- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

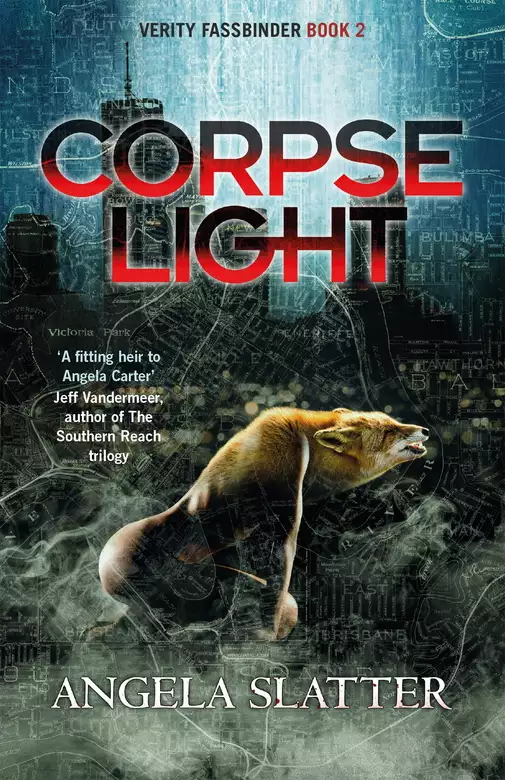

Watch out, Harry Dresden, Kinsey Milhone and Mercy Thompson: there's a new kick-ass guardian in town and Verity Fassbinder's taking no nonsense from anyone, not even the fox-spirit assassins who are invading Brisbane in this fast-paced sequel to VIGIL. Life in Brisbane is never simple for those who walk between the worlds. Verity's all about protecting her city, but right now that's mostly running surveillance and handling the less exciting cases for the Weyrd Council - after all, it's hard to chase the bad guys through the streets of Brisbane when you're really, really pregnant. 'Verity is the best thing about the book . . . she's a surly, straight-talking, Doc Marten-wearing punchbag who investigates Weyrd-related crime on behalf of the beleaguered "normal" police' ( SFX) An insurance investigation sounds pretty harmless, even if it is for 'Unusual Happenstance'. That's not usually a clause Normals use - it covers all-purpose hauntings, angry genii loci, ectoplasmic home invasion, demonic possession, that sort of thing - but Susan Beckett's claimed three times in three months. Her house keeps getting inundated with mud, but she's still insisting she doesn't need or want help . . . until the dry-land drownings begin. V's first lead in takes her to Chinatown, where she is confronted by kitsune assassins. But when she suddenly goes into labour, it's clear the fox spirits are not going to be helpful. Corpselight, the sequel to Vigil, is the second book in the Verity Fassbinder series by award-winning author Angela Slatter. 'Simply put: Slatter can write! She forces us to recognise the monsters that are ourselves' Jack Dann, award-winning author.

Release date: August 18, 2020

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Corpselight

Angela Slatter

She took a while getting out of her car, smoothing the workday creases from her Donna Karan suit, collecting her handbag and the briefcase. She jingled the keys before inserting them in the lock of the house’s front door, as if the noise might ward off evil spirits; as if it might let them know she was home and they should disappear now. The hallway looked fine, but the smell hit her before she’d taken a step inside. Had she caused it, she wondered, with her expectation? She shook her head: magical thinking would get her nowhere. Steeling herself, she followed the stench.

Mud.

Again.

It was all over the expensive silk and wool rug at the base of the new rocker-recliner that had replaced the last one: oblongs of insufficiently jellified gunk, almost like footprints but lacking definition. Up close, the odour was even worse. The whole chair wore a thick coat of the same crap – it wasn’t just mud, but oozing filth. Foetid, contaminated liquefied death.

This was the third such occurrence in as many months: always on the same day. The mess was always there when she returned from work; the perpetrator had clearly waited until she’d left, then set about making its point, always in the same spots. None of her precautions had done a damned thing. She’d be having words with that bloody hippy chick at the St Lucia spook shop about her rubbish ingredients.

She couldn’t imagine the insurance company would pay out, not again, even under the Unnatural Happenstance provision.

