Her captor, in a brown coat and dirty white turban, shoves a hand over her mouth. She gags at the smell of tobacco and shit on his fingers. Her heart races and panic threatens, but if she is to get out of this alive, she must think. Every instinct tells her to keep struggling, but her training tells her she’s wasting energy. As the gates to Ghaznavi’s mansion are locked, Wolfe is dragged further into the compound, her heels sliding through a pool of Nooria’s blood. She needs a plan, and to plan she must clear her mind. She shuts her eyes and focuses on calming her heart rate. On the other side of the wall, the Corolla’s engine screeches into life and the tyres skid as Shinwari tears off down the road. They’ll expect her to be paralysed with terror or weep or beg. Playing the weak female gives her an advantage. She goes limp, surrendering.

They stand her up and give her a shove. Wolfe opens her eyes, taking in her situation: three men, a locked gate and no weapon. Her bag and sat phone are held by the second man with a Kalashnikov, who has the gate keys hanging round his neck. Taller and younger than her brown-coated assailant, he runs a tongue over his thin lips. Both armed men point their guns at her torso. The third man is scrutinising the inside of her bag. He drops it to the ground, then turns to look at her. She recognises Ahmad Ghaznavi. His black beard and hair are trimmed short, Western style. He is dressed head to toe in a long white shirt and white baggy pants. His tasselled loafers are Italian, his watch a gold Rolex.

‘You killed your wife,’ Wolfe says, trying to keep her voice level.

‘She betrayed me. And you, you will make me even richer,’ Ghaznavi says. ‘Your newspaper will pay well, I am sure.’

‘Shinwari will get the police.’

‘I own the police.’

He says something in Pashto to his men. The only word Wolfe understands is ‘whore’. Ghaznavi turns his back on her and walks up the steps to enter his house. She glimpses a woman, her face hidden by a veil, who follows him down the hall in silence. Somebody closes the front door.

Wolfe checks the rooftop and upstairs windows, but it seems they are not being watched. Her captors lean their rifles against the wall. They laugh and jeer at her. She is their reward. The taller man is playing with his crotch, taunting her with what he will do, as the one in the brown coat laughs, revealing some missing front teeth. Wolfe lifts her left hand up, palm facing outwards, and says in Pashto, ‘Let me go in peace.’

There are key phrases she always learns in the language of any country she visits. This is one. Another is, Help me, I need a doctor.

Her right hand is in her dress pocket, gripping her key-chain: a thick cable as long as her forearm, her keys on a ring at the end. She casually pulls it from her pocket. All the while she has her other hand out in front to distract her captors. To them she is saying: back off!

The taller man steps closer, arms wide as if to grab her. Wolfe swings the cable back, then up and over, like a fast bowler, and lunges forward so the sharp keys smack him hard in the side of his face, gouging a deep wound under his eye. He yelps; his hand shooting up to the wound. In one continuous motion, she swings the chain in an upwards arc so the keys collide with his mouth, slicing through his lower lip. His head jolts back. Lifting her leg, she bends her knee and kicks out, the tip of her steel-toe work boot smashing into his balls. He crumples to the ground, groaning.

The brown-coated man is so stunned he fails to react immediately. Then he charges. Wolfe swings the keys at him but isn’t quick enough. He grabs her raised wrist with one hand and punches her in the face with the other. She stumbles, reeling from the pain, and lands on the icy ground. He yanks the key-chain from her hand and tosses it away. Disoriented, she scrambles to her knees and blinks away the dizzying light in her eyes. She needs another weapon.

Wolfe pounces on her discarded backpack, unhooks her metal water bottle and grips it by its elongated neck. Her attacker has the advantage: he stands; she is on all fours. He looms over her, shouting abuse, and spits on her. Then, eyes down, he fumbles for his penis. She jumps up and, in a whipping motion, strikes him on the jaw. He sinks to his knees like a lame horse. With all her strength she slams the metal cylinder into the side of his head, the blow propelling him sideways on to the ice. Spreadeagled, he doesn’t move.

But it’s not over. Her other assailant struggles to get up, still clutching his crotch. Wolfe kicks him in the throat and yanks the gate keys from around his neck, snatches her pack, staggers to the gate, unlocks it and runs.

Someone yells out. ‘Here! Olivia!’

Dazed, she follows the sound of the car engine and the cloud of hot exhaust. She sees Shinwari’s head sticking out of the window. He’s come back for her. Yanking open the back door, she throws herself on the seat to the rapid rattle of Kalashnikov fire.

‘Drive!’

London, England

A man in his seventies wearing a Barbour coat and corduroys, trailing an overfed Jack Russell, passes me without so much as a glance. Like London’s ocean of homeless, I have become invisible. I dress to disappear. My only distinguishing feature – scarring around an eye – is partially concealed behind thick-framed glasses and, today, by the hood of my nondescript, black pea coat, pulled tight. I am no threat. A student? Unemployed? Who else would be crazy enough to sip tea on a park bench on a bone-chilling weekday morning like this?

The dog charges behind the bench, its piercing yap doing my head in as it peers up into the bare branches of a horse chestnut. Conkerless and leafless, the tree resembles an umbrella, fabric torn, spokes broken. The old fella dutifully follows, cur

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...