- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

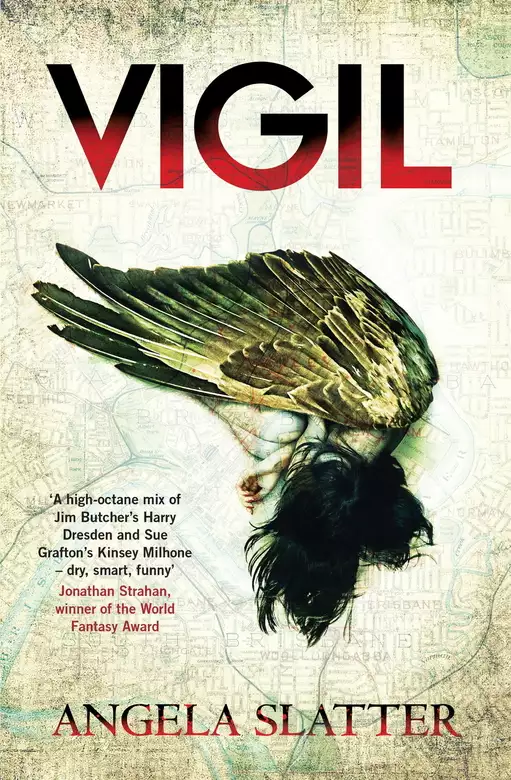

Synopsis

A rich and exciting new urban fantasy, perfect for fans of Harry Dresden and Peter Grant. Verity Fassbinder has her feet in two worlds. The daughter of one human and one Weyrd parent, she has very little power herself, but does claim unusual strength and the ability to walk between one world and the other as a couple of her talents. A rarity, she is charged with keeping the peace, and ensuring the Weyrd remain hidden. But now Sirens are dying, illegal wine made from the tears of human children is for sale - and in the hands of those who hold to old, dangerous ways - and someone has released an unknown and terrifyingly destructive force on the streets of Brisbane. Verity must investigate, or risk ancient forces carving the world apart. Vigil is the first book in award-winning author Angela Slatter's Verity Fassbinder series. 'Slatter's work is excellent, and eminently readable . . . It's easy to see how she's managed to make such an impact on the genre' - British Fantasy Society

Release date: July 7, 2016

Publisher: Jo Fletcher Books

Print pages: 312

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Vigil

Angela Slatter

It had become increasingly apparent that wrapping things was not my forte. Even a simple rectangular gift was obviously too

much of a challenge. Corners broke through the too-thin tissue I’d bought because I’d thought, Hey, an eight-year old would love that! She probably would have, too, if it hadn’t developed holes within moments of me trying to swaddle a big book of fairy tales

in it. The stiff lace ribbon I’d finally managed to tie around the middle looked self-conscious and a bit embarrassed.

Oh, well. Lizzie would turn the gold and silver paper into confetti in a matter of seconds anyway. I could hear the sounds

of the birthday party-cum-sleepover already ramping up next door, and looking through my kitchen window into Mel’s garden

I could see a circle of small girls in pastel party dresses made of shiny fabrics, glitter and sequins. They all wore fairy

wings that caught the last of the sun’s rays as they danced and ran, lithe and careless as sprites. It made me smile. Mums

and dads were scattered across the grass, some carrying platters of cocktail sausages, fairy bread, mini pies and other essential

party foods while others seized the opportunity to laze around being waited on. It would be nice, I thought, to socialise,

do something ordinary for a change.

I took a last look in the mirror to make sure I was presentable – or at least as presentable as I was likely to get. I picked up the offering, and that’s when the hammering started at the front

door. It wasn’t the good kind of knocking and my spirits sank. Things didn’t improve when I saw who was waiting on the patio.

Zvezdomir ‘Bela’ Tepes, model-handsome in pressed black jeans and a black shirt, managed his usual trick of appearing ephemeral

as a shadow, yet as all-encompassing as darkness. He gave a wave so casual it could have been mistaken for a dismissal. Just

seeing him made my leg ache.

‘Verity. I’ve got a job for you.’

‘But I’m going to a birthday party,’ I blurted, clutching the present like a shield. ‘There’ll be cake, and lollies.’

He blinked, caught off guard by my unlikely defence. ‘I need you to come right now.’

‘Party pies, Bela. Fairy cakes. Mini sausage rolls. Small food,’ I said, then added lamely, ‘It tastes better.’

