Chapter One

“Cut! Cut!” the director Raymond Reynolds yelled. He was a tall, loose-jointed man, who braided his hair into a ponytail at the back of his head. Before meeting him, I didn’t think I had ever seen a man with a braid before, and I couldn’t stop staring at it. In my community only little girls braided their hair, never grown women and certainly never menfolk.

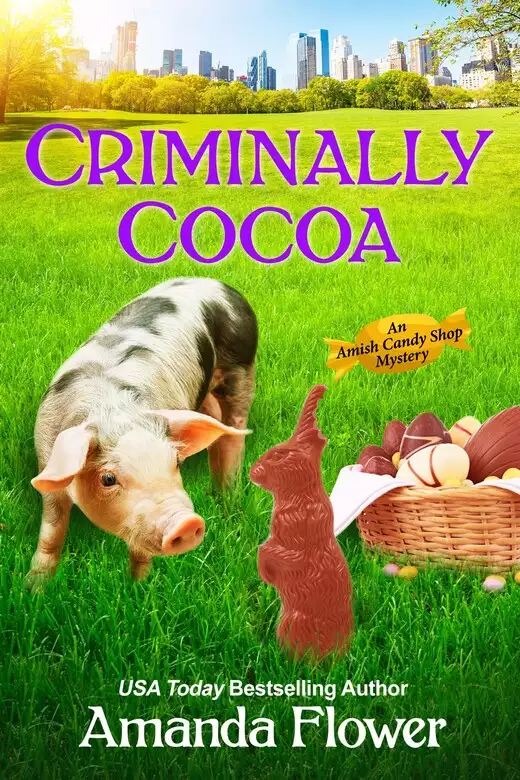

Bailey King froze in place. She was halfway through giving instructions on how to weave a chocolate basket for a candy display. Bailey made tempering the chocolate and weaving it over the bottom of a bowl look easy. She held a strip of chocolate in her hand, and it fell on the top of the almost complete basket.

She was frozen like a doe I had seen once paralyzed by the headlights of my father’s buggy back in Holmes County. Not that we were anywhere close to the rural Ohio village at the moment. We were inside a New York City skyscraper standing on a television soundstage. It was a new world for me, being on a soundstage, also known as a set. I had heard it called both. I have learned so many new words since coming to the Big Apple, which is what Bailey’s friend Cass called the city when we first arrived at the airport. She said to me, “Charlotte Weaver, welcome to the Big Apple!” and I had no idea what she meant. My ears were still ringing and my legs were still be wobbling from being on my first airplane flight, and I thought she’d misspoken until I saw the same phrase all over the souvenirs in the airport gift shop.

Cass had made a big deal out of my coming to New York City because it was my very first time. Bailey lived here before moving to our little Amish village of Harvest. In Harvest, she was an outsider, or at least she was at first—now she fits into the village just fine. I don’t think I would ever fit into the big city, not in my plain dress, with my bright red hair wrapped up into a bun at the nape of my neck and covered with a white prayer cap, sensible black sneakers, and apron. Everywhere we went those first few days, I thought people stopped and stared, but after a week I stopped noticing. There were too many other wonderful things to see in the city, and I wanted to see all of it.

It was this want to know that was the reason I wasn’t baptized into the Amish church yet. Now, during Rumspringa, I could try new things and ask questions. When I was baptized all those questions would have to stop and I would have to live my life by the edicts of the district bishop whether I agreed with him or not. I’d already left my family’s Amish district months ago, so that I could play the organ, an instrument I dearly love. Cousin Clara’s district lets me play music, but they won’t let me avoid making a choice about my faith forever.

Bailey scooped up the piece of chocolate and placed it on a piece of parchment paper. Her long dark hair, which was curled and styled for the camera, fell into her eyes.

The set was almost identical to Swissmen Sweets’ kitchen back in Harvest, except for a few “additional things” to make it seem more Amish—or at least what the Englischers from the network considered Amish. For one, there was a blank-faced doll on the shelf next to the spices. Clara King, Bailey’s grandmother, would never keep such an item in her working kitchen, and Bailey told the producer so. My maam would never have done such a thing either. The kitchen wasn’t the place for dolls. Dolls were for little girls to play with quietly out of the sight of their mother, who would be busily preparing supper to feed ten people. Feeding everyone every night after a long day working on the farm was a production, and my mother didn’t like the children under her feet.

None of this mattered to Linc Baggins, the show’s executive producer. He wanted things called “props” to give the set an Amish feel. I was learning that how the set “felt” was very important to everyone who worked on the show. Before this, I had never thought about what a room felt like at all.

“We have to do something to indicate this is an Amish show,” Linc had argued with Bailey. It was all quite fascinating, really, learning so much about the Englisch world. What’s more, I was gaining insight into what the Englischers thought of us. For one, they all believe that every Amish person lives on a farm. A lot of them do, but certainly not all. I grew up on a farm, but many Amish live in town and run shops, like Cousin Clara, or work in a factory. With land scarce, owning a farm in Holmes County was quite a feat for an Amish or Englisch family.

As strange as my ways were to the New Yorkers, their ways were even stranger to me. For a girl who had never set foot outside of Ohio, everything about this production was like a trip to another planet. I knew very well that I was in the same country as I always was, but the lights and noises and even the smells were so different that it drove me to distraction. At home, the most noise you would hear was the moo of a cow that might have escaped from a neighboring farm. With all the noise and activity in New York, I didn’t know whether most of the people living here would even notice if a cow started walking down the street.

The set was only half of the room that I was in. The other half was where most of the people were. It had a concrete floor, metal fixtures, and uncomfortable folding chairs that didn’t invite you to sit at all.

Three cameras were pointed at Bailey; one was on a track and moved every few minutes. Two other smaller cameras were placed on tripods. Teven, the cameraman, blew his uneven bangs out of his eyes every few seconds, and the light brown strands dangled in the air for a moment like pieces of thread. It made me wonder why he would grow his hair that way when it so obviously annoyed him. I’m sure it was for fashion reasons, something that my Amish sensibilities couldn’t quite grasp. I was raised to appreciate practical and plain dress.

Linc clapped his large hands together, and they made a thwack, thwack, thwack echo off the mock walls of the set. His clapping jarred Bailey out of her stupor, and she carefully picked up the piece of chocolate she’d placed on the parchment. “That was marvelous. You got it just right on the first take, Bailey. You are a natural! We aren’t going to need the entire six weeks to film if things go so famously well.”

Bailey blushed, and her bright blue eyes, so like her grandmother’s, my cousin Clara’s, sparkled. She looked as happy as I have ever seen her back in Harvest. She was one of the best candy makers in the world. I don’t know enough candy makers to make such a judgment, but Jean Pierre, her mentor, told me so last night, and since he had a chocolate shop named after him in this big city, I guessed that he was in a position to know. Even if Bailey wasn’t so good with candy and chocolate, I could see why she would be on television. She was pretty. Everyone back in Harvest, Ohio, thought so, Amish and Englisch alike, especially Deputy Aiden Brody, her boyfriend. Aiden was smitten with Bailey because of her brains and her beauty. Bailey had helped Aiden . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved