- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

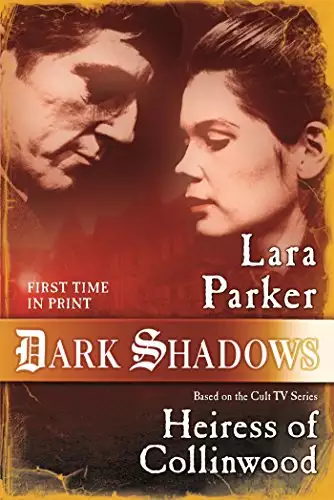

Dark Shadows: Heiress of Collinwood is the continuing the story of the classic TV show, Dark Shadows by series star, Lara Parker.

“My name is Victoria Winters, and my journey continues . . . .”

An orphan with no knowledge of her origins, Victoria Winters first came to the great house of Collinwood as a Governess. It didn’t take long for the Collins family’s many buried secrets, haunted history, and rivalries with evil forces to catch up to Victoria and cast the newcomer adrift in time, trapped between life and death.

At last returned to the present, Victoria is called back to Collinwood by a mysterious letter. Hoping to fill in the gaps of her memories by meeting with the people who knew her best, Victoria returns to the aging mansion. However, she soon discovers that the entire Collins family is missing—except for Barnabas Collins, a vampire whose own dark curse is well known. Victoria discovers that she has been named sole heir to the estate, if only she can prove her own identity.

Beset by danger and dire warnings, Victoria must discover what dread fate has befallen Collinwood, even as she finally uncovers a shocking truth long hidden in the shadows . . .

At the Publisher's request, this title is being sold without Digital Rights Management Software (DRM) applied.

Release date: November 8, 2016

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Dark Shadows: Heiress of Collinwood

Lara Parker

Collinsport, 1797

Even though I had promised Peter never to leave the cottage without him by my side, nor to wander into the village alone—people were still suspicious and many persisted in the belief that I was the witch—that afternoon I found myself in the woods on the other side of the stream from the gypsy camp, peering through the trees and trying to get a glimpse of the settling in.

I had heard the wagons passing before dawn, the snorts of the tired horses whose hooves had been padded with straw, and the squeaking of wheels in the ruts. I crept to the window and pushed open the shutter to watch the vardoes with their rounded roofs lumber down the road like giant snails silhouetted against the brightening sky.

Peter woke and mumbled into his pillow, “Stay away from the commons, Victoria. Those wretched people are not to be trusted.”

I withdrew and closed the latch thinking I should heed his words, but there was so little excitement in sleepy Collinsport, a fishing village where the only topic of conversation was whether the sea was calm or violent, or who had drowned in the last storm. Watching the caravan pass in the mist had flushed a longing in me to catch sight of the earliest gypsies, to see how they managed, these roaming travelers who called no country their own. I thought I would only observe them from a distance, and I would be back in my kitchen before dark.

The day was warm and windy with thin streaks of cloud painted across the sky, and I breathed in the rank odor of the marsh as I made my way out of the woods and across a field of tall grass stitched like an enormous quilt with blue asters, ox-eye daises, and Queen Anne’s lace. Summer had come at last with its butterflies and bees, but it had not lifted my spirits, nor had it dried up the bog at the edges of the stream. My ruined boots sucked in the mud and the hem of my skirt grew soggy from the damp.

I picked a handful of wildflowers to form a bouquet, but soon let them drop, thinking they would wilt in the heat before I carried them home. Upon reaching the stream I had begun to wade through it when melodious morning birdsong was disturbed by the harsh cawing of ravens, and I looked up to see a flock spiraling, drawn perhaps by the promise of discarded food. The gypsies, who cooked on fires and ate out of doors, were known for scattering their garbage in the grass.

I heard a dog bark, a man’s voice cry out, and the ringing of an ax before I came over the rise, but I was disappointed when I looked down at the field.

The camp was smaller than I had expected, and although the ground was already bruised by the gypsies tramping about, there was only a handful of clumsy wagons drawn into a circle. I had been anticipating the sort of pageantry I had seen in my own time when the Roma came to Collinsport every summer, a kaleidoscope of vibrant colors like a Bruegel painting with all the music and wild dancing, and of course, the gypsy horses. These tired steeds had sunken necks and heads that drooped low, and the encampment resembled a squalid hamlet, one that might lie outside castle walls, the dingy sites like piles of wet leaves in the bright green grass.