‘Kids are going missing,’ he said, gritting his teeth, and it was all over bar the shouting. ‘And someone wants to talk to

you.’

He pointed towards the familiar purple taxi parked at the kerb in the late afternoon light. There weren’t too many cabs like

this in the city, although I guessed demand would be growing as the population did; it wasn’t just people fleeing the southern

states who wanted a new start in Brisbane – also known as Brisneyland or Brisrael if you were feeling playful, or Brisbanal

if you were tired of restaurants closing at 8.30 p.m. The taxi’s general clientele covered Weyrd, wandering Goths and too-plastered-to-notice

Normal, though most times even the drunkest thought twice about getting into this kind of car. It was almost like they were

snapped out of their alcohol-fuelled stupor by the strangeness it exuded.

Through the passenger window I made out a fine profile and meticulously styled auburn hair. When the head turned slowly towards me, I recognised its owner, though I’d not formally met

Eleanor Aviva, one of the Council of Five, before. It was a bit like having the queen drop in. The driver next to her gave

a brisk wave.

My shoulders slumped. ‘How many kids?’

‘Twenty-five we can identify for sure, but that’s out of a couple of hundred a week. Not all those are ours.’

‘Don’t say ours, Bela. They’re nothing to do with me.’ I regretted the comment as soon as I said it; people had looked out for me when I

needed it and I’d determined long ago to try to pay that back. ‘Let me drop this off, make my apologies.’

‘Don’t be long,’ he said. As he retreated to the vehicle I made a rude gesture behind his back, which Eleanor Aviva saw. After

a moment, her very proper mask cracked and she gave me a conspiratorial smile, then faced forward again.

As I dragged my feet towards Mel’s house, I wondered if Lizzie would save me some ice cream cake.

*

I looked out of the window. My reflection stared back, and beyond that I watched the night speed past. I should be singing

‘Happy Birthday’, not here with my ex in the back seat of the world’s most disreputable-looking gypsy cab. Parts of it had

been cannibalised from other cars. Any original white surfaces had been reduced to grey, and the vinyl of the seats was a

little sticky with age. The rubber mats on the floor, though so thin as to be almost transparent, were, I was pretty sure,

all that stopped me from seeing the bitumen of Wynnum Road beneath us. Instead of the traditional pine tree-shaped air freshener

there was a gris-gris hanging from the rear-view mirror. It wasn’t minty-fresh, but then again it didn’t smell bad – it was rather cinnamony, if

anything. It just looked bad: a shrunken head with dried lavender sticking out of its ears. Scratched along the inside of the doors were symbols and sigils I couldn’t read,

in a language so old I suspected no one knew how to pronounce it any more. I never looked too close, not since I’d realised

that some of the etchings were really fingernail marks. I didn’t want to linger on that thought.

‘It’s only been street kids so far,’ said Bela. He didn’t even stumble on that bit – he didn’t even know he’d said the wrong

thing, though no column inches were going to be devoted to those lost children. In the front seat, Ziggi loaded a CD and the

exquisite a cappella opening of ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ poured forth. Eleanor Aviva made an annoyed clicking sound with her tongue.

Philistine.

‘Turn that racket down,’ Aviva ordered in clipped tones, and to my mild surprise, the driver obeyed without argument. The

councillor retreated back into silence. Despite Bela’s earlier comment we’d not been introduced and I wondered why she was

here.

The eye in the back of Ziggi Hassman’s head examined me through fine ginger hair. He’d landed in Brisbane about ten years

ago and got a job with Bela immediately, thanks to a sheaf of references, so we’d known each other for a long time and I could

generally interpret his expressions, facial – and otherwise. But I’d not seen that single orb as inscrutable since I’d ended

up haemorrhaging on his back seat after following him and Bela into an abandoned house a few months ago . . . coincidentally,

that was the same night I’d lost my enthusiasm for the phrase ‘let’s split up and cover more ground’. We’d been looking for

something that shouldn’t have been there – shouldn’t have been in this plane of existence. It was a something with claws and

teeth and a bad attitude; a something that had been making red messes of pets around the city. Luckily, not people. Not then,

at least.

I found it first, and won the fight that ensued, but ultimately wound up in Accident and Emergency. Ziggi had saved my life,

wrapping every bandage from the taxi’s first-aid kit around my leg to stem the bleeding while Bela had busied himself making

phone calls to highly unlisted numbers and reeling in favours while reporting to superiors, which added another couple of

layers of resentment to how I felt about him.

