- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

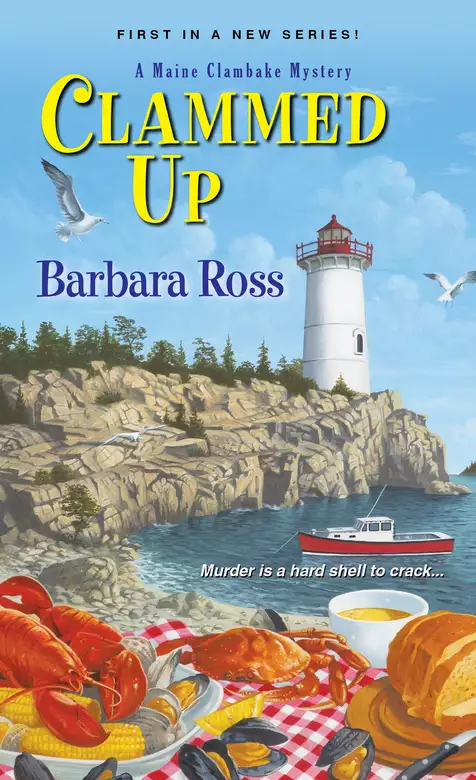

Summer has come to Busman's Harbor, Maine, and tourists are lining up for a taste of authentic New England seafood, courtesy of the Snowden Family Clambake Company. But there's something sinister on the boil this season. A killer has crashed a wedding party, adding mystery to the menu at the worst possible moment . . .

Julia Snowden returned to her hometown to rescue her family's struggling clambake business—not to solve crimes. But that was before a catered wedding on picturesque Morrow Island turned into a reception for murder. When the best man's corpse is found hanging from the grand staircase in the Snowden family mansion, Julia must put the chowder pot on the back burner and join the search for the killer. And with suspicion falling on her old crush, Chris Durand, the recipe for saving her business and salvaging her love life might be one and the same . . .

Release date: September 1, 2013

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 385

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Clammed Up

Barbara Ross

“Julia. Turn. The Boat. Around,” the bride, a willowy brunette named Michaela, demanded.

I shook my head. “Not a good idea. We’ve discussed this. We’ll get to the island and unload the food. Then the boat will head right back to the harbor.”

My eyes swept the deck, searching for the maid of honor. Wasn’t calming the bride her job? But she was off in a corner of the stern with the bridesmaids, gossiping vigorously. I knew exactly what they were talking about. The best man wasn’t onboard. Neither was the groom.

Back at the dock, when the best man hadn’t shown up at the appointed time, there’d been some nervous joking. The night before, after the rehearsal dinner, a group had gone out to Crowley’s, the noisiest tourist bar in Busman’s Harbor, and evidently, the best man had gotten pretty hammered. Nobody remembered walking him to his hotel. He must have been the last member of the wedding party left in the bar.

As time had ticked by, his continued absence wasn’t so funny. His hotel door had been pounded on. His cell phone had been tried, though service was pretty spotty in the harbor. I called from my phone, which would at least get a signal, but his end went straight to voice mail.

“We have to get going,” I’d finally told Michaela. “If we don’t get the food over to the island soon, you’ll have a lot of hungry guests.” The hold of the Jacquie II was filled with live lobsters, clams, and sweet corn that still needed to be shucked so only one thin layer of husk remained.

Michaela had agreed. “Julia’s right. Ray can take the later boat with the guests.”

The groom, Tony, who up to then had been relaxed and smiling, shook his head. “You guys go along. Get to the island, get settled, fix your hair, or whatever it is you’ve gotta do. I’ll find Ray and bring him on the later boat.”

“But—” Michaela had started to protest, but then the reality of the situation hit her.

The other groomsmen were her teenage brothers. Tony’s father was slightly disabled by a stroke and Michaela’s dad had died years before. The ancient minister wasn’t up to searching the harbor. Michaela’s mother, Tony’s mother, and the bridesmaids were already dressed and in high heels. The rest of the passengers included the DJ and my crew, the cooks, waitstaff, and general helpers who made the clambake run smoothly. As far as I knew, none of my folks had ever seen the best man. There was really no one but the groom who could look for him.

“Don’t worry.” Tony kissed Michaela on the forehead. “I’ll be there. Ray and I will both be there.” And then he’d walked down the gangway and off the dock.

At the time, I’d thought Michaela took it pretty well, but now she had a wild look in her eyes and seemed perilously close to a meltdown. To anyone watching, we must have looked like quite a pair. We were the same age, thirty, but Michaela was tall, exotic-looking, and already dressed in her beautiful gown. I was blond, small and wiry, and wore my new uniform of faded jeans, work boots, and a sweatshirt. I’d thought about dressing differently in honor of the occasion, but putting on a clambake was hard, physical work. Thank goodness I’d kept up my gym membership for the nine years I’d lived in Manhattan.

I’d known Michaela vaguely, years ago, as a friend of a friend in New York City, but we’d never been close and I didn’t know what to say to her now.

From across the deck, my brother-in-law Sonny made a face at me that simultaneously said Now look what you’ve got us into and I told you so. I rolled my eyes at him.

Back in early spring when I’d explained my idea to “expand” the Snowden Family Clambake business—I’d deliberately avoided the inflammatory word save—by adding private parties, company picnics, weddings and the like, Sonny was dead set against it. And when I told him private catering would require an expanded menu, he’d lost it.

“The bake is the bake!” he’d yelled. “Twice a day we haul two hundred tourists out to the island, feed them steamers, lobsters, corn, potatoes, an onion, and a hard-boiled egg, all of which we cook in a hole in the ground, the same way the Indians taught our Puritan forefathers. The Maine clambake is sacred. Don’t mess with the bake!”

“Sonny, Indians didn’t start the bake. My father did. In 1979. And since the economic crisis, there aren’t two hundred tourists on that boat twice a day. Sometimes there are fewer than two dozen. In Maine, we’ve got exactly four months to make our money. Four months. So if you think I’m going to stand by and lose my father’s business because you can’t be flexible, you’re wrong!”

We’d retreated to our separate corners, knowing we’d be going a few more rounds. Sonny was more right about some of it than I was. My father had started the Snowden Family Clambake Company, but he certainly didn’t invent the clambake. As to the Native Americans, we knew they ate a lot of shellfish, as shown by the giant, prehistoric piles of oyster shells called middens just up the road in the Damariscotta River. And we knew the Puritans ate lots of clams, or even more would have died during those early winters. But the rest was as much mystery as history. One thing I was sure of. The Indians didn’t teach Sonny’s Puritan forbearers how to do a clambake. If his ancestors were anything like him, no one could teach them a damn thing.

Just as Morrow Island came into view, the maid of honor, whose name was Lynn, finally woke up to her duty. She gently pried the bride off my arm and walked her to a seat. “Ray is just a jerk,” I heard Lynn say, but Michaela shook her head no.

I rubbed my arm to restore the feeling to my tingling fingers, moved to the bow, picked up the cable, and got ready to land.

Morrow Island. I still couldn’t believe Sonny had almost lost it. The island had been in my mother’s family for a hundred and thirty years. It was a great piece of rock, really. Thirteen acres, with good deep-water dockage, and that rarity in Maine, a small sandy beach. On a high hill at the center of the island stood Windsholme, the summer “cottage” built by my great-great-grandfather at the height of the Gilded Age.

As our captain maneuvered the Jacquie II into dock, the island’s caretakers, Etienne and Gabrielle, hurried to meet us. The mansion was abandoned during World War II, when no one had servants to run the place or fuel to get there. The family money was long gone by then, anyway. After the war, my grandfather built a modest house by the dock. That’s where my mother had spent her summers, and where she’d fallen in love with the boy from town who delivered groceries in his skiff.

Now Etienne and Gabrielle lived in the little house all summer. Etienne was our bake master, managing the fire pit where the clambake was cooked. Gabrielle ran the kitchen and made the deep-dish blueberry grunt we served to guests at the end of the meal.

I jumped onto the dock. A steady breeze blew from the south and I wished the temperature were a couple degrees warmer for Michaela’s big day. In spite of what the Busman’s Harbor Tourism Board would have you believe, mid-June was still pretty early for coastal Maine. I closed my eyes for just a second and breathed in deep. Etienne had already started the towering hardwood fire that heated the stones to cook the meal. The smell of burning oak, sea air, and a slight tang from the scrub pines clinging to the rocks was Morrow Island to me. No matter where I went or what I did, it would always mean home.

Etienne and Sonny helped the rest of wedding party onto the dock and we started the long trudge up the great lawn toward Windsholme. Constructed in stone, in deference to the sea winds, the mansion had twenty-seven rooms, not counting bathrooms, storerooms, and pantries. Inside, it was gracious and unexpectedly airy. The double front doors opened into a three-story grand foyer with a staircase that rose, turning back on itself, all the way to the top floor.

We didn’t use Windsholme for the clambakes, though we allowed guests to relax in the rockers lining its deep front porch. Sadly, the inside wasn’t in great condition and we didn’t want customers getting hurt or lost. But to host weddings I knew there had to be a place for people to dress or fix their hair and makeup. The mansion’s 1920s-era knob and tube wiring had long been turned off. In a fit of optimism, I’d hired electricians to rewire a couple rooms on the main floor to handle modern hair dryers and makeup lights.

As we walked up the lawn, the discussion going on behind me was about the best man, Ray Wilson. He was selfish, irresponsible and immature, the maid of honor insisted. “He had one job to do for this wedding. Show up and bring the rings. And he couldn’t get that right.”

“Ray’s changed,” Michaela responded. “Really, he has. I’m worried about him. Something’s wrong.”

“I’m sure he’ll be here.” I tried to sound confident.

And he was. When I threw open Windsholme’s great front double doors, Ray Wilson hung by a rope around his neck from the grand staircase. Dead.

Of course, I didn’t know who he was then. But I had a strong inkling when Michaela crumpled to her knees, shrieking, “Ray! Ray! Ray!” Instinctively, I herded the guests outside and slammed the door. I could tell there was nothing we could do for that poor man.

Once we were back on the porch, I couldn’t catch my breath. My heart banged in my chest as adrenaline surged through my body. I was responsible for these people and for Morrow Island. I took a deep gulp of air to steady myself, then hollered for Sonny and Etienne.

They were down by the fire which makes its own noise, but by the third bellow they heard me and came running. After Sonny took a quick look inside, he and I had a whispered argument about who to call. The Busman’s Harbor Police, the State Police, the harbormaster, the Coast Guard? We decided to call Busman’s Harbor PD and let them sort it out.

Sonny ran back to the Jacquie II to raise the police department via the radio. He also radioed his wife, my sister Livvie, who worked in our ticket kiosk, so she could let the wedding guests know the boat wouldn’t be coming back any time soon.

I ordered everyone back aboard the Jacquie II. They couldn’t be in Windsholme or roaming around the island, so the boat seemed like the best place to keep the wedding party and our employees confined. Once aboard, they clustered as Maine people do in the summer—locals to one side of the top deck, people “from away” to the other—both groups talking like mad. Several got out their cell phones, wiggled and jiggled them, and held them to the sky in the direction of some imaginary satellite. The local people knew it was pointless, but they did it, too.

Michaela sobbed, her mother and the maid of honor on either side of her. I felt terrible. This was supposed to be the happiest day of her life and now no wedding would take place. And she must have so wished Tony was with her during this awful experience. But he was stuck in the harbor, just as we were stuck on the island.

The first person to arrive was Jamie Dawes. I have never been so happy to see anyone in my life. Jamie and I were best buds as children. Until I went away to boarding school, we waited for the bus together every day, and we worked together at the clambake every summer through high school and college. In the few months since I’d been back in town, I’d been so buried in work I hadn’t reconnected with him. According to my mother, over the winter, he’d been appointed full-time to the Busman’s Harbor Police Department.

An officer I didn’t know steered their borrowed motorboat. Jamie jumped out before it stopped moving and I ran to meet him. He put a hand on my shoulder and looked directly into my eyes. “Are you okay?” He was tall and broad through the chest, but he still had the same blond hair, sky-blue eyes, dark lashes, and open, expressive face he’d had as a boy. I swallowed hard and nodded yes.

We walked up the hill to Windsholme and Jamie and his partner went to take a look at the body. They were only inside a few minutes. When they returned, Jamie signaled for me, Sonny, and Etienne to gather around him. “We have to call in the medical examiner and the state police major crimes unit,” he said in a low voice.

“Major crimes! Surely the poor man killed himself.” I said it because I wanted to believe it.

“You don’t know that, Julia,” Jamie responded. “It’s an unattended death with a boatload of question marks around it. Officer Howland and I will stay on the island to secure the scene.”

It didn’t matter to me why Jamie was staying, I was just glad he was. He knew us and he knew Morrow Island and that’s what counted.

Four more members of Busman’s Harbor’s police department arrived to help. The town only had nine sworn officers, and four of those were part-time. Two state police detectives arrived an hour or so later, hitching a ride out with the harbormaster. The medical examiner came on a commandeered lobster boat. Our island looked like it had been invaded by a tiny, mismatched flotilla.

The detectives and medical examiner went up to Windsholme. It felt like we waited for hours, though I was sure it wasn’t that long. Sonny banged around the Jacquie II in a barely concealed rage. “Weddings,” he muttered under his breath, as if holding wedding receptions at a clambake was the craziest idea anyone ever had. And then louder, “I hope you’re happy.”

Happy? I wasn’t even supposed to be there. I was in Maine because of a panicked call from my sister Livvie.

In January, Livvie intercepted a call from the bank to her husband Sonny, who’d run the clambake for the five years since Dad died. The bank was calling our loan. Not only could we lose the clambake, but Sonny had persuaded Mom to put up her house in town and Morrow Island as collateral on the loan. We could lose it all.

“Livvie, how could you let this happen?” I’d yelled into my cell phone.

