- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

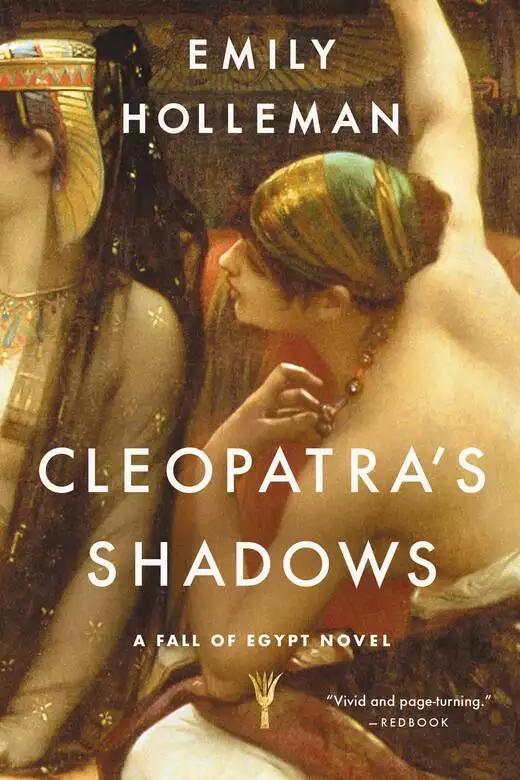

Synopsis

The only way to survive her dynasty is to rule it.

Abandoned by her beloved older sister, Cleopatra, and an indifferent father, Arsinoe, a young Egyptian princess must fight for survival in the bloodthirsty royal court after her half-sister Berenice seizes power.

But despite using her quick wits to win Berenice's favour, Arsinoe struggles to establish herself in an uncertain new world, one that carries her from the conspiratorial dangers of the palace to the streets of war-torn Alexandria.

Meanwhile, her other sister, the usurper Berenice, has her own demons to confront - her cruel, flagging mother, a pair of fickle husbands, and the ever-present threat that her father will return from exile—as she fights to hold the throne as the first queen of Egypt in a thousand years.

Perfect for historical fiction fans who loved discovering The Other Boleyn Girl, Cleopatra's Shadows reimagines Cleopatra's rise to power through the eyes of her forgotten younger sister, Arsinoe.

Release date: July 5, 2016

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Cleopatra's Shadows

Emily Holleman

Neither did she. But just as Cleopatra couldn’t tear herself away from this vigil, Arsinoe felt compelled to join in the obsession. As though her presence might tug the madness from her sister’s mind, banish the moping changeling who slunk about in Cleopatra’s form. Scant months ago, her sister had been the toast of the Alexandrian court, impressing bureaucrats with her knowledge of the Nile’s whims and charming ambassadors with witticisms in their native tongues. But now, when Egypt needed her most of all, Cleopatra had retreated from public view. Instead, she huddled here beside their father’s bed, her dark curls wreathed by her white diadem. And, dutifully, Arsinoe knelt at her side.

Before this shadow of a king, Arsinoe felt ashamed of her old fears. Four years ago, she’d quaked as her father’s armies surrounded Alexandria. She’d been eleven then, and everything had frightened her in those girlhood days: first when her sister Berenice’s coup sent the Piper mewling to Rome, and then when Rome’s legions brought him back. On his return, Arsinoe fled the palace and disappeared among the street children, hiding from her father’s wrath. Dragged back to court, she watched as the Piper ordered his eldest daughter’s execution. As he laughed at Berenice’s head flopping onto the stone and spat into her empty eye. Fitting, now, that he would join that daughter in death. His ka would pass from his body and cross into the next world, where the gods would judge him on these deeds. Perhaps they would look upon him more kindly than did Arsinoe.

The husk before her fluttered and wheezed: the New Dionysus cut down by plebian mortality. Perhaps long ago, when Alexander the Conqueror’s blood ran thick through her ancestors’ veins, it had been enough to be a Ptolemy, but no more.

With a groan, the man craned his neck. His eyes squinted with determination. His fingers seized and twitched, reached out, past her, to take hold of Cleopatra’s hands.