‘I should be eating ice cream cake,’ I announced to no one in particular. ‘I should be watching Lizzie open her presents.

I really should.’

‘Verity, if it’s—’ Bela started.

‘It’s not, Bela’ I said shortly, pressing down on the rage his voice habitually produced in me nowadays. Before I could give

rein to my full displeasure, I was distracted by the vibration of the mobile in my jacket pocket and reached for it.

‘Ms Fassbinder, kindly give us the courtesy of your undivided attention,’ Eleanor Aviva said sharply and my hand fell away

as I instinctively sat up straighter, the response to that schoolmarm tone deeply ingrained.

Bela tried again, and his pitch was softer. ‘V, if it is, then maybe it’s like your dad.’ He waited for me to speak, to deny the past, to defend myself. I rewarded him with silence,

so he went on. ‘If it’s a Kinderfresser—’

‘Well, at least we know it’s not my daddy this time,’ I sniped.

‘—then we need to get to him quickly because he – or she – won’t stop by themselves. I can’t keep this out of the papers for

too long. Any undue attention on our community will put everyone in danger.’

There was a time, not so long ago, when I’d been bleeding and screaming in the back seat of this very taxi and swearing I

wouldn’t ever work for Bela Tepes again, yet here I was, listening meekly to what was expected of me. The weekly retainer

was deposited into my account on the assumption that I’d do what was asked. I might not have followed through on my plans to quit – quite frankly, what else was I going to do with an Arts degree in Ancient

History and slightly dead languages? – but that didn’t make me feel any more biddable.

‘Do you really think I don’t know that?’ My glare was enough to make him look away. Then I felt bad; my temper had become

short and my nature less than pleasant in recent months and it was Bela who was bearing the brunt of it. Then again, once

upon a time I didn’t ache inside with every step; I didn’t wake up sweating, thinking something was at my window, and I didn’t

dream of claws reaching through the gaps in the stairs and tearing so much flesh from my leg that I looked like I’d been ring-barked.

‘Perhaps Ms Fassbinder isn’t really the person for this task, Zvezdomir?’ said Aviva evenly. She pronounced his given name

with an assurance and an accent I’d never manage in a hundred years, which was one of the reasons I so seldom used it. That

and the Bela Lugosi eyebrows.

‘Ms Fassbinder is the only person for this job, Eleanor.’ Bela matched her timbre, but there was an underlying edge.

Part of me wanted to tell them both where to go, but the sad fact was that I needed money. Though I owned the house, things

like food and phone bills didn’t get paid with a sunny smile. Things had been quiet in Weyrd-town recently, and the Normal

world hadn’t been much busier, so the independent consulting assignments I did occasionally had been few and far between too.

Bela was a generous paymaster – possibly because his missions were generally the reason I ended up in harm’s way – but we’d

broken up two years ago and the job meant closure was an issue. Spending all this time together – and not happy fun times

– meant I kept wondering when the ‘ex’ part of ex-boyfriend would kick in.

‘Ms Fassbinder, I cannot stress strongly enough how important it is that this matter be dealt with swiftly and shrewdly,’

Aviva said. ‘And quietly. Any member of our community who risks exposing the rest of us to danger has no rights in the eyes

of the Council. There is to be no prevarication, and no mercy for this individual.’ She tapped long fingernails on the dashboard

in front of her. ‘Of course, you know that better than most.’

Behind my head, Freddie Mercury’s voice soared, but quietly, as if afraid of Eleanor Aviva’s disapproval. I controlled my

breathing, counted to ten and remained calm. ‘Has anyone thought about asking the Boatman if he knows anything? I mean, all

the dead end up with him eventually.’

‘I don’t think that’s necessary, do you?’ said Aviva. ‘He hardly chats with his passengers. He obeys his own rules, answers

to none, keeps his own counsel. He does not come when called.’

She was probably right, but it felt like she was baiting me and I had no idea why. Her attitude wasn’t improving my mood.

‘I don’t mean to be rude, Councillor, but why are you here? The Five have always kept their distance from me.’

‘Consider this a performance appraisal,’ she answered, not even bothering to look over her shoulder at me. Was she trying

to get a reaction? Did she not realise I’d spent my life ignoring stuff like that? I smiled at Ziggi’s stare in the rear-view

mirror. It had gone from inscrutable to concerned.