“I didn’t let it happen. Mom is a mentally competent adult. It’s her property. She can do what she wants!”

I let it go. There was no point in fighting about it by then. The money, borrowed during good economic times, was long gone, used to rebuild the dock, outfit our ticket booth for online sales, and replace the slate roof on Windsholme, which was desperately in need. Slate roofs were incredibly expensive and any work you had done on an island cost three times more.

Then the stock market crashed and the recession hit. The first summer wasn’t so bad. Lots of people canceled flying vacations to take driving vacations and Busman’s Harbor is a day’s ride from the most densely populated part of the country. But the second summer was a disaster. Driving vacations turned into stay-cations and to top it off, the weather was awful. In the harbor, restaurants and inns were half empty. Most of the art on the walls in the galleries and the clothes on the racks in the shops were the same ones at the end of the summer as were there at the beginning. The next two summers weren’t any better. No one was spending money and the Snowden Family Clambake Company was dying.

Livvie begged me to give up my venture capital job and my life in Manhattan to come home and run the business with Sonny. “You’re trained for this. You went to business school. Helping entrepreneurs is what you do. Julia, please. I don’t know what’s going to happen to us.”

I promised Livvie I would give it one summer, which was all the bank had agreed to anyway. In March, I’d moved back to Busman’s Harbor.

Happy. What a concept. I didn’t respond to Sonny. I’d had enough experience this spring to know it wouldn’t be productive. I tried to keep the guests and employees calm . . . and I waited. Finally the detectives emerged from Windsholme and made their way down to the dock.

“Who’s in charge here?” the older of the two yelled up at the boat.

I glanced at Sonny. The question went straight to heart of the issues between us. When he didn’t say anything, I stepped forward. “I am.”

“Where can we go to talk?”

I led the state cops through Gabrielle’s pin-neat kitchen to the front room of the little house by the dock. It had always been a comfortable place for me, cozy inside with views to Spain out every window. I sat on the window seat with my back to the view. The detectives pulled straight-backed chairs from the dining room and sat opposite.

“I’m Lieutenant Jerry Binder, Commander, Major Crimes Unit.” He had a bald spot stretching in a narrow strip from his forehead to his crown. Right away, I liked that he didn’t attempt to disguise it with some elaborate comb-over or shaved head. I sensed in him the same straightforwardness of character he displayed with his hairstyle. The fringe of hair he did have was medium brown with flecks of gray. The round brown eyes staring out over the ski-slope nose showed just a few wrinkles. I put him in his mid-forties.

“This is Detective Tom Flynn,” Lieutenant Binder said. Flynn was younger, early thirties I thought. He had the kind of body that only comes from hard work at the gym. Unlike his partner, Flynn had plenty of hair follicles, but the hair itself was cut so short I only had an impression of its sandy color. He had a New England accent, though it wasn’t quite Maine. Boston, or maybe even Providence. He sat with his back ramrod straight. The whole package—the hair, the posture, the toned body—said ex-military to me.

Binder was polite, even empathetic. He asked me about the island and the business. “Tell me about finding the body.”

I described step by step what had happened. Was I apprehensive when I threw open Windsholme’s heavy front doors? I couldn’t have been. But in the movie in my head, I hesitated, hand on the doorknob, knowing what awaited me.

“What happens next?” I asked when we’d finished.

“We’ll question everyone here and then let you take them back to the harbor,” Detective Flynn said. “From what you say, we should talk to this Etienne person next. Two of our colleagues are with your sister on the mainland. They’re getting information from the wedding guests. We’ll take their contact information and let them go back to their hotels. Same with these people here. Another officer in the harbor is talking to the groom right now.”

The groom. Poor Tony. Not only had he lost his wedding day, he’d also lost his friend.

“Is there any chance Ray Wilson could have done this to himself?” I asked, because more than anything, that was what I wanted to believe.

“Doesn’t look like it,” Lieutenant Binder answered. “Preliminarily, the medical examiner thinks he was hung up there after he was dead.”

I’d only looked at the body for a few seconds, but I closed my eyes and let myself see what my mind had been denying. The dried blood covering the front of Ray Wilson’s pink polo shirt. “Is that where the blood came from? From when he died?”

Neither of them answered. Flynn brushed imaginary lint from his trousers.

I cleared my throat and asked the question I’d been dreading. “How long will we be closed?” I felt selfish asking. A man was dead. But the future of our business depended on the answer.

“No way to know,” Flynn said.

Binder followed, a little more sympathetically. “Certainly you’ll be closed tomorrow. After that, it’ll be day-to-day.”

The Snowden Family Clambake was teetering on the brink as it was. Every day we were shut down would bring us closer to financial ruin. And to losing the island—which I was convinced would break my mother, still recovering from m. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...