- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

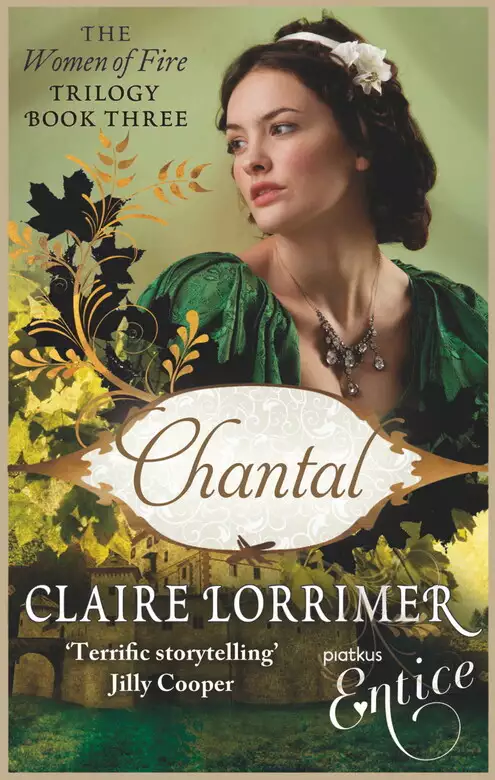

Synopsis

Stubborn in her loyalties and passionate in her affections - Chantal is exquisite, beguiling and volatile. And it is her spirited nature that could all too easily lead the young girl astray . . . Beautiful and alluring, Chantal is adored by three men who will all risk anything to win her love. Torn from the dazzling salons and glittering balls of aristocratic London, Chantal finds herself caught in a gathering maelstrom of wild and dangerous adventure. From a mysterious chateau, to a deserted tropical island, she is swept into a whirlwind of scandal, anguish and ecstasy.

Release date: December 1, 2011

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Chantal

Claire Lorrimer

CHANTAL, natural daughter of Sir Peregrine Waite.

JOHN DE VALLE, son of Scarlett.

SCARLETT, LADY WAITE, stepmother of Chantal.

SIR PEREGRINE WAITE (alias Gideon Morris), her husband.

DICKON SALE, Scarlett’s childhood friend and servant.

ROSE SALE, his wife.

ANTOINE DE VALLE, natural son of Scarlett’s former husband Gerard de Valle, deceased.

STEFANO, Antoine’s servant.

ANTOINETTE VON EBURHARD, Scarlett’s daughter.

CHARLES VON EBURHARD, her husband.

RICHARD

)

WILLIAM

) their children

LISA

)

CLARISSA

)

BARONESS LISA VON EBURHARD, Charles von Eburhard’s aunt.

ANNE LADE, friend and sister-in-law to Scarlett through her second marriage.

JULIA LADE, her daughter and Chantal’s friend.

DOROTHY, Chantal’s maid.

DORCAS, Scarlett’s maid.

ELSIE, Antoinette’s maid.

DUC DUBOIS, French aristocrat and friend of John’s.

DUCHESSE DUBOIS, his wife.

FLEUR DUBOIS, their eldest daughter.

AIMEÉ

)

ROSE

)

JEANNE

) their other daughters.

SUZANNE

)

NOELLE

)

LUKE, John’s servant.

PRINCESS CAMILLE FALOISE (alias MARIE DUVAL), Antoine’s guardian and wife.

CAPTAIN ANSON, Captain of HMS Valetta.

THOMAS LOVELL, 1st Lieutenant of HMS Valetta.

KAFTAN, Lascar sailor on HMS Valetta.

DINEZ DA GAMA, Portuguese pirate and captain of O Bailado.

MIGUEL, First mate of O Bailado.

ZAMBI, African slave-girl.

SIMÉON ST CLAIR, Plantation owner on the island of Mahé.

NARCISSE, Siméon’s African housekeeper.

TOBIAS, her husband and Siméon’s foreman.

ROSE PRINTIÈRE, their daughter.

MATHIAS, her fiancé.

JEROME

)

FABIES

)

GASPAR

)

MOSES BEMBA

) freed African slaves on

FIGARO

) Siméon’s plantation.

JOLICOEUR JUSTIN

)

ZEPHIR VOLANT

)

AZOR LAFLEUR

)

JACK CLIFTON, Captain of Jason, a convict ship.