Bela, apparently not confident of my self-control, raised his voice to drown out any reply I might have made. ‘Eleanor and

I are on our way to a Council session and she wanted to take the opportunity to meet you. I assured her you’d treat this matter

seriously.’ He cleared his throat. ‘Where are you going to start?’

‘I’ve got some ideas.’ I could feel his gaze, even though I was peering out of the window again. I thought he might be staring at my neck, at the pale curve where the vein pulsed blue close

to the surface. I wondered if he was remembering what the sweat on my skin tasted like. I didn’t turn around but said softly,

‘It’s okay, Bela, leave it to me.’

‘Ziggi, keep an eye on her,’ he said abruptly. ‘And V, when you’re done with this, there’s something else I want you to look

into.’

And he was gone, just like that, leaving the seat beside me empty, smelling vaguely of his expensive aftershave, a chill coming

off the faux-leather. Eleanor Aviva had evaporated too. That disappearing act was draining in the extreme and only a very

few Weyrd could do it. Things were quiet, except for the final coda of Freddie’s delicate piano work.

‘I hate it when Bela does that. Freaks me out,’ said Ziggi, the only other person I knew who got away with using that nickname.

Bela made even other Weyrd uncomfortable. I felt kind of proud, in spite of everything.

‘He used to just appear in the kitchen. I dropped a lot of dishes,’ I admitted, then bit down on my lip – I hadn’t meant that

to slip out, hadn’t meant to dwell on the past domestic situation. It wasn’t as if Ziggi hadn’t witnessed all the ups and

downs of my relationship with Bela – he once claimed he didn’t watch TV for three years because we provided all the drama

he needed – but I felt compelled to say, ‘It takes a lot of effort, so that’s how I gauged how much he wanted to get away.’

‘You were a little challenging,’ he pointed out. ‘You need to cut him some slack, you know.’

I didn’t answer; we both knew Ziggi was right. He hesitated, then said, ‘How’s your leg? I mean, really?’

‘How the hell do you think it is?’ Even as I snapped at him, I knew I should have been a bit more gracious. ‘I’m sorry I’m being an arse. It still hurts, and that makes me cranky.’

‘To be honest, you were pretty cranky before it happened.’

We laughed and the tension dissipated.

‘You were trying to annoy Aviva, weren’t you?’ I asked. ‘With the music.’

‘What do you think? I don’t like uppity folk who think they’re better than everyone else.’ He sniffed. Ziggi Hassman: melodic

anarchist.

‘Turned it off pretty quickly though.’ I grinned.

‘Hey, I’m not stupid.’ Then, unable to resist it, he circled back to his topic of choice. ‘Should’ve gone to a healer with

that leg of yours.’

‘Well, if you remember, there wasn’t much time to fiddle about that night and the hospital was closest,’ I pointed out. The

upshot of my injury was that Ziggi had become my chauffeur, so we’d been spending a lot of time together while doing Bela’s

assorted jobs. We investigated things that needed looking into, acted as go-betweens and problem-solvers for him – and by

extension, the Council – and generally kept an eye on the Weyrd population, trying to make sure it stayed as unknown as possible.

This was sometimes a challenge when the community included those who were still looking for a taste of the old days: feline-shaped

things who stole breath, succubi and incubi out for a good time, and creatures who swapped their own offspring for babies

left unguarded in their cribs.

He gave a grunt that might have been a concession. ‘So, where to? You said you’d got some ideas?’

‘I might have exaggerated. I have one idea. Let’s start with Little Venice.’

‘Probably should have told me that three seconds ago when I could have taken the turn-off,’ he said mildly. ‘Now we’re going the long way round.’

He cut off a dully-gleaming SUV to change lanes. The sun had fled, and as we drove onto the Story Bridge, the lights of the

city down and to the left, and those of New Farm down and to the right, swam in the blackness. High-rise office towers stood

out like beacons, standing cheek-by-jowl with the new apartment blocks: all that modern steel and glass juxtaposed with the

verdigris dome and sandstone of Customs House and the past it represented. During the day, the river would show its true colour

– a thorough brown – but in that moment it was an undulating ebony ribbon reflecting the diamonds of night-time illuminations.

‘It’s okay. We’ve got nothing but time,’ I lied and hunched into the upholstery, thinking about melting ice cream cake and

kids who wouldn’t ever know what that tasted like.

West End was filled with Weyrd.