The first time this had happened she’d been unnerved, even afraid. The second time, she’d been annoyed. Tricks, she’d thought, shitty little tricks. Shitty, spiteful little tricks.

This time, the only thing on her mind was, Fuck you! ‘It’ll take a damned sight more than this,’ she shouted at the empty room, making sure her anger carried her words all through the house.

There was more, of course: the kitchen was awash with brown, slither-marks patterning the linoleum as if a nest of middling-sized snakes had run amok. The biggest puddle was in front of the fridge – well that was new. She picked her way across the floor, stepping on the clean patches, careful not to slip, not to get sludge on her expensive new Nicholas Kirkwood Carnaby Prism pumps.

The handle of the fridge door was pristine; she grasped it and pulled.

There was a moment, one of those frozen seconds when things stand still. In theory, in that moment, there was time to step away, to jump to safety. In reality, the shit-brown rectangle filling the matt-silver Fisher & Paykel quivered and slid out onto the neutral patent leather of her Kirkwoods with an obscene sucking sound, leaving her shin-deep in muck.

Then the doorbell rang.

Chapter One

‘I’ve given this a lot of thought,’ I said, ‘and I’ve come to the conclusion that I can’t go through with it.’

David put an arm around my shoulders – circumnavigating my waist had become more of a challenge than it used to be. ‘Not to be negative or unhelpful, but I don’t think that’s an option any more, V.’

We were slumped on the couch, staring out over the sea of baby-related items we’d just schlepped home from what I prayed was our Last Ever Shopping Trip: a bouncer with an electronic ‘vibrate’ function that my friend Mel, from next door, swore I’d be grateful for; two colourful mobiles to go above the crib because we couldn’t agree on which one to get (a roster system would be in place until the offspring could decide for herself). Bulk supplies of talc, nappies, wet wipes, rash cream and lavender-scented baby rub. Tiny hats, booties and singlets, so small they required four zeros to indicate sizing, all in nice neutral greens and yellows, because once we’d announced we were having a daughter, the pink gifts started arriving thick and fast. To combat princessification we’d bought Lego, Meccano, books from the Mighty Girl reading lists, science experiments and chemistry sets and Tonka trucks, as well as a good sturdy teddy bear. If we’d been stockpiling canned goods and weaponry in the same manner we’d have been called Doomsday preppers, but as it was, we looked like precisely what we were: very nervous expectant first-time parents. David had even gone through the storage shed where we’d put all his stuff that couldn’t fit into my house (once again avoiding having The Discussion about what would eventually happen to said stuff) and emerged triumphantly with the old microscope he’d been given as a boy. He’d polished it till it shone like new and now it sat on a shelf in the library, waiting patiently for our child to be seized by Science. Occasionally we wondered if we might be getting way ahead of ourselves – but we wanted to be organised, ready.

But that was the fun stuff, not what was making me want to back out of the whole baby-having deal.

It was all the un-fun stuff: bottles, sterilisers, a nappy bag big enough for a US Marine to pack her gear in, a pram that required an engineering degree to put together, let alone operate, a changing table with a simply ridiculous number of drawers, a plastic bath, a high chair and not even worst of all, an apparently irony-free potty shaped like Winnie the Pooh’s head. But the thing that had me making for the hills as fast as I could waddle was the breast pump. It looked nasty – I couldn’t imagine trying to attach it to my worst enemy, let alone me. I’m not thick: of course I understood that expressing milk would mean I didn’t have to get up every time the bub needed a night feed – and it would also mean the other parent would have no good excuse not to do it – but still . . . Breast pumps make the iron maiden and the crocodile shears look appealing. The longer I stared at it, the less I liked it.

‘Are you sure? I mean, there’s got to be some kind of voodoo that can—’

‘No voodoo, no hoodoo, no magic around the baby,’ he said severely. ‘Not until Maisie’s older, anyway.’

‘I think I would like a sandwich now.’

‘You just had a sandwich. To be precise, you had two BLTs at that café, and then you ate half of mine.’ But he got up anyway and stepped around the bench into the kitchen.

‘Correction: our daughter had two and a half BLTs. While she’s distracted by digestion, I’d like a sandwich.’