ADMIRAL PENTELL, British Naval officer at Admiralty House.

SMITHERS, his clerk.

HAMISH MCRAE, Captain of Seasprite.

PAUL MYLIUS, younger brother of the Civil Commissioner on Mahé.

JANET

)

his daughter

PHOEBE

)

PIERRE, young French messenger.

BLANCHE MERLIN (alias MARIANNE), Antoine’s mother.

FRANÇOIS NOYER, a prisoner.

Of necessity historical novels are a blend of truth and fiction. It is remarkable how frequently the adage “Fact is Stranger

than Fiction” proved to be the case while researching. It was intriguing to discover a book in the British Museum by a Major

W Stirling relating to the fate of the HMS Tiger in 1836 in which her survivors did reach the safety of the Seychelles island of Astove. The survival of members of the fictitious

frigate HMS Valetta is based on fact.

The story of Chantal is based on the following true facts:

The town of Compiègne with its Roman ruins, Palace, Forest, Châteaux all exist, although Boulancourt itself is imaginary.

The existence of the convict ship, Surrey, the Pulteney Hotel, Prince Esterházy de Galántha are facts as are all the incidents relating to history, politics, politicians,

royalty, the arts, industry and the law. The laws relating to divorce and legitimacy in France in Chantal’s day are also true.

Strange though they may seem, so are the mishaps at Queen Victoria’s coronation.

The island of Coetivy, named after the Chevalier de Coetivy who first sighted it in 1771, exists as does Mahé, these being

two of over ninety islands in the Seychelles Archipelago. Place names prevailing on Mahé during the period of the story have

been used in preference to those currently in use. The existence of pirates in the area, the trading of slaves and their treatment are historically correct. The names of slaves in CHANTAL

are taken from an original slave register.

The incarceration of Antoine de Valle’s prisoner in CHANTAL is similar in nearly every respect to that of a lady who lived

in England in the nineteenth century. There are documents recording her imprisonment and death. The interesting point here

is that when the real prisoner was discovered, she was naked, wearing only a red wig! This is fact and not fiction, but to have included such details

in CHANTAL may have stretched the reader’s credibility too far.

I am greatly indebted for help received from:

Croydon (Reference Section), East Grinstead and Edenbridge Libraries.

M. Lucien Mourgeon (Avocat).

Mr Gilbert Pool (Tourism Director for the Seychelles).

Mr Nirmal Kantilal Shah (Mahé).

British Maritime Museum (Greenwich).

British Museum (Library).

Institut Français du Royaume Uni (Bibliothèque).

Joy Tait, Sandra Clifton (Research).

Penrose Scott, Gill Ayr (Secretarial).

Mr Malcolm Paisley (Photographer) for family documents.

March 1821

On the 8th of March, 1821, the woman died. The four-month-old child in her arms wailed fitfully as her mother’s body froze

in the bitter night air, waking the exhausted man huddled beneath his cloak nearby.

Gideon Morris, known to all but a handful of people as Sir Peregrine Waite, was roused from sleep to the bitter discomforts

of cold, hunger and a renewed awareness of the throbbing pain of the half-healed wound in his leg.

“Maria,” he called gently, “the child is hungry and needs feeding!”

He reached out a hand to the hunched figure of the young woman lying beside him in the bitter night air.

The stiffness of her body brought him fully awake. As the baby’s crying intensified, a sudden fear that the mother was dead

made him hesitate to touch her a second time lest that fear was proved justified.

“Maria!” he called again, this time urgently.

He was deeply shocked and distressed to realize she was dead although this tragedy was not altogether unexpected. He had never

loved the young Neapolitan woman in the way he knew a man could love the woman of his dreams, but he had nevertheless felt a deep affection for Maria. For all she was but a simple

peasant without breeding or education, her loving devotion to him these past twelve months had earned his gratitude and respect.

Not only had she proved courageous and loyal, but her nature was essentially passionate and caring.

As the child’s wails became weaker, Perry’s stunned immobility gave way to action. With difficulty he prized the baby from

her mother’s stiffened arms. The minute face was pinched and blue with cold. Hurriedly he unbuttoned his thick cape and the

jacket beneath, and removing his pistol, pressed the small body close to his chest where his own body heat might impart some

warmth to it. At once the tiny hands began to search instinctively for the mother’s breasts, the hunger in her little body

of overriding concern.

With a renewed sense of shock Perry realized that the woman’s death would almost certainly result in the death of the child.

It had not been weaned and the chances of his finding a wet nurse here in the mountains of Italy were highly improbable, even

had he the money to pay for such services.

It was now over a week since they had left the comparative safety of the encampment in the hills above Potenza. They had lived

there with other members of the resistant force called the Carbonari ever since he had led them into hiding after an uprising

against the Government in Naples nearly a year ago. The uprising had failed and they had been chased into the hills. Perry

was so severely wounded that had it not been for the care of these poor peasants he would certainly have died. The men, driven

by poverty and a burning sense of injustice, were in war-like mood and anxious, as soon as he, their leader, showed signs

of recovery, to renew their resistance. But most had lost their weapons and there was no money to buy more. From his sick

bed, a straw palliasse on the floor of a shepherd’s hut, Perry dispatched a messenger to Pisa with a written request to his

friend, the poet Percy Shelley, to send funds. He had given Pietro his last remaining valuable – his gold watch, with which to guarantee his authenticity to the Shelleys.

For several months the small band of Carbonari waited, living on the meagre rations supplied by the poor people in Potenza

who were themselves close to starvation. Maria nursed Perry, attending to his dreadful wound as best she could. She was a

dark-haired, comely young woman approaching thirty and already widowed, her farmer husband having been killed in an earlier

uprising. The intimate bond between nurse and patient deepened as Maria’s passionate nature revealed itself. When in an unguarded

moment, she shyly declared her love for the handsome English aristocrat, the essence of their relationship changed and they

became lovers. She was never in doubt about the true nature of their association.

“I know we cannot be married – it would not be right for a titled Englishman to wed a Neapolitan peasant girl!” she had said

in her simple, direct way. “But I love you – io t’amo – and I know that you need a woman. I want you to take me even if you cannot love me.”

Perry had not resisted her for long. He had come to Italy for the very purpose of forgetting the one woman in his life he

could ever love or marry – Scarlett, now the wife of the Vicomte Gerard de Valle.

Not a night passed that he did not think of her, long for her, wonder whether she was happy now that she shared her life with

the man she had loved for so long. He hoped that perhaps with Maria’s soft arms enfolding him, his dreams might at last be

haunted less often by his memories of the passionate love he had once known with Scarlett.

When Maria told him she was with child he had received the news with deepest misgivings. The privations of their lives in

hiding in the hills were extreme and in any event he had no wish for a child, far less an illegitimate offspring for whom

he could not disclaim responsibility. But for the sake of the woman who cared for him so selflessly, he tried to hide his

reaction. Maria was clearly proud and delighted to be bearing his child. When the babe was born in the early hours of a chill November dawn,

he had allowed her to believe that he, too, was delighted as she placed the tiny girl in his arms.

“We could call her Maria after me or Lucia since she was born at break of day,” the proud mother had whispered. But Perry

was unable to share Maria’s pride or radiant joy and gave no thought to the baby’s naming.

One by one the men began to return to the farms which they had left to join the Carbonari, for it was becoming clear to them

all that the messenger, Pietro, had never reached the Shelleys and no funds would be forthcoming. Word came from other members

of the Carbonari that resistance was weakening and that their cause no longer justified the neglect of their farms and families.

By the end of January all had left the encampment and Perry, too, would have departed but for the unhealed leg wound which

forbade walking any but the shortest of distances.

For a while he contemplated sending Maria into Naples to see the British Consul, Sir Henry Lushington, to ask for aid since

he was, after all, a British subject. But he feared for her safety should she be recognized as an associate of the Carbonari.

Her former husband had been well known to the authorities and he dared not risk her recognition.

“We will remain here a while longer,” he told her. “You, too, need to regain your full strength. By March the weather will

be better. Then we will make our way north where my friends are living. They will care for you and the baby.”

But he had underestimated the seriousness of his leg injury which, despite Maria’s care, had not healed properly, for splinters

of bone were still buried deep within his thigh. With unwelcome frequency abscesses occurred and he was seldom without fever

and pain.

The child thrived on her mother’s milk, but Maria tired quickly and was clearly losing weight as they began their travels

northward. They survived on the rabbits Perry snared, a skill he had learned in his youth when he had first had to live on his wits. Occasionally a farmer would give them milk, but often

they were turned away because they had no money to pay for their requirements. The milder Spring weather was late in coming,

and the bitterly cold nights with only the roughest of shelters to keep out the winds, added to their misery and ill health.

To Perry it was clear now that Maria had kept from him the true state of her weakness. Rather than be a burden, she had walked

beside him uncomplainingly until he, himself, had given in to weariness and pain. With the child needing food every four hours

or so, Maria’s strength ebbed and unrecognized by her, she had developed milk fever.

Perry’s self-condemnation was acute as he closed the lids over her eyes and covered her drawn, beautiful face with her cloak.

But for the child, he thought bitterly, she might have survived; and he felt a moment’s anger as the baby began to wail its

frustration within the warm confines of his jacket. There seemed little doubt that it too must die for he had no means of

feeding it. Perhaps, he thought wearily, it would be for the best. There was no great future for an illegitimate girl, motherless

and with a father who cared not whether she lived or died. Death might be the best solution and the kindest for the baby,

since to die slowly of starvation could only prolong its misery.

With a feeling born partly of exhaustion, partly of despair, Perry reached for the small moist bundle and withdrew it from

his jacket. The shock of the cold air silenced its cries. With miraculous rapidity the crumpled red face paled, uncreased

and became a tiny replica of its mother’s, the petal smooth, creamy-olive skin curving gently over delicate cheekbones. The

long dark lashes, wet with tears, lifted suddenly and two beautiful almond-shaped eyes stared up at him in mute appeal. From

beneath the rough-spun shawl in which Maria had wrapped the child, one small clenched fist appeared, and as the minute fingers

uncurled, Perry noticed for the first time the dainty perfection of the pearl-pink nails.

For the rest of his life, Sir Peregrine Waite was never to forget the magic of that moment when first he felt the full force

of fierce paternal love for his daughter. The awareness of her perfection, of her dependence upon him, of the fact that she

was part of him, overwhelmed him. Tears that he could never have shed for her mother, now filled his eyes as he realized the

baby’s helplessness and frailty. In that same moment, he knew that he could never again contemplate her death; that somehow

he would find a way to save her. He determined that insofar as it was within his power, his love would be large enough and

strong enough to ensure that she would never miss her mother.

As the baby’s cries were renewed Perry faced the need for immediate action. He knew they could not be too far from La Spezia

for they had left the outskirts of Livorna behind them two days since. He should soon find a hill farmstead where hopefully

he could obtain milk for the child.

Lack of food and the poisoning of his blood from his leg wound had brought Perry almost to the end of his strength. Although

it tore at his heart to leave Maria unburied, he knew he must now conserve what energy he had left for the sake of the child.

Limping awkwardly, Perry began his slow journey over the hills. The sun was high in the sky, imparting a small measure of

warmth to his aching limbs, before he first heard the bleat of goats and knew that help was not far off. The baby was silent

now – a fact which increased his anxiety for its hunger pains must be even more acute than his own, and a healthy child would

be protesting volubly. With renewed effort he strode forward and a moment later he saw with a sigh of relief a herd of goats

browsing on the hillside. A lad of twelve years or so was guarding them.

“Buon giorno!” Perry waved from a distance and shouted his friendly greeting a second time. To his dismay the boy neither returned his

greeting nor the wave of his hand but jumped to his feet and menacingly raised the stout stick he was holding.

Perry was well aware that bands of brigands, robbers and outlaws, often starving and very dangerous, attacked such isolated farmsteads in order to obtain provisions for themselves.

Doubtless the goatherd mistook him for one such, ragged and dishevelled as he must appear to the boy. Cautiously, he walked

forward but now the boy took fright altogether and, abandoning his herd, ran like a young hare towards his home.

Wearily Perry followed him the half-mile downhill to the farm only to find the stout wooden door of the little cottage heavily

barred against him. For half an hour he banged upon the door, alternately shouting and pleading for assistance. Either the

occupants did not understand his excellent Italian, which doubtless differed considerably from their own dialect, or they

were too frightened to risk confrontation with a man carrying a pistol.

Perry’s spirits flagged alarmingly as the hopelessness of his position struck him. With the child in his arms, he could not

shoot his way into the house. The next farmstead might be many miles away and even if he could find the strength to walk there,

the baby must be fed soon if it were not to die.