“My dear,” he murmured.

Arsinoe’s fists tightened at her sides. But, no, this closeness between her father and her sister could not hurt her anymore. She would look on, a stranger indifferent to their bond.

As though he’d heard her thoughts, the king glanced at her, his eyes bright and strangely merry in his sunken face. No matter how the rest of his body strained and atrophied, those eyes belonged to a much younger man. She lifted the corners of her mouth: a small kindness. Her father was dying; she could afford to be generous. To her surprise, he smiled back—grimaced, more; lips straining toward his hollow cheeks—but she recognized the intent. His fingers tugged at the air to draw her in. She couldn’t believe it—it wasn’t possible, not after the years of slights. But there it was again, that clawing gesture, reeling her in.

Arsinoe leaned forward and reached her hand across the bed. Perhaps she’d been too stubborn all this time, refusing evidence of her father’s love. As Cleopatra so often reminded her: the Piper couldn’t have known what would befall him and Cleopatra in Rome, just as he never could have guessed what awaited Arsinoe in Alexandria. And so he’d done what kings and gamblers do: he’d split his odds, leaving one daughter and taking the other. Chance, not callousness, had left her, Arsinoe, behind.

Her father coughed, an angry racking of his ribs. She moved to take his hand, but Cleopatra’s was already there.

“Leave us, my sweet,” her sister whispered. Her tone was gentle, ever apologetic for the Piper’s partiality. The pity smarted on Arsinoe’s ears.

Her father twitched his fingers again. The movement didn’t beckon—she saw that now—it dismissed. A smile, a look, a turn of a wrist—none of it could wipe away the past. He was a dying man, of no use to anyone. She wouldn’t—didn’t—ache for gestures of love and mercy. As she stalked from his sickroom, she smashed her fist against the ebony doorjamb.

Back in her chambers, Arsinoe stretched on her divan and marveled at her strange quandary. After her days among the urchins, she’d returned half wild to the court, clinging quietly to the name she’d adopted in the alleyways: Osteodora, the bone bearer. Only Cleopatra had had patience for her then. Her sister had coddled and humored her, no matter how hard Arsinoe had pulled away. Now the ledgers had reversed: Cleopatra needed Arsinoe’s protection. Distracted by their father’s illness, her sister was blind to the men jockeying to position their brother as the Piper’s heir.

Shouts echoed up from the courtyard, and Arsinoe went to her window to see the cause of the commotion. Across the garden, a horde of Romans had gathered outside her brother’s chambers. Her stomach still turned at the sight of these men, though she’d grown accustomed to their presence. In the months after her father’s restoration, she’d watched as foreign galleys descended on Alexandria, carrying off the city’s grain and gold. That, she’d realized, was the price their father had agreed upon to buy back his throne: ten thousand talents to the Roman general Aulus Gabinius and an unrelenting supply of wheat to the insatiable Republic. The ships had brought a fleet of rats as well as soldiers, sinewy creatures who’d taken up eager residence in the kitchens. The rats at least were easier to get rid of.

A hefty man in a crimson cloak addressed the interlopers. When Arsinoe squinted, she recognized him as her brother’s rhetoric tutor, Theodotus, his elephant ears betraying him even at this distance. She studied his lips, and slowly, she managed to work out his words.

“Like his father, Ptolemy recognizes your sacrifices. He knows that without your aid, our city would not have arrived at peace. In recognition of your loyalty, he has ordered that you each receive another five plethra of farmland.”

The Romans roared, full-throated and in their mother tongue: “Ptolemeus rex. Ptolemeus qui rex erit.”

Ptolemy the king. Ptolemy who will be king. The legions loved her brother, and with reason. Every day more fields spilled into Roman hands, all in the name of young Ptolemy’s generosity. Theodotus was no fool—he knew rich swaths of land would bind Gabinius’s erstwhile officers to his charge over Cleopatra. The soldiers distrusted her sister for what she was: an Eastern woman with an eye for rule. Hadn’t they already deposed one of those? In Rome, Cleopatra had told her once, slack-jawed with shock, women are chattel, no more and often less. Or as Arsinoe had heard more than one centurion sneer after Berenice’s death, In Rome, women know their place.

The sun’s last glimmers had drained from the bruised sky by the time Arsinoe heard her sister creeping up the stairs. Quickly, she wrapped her woolen mantle about her shoulders and skirted out onto the balcony that joined their two sets of rooms. For hours she’d waited, knitting together an argument to convince her sister that she must rejoin the world of the living: Cleopatra needed to acknowledge their brother as a threat. But when she caught sight of her sister— head bowed, eyes red with tears—all her carefully plotted points evaporated.

“Clea.” Arsinoe grasped her sister’s hands. “What’s wrong?”

“What’s wrong?” Cleopatra jerked her hands away with an almost maniacal laugh. “‘What’s wrong,’ she asks. Our father is dying.”

The words cut as intended. “I know,” Arsinoe said, firming her resolve, “but you must—”

Her sister pushed past her, prying open the door to her own chambers. Dumbly, Arsinoe followed. Cleopatra collapsed on the first divan in sight, sending Ariadne, the tiger-striped cat she kept, spinning off in mewling protest. The creature didn’t run far; she turned back to stare at her weeping mistress, her eyes a pair of unblinking emerald saucers. Tears poured in great rivulets down Cleopatra’s cheeks.

“My sweet.” Arsinoe knelt at her sister’s side. She tried to summon sympathy—but her gentleness had been spent. The image of the courtyard, overrun with Romans, remained fixed in her mind. She could still hear their shouts: Ptolemy who will be king. How much longer, she wondered, would it be before Theodotus dispensed with niceties and set her brother firmly on the throne? “My sweet, tomorrow, promise me you’ll come to the atrium. The guards, the bureaucrats—they, too, are suffering. Your brave face would give them courage.”

Cleopatra snickered again, a cruel echo of her former self, the one who’d always been ready with a smile and a jape. “Why? They see your brave face often enough. Look at you. Untouched and un-burdened. Your eyes and cheeks as bright as ever. As though our father wasn’t dying.”

“Th-that’s not fair.” Arsinoe stammered over the paltry words. What else could she say? She couldn’t lie to Cleopatra, and she didn’t dare speak the truth. Her sister clung to this adoration of their father; it was the last indulgence of their childhood, and Arsinoe wouldn’t spoil it—not unless she had no other choice. “Someone has to keep an eye on the goings-on at court.”

“That’s what Father has advisors for.”

“Yes, but you know what those advisors are doing: they’re propping up our brother. Every day you spend tucked away in our father’s chambers, Theodotus and Pothinus and all the rest are trotting out that boy as their new king.”

“Ptolemy is a child, Arsinoe. Barely out of changing clothes.”

Her sister’s blind spots astonished her. Cleopatra was a quick study, able to divine the backstory of each passing diplomat, every official tallying the crops of the Upper Lands. And yet when it came to their brothers, she lacked all sense of proportion. She’d never paid either much mind, never remembered which tutor was assigned to whom; she’d never had to. The favorite, she had been whisked away too often by their father on some adventure. Arsinoe, on the other hand, had long years of observing behind her. She knew what sort of men backed her brother; she knew how desperately they would clamor for their protégé, no matter how unworthy. Ptolemy might be a boy, but one day he’d grow into a man.

Arsinoe tried once more. “It isn’t just Ptolemy you need to worry about. It’s his councilors—”

“Trust me to handle a boy and a few thumb twiddlers. I am Father’s co-ruler; I am already queen. My name alone appears on the will that Father entrusted to the Sibylline Virgins. You worry too much.”

“One of us must.”

“I worry plenty for the both of us. But I also made a promise to our father. He is dying, Arsinoe, and he is frightened. I won’t”—and here her sister’s voice trembled—“I won’t let him die alone.”

A specter of impotence stretched before Arsinoe: Cleopatra locked up in the royal chambers as weeks became months. Who knew how long the king might teeter between life and death? A cruel thought flickered in her mind. If Cleopatra didn’t wish to leave the Piper’s side until he faded into the next world, perhaps it would be better to quicken his passing.