The people I saw milling among the wagons were dark skinned and roughly clad, and the many children were near to naked, their clothes little more than rags. I had forgotten that I was now living in the year 1797, long before the great diaspora of gypsies from Eastern Europe, and the bands sent to America before that time had been the shunned and despised. As I drew nearer and looked down at the disheveled tribe, I tried to remember what I had learned about their history. I knew they had struggled to maintain their traditions, and that the earliest gypsies were outcasts and drifters. Didn’t Napoleon ship gypsies to Louisiana before he sold the territory to the United States, just to be rid of French convicts? I wondered if these I saw before me were the same sort.

The black ravens careened in the sky riding a gyre, and I shivered to hear their echoing caws, like an omen from a world beyond the clouds. Were their cautions for me, I wondered, wandering so far from home and safety? I had a fleeting thought that I should return at once, but a cool breeze traveled over the meadow like a benediction, and instead I hesitated on the hillside and watched the gypsies unload their wagons.

They had such possessions! I was reminded of the homeless I had seen on the streets of New York when I had been living there, all their diverse and mismatched valuables piled into a shopping cart. Women tugged pillows and flowered quilts out of the wagons to air them in the sun, and the timbre of tin pots and kettles clattered on the breeze, along with the shouts of children. An old grandfather dragged an armload of kindling from the copse. A youth hung axes and knives from his wagon’s rack. Worn leather harnesses were drying on the tops of the wagons, boots and trousers were strewn in the grass, and a fire or two lifted a smoky halo in the morning air.

For some reason I was drawn to these nomadic peasants who would have their own songs and dialects, their own rituals and demons. As I watched the life of the camp unfolding, I thought they might seem uncivilized, but they were enticingly picturesque, people who rejected ordinary social conventions in exchange for the open road, and I found myself envying them. What would it be like to be so free? My curiosity stirred, I crept down the hill toward the wagons. I knew I was being reckless, and I told myself that if I saw anyone from the village, I would leave at once.

When I entered the camp I felt oddly inconspicuous. I knew the Roma were secretive and distrustful of strangers, and as all the new arrivals had tasks to occupy them, no one seemed to notice me. Voices rang out and their speech baffled me; their dialect seemed to be more from India than from Spain or Hungary. I felt that I was a stranger walking through some foreign village unable to understand the customs or speak the language. At first I wondered briefly whether I was invisible, a nagging worry since I had returned to the past, but I was relieved to see proof that I was corporeal, my footprints in the mud and my shadow trailing me in the sunlit grass.

However, when I glanced around, I was disturbed to see that there were, in fact, a few older villagers who had come to visit the gypsy camp, perhaps as curious as I was, none who knew me, but I recognized them by their farmer’s overalls. I moved away, hoping I wouldn’t be noticed, and wandered in among the wagons. There I began to sense a mood of vitality and comradeship.

Two young boys cried out, “Gaja!” and one tried to grab my skirt before they ran away. A young mother seated on the back step of her wagon hummed an atonal melody in a high keening voice, and cradled a small child in her arms. She lowered the shoulder of her blouse and nestled her breast inside the little mouth while giving me a secretive smile. A very old man with a gray beard, leaning against a tree and smoking a clay pipe, nodded to me just as I heard the tinny sound of a guitar. I turned toward the music and I saw seated in a wagon a middle-aged man in a slouched cap who leaned over his instrument. He, too, smiled, flashing white teeth, and near him, a very old woman pulled a clothesline between two trees and frowned at me as her faded blanket flapped in her face.

Then I did see a man I recognized and I felt a stab of fear. He was talking with several farmers from the village who were unfamiliar, but his face was one I thought I knew. They were haggling with a tinker over some copper cups, and the gypsy had poured rum in them as proof of their worth. Did he give me a mean look from under his eyebrows as he took a sip?

I turned my back and almost tripped over a large pot tended by two women in long ruffled skirts. It steamed with a thick broth where lumps of some root vegetable swam, and I inhaled a spicy odor. I hesitated because the two boys who had teased me had returned with a dead muskrat, and collapsing on the ground beside the women, began to skin it. I was amazed to see the skill with which they slit the stomach, and with filthy fingers and fierce jerks, peeled back the fur. Then, placing it on a stone, one of the boys removed the entrails while another dismembered the muskrat’s naked torso. All the pieces went into the pot except for a handful of innards thrown to a yellow dog who wolfed them down eagerly.