Staring down into the dark eyes, so large in the tiny pinched face, he knew that he could not permit himself to collapse,

leaving them both to the mercy of the farmer. There must, he thought desperately, be something he could do.

As if in answer to his thoughts, the faint bleat of a goat reached his ears. A sudden, secret smile spread across Perry’s

exhausted face. It would not be for the first time in his life if he were forced to resort to theft in order to survive, he

thought. He had but to steal one of the unguarded nanny goats for the child to be certain of nourishment however long it took

him to reach Pisa.

Knowing that suspicious eyes were regarding him fearfully from the grubby windows of the farmstead, he walked away in a different

direction to that of the grazing herd. Making a large detour, he came upon the animals from the far side of the hill. Laying

the baby carefully on the ground, it took him but a few cautious moves to approach the nanny of his choice, secure it with

his belt and lead it away from its companions.

Surprisingly the animal neither struggled to resist him nor called a warning to the herd. Clearly it did not consider Perry’s

gentle handling a danger. He remembered well from his youth how to milk an animal, but the task of feeding the baby with the

liquid he had channelled into Maria’s cooking pot presented a more difficult problem. Necessity aroused his natural resourcefulness.

He dipped his ’kerchief into the warm milk and placed a corner of it into the child’s mouth. It was not long before the starving

baby began to suck. Each time Perry removed the ’kerchief to soak it once more in milk, the wails increased in volume and

despite the gravity of the moment – for this was her last chance of survival – Perry grinned, marvelling at his daughter’s

tenacity and at the huge force of anger contained in so tiny a frame.

Only when she had fallen asleep, totally replete, did Perry take a long draught of milk himself. Far more easily digested

than cow’s milk, the stolen nourishment revived both man and child. Perry watched her for a while, anxious lest she might

have overfed or that the new type of milk might not suit her. But the colour had returned to the baby’s cheeks and she slept

quietly and happily, not stirring when he lifted her into his arms. He resumed his walk, the nanny goat trailing behind him.

In such a manner Perry and his daughter reached the safety of Rome where he was able to seek assistance at the British Consulate.

There he was given fresh clothing for himself and the child, money to suffice for his needs, a carriage to take him to Pisa

and a wet nurse to accompany them. The goat was left at the Embassy. To the secret amusement of the residents, Perry insisted

that it should not be sold but be allowed to live out the rest of its life in the Embassy gardens.

“After all,” he told his host, “the animal saved my daughter’s life!”

As April drew to a close, the small party arrived at Pisa to be greeted by the astonished but delighted Shelleys.

“We had word that you were dead, my dear fellow!” Percy said, looking curiously at the nurse and then at the bundle in Perry’s

arms.

“This is my daughter and this woman is her nurse!” Perry said smiling. “I am hoping that Mary will care for her, for the child’s

mother is no longer alive.”

“As if you could have any doubt upon it!” Mary cried, peering at the child in his arms. She gave a small cry of wonder. “What

a beautiful baby, Perry! How old is she? What is her name? Who was her mother?”

“Let our friend rest a while before you ply him with questions!” her husband suggested, noting Perry’s pallor and guessing

correctly that he was far from well.

He led Perry into the salon where he sank wearily into one of the comfortable chairs, still clasping the child in his arms.

His leg was paining him almost beyond endurance and he was alternately shivering and burning with fever. Yet he gave no thought

to his health as he smiled at Mary.

“My daughter is twenty-two weeks old today. But as to her name, she has none as yet. Her mother suggested we might call her

Maria, or Lucia because she was born at break of day. But during our adventures of which I will tell you presently, I have

been thinking a great deal on the matter.” He turned to his friend and said eagerly, “This is no ordinary child, Percy. Even

at her tender age, she is showing the most astonishing eagerness for life. She has survived where other infants must surely

have died. And unless she is cold or hungry, she is the happiest little skylark in the world.” He turned once more to Mary.

“She warrants a more unusual name than either Maria or Lucia,” he said softly, “something that expresses her joy and enthusiasm

for life; her individuality. Even allowing for the fact that I am her father and you may judge me prejudiced in her favour,

I swear to you she is like no other child!”

“Then we will think of a very special name for her!” Mary said. “But Lucia will suffice for the present. Now I can see you

are sorely in need of rest and care, Perry. Leave the child to me, my dear. I will take good care of your beautiful daughter!”