‘I don’t think it works like that. Cheese and vegemite?’

‘Please.’ I rubbed both hands over my five-storey belly. ‘I can’t wait to have soft cheese again. I miss Brie. And Gorgonzola.’

‘I, for one, have not missed the stinky cheese.’

‘You don’t have to eat the stinky cheese.’

‘No, but I do have to kiss you, who eats the stinky cheese.’

‘That’s true. It is in your contract.’

‘There’s a contract—?’

Any possible escalation was thankfully prevented by a knock on the front door. I levered myself upwards. ‘I’ll get it. It’s critical that you finish that important task.’

‘The fate of the world depends on it?’

‘Sure, why not.’

The figure standing on the patio was recognisable only by the wisps of thin ginger hair that stuck up from beyond the pile of items in the bearer’s arms. More pink things: soft toys, little fairy dresses, teeny-tiny ballet jiffies – and not a one was modestly hidden in shopping bags that might suggest actual purchases. I knew if I asked, the answer would be, ‘I know a guy’.

‘Ziggi Hassman, enough with the fudging pink,’ I said, but stood aside to let him in, landing a kiss on his pale cheek as he passed. The eye in the back of his head gave me a wink. I’d removed almost all the wards from my house since the events of last winter, when Brisneyland in general and me in particular had been threatened by an archangel on a crusade, a golem made of garbage, an aggressive vintner and an especially ill-tempered mage, but I was starting to wonder if I should find one designed to ensure no Barbie doll could enter.

‘I couldn’t help it. Look at the shoes – how small are they?’

‘So small. But you’ve got to stop: I’m only having one kid.’ Not to mention that Mel had already pressed upon me all of her daughter Lizzie’s baby cast-offs. We had enough gear to start our own line of black-market babywear.

‘Also, fudging?’

‘Trying to minimise the profanity so my daughter’s first word doesn’t rhyme with “fire truck”.’

After I’d inhaled two sandwiches and Ziggi had dug through the mound of things we’d bought earlier, and after giving the breast pump an especially dubious glance, offering helpful comment on each and every one, he got to the point. ‘So, V, fancy going for a ride?’

‘That’s phrased like a question, but I fear it is not.’ From past experience my chances of bailing were not good, but I still tried, whining, ‘Ziggi, it’s Sunday.’

‘It would be a leisurely drive.’

‘Am I not on maternity leave?’ I fidgeted with the ring David had given me for my birthday a few months ago: a vintage silver band set with a square-cut emerald; it was on a silver chain around my neck at the moment due to pregnancy-related sausage fingers. I’d noticed lately that whenever I didn’t want to do something work-related, I touched the cool metal and stone as if it might somehow get me out of it. So far, it hadn’t worked, but I wasn’t quite prepared to give up yet.

‘Technically, we don’t have maternity leave, what with our jobs being secret, non-Union and all, but you’re still getting paid for a lot of sitting around as far as I can tell.’

I knew he was right. Ziggi and I were employed by the Council of Five, the group which oversaw Brisbane’s Weyrd population, keeping the community’s existence as close to secret as possible, and its members – as well as the Normal populace at large – safe. A run-in with a nasty creature called a ’serker had seen me injured and in need of a chauffeur for a lot of months, and even after I’d swallowed my pride and let a Weyrd healer fix me up, we’d never got out of the habit of Ziggi driving me around. Besides, our boss, Zvezdomir – ‘Bela’ – Tepes (I’m positive his eyebrows were directly descended from Bela Lugosi) – wanted me to have back-up wherever I went. The memory of the pain inflicted by the ’serker’s claws remained fresh enough to keep me from complaining about having a nanny.

‘Will there be any sitting in cars? I warn you, my personal plumbing no longer reacts well to that sort of stress test.’

‘There are many cafés where we’re going.’