The longer I remained at the camp the more painful was the weight in my heart. Compared to the cheerful atmosphere, my own life seemed stagnant and colorless, and although the gypsy camp was destitute, it was as if a circus had come to town. I was an outsider with no true community, and the gypsies seemed bound together as one large family. As I watched them, hypnotized by their industry, an unexpected urge to crawl into one of the vardoes took hold of me, and leaving the farmers on the far side of the wagons, I sat down on a fallen log and drew my shawl over my hair.

There, as was my wont, I fell into a reverie, contemplating my predicament, and my gaze fell upon a discarded melon rind that had already attracted a swarm of yellow jackets feasting on the orange flesh. With an embittered heart I was reminded of the narrow-minded villagers whose bigotry and intolerance had stolen my freedom and for the hundredth time I thought what a mistake I had made to follow Peter Bradford back into the past.

He had warned me, “Marry me, and you will be marrying a corpse,” but stubborn as I was, I had ignored his protestations. “I cannot live without you,” I had wailed, caught in the throes of love.

Now I knew I did not belong in Collinsport in 1797, any more than I had the first time I had appeared here. It had been after the séance at Collinwood when the family had gathered around a table and attempted to contact the ghost of young Sarah. They were distressed because she had been appearing to David in the woods, and the family believed she was trying to reach them from the past—nearly two hundred years earlier. With painful clarity I remembered that ill-fated evening.

I had been drawn into the circle as a mere spectator with no part in the plan. As always, I was on the sidelines, an anxious member of the audience. Fingertips touching, candles flickering, Roger had evoked the spirits. And unexpectedly, I had been the one whisked magically—and disastrously—back to 1795. There, trapped in an age of ignorance and religious fervor, my modern ways had aroused suspicion, and I had been called a witch. I had been helpless to dispute the charge, and in spite of Peter’s devotion, his skills, and his valiant efforts to defend me, I had been sent to the scaffold. It was my death, agonizing and terrifying, that released me from the spell cast by the séance and thrust me back to my own time.

There a new life awaited me! I left Collinwood to seek employment and began a fascinating new career in Bangor, Maine. I became a diligent working girl dressed in trim business suits, my hair pulled into a bun, an eager smile on my face. For a while I was busy and happy, delighting in my independence, savoring the taste of freedom.

But I was also lonely, and at night I pined for Peter’s affection. For some reason I no longer understood, I fastened my heart to the idea of becoming his wife, an impossible dream, as he lived in another place and time. I fantasized a miracle, as in Brigadoon, but it was only the whimsy of a romantic girl. And then, through my discovery of an enchanted watch that had belonged to him, my wish came true! Longing for my champion spun a thread strong enough to pull me back into his world, and he came for me through the fog of centuries and drew me into his arms.

But, as in any fairy tale, not without a price.

In small towns, superstitions do not die, and the malicious buzzing was like that of a busy hive. A hive of yellow jackets with lethal stings, I thought, as I looked over at the discarded melon and watched the insects devour the soft flesh, digging for the green rind. They were unrelenting and merciless. When I shook my shawl at them, they flew away, but soon they returned, fiercer than ever. Soon the melon would be stripped of its fragrance and its juice.

I shivered. Still in danger of being accused of witchcraft, I was trapped in a closeted dwelling, a small cottage outside of the village. Boredom bewildered me, every day was like the one before, and my tasks were menial and repetitive. I was ashamed of my restlessness, but the monotony made me want to scream inside. I hungered for a fuller life, something more vital and challenging, my talents exercised, my mild-mannered personality enlivened in a busier, more bustling world. I remembered my time in Bangor and my new and exciting responsibilities with a wistful nostalgia. I knew there must be dreamers, poets, architects of fate, and I longed to live among them, but they were not here in Collinsport in 1797.

I also knew, outside of town, along the cliff that fell to the sea, there was a grand mansion with lives and loves within, but I was loath to return there, not knowing what I would discover or if they would even allow me to enter. In my own time I had been the governess there, a brash young boy in my charge, and I had been well cared for. But they only knew me now in this era as the Collinsport witch who had caused heartbreak and havoc.

I found myself remembering that last night at Collinwood, before I fled to Peter and the past, before I became a phantom—for that must be what I was now—when still a flesh-and-blood woman, I had received and turned a cold heart to a disturbing proposal of marriage from Barnabas Collins.

Once again I wondered what sort of marriage would that have been, wed to a supernatural creature. I had rejected my tormented suitor believing that I loved Peter Bradford more than life, and now I was haunted by my decision, just as I was tortured by the memory of the vampire’s anguished entreaty, his fierce gaze, his hands gently sliding up my back, and his lips beneath my hair. I knew I should feel guilty for calling up these memories, but as they were only vague reminiscences, I gave them leave.