Most folk thought the Saturday market’s demographic was a mix of students, drunks, artists, writers, the few upwardly mobile

waiting for rehabilitated property values, religious nutters, common-or-garden do-gooders and dyed-in-the-wool junkies, all

mingling for cheap fruit and veggies – or to score weed in the public toilet block in the nearby park. Often these groups

overlapped.

But there was also a metric butt-load of Weyrd, who sometimes featured in one or more of the aforementioned groups as well.

They were mostly successful in their attempts to blend in, especially in suburbs that already had a pretty bizarre human population

– places where it was difficult to distinguish the wondrous-strange from the head-cases. The old guy who yelled at the trees

on the corner of Boundary Street and Montague Road? Weyrd. The kid who kept peeing on the front steps of the Gunshop Café?

Weyrd. The woman who asked people in the street if they could spare some dirty laundry? Well, actually, she was Normal. The

smart ones used glamours to hide what they were, to tame disobedient shapes and disguise peculiar abilities, but some just

let it all hang out, not caring if they were mistaken for psychos or horror movie extras.

They weren’t a disorganised rabble; any minority group keen on survival soon develops its own leadership. The Weyrd had the

Council of Five, chosen from the old families who’d been in Brisbane since its founding. Convicts, overseers and frock-coated

men on the make weren’t the only ones doing the invading; lots of folk wanted a new start. In the Old Country – wherever that

happened to be – the ancient beliefs and traditions still held sway. Normals were twitchy creatures, but they’d only live

in fear of the dark for a limited time. Eventually they got tired of huddling around fires and being scared. As with anything

that went on for too long, numbness and fatigue set in, followed by anger, which burned out a lot of the good sense that’d

brought on the terror in the first place. They got all brave and started charging around brandishing torches and pitchforks,

striking out not just at whatever had frightened them but at anything that was different. Problem was, it wasn’t really bravery, it was still fear – but it was an enraged fear, and that kind wasn’t discriminating. As a consequence, the Weyrd – the different – from Hungary to Scotland, Romania to Mali, Italy to Japan, the Land Beyond the Forest to several dozen tiny nations that

had changed their names multiple times, people like Bela, Aviva, Ziggi or my father, often had to find new homes, or cease

to exist . . .

So the first Weyrd came over on their creaking, stinking, packed ships, as stowaways, or convicts, caught by accident or intent,

sometimes even as soldiers or governors or wives. Those who survived to put down roots in the new land, who set up shop as

the major cities developed, generally became the Councillors, keeping watchful eyes on the rest of the Weyrd population. They

ensured peace and dealt with the Normals, using people like Bela – essentially a cross between prime minister and spymaster

– to keep the worst ‘disturbances’ under control. And someone like Bela would employ someone like me, because those of us

of mixed parentage can walk between the two worlds. As long as we behave ourselves and don’t cause a fuss.

It had gone relatively smoothly until I got injured. Quite apart from my freshly acquired physical limitations, the ancient

car I’d inherited from my grandparents had been found burning outside my house a few hours after I’d been admitted to hospital.

The insurance payout was just about enough to buy me a second-hand pair of running shoes. The net result of that particular

evening had been one dead ’serker, a long-term limp for me, and a new chauffeur.

‘You think they’ll know anything?’ Ziggi had been trying to find a parking space for about ten minutes, although in the grand

scheme of things that wasn’t a long time in West End. I figured he had maybe ten minutes of patience left, but I had about

two.

‘There’s a good chance. Whether they’ll be willing to share? That’s the real question.’ As we passed Avid Reader for the third

time I noticed the snail-trail of people waiting to get their books signed by the author sitting in the window had dwindled.

‘Do you know what this other something is that Bela wants to talk about?’

He sort of shrugged and made a noise that didn’t answer me one way or the other.

‘Ziggi.’

‘Not sure. He met with Anders Baker today, but that might be unrelated.’

I frowned, but didn’t say anything. Anders Baker was a self-made gazillionaire thanks to a variety of import-export concerns,

land development and general dodgy deals, including, so rumour had it, brothels, porn movies and some rather heavy-handed

loan businesses. He was Normal, so I wasn’t quite sure why he and Bela would be having dealings, unless it was to do with

his once-upon-a-time wife; she’d been Weyrd, so maybe that was the connection.

We were about to begin another loop around the block when I decided enough was enough. ‘How about you let me out here and I’ll text you when I’m done.’