Reluctant to release his burden, Perry said:

“ ’Tis a miracle she has survived, my friends. I am forced to the conclusion that destiny has some special design for her

since few so young can have suffered so poor a start to life and yet smile so confidently at the future.“

Neither he nor his companions realized at that moment how prophetic were Perry’s words and how greatly his child would one

day need that confidence to survive the physical and moral dangers that lay in wait for her.

Happily unaware of the future, Perry allowed the kindly woman to remove from his arms the little girl he was eventually to

christen Chantal.

August 1837

At the head of the thirty-foot-long oak dining table sat a young, fair-haired man. He was smiling enigmatically as he surveyed

the scene before him, his dark eyes narrowed speculatively, his brows raised slightly as if in scorn or boredom.

From the far end of the table, a young Parisian blood lurched forward across his female neighbour, oblivious to etiquette

as he called out in a high, shrill tone:

“Antoine, mon ami, is it not time to let us see tomorrow’s contestants?”

A burst of clapping from forty pairs of hands echoed upwards to the ceiling some thirty feet above their heads. Goblets of

wine were knocked over by waving arms. As the dark red liquid ran from the polished oak surface and stained their clothes,

shouts of protest mingled with cries to their host to satisfy their demands.

Antoine de Valle remained silent, his beautiful aristocratic face impassive as the noise and disorder at his table increased

in volume. Only the imperceptible curve of his finely shaped mouth betrayed a hint of distaste as his eyes went from face

to face, noting the heightened colour of those who had already over-imbibed. Many of the women were drunk as the men. Every one of them was young and liberally endowed with feminine appeal. Demimondaines, they were paid companions of his friends

– the young bloods who could afford to pay for the luxury of smooth, white shoulders, invitingly curved breasts and tempting

mouths.

Their host seemed oblivious to the fact that the morals of these females, like their manners, were as out of place in the

banqueting hall of the Château de Boulancourt as was the disorder of half-eaten foods littering the great table. There were

no servants in attendance. Later, when the diners adjourned to the salle à jeux to enjoy the delights of the gaming tables, servants would be permitted to return to the huge dining-room to clear up the

debris. Antoine de Valle was not, as he might appear to a stranger, impervious to his reputation and once the food had been

brought to the table, no servant who might carry tales was present to witness the orgy of such banquets as these.

“Do not keep us in suspense, mon vieux!” another of the male guests pleaded. “Let us whet our appetites for tomorrow’s entertainment.”

Roughly the man detached himself from the clinging arms of the woman beside him.

“You have not forgotten that proverb you so often quote, Antoine? ‘Satiety of what is beautiful induces a taste for the singular.’

”

A roar of laughter from the men greeted his words. Their female companions shrieked in shrill protest. The noise was deafening.

Smoke from the guttering candles in the many candelabra stretching the length of the table curled slowly upwards, stinging

the eyes of the two young kitchen boys concealed in the gallery high above one end of the room. Both knew that were they caught

espying their masters, they would be thrashed within an inch of their lives and instantly dismissed from service. But curiosity

had this night got the better of them. The scene they surveyed was in no way disappointing. Both were simple-minded village

lads who had heard their elders speak of “ladies” such as these. But no gossip had prepared them for the sight of a bare bosom exposed to view as if it were of no import; far less of a man’s hand idly fondling it whilst he drank

from a goblet, or engaged in conversation with the painted beauty seated on his other side.

Their master suddenly raised his head and spoke. Fear overcame their fascinated curiosity and the boys scuttled off noiselessly

as Antoine de Valle said:

“Since you insist, mes amis, I will have the gladiators brought in!”

A vast cheer greeted his announcement. He rapped loudly upon the table top to summon his personal servant, Stefano. The man,

swarthy and Italianate in feature, hurried into the room. He bowed and bent his head close to his master’s.

“Vous desirez, Monsieur le Vicomte?”

“The young men may come in – but not the prisoners!” The last words were emphasized but so softly that none other than the

servant could hear them.

Whilst waiting for his orders to be carried out, Antoine de Valle allowed himself to dwell for a moment upon the thought of

tomorrow’s pleasures. In the morning he and his house guests would rendezvous at the hunting lodge in the heart of the great

forest of Compiègne. The dogs would be assembled and la chasse au sanglier would commence. Hopefully the animals would scent many of the wild boar grovelling in the thickets, root

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...