These days, forbidden to wander about, expected to remain an obedient wife, I spent many hours staring out the window at a garden full of weeds where all that flourished in that barren plot were jumbled and confused regrets. Again and again I suffered my moments on the scaffold, my throat twisted on fire. How had I survived? It was still a mystery, and all I knew was some poor woman had taken my place. I had returned magically to the twentieth century, and I had a strong recollection of a move to Bangor and an exciting job as a news reporter. This seemed a dream now, impossible to contemplate. Why had I thrown away a life of independence and self-respect? All that had come to an end when I was sucked into the vortex of centuries gone by, and back into Peter’s arms. I still had no idea how it had happened, only that I had died. And lived again.

But nothing had prepared me for a solitary life of mending rough baskets, knitting socks, churning butter, or stirring porridge over a fire—no familiar culture to embrace me, no mother or sister to train me, or neighbor to instruct me. It was not the hard work that I minded—I was used to kitchen chores from my time at the orphanage—but the dreary, uneventful days. Peter’s promise to take me to Boston was never mentioned, and moving west had become a forgotten dream. I was left alone in the cottage while Peter went off to work in his small law office, defending farmers and tradesmen, just as he had defended me. I knew he worked hard, and because he said it was all for us, for the hundredth time I thought how selfish I was to be dissatisfied.

I heard the shouts of children and, coming back to the world around me, I shook off my ennui, and I became aware of the now-bustling encampment. I rose and wandered again through the wagons, where I watched older women peeling potatoes in their laps and tending the cooking pots. Some were even chopping wood. Smoke rose from the fires, and I could taste a tangy odor in the air. Among the drab and dusty garments I began to see flowered skirts, vibrant colors, and a sprinkling of gold coins. Children raced after a dog—gleaming smiles in their smudged faces—and played with a stick and a rock, or waded in the mud. Two toddlers chased a bedraggled rooster under a wagon, but it turned on them with its sharp spurs and sent them squealing.

Then for the first time I felt eyes upon me. I recognized the same man I had seen earlier, staring at me through the space between two wagons. His cap was pulled down over his forehead, but there was menace in his eyes, and the moment I saw him looking at me a chill crept up my spine. I thought it must be Edward Wicks, the brother of the poor girl who had died on the scaffold in my place. Even though I had not chosen her fate or mine, I knew he might wish me ill, and I turned away quickly before I met his gaze and crossed back into the camp shaking off a sense of foreboding.

I knew it was past time for me to slip away for home.

Then I saw a small group had gathered in the cleared area between the wagons, and I eased among them, my eyes cast down, my shawl over my hair. I was reassuring myself that, in truth, I should have nothing to fear from Edward Wicks, when I heard the crowd murmur in astonishment and someone cry out, “Aye, hoop-la!”

I gasped when I saw, at the center of the gathering, the strangest sight—a man with an enormous dancing bear. Yellow-furred and muzzled, it rose on its hind legs, stood first on one foot and then the other, and made plaintive moans, shuffling to the beat of a metal tambourine. The bear’s fur was so filthy and matted I thought at first it must be a man in a bear’s suit, its shaggy coat loose on its bones, its stomach sagging. But when two children ran up to it and poked it in the belly, it swung its great head back and forth and growled, and I saw from shriveled tits that it was a real bear, a female, old and resigned to her fate. The owner of the bear was a small man who wore a French beret, an embroidered black vest, and baggy trousers, and a small clay pipe was clenched between his grinning teeth. He wielded a heavy stick in the air, banged the tambourine, called out, “Hoop-la!” when the animal began to falter, and the crowd cheered. I was transfixed and I could not look away from the bear. How did her owner make her perform, I wondered. Why did she obey him when she was larger and stronger?

Then I heard fiddle music, and I was drawn to the sound. Unexpectedly, a wave of resentment flowed through me, and with a flash of obstinacy, I thought I had as much right as any to delight in the merriment of the gypsy camp and wander freely in the midst of foreign attractions. I was not a prisoner, nor was I obligated to remain sequestered in a cabin when life outside my door brimmed over with such sweet enchantments.

Seated on the step of one of the wagons was an old man with a violin, and the tune he played was coaxed from the heart. He nestled an instrument so frail it seemed to be made of paper under his grizzled chin. Many people from the village had gathered around, and the musician’s painful expression suggested a lifetime of suffering. Tears streaming, he drew his bow across the strings, and one high mournful note vibrated in the air like the song of a bird at dawn.