He pulled up, blocking the flow of traffic, and a chorus of car horns began. ‘If it’s Aspasia,’ he said, ‘be polite – you

catch more flies with honey than vinegar.’

‘So my grandma used to say.’

A great number of Weyrd didn’t cause problems but lived as quietly as they could. Although many were moon-born and preferred

the night, most of them didn’t roam the dark hours. They were generally good citizens, paid their taxes, held down all sorts

of jobs and kept their secret selves hidden, or at least camouflaged. There were a few places, however, where they could just

be themselves, and Little Venice was one of them.

The name was an in-joke, because none of the floods that periodically overran Brisbane had ever touched the place, not even

when everything else in West End was under water. It looked ordinary enough: a three-storey building, commercial premises

below, private residence above. The café-bar was cute: dingy little entryway lapping the street, long thin corridor leading

into four big rooms filled with shadows and incense. Out back was an enclosed courtyard paved with desanctified cathedral

stones, not used much during the day except by stray Normals; its tightly twined roof of leaves and vines was enough to keep

off the sun and rain, but not quite enough to hide the snakes that lurked there. Through the wide archway I could see the

space was packed, everyone swaying along contentedly to a man with a sitar accompanied by another playing a theremin. Two

emo-Weyrd waitresses, managing to look both bored and alert, sloped between tables delivering drinks and finger food. Both

had Lilliputian horns on their foreheads, just along the hairline; in the Normal world they’d probably be written off as body

mods. They might even have had vestigial tails to match, but Weyrd blood ran wild and it was almost impossible to predict how offspring

would turn out.

When I needed information, this was where I generally started. Gossip washed through Little Venice like a river, the three

Sisters who ran the place judiciously deciding what stayed behind and what got carried away. They were equally picky about

what they shared. But even when I wasn’t looking for anything, I still came here, because they did good coffee and amazing

cakes: fat moist chocolate, rich bitter citrus, and a caramel marshmallow log that could stop your heart.

In addition to the business of hospitality, the Misses Norn – possibly not their real name – took turns reading palms, cards

and tealeaves, each having her preferred method. For twenty bucks you’d get a traditional fortune-telling; fork out a heftier

sum and you could see your future in runes, entrails or crimson spatter – in short, the more you paid, the nastier it would

get. Maybe the latter were more accurate, but it was hard to know because each choice you made changed something else, shifting

Fate like unruly chess pieces. The very willingness to spill blood might be the thing that knocked your destiny out of true.

But one thing remained constant – or constantly inconsistent: no matter which modus operandi, one Sister genuinely laid out your choices, one made your fate with her words and the third simply lied. Problem was, you couldn’t really tell which did which. They weren’t malicious,

just Weyrd. It was their thing.

I’d been hoping for Theodosia because we got on better, but Aspasia was working the counter, so I kept Ziggi’s advice in mind.

Behind her was a mirror that looked like lace made of snowflakes. She gave me a cool smile as I limped in. This Sister was

all dark serpentine curls, obsidian eyes, occasional prickly personality and red, red smile. When her lips opened I could see how sharp

her teeth were.

‘Fassbinder. Come to have your fortune told?’ Her smile widened and she gave a shimmy and gracefully extended her hand, a

belled bracelet making a gentle chime. ‘Cross my palm with silver, girly.’

I shook my head. ‘My answer’s the same as it’s always been – surely you could’ve seen that coming? But I will take a long

black, some information and a slice of that caramel marshmallow log. And a super-sweet latte and a piece of mud cake to go.’

She pursed her lips. ‘You got a new boyfriend?’

‘Hardly.’ I considered the idea of Ziggi-as-boyfriend, gave a little follow-up shudder and sat carefully on one of the tall

stools, letting my sore leg dangle. Elbows resting on the countertop of fossilised stone, I grinned. I have a good grin, nice

and bright, disarming. ‘It’s lovely to see you again, but this isn’t a social call.’

‘Colour me shocked.’ Of course she wasn’t going to make it easy. We might manage to be civil to each other but she’s always

held a torch for Bela and she’s never quite forgiven me for dating him as long as I had. Or at all.

‘Kids are going missing.’

‘So sad,’ Aspasia said lightly, and began caressing the coffee machine – which looked like the console of a spaceship – into

doing her bidding. It started bubbling and spitting, a comforting sound that made conversation impossible for a little while.

I traced patterns on the stone bench, thought I could make out the impression of a rib or two. After my drink had been assembled,

Aspasia extracted the cakes

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...