‘Ooh, posh.’ I looked at David, but the bastard just grinned and nodded. He’d been my last hope. David had adjusted astonishingly well to finding out about the Weyrd world that existed – mostly quietly – alongside the ordinary Normal world. Not that he’d had much choice: making a life with me meant getting used to some strange things, like folk who were the stuff of nightmares beneath their carefully cast glamours, the true sight of whom would send any respectable Normal running for torches and pitchforks. Also, like the fact that I was hybrid, a strangeling, with a Normal mother, a Weyrd father and a complicated history, not to mention ridiculous strength – but thankfully, neither tail nor horns nor any other sign of my heritage. And David had taken it all in his stride.

‘Off you go,’ he said. ‘I have manly crib-assembling tasks to do.’

‘You just don’t want to make your child more sandwiches.’ I grumbled a bit more then went to collect my leather jacket – because it was chilly outside – and the handbag I carried nowadays – because wearing the Dagger of Wilusa, the legendary weapon that had saved my backside more than once, on my ankle was no longer a comfy option. All I’d planned on carrying in there was the knife, a simple enough plan. So simple in fact that it hadn’t taken into account what I was now calling Fassbinder’s Law of Handbag Physics, which states that the number of items you want/need to put in a bag will always just exceed its actual capacity.

*

The house had once been a simple workers’ cottage perched on the ridge of Enoggera Terrace that ran through Paddington. At some point it’d been renovated to within an inch of its life: the traditional white picket fence had been replaced by something looking remarkably like a rendered rampart in a fetching sandy hue, hiding everything except a covered carport that sheltered a silvery-grey BMW 3 Series sedan. I was surprised the vehicle wasn’t stashed away in a highly secure garage, but maybe that upgrade was on the way: the Garage Mahal. The monotony of the wall was relieved only by a cedarwood door and a tastefully subtle intercom box.

We’d parked across the road in Ziggi’s impossible-to-camouflage purple gypsy cab, which was neither tasteful nor subtle, and my driver sat quietly while I looked through photos of the house’s interior and yard. It was built on a slope, like just about everything in this suburb; the lower section, originally stilts and palings, had at some point been enclosed and turned into four bedrooms and a family bathroom. The kitchen, lounge and dining rooms were upstairs, along with a small powder room. The polished floors were honey-coloured, and the VJ walls had been painted the colour of clotted cream. If those weren’t the original leadlight windows, someone had made wonderful reproductions. Above each doorframe was a carved panel with a kangaroo and an emu giving each other the Federation eye.

The furniture was mostly in similar buttery tones, with the occasional item of contrasting burnt orange. The LED TV was supermodel thin and a sound system had been unobtrusively recessed into the walls so you barely noticed it. The kitchen had a lot of white marble, stainless steel and pale wood, with appliances that looked brand-new. The bedrooms were beautifully decorated, not a carefully plumped cushion or artfully draped throw out of place. A wooden deck off the kitchen had been accessorised with a cocoa-hued wicker and glass table and chairs for eight, but there was no sign of a barbeque – downright unAustralian, if you ask me – and looked out over the lap pool that took up the length of the back yard. A small tool shed sat in one corner, and drought-resistant plants ran around the fence line.

‘Nice house,’ I said, not at all envious.

Okay, maybe a little.

‘Keep going.’

I flicked over to the second set of photos and whistled. The contrast was marked: what looked like mud was smeared throughout the place, on floors and walls; the claw-foot tub in the bathroom was filled with what appeared to be chocolate mousse. I examined the envelope the pictures had come in; the top left hand corner bore a logo and the name Soteria Insurance.

‘And we’re here because?’

‘Because the owner, Susan Beckett, has recently made multiple claims on the Unnatural Happenstance part of her policy.’

‘Oooooh.’ Very few insurance companies had such clauses, and those who did generally had a particular kind of clientele and only consented to said clauses after a specific request and an impressive hike in premiums. After all, most people had no idea what ‘Unnatural Happenstance’ was and wouldn’t think such cover necessary if they did, but there were clearly a few Normals, not to mention all of the Weyrd population, who knew better. The provision was specifically to cover losses and destruction occasioned by, amongst other things, poltergeists, demonic exertions, hauntings and other revenants – so was unlikely to appear in the paperwork next to anything as mundane as theft of your garden furniture or fusion of your washing machine.

‘And when you say “multiple”?’

‘Three times – the third was last week.’

‘Who called us in?’