Then, after the crowd grew silent, holding its breath, he broke into a rollicking melody and to my surprise the camp came to life! Other makeshift tambourines appeared, a tin drum, and even a dilapidated piano on the back of a wagon. Two girls began to twirl, their skirts twisting and flowing, and as I watched and wished I could join them, a young boy grabbed my hand and pulled me to the center of the melee. I tried to refuse, but the violin scratched out a seductive rhythm, a joyful tune hard to resist; bodies swirled around me, and standing motionless seemed more conspicuous than joining in, and so I began to spin. Soon I was sweating, free and alive for the first time in months, and I saw the admiring eyes of several men watching me as I lifted my arms above my head and swayed, a smile on my lips. I was laughing when something tripped me: I stumbled, and I felt a hand close around my wrist and jerk me backward out of the crowd. I was struggling to keep my balance when I heard a growl in my ear.

“I see you, Victoria Winters. I see you here. You celebrate your good fortune when others grieve.”

My stomach clenched; I jerked away and took off running, frantically ducking in and out of dancing bodies, sick with the knowledge that this was what Peter had warned me could happen. But quick as I was, desperate as I was to get away, he was fast on my heels. He caught me by my skirt, my shawl, and then my hair, and I cried out and almost pitched over before he had me against him and I could smell the sweat beneath his leather and the rum on his breath. I tried to wrench away but his grip was strong, and then he clenched the back of my neck and whispered, “Witch! You took my sister’s life and now you flaunt your beauty in public for all the world to see!”

He dug his fingers into my back, searching for my spine, and I fought to pull loose, but he turned my face to his and then, just as I feared, I was looking into the eyes of Edward Wicks.

“How dare you dance,” he hissed at me.

“Please … you are hurting me.”

His voice was low and raspy. “Aye, I will hurt you,” he said, and he took a ragged breath, his mouth twisted and his eyes blazing, “and I will kill you if I like. She was an innocent girl who never harmed a soul.”

My head fell forward, and he backed away, leaving me bowed. The music had stopped and the crowd was silent, all watching me. I stared at my feet, trembling, my heart racing.

“I’m sorry,” I muttered, thinking he had a right to his anger. “I don’t know how it happened.”

“You were led to the gallows, witch that you are.”

“No, that I am not.”

“The cowl was drawn over your head … I was there, I remember … because I lusted for you, such a beauty you were, and I was pained to see you die.”

“Please, listen to me—I was not the witch…”

“The trap was sprung and you dangled, feet twitching until you moved no more. The crowd cheered but you were not there to hear it.” He jerked my arm. “Or were you?”

I raised my head and looked him in the eye, seeing his pain but believing I did not deserve this humiliation. “It was not my doing, Edward Wicks.”

Clutching my shoulder he leaned into me and his voice was rough with tears. “But when they lifted you down and pulled away the hood, it was not your black hair that fell about the blue and swollen face of the dead woman. It was my sister’s pale locks.” He turned to the crowd. “Phyllis, my sister, was exchanged, substituted she was, like a surrogate in a play. My simpleminded sister who had done no wrong”—he pointed a finger at me—“died in her place.”

Panic seized me. “Please,” I insisted. “I was amazed as well. I didn’t understand how it happened.”

“Perhaps that is your weakness, Victoria, to understand so little. But I am not moved. You spelled her, you did.”

“No! I did not! It was cruel, I know, but truly I had no part in it. It was a twist of fate—”

I felt the blow before I saw it coming, my head reeled, and the ground came flying up. My face splattered against the dirt, and my mouth filled with grit as the the crowd closed in and voices around me sang in waves.

“Please, help me,” I sobbed, but no one came to my aid. Grim villagers stared down, their expressions more curious than concerned, as though they were watching a play. I tasted blood, and my jaw throbbed with pain. I tried to crawl away but Edward took hold of my foot and dragged me back. He leaned over me and spat in my face. “Harlot! Where did you come from? You know you are not of this place.”

He placed the sole of his boot against my cheek and pressed down. My hands flew out and found his ankle, and then, struggling, I tore at his leg with my nails, but he did not lift off.

“The witch has claws!” he cried, and pressed harder. I knew he intended to kill me. My temple bulged as bright sparks sprang into my eyes. The flickers dimmed, and a blessed darkness flowed.