The idea—unnatural, despicable—riled her. Desperate to push it from her mind, she cast about for a distraction, scouring the walls and corners of the room, all ringed with the dancing nymphs and piping satyrs their father so dearly loved. Here and there, Cleopatra’s tastes crept in: a woven map of Alexander’s conquered kingdoms; a terracotta vase depicting Medea in her dragon-drawn chariot; a delicately carved statuette of the goddess Isis cradling her infant son.

“Arsinoe.” Her sister’s voice cut soft and sad. “Dear one, I know it hasn’t been easy for you.”

Cleopatra slid her calves over the edge of the divan and lowered herself to join Arsinoe on the floor. A whiff of Cleopatra’s familiar scent—rose tangled with lilacs. As they sat back to back, spines fused as one, Arsinoe felt she might conquer the world. Turn the Romans out and put an end to all her house’s shameful indiscretions. The past could be cleansed. Her father’s decline was proof of that.

The world sharpened: omens stiffening to fact. The king would die; the only question was when. Visions had haunted her, ever since she was a little girl, and now, each night, it was her father’s corpse she came upon in her sleep, stiff and empty eyed. Perhaps, at last, she should embrace her dreams as portents—commands, even. If the gods were determined to make her the harbinger of someone’s doom, why not her father’s? He had abandoned her; he would ruin Cleopatra. With each fleeting hour of the Piper’s decline another advisor pinned his hopes on her brother. The king’s sickness was a plague on every one of them.

“Theodotus grows bold. Today he handed out new leases of land in the Marshes, reminding the Romans that the king’s son recalls their service to the crown. Ptolemy may not frighten you now, but his advisors should. They will fight to secure his throne; they’d rather have a malleable boy in whose name they might rule than a sovereign queen.”

Arsinoe felt Cleopatra’s back tense against her own, but she knew she must press onward. The time had ripened; another moment and it would spoil. And who was to say what their father wanted? He might well embrace death as a blessing, an end to his painful, grating breaths. A darker drive spurred her on as well; she wanted to test her sister’s love. It couldn’t be as pure as it appeared.

“Our father is suffering, and Egypt too,” Arsinoe continued. Her innards tightened. “Perhaps the time has come to hasten...” Her voice caught in her throat. What sort of twisted daughter was she? Cleopatra shifted away, nearly toppling Arsinoe to the floor, and stared at her with ugly, jagged eyes. As though she was recognizing for the first time the loathing that lurked in Arsinoe’s heart.

“And what do you suggest?” Cleopatra spat. “What do you mean by that?”

“I meant nothing,” Arsinoe lied. I meant that we might kill him, you and I. Did she have the stomach for murder? For patricide? There’d been that boy in the streets of Alexandria, on the eve of her father’s return. Her first night outside the palace, she’d hidden in the catacombs. The boy had cornered her, and something had snapped inside her. She’d grabbed the only weapon in reach: a bone. She could still hear its crack against his skull, still see his body slumped on the ground. But that had been Osteodora’s doing, not Arsinoe’s.

“No, you meant a great deal by it.” Her sister’s tone was flat, merciless. “Perhaps the time has come to hasten...”

“I didn’t—I couldn’t—I’d never dream—” Arsinoe stuttered through these lies. She had dreamt of it; she’d dreamt of so many deaths over the years. Some had come to pass, and some had not— though, she thought wryly, sooner or later they all would. Everyone died, even Ptolemies.

“I know that you have suffered, but let the past remain the past. Surely somewhere in your heart you might find some tenderness for our father...” Cleopatra’s voice, melancholy, drifted off, as though what saddened her most was that Arsinoe hadn’t shared in the Piper’s love. Arsinoe bristled. She didn’t want her sister’s charity.

“My tenderness extends beyond our father, Cleopatra, to all of Egypt, to this whole troubled kingdom that one day soon you must rule. A weak king...” She stopped herself. She wasn’t heartless.

“A weak king reaps a weak kingdom,” Cleopatra completed the axiom. “But only fools rely on foolish adages. There will be time for us to right his wrongs. He’s tried, and for now that must be enough. He does love you, Arsinoe.”

Hollow words.

She shrugged Cleopatra’s hand from her shoulder. “His love doesn’t change anything. Not for me, and not for Egypt.”

That night, Arsinoe’s dreams were dark and deranged. The city burned; a vulture, she flew among the flames. She circled lower in her flight to feast upon the corpses. They were but ash and bone, burnt offerings to the gods. Hunger pierced her, and she tried to flee the haunted city, to seek out fish and game along the Nile. But every time she reached the southern gates, the wind turned her; the sky became a labyrinth, a winding maze with no escape. She woke sweating, panicked. A special realm was reserved among the damned for those who killed their kin. What she needed was to blot such thoughts from her head. For the first time in ages, she found herself looking forward to her morning lesson with Ganymedes: at least it might provide some respite from her troubled mind.

But there, too, she was wrong. Amid the sturdy pillars of the library, breathing in the scent of cypress rising off the freshly polished desks, Arsinoe found no solace. Euripides shrieked accusations from the page as she read about Electra’s warped tale of matricide, how Agamemnon’s daughter was drawn to take revenge upon her mother for her father’s murder. Four words ran before her eyes, over and over again. Electra the wretched prays, Electra the wretched prays, Electra the wretched prays...

“Arsinoe,” her eunuch snapped. “Have you even begun preparing for this exercise?”

“Electra the wretched...” Unwitting, she’d recited the words aloud.

The eunuch cleared his throat. “An original speech, Arsinoe. I should hope we were long past the stage where I must test your ability to read.” Ganymedes scratched at one of his bushy, graying eyebrows. “I’ve taught ten-year-olds who listen better. You were one of them.”

Her anger frayed and snapped. How she had listened. She’d always listened. For years she’d soaked in the eunuch’s rules, and what good had it done her? Despite his machinations to keep Arsinoe alive throughout Berenice’s rule, he hadn’t known how to protect her upon the Piper’s return. Instead, he’d abandoned her in the agora and hoped that she would—somehow—survive.

“My father’s dying, Ganymedes,” she hissed. “I should be at his side, as Cleopatra is. But instead I’m here reading about deaths from another age.”

The eunuch studied her with narrowed eyes. “You are too old, Arsinoe, for me to have to explain the differences between yourself and Cleopatra. Your father demands your sister’s presence; he demands I teach you to the best of my ability. When the day comes that I am released from this duty, you can pass your time howsoever you please.”

There was no point, she realized, in arguing. Did she really want to spend another morning by her father’s bed? Watching as he clutched Cleopatra’s hand, wincing as he spurned her own? And so Arsinoe squinted at the page and tried to force the swimming letters to still. Electra the wretched prays; year after year her father’s blood cries from the ground; but no god hears.

Her eyes burned. She couldn’t read this, not today, and no more could she speak words in Electra’s defense. After all, their crimes— Electra’s real, hers imagined—were too near. Did Ganymedes suspect her? Why else would he have chosen this particular passage on this particular day? But I’ve done nothing; we merely spoke...

“What wretched sights have cursed my eyes!” The howl of some common woman: a barefoot peasant in rough-spun grays wandered about the reading room, weaving demented circles around the scholars’ desks. She must have slipped by the guards. “A weak ruler and a weakened land, a pair of Romans ripping apart both land and sea, Egypt come to ruin, drowning and aflame.”

Wild-eyed, this rogue prophetess launched herself onto a bench. It wobbled beneath her weight but held. The nearest scholar, a squat, bearded man, furled his scroll and hurried off as though her rages were contagious. The creature hoisted her skirts and, with surprising grace, hopped onto the writing table. Hands tearing at her hair, she cried, “Apollo, lord of light, healer of Delos, guard of the hunt, have pity on your priestess! Let these men, these learned men, hear and heed your warnings!”

Two guards emerged, spiders from the woodwork. But the seer paid them no mind. Arsinoe pitied this creature; they shared the same curse of foresight. Run, she mouthed, though she knew the woman couldn’t hear her. Run and hide, for they will find you and they will seize you and they will kill you.