‘The head honcho at Soteria is a friend of Bela’s. He called Bela, Bela called me.’

‘Why didn’t Bela contact me?’ I was less offended than curious.

‘He’s trying not to ring too late. He knows you’re sleeping for two now. Also, you yelled at him on the last occasion. For quite a long time.’

That did sound like me. I was out like a light by eight-thirty most evenings, and spent half of my waking hours forgetting why I’d gone into a particular room. Pregnancy brain was doing me no favours. ‘Okay, I’m grateful for that.’

‘Plus he knows David doesn’t like him.’

‘It’s not so much that he doesn’t like him . . . well, yeah, he really doesn’t like him.’

‘Anyway, we are to surveil as subtly as we know how—’

‘Not a lot of space to manoeuvre there.’

‘—and not make any trouble.’ He sighed. ‘We just need to keep an eye out.’

‘A bit difficult to do from here.’ I shifted uncomfortably on the back seat. ‘Do we ever get to interview her?’

‘When we’ve surveilled enough.’

‘Do you have a ball-park figure on how long that might be?’ I peered at the house. ‘It’s just that, while I appreciate Bela putting me on low-stress tasks, I’m fairly bored.’

‘Remain calm, sit quietly and see what we can see,’ he said wisely. In the rear-view mirror I saw him tapping the side of his nose. With a grumble, I settled down to wait.

*

‘There’s a café not twenty metres away,’ Ziggi objected. ‘Can’t you go there?’

‘I love you, Ziggi, and I would do almost anything for you, except right now. I’m just going to ask the nice lady if she’ll let me use her loo. Consider this multitasking.’

Opening the door, I manoeuvred my thirty-two weeks’ worth of bulk out of the taxi with neither elegance nor dignity; it felt like an age since I’d been acquainted with either of those graces. I’d resisted giving up my favourite jeans for as long as I could, but separation was imminent. The belly-band that had kept me halfway decent during the last couple of months was either going to saw me in half, make me pee my pants or snap and ping off into the distance as if launched from a trebuchet. I wasn’t sure which would be worse.

‘But Bela said we should watch. Just watch. Surveillance, remember?’

I didn’t reply, merely quickened my pace, gasping as circulation returned to my swollen ankles and my two-sizes-bigger-than-normal feet. The shirt I was wearing had a three-seater sofa’s worth of fabric in it and ballooned behind me as I tried – and failed – not to walk like a duck. I looked as if I was setting sail. Like an idiot I’d left my jacket in the car with the enormous handbag and the winter air bit sharply; I moved faster.

Susan Beckett, Ziggi had told me while we surveilled, was a twenty-eight-year-old ex-pat lawyer from New South Wales, and had qualified three years ago to practice in Queensland. She worked for Walsh-Penhalligon, a medium-sized firm with nondescript offices on the edge of the CBD; no high-rise, high-cost Central Business District real estate for them. They dealt mostly with commercial litigation and insolvency in the building industry – Beckett was a bankruptcy specialist, indulging in asset-stripping by legal means, which couldn’t have made her popular, so definitely an angle to investigate. The firm’s name sounded familiar, but I couldn’t quite recall why.

I reached the fortress wall and hit the buzzer, hoping with all my heart that Susan Beckett was actually at home – and that she was the type to respond promptly. My luck was in.

‘Hello?’ A cool voice trickled from the speaker and I suddenly realised there was a tiny camera lens embedded in the intercom panel.

I waved. ‘I’m so sorry to bother you – I was out for a walk and I, err, seem to have . . .’ I pointed at my belly.

‘You’re not going into labour are you?’ The tone warmed with alarm.

‘No, but I do need to . . . go. I’m so sorry to impose, but no one’s home next door and . . .’

After a tiny pause, the gate clicked and I pushed through, thankful that Susan’s relief that I wasn’t going to give birth on her doorstep had combined with general human decency to allow me admittance. I stepped into a tiny, highly manicured front yard with a pocket-handkerchief lawn, all lush green stripes, surrounded by beds of architectural succulents, and moved briskly towards the open front door.

‘I’m so sorry,’ I said again to the chic blonde woman, clocking the cream woollen pants, blue linen-knit T-shirt accessorised with an Ola Gorie barn owl pendant on a long silver chain, and embroidered ballet flats from, if my eyes didn’t deceive me, either Etro or Tabitha Simmons. No Ugg boots or trackie pants here.

She waved to a door at the end of a long hallway. ‘Ensuite straight through there.’

Throwing any attempt at elegance out of the window, I waddled as fast as I could into a loo that was Home Beautiful perfect, with a sunflower-painted feature wall, a Carrara marble hand basin sitting perfectly in the centre of a golden pecan bench top, and bright yellow Sheridan hand towels hanging on polished brass hooks. Taps and spouts glowed in beams of light from the frosted-glass skylight and the stained-glass window that overlooked the back garden and across to Paddington and beyond, towards Bardon and Ashgrove.

Enthroned and considerably more comfortable, I could think more clearly. I must have appeared (a) convincing and (b) harmless for Susan Beckett to have let me in so easily. Or maybe she figured she could take care of herself. Or maybe she really didn’t want to risk a puddle by her impeccably maintained front gate.

I was feeling a good deal more focused by the time I finished. I used the Creamy Honey Handwash from L’Occitane (which put my no-name whatever-was-on-special-offer soap to shame), and liberally spritzed Rose 4 Reines house perfume to make sure no trace of me remained. When I exited, it was to find my hostess hovering politely, uncertainly, in the hallway. I smiled as I covertly examined her more closely: wide blue eyes, pert nose, thin lips, sharp chin.

‘Thank you very much. I’m so grateful.’

‘No problem,’ she said, with a distant smile, and swiftly returned to the front entrance. It appeared my visit was to be short – no girly chitchat, no ‘when’s the baby due; do you know what sex?’ cooing – so I peered around, trying to take in as much as I could before I got ejected. There was a bare patch in the sitting room, a square of floorboards slightly lighter than the rest, a spot where maybe a rug was missing. Other than that, it was hard to pick anything off-key. Except . . . except . . . under all the sweetness of the bathroom freshener, under the floral scents of all the lovely things I’d sprayed and washed with, there was a sour odour. I realised I’d smelled it on arrival, but I really had been too distracted to process it then. Now my pregnant-lady sense of smell went into overdrive and my stomach gave a little heave of protest.

It was bitter and brown, rotten, like ripe, nasty, wet shit, and it wasn’t being helped by the warm air being pushed out by the ducted air conditioning.

But the perfectly groomed woman waiting in her stylish clothes, with her expertly straightened hair with the tiny upward flick at the ends, carefully applied make-up and subtle bouquet of Givenchy’s Amarige, wasn’t the source. I was willing to bet she’d done her best – or more likely, paid someone else to do their best – to get rid of the stink and whatever had caused it. Perhaps she couldn’t smell it any more – perhaps she’d become accustomed to that after-note – or perhaps it only affected me, but those efforts at cleansing hadn’t been entirely successful. It would fade only with time and frequent airing of the house as well as the regular squirting of expensive perfumes.

But I wasn’t in a position to ask about it, not yet.

I followed as quickly as I could and let her hustle me out as I gave one last heartfelt thank-you. She was clearly glad to see the back of me, and that was okay. I’d been inside; I’d avoided a very embarrassing personal mishap and I’d learned something important.

Whatever kept hitting Susan Beckett’s house liked to make its mark, and it would return, whether she wanted it to or not.

Chapter Two

‘I saved your life.’

‘Jeez, Fassbinder, I’m not disputing that.’ Aspasia’s long black locks shivered and kinked as if about to become snakelets, which they’d done on previous occasions, but she wasn’t actually angry so the Medusa act was held in check. ‘Seriously, though, how much cake can one pregnant woman eat?’

‘How long is a piece of string, Aspasia?’ I smiled.

With an eye-roll, she put two pieces of my latest craving into a container: hummingbird cake with vanilla frosting and coconut encasing concentric circles of marshmallow, lemon mascarpone and Lindt chocolate. Even Ziggi thought it was too sugary, which was saying something.

‘Thank you,’ I said sweetly.