From far off I heard Peter’s voice calling.

“Victoria!”

* * *

The duel was set for dawn, but when I awakened from a fitful sleep with the sky still dark, the space beside me in the bed was empty and Peter was gone. I dressed in a panic and now, terrified that I would be too late, I stumbled through the corn rows, my skirts gathered into a bundle at my knees and my boots digging into the mud. With an ache in my chest so heavy I could hardly breathe, I cursed the foolishness of manly pride. Papery stalks sliced my bare legs, and the wind whipped my hair into my eyes and blew sand on my tongue.

Blackbirds nesting in the fallen cobs whirled out of the earth and whistled a warning above my head. I glanced up and saw the scrawny red necks of what they were—vultures—and from the stench I knew they had found an animal rotting in the field. The birds wrote the truth in the sky with their black wings. Trailing long flowing feathers they might have been angels, but they were not angels. They had not come to bless but to feed, and they could smell death even before it was there.

Ahead, a jagged line of trees rose against the pale horizon, and the sky threatened daylight. Only yesterday the gypsies had been here, but now they were gone, chased off by the local constable, leaving only muddy scars in the grass. When I reached the edge of the river, I stopped and choked out, “Peter!” But there was no response.

Between the dark trunks of trees on the sandbar I could just make out the two figures facing one another, long-barreled pistols raised to the shoulder in stubborn coercion. At first I wanted to laugh at the cartoonish silhouettes, the wind whipping their coattails and the obstinacy of their postures, so rigid and doomed. A cry burst from my throat again, but it only forced the ache deeper between my ribs. My heart skipped, and as in any dream, my limbs were lethargic and painfully slow to move. Was I visible? Was I even alive, I wondered, when I waded into the water, tugging my heavy skirt while I struggled through the rapids like a crazed animal scrambling for the other shore.

The vultures circled high, dark lazy kites above the trees, and I saw a third man standing between the duelers, all in black with a top hat. Dutifully, he sliced his arm through the air. With a desperate lunge I pitched forward, fell at the feet of the man in the cream-colored leggings, and finding my voice, I wailed, “Stop! Don’t do this! Peter! Stop, please!” I turned back to look just as fire plumed from the mouth of his assailant’s pistol.

There was a searing pain in my shoulder and my vision clouded as I fell to the ground, but Peter was already stretched out beneath me. The bullet had found us both, passed through me as though I had not been there, and lodged in his chest. His eyes were glazed, and his lips trembled as he tried to speak. I pulled myself up to cradle his head in my lap and wept, feeling the fullness of my love, my tears falling on his flushed face, and I could not tell whose warm blood pooled beneath us.

I wiped his cheeks and kissed him. “Peter, don’t leave me. Please … not yet. Stay with me.” But I was staring into a mask of graying clay. Heart aching, I watched the light in his eyes grow dim, then fade to darkness.

A shadow fell across us both and I looked up. Edward’s smile was smug, his mouth a curled slash, his eyes hard and shiny as chestnuts. I bit out words.

“You are nothing less than a murderer.”

He stared down at me with a mixture of contempt and pity that made my throat tighten. “No, Victoria. I even threw my first shot away. It’s you who killed him.”

“How can you say such a thing? I loved him.”

“See to yourself, lass,” he said wearily, setting the butt of his pistol against his thigh. He wiped his sweating face with a soiled sleeve. “You made the promise with your look at the camp. A wicked look it was, and not the first time. You have the dark come hither in you. Don’t deny it.”

“That’s not true.” The words stuck in my throat. “I gave no such look.”

“Even so, Peter raised the quarrel, not I. He set the morn. And so it goes.”

“Because you were going to kill me.”

“And so I will, if I choose. You do not deserve to live.” He leaned over and pried the pistol from Peter’s lifeless grip. It seemed a callous gesture and I made a feeble move to stop him, but he stayed my hand.

“The challenged man selects the weapons,” he said, “and these are mine. Part of a valuable set that belonged to my father, with ivory handles.” I watched him place the pistol in the case with its mate and secure the catch.

I tugged my shawl around my hair and looked away then pressed my hand against my wound. I moaned and kissed Peter’s face. “What shall I do?” I said to no one.

His tone was icy, sober now, not slurred with rum. “Why, come with me.”

Edward held out his hand to raise me up, but bile rose in my throat and I shrank back.

“Witch.” His eyes were hard. “Haven’t I won you?”

He reached for me and hauled me to my feet. Then, an arm ab

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...