“Many have already fallen to the Republic that blights our land, to the wolf who nurses traitors at her teat, to the eagle screeching across the sea. And many more shall fall. When a king falls ill, his kingdom falls ill with him. And when the king lingers so long near death—”

Already the soldiers were upon her, toppling chairs as they dragged her from the table. But they couldn’t silence her shrieks. And the shrieks, Arsinoe knew, were where her power lay.

“The city burns to the ground, under the warped guidance of an old and dying man! Blood, the blood of babes. Set upon by the Furies, women devour their own young—Oh, Apollo! This is too much to bear—”

A hand sealed the woman’s mouth. She flailed and bit like a netted stag. Arsinoe found herself mesmerized by the spectacle; she could not avert her gaze. But she was the only one staring. The scholars busied themselves with their scrolls, looking in any direction save at the woman screaming in their midst. Even the one who’d dashed off in fright had already righted his overturned chair and resumed his study.

“I thought curiosity fitting for learned men,” she whispered to Ganymedes. “But these ones barely bat an eye when a prophet spits fire in their faces.”

“Perhaps you’ll learn something from their focus.” The eunuch’s tone was severe, but she detected the double meaning in his words. The liveliest facet of a room was rarely the most informative. Her eyes fixed first on the squat man at the cursed table; she could not make out his notes precisely, but they were of a different character than the ones that had come before. He’d been sketching lines and angles and equations, but now he scrawled row upon row of words. She caught a phrase—the blood of babes—among them. His disinterest was feigned. The silence marked not ennui but rapt attention.

A fist thudded on the door. Arsinoe rushed to open it: in the darkened antechamber, her sister looked a fearsome vision. Her hair wild and loose, she might have passed for the morning’s prophetess.

“Were you there when it happened?” Cleopatra whispered. Beyond, on the divan in the antechamber, Arsinoe saw her maid lying too still for slumber. She hurried Cleopatra into her room.

“Was I where?”

“In the library, when the soothsayer snuck in from the streets.” Moonlight from the window cast Cleopatra in a ghostly haze.

“I was,” Arsinoe answered slowly. “I was studying with Ganymedes. What difference does it make?”

“Did you believe her words?”

“Which ones?” Arsinoe forced a laugh, lightness to counter Cleopatra’s gravity. “That the city shall burn? Or that women will eat their babes?” Her own dream flickered before her eyes. There, too, Alexandria had been consumed by flame.

“Be serious.”

“Why? You surely aren’t. You don’t even believe in seers.” Her nerves grew taut.

“It doesn’t matter what I believe. The whole city is buzzing over her predictions. And Father does nothing. He won’t listen to me when I tell him that he must.” All at once, Cleopatra’s toughness faded, and a petulant child stood in her place.

“But what can he do?” Arsinoe asked softly. “He’s too ill to even leave his chambers.”

“We must find a way.”

“A way to what?” she echoed, though she knew what Cleopatra had in mind, the idea she herself had planted there.

“Don’t play the fool.” Cleopatra’s eyes, wide and desperate, bored into hers. Arsinoe looked away—she couldn’t bear to see the horror she had wrought.

“Fine,” her sister went on coldly. “Must I spell it out for you? You were right. It’s a dangerous time. Dangerous for all of us. Rome rises each day with a hunger. A weak ruler won’t survive, especially not once the people lose faith in him.”

Her own words flung back to haunt her. Cleopatra, father-loving Cleopatra...even her devotion could be spoiled. Arsinoe felt a great cavern open in her chest. The dark and damaged part of her soul had longed for this cleaving, this shaking free of their father’s yoke. To place Cleopatra on the throne, to forget the man who’d allied himself with Rome and murdered Berenice. To bury him.

“There is...” Her voice trailed off, and she swallowed. Now, she knew, she must be brave. “You know the way as well as I.”

“I want you to say it.” Not a request but a command.

“What is it that you drip each morning into his wine?” Arsinoe’s voice sounded a thousand stades away.

“Opium to thin the blood and dull the pain.”