‘What, no coffee?’ she asked, which earned her a full-on glare. It was a sore point. I hadn’t had a coffee in months: I’d been banned. The first couple of weeks of cold turkey had not been pretty, and a few times I’d been so unpleasant that I’d put myself in the timeout corner.

‘That was uncalled for.’

‘I’m sorry.’

‘No, you’re not.’

‘True.’ She shrugged.

‘And for Ziggi—’

‘I know, I know. Mudcake and a latte.’ She began the process of grinding beans and frothing milk. ‘But really, don’t you think about diabetes? All that sugar?’

‘Well, I do now,’ I whined. ‘Are you trying to ruin this for me? I haven’t seen my feet in months – let me take consolation where I may!’

‘You’re right, you’re right.’

I’d convinced Ziggi that we deserved a treat after three hours of sitting in front of Susan Beckett’s house, so now he was off in search of the ever-elusive West End parking spot while I settled precariously, thanks to my changed centre of gravity, on one of the high stools at the bar. Aspasia watched from the corner of her eye, a little with concern, a little with glee. We were never going to be besties, but we’d been getting on a whole lot better in recent months, which might have had something to do with me saving her and her sisters from a brush with an extremely bolshy angel. While the Misses Norn still bore the scars of that encounter – pinkly healed-over quadrate crosses on Aspasia’s left shoulder, at the base of Theodosia’s throat and high on Thaïs’ right cheek – it had still taken several weeks of intensive arguing as to whether or not the angel’s timely death had been merely a happy accident or the result of tremendous skill on my part before suitable reward had appeared. It might have been gratitude, or pity – because by then I was obviously pregnant – or maybe I just wore them down. I didn’t care: it was free cake.

Improved relations might also have had something to do with the fact that while I was eating Little Venice out of cake and home, my presence was proving a deterrent for less savoury patrons. And after word got out that an actual angel had died upstairs in Thaïs’ rooms, there’d been a stream of sightseers wanting to gawk at the scorch mark on the floor and the Sisters’ scarred skin and to ask stupid questions. Even amongst the Weyrd there are death tourists. Who’d have thought I’d be the one to raise the tone of a place?

I ran my fingers over the grooves of the countertop, feeling the impression of ribs in the fossilised stone, and watched the reflections in the mirror behind the bar, a lovely thing that looked like lace made of snowflakes, indistinguishable from the one that had been shattered in an angelic fit of pique. The clientele of Little Venice was mostly Weyrd, with the occasional lost Normal who wandered in off West End’s Boundary Road and found four big rooms filled with brightly coloured lanterns and incense. An enclosed courtyard out the back was paved with desanctified cathedral stones and covered by a tightly twined roof of leaves and vines that was sufficient to keep off the sun and rain, but didn’t hide the baby snakes that lurked there. The emo-Weyrd waitresses had Lilliputian horns on their foreheads, just along the hairline, but there was enough body-modding in the Normal world that they didn’t cause much comment; they didn’t need glamours to cover them up.

The two floors above the bar formed the Sisters’ private residence; Theo and Aspasia shared the second level and Thaïs had the entire third storey all to herself. Once upon a time, if anyone wanted to see Thaïs to have their fortune told, they had to go to her – never, ever the other way round – but her contact with the outside world had dwindled considerably since the incident with the angel. In addition to being purveyors of food, drink and fortunes, the Misses Norn collected information. News, rumour, and knowledge all flowed through Little Venice, with the Sisters choosing what they shared, what they kept to themselves and what they discarded. They liked to talk in riddles, but since the whole life-saving episode, they’d been more forthcoming with the useful snippets.

‘So what’s new?’ I asked.

‘What have you heard?’

‘Nothing. I hear nothing, Aspasia. I stay at home and I eat. If I’m lucky I sit in cars and I eat, just for variety. Also, I pee a lot. My world has grown small as I’ve grown large with child.’ I leaned forward and pleaded, ‘Please, tell me something interesting!’

Aspasia snorted as she snapped the mudcake into a container and put it next to the others, then stuffed them all into a plastic bag. ‘Sadly for you, not much is going on at the moment, Fassbinder. A couple of kitsune

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...