“And doesn’t his doctor sometimes prescribe another drug?” She recalled the physician crushing leaves with a pestle, the bitter stench of poison stinging her nose. “A drug that soothes his limbs?”

“Yes, he does. Father says he feels almost well enough to rise after he has a sprinkle of hemlock.” Cleopatra held her gaze.

“It’s a delicate plant, hemlock. You must be very careful with the dose.”

“I always am.”

“For if your hand should slip...”

Cleopatra’s eyes fell to her feet. Silence spun out between them. Even as they danced about an understanding, Arsinoe felt her sister’s disgust congealing into hate. If they sinned in this together, would that loathing ever fade? Arsinoe broke: “I didn’t mean—the things I said—”

Her sister stared at her: Delicate eyes sharpened with a newfound strength. A firmness of resolve. “The things you said were right. It should be done at once.”

Arsinoe dug her fingernails into her wrists to keep from weeping. Her heart ached for Cleopatra, the glory of her father. Cleopatra, whose very name spoke to their differences in the king’s eyes.

“I—I could prepare his medicine some nights,” Arsinoe said quietly. “You take too much upon yourself...You need your rest.”

Cleopatra stepped forward and embraced Arsinoe. “No, my dear,” her sister whispered, “I must do this. I alone.”

By the time Arsinoe put out her lamps and curled into bed, she had begun to wonder if it had all been some twisted dream. Had Cleopatra truly spoken to her of murder? Or had some evil shadow taken on her sister’s aspect, a god-sent vision to warn her of the horrors to come? Or perhaps Cleopatra had merely meant to tease her, to make some great joke of the strangeness that had passed between them. Perhaps, in the morning, her sister would laugh. You believed me, I know you did, Arsinoe! As she had when they were young. And yet— she’d seen something sinister in her sister’s gaze...

Arsinoe shut her eyes and pushed away her foolish thoughts. That was the child in her, the one who imagined every corner was full of portents. Ganymedes always told her she should fix her mind instead on the unyielding world, the steady pulse of day-lit truth. And so she would.

This excerpt from The Drowning King copyright © 2017 by Emily Holleman

She soared over the city, parched and desolate. Commoners writhed and withered on the boulevards. Rats scurried past their parents’ corpses toward the dearer dead. Dipping between the temples, she traced their path. Alexander the Conqueror, stern in deathless marble, loomed, his sword thrust in the air. Blood leaked from his eyes, his lips, his thighs. The children cupped their greedy hands to drink.

“Arsinoe.”

Wings stretched against the sun, she sailed onward, over bright sands, far from the arid Nile and its sins. Her feathers bristled in the breeze. The desert flamed beneath, and then folded to the sea.

“Arsinoe.”

Thirst stung her throat. She circled down, toward the crashing waves. Her beak snapped against the salt.

“Arsinoe, my sweet. Awake.”

She did not fly over the wine-dark sea. She lay small and shivering in her bed.

“Another night terror?” A gentle hand wiped damp hair from her brow.

Eyes sealed, Arsinoe clung to the wisps: her wings spread over the sands, the sticky seawater on her tongue. Had it been a tongue? Or did vultures taste by other means?

“No, it was… not a terror, no.” She was nearly nine. Too old for fears that came at night.

“You could’ve fooled your old nurse.” Myrrine clucked.

Arsinoe opened her eyes. Her nurse perched at the end of the bed, a few wisps of hair escaping her customary bun. With her full cheeks and unlined eyes, the woman had long preserved an almost ageless air—but now Arsinoe noticed the flecks of gray gathered at her temples. Beyond, the room was calm. The sewn muses danced about her walls in reds and golds, her silver basin brimmed with water, her clothes smoothed out for the coming day. But something was wrong. The light pouring through her windows was brash and dazzling. It was late. Long past dawn. She must have slept through the early hours. And on this day, this day—

Arsinoe sprang up from her bed. Her legs were weak and wobbly, as though her

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Cleopatra's Shadows

Emily Holleman

Jump to a genre

Unlock full access – join now!

OrBy signing up, you agree to our Terms of Service, Talk Guidelines & Privacy Policy

Have an account? Sign in!