- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

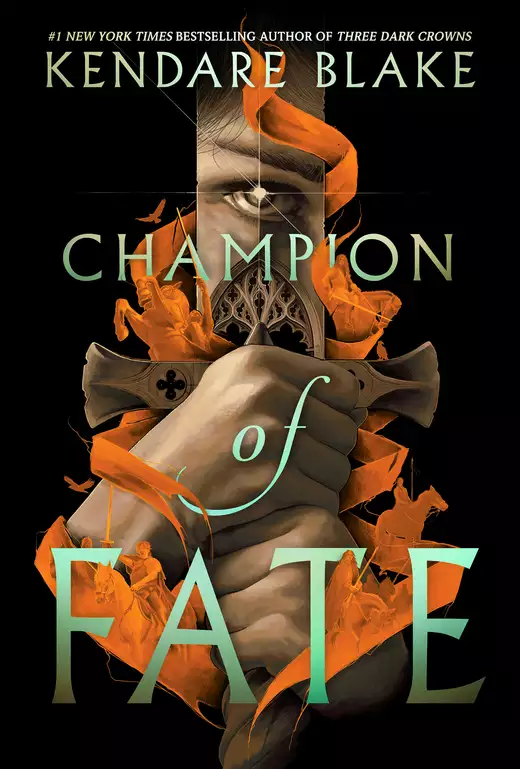

#1 New York Times bestselling author Kendare Blake is back with an epic duology starter that follows a young woman training to join a fabled order as she attempts to lead a hero to his critical first victory. A must-read for fans of Alexandra Bracken and Victoria Aveyard.

Aristene are an order of mythical female warriors. Though heroes might be immortalized in legends, it’s the Aristene who guide their paths to victory. They are the Heromakers.

Raised by the order after being orphaned, Reed grew up surrounded by her future sisters-in-arms and the incredible stories of their quests. She’s been counting the days until her initiation, and now one final test stands in her way: shepherding her first hero to glory on the battlefield. Succeed, and her place in the order is secured. Fail, and she’ll be cast out of the only home she’s ever known.

But Reed didn’t count on Hestion, her assigned hero, being both infuriating and intriguing. When their strategic alliance turns into something more, it forces Reed to question the cost of becoming an Aristene. As battle looms and fate hangs in the balance, Reed must make an impossible choice: her hero or her order.

Release date: September 19, 2023

Publisher: HarperCollins

Print pages: 480

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Champion of Fate

Kendare Blake

The rice balls in the basket looked wrong. It didn’t matter which way she stacked them or how carefully she and Mama had rolled and rerolled them into perfect shapes, stuffing each with sweetened paste made from the fruit that grew so plentifully around the new settlement. New fruit, tangy and soft, with a texture somewhere between bread and a root vegetable. Fruit that Reed had never seen before they came, not even in the large marketplace by the pier, where nearly anything could be found.

“Enough fussing with those balls,” Mama said. She had changed into her finest shift: soft linen dyed a dark crimson. “They will taste no better, and you’re likely to dent them. Pick up the basket. Let’s go.”

She sounded not cross but distracted, like she was giving the order to herself rather than to Reed. Today they went to see Orna, the Wise Woman. And Mama was no more excited about it than Reed was.

“She won’t even eat them if she knows I touched them,” Reed said. And to make the point she reached out a finger and touched one again.

“That isn’t true,” Mama said. But she used her thumbs to wipe spots of dirt from her daughter’s face and tugged her shoulders straight before they marched out of the lodge.

Reed didn’t like the new settlement. A new settlement for a new beginning, Papa said, but it was a jungle—hot and wild, the air too wet, and everything seemed to fight them: branches snapped back and hit her in the nose. Long grasses tangled around her slim, tan ankles to keep her from getting where she was going. Reed missed the port city where she’d grown up. Stone-paved roads and strong buildings, horses and ships and merchants who spoke many tongues.

“Why does it matter if Orna likes me or not?” Reed asked as she and her mother walked. “She can’t do anything to me.”

“It matters because it is unlucky. And because eventually it will make others . . . It will change the way others look at you.” Mama paused and reached down to smooth Reed’s long, dark hair. “Besides, she does like you. She was only irritable because of the seasickness and then the travel.”

Orna was on the last boat to arrive in the port from their home country. It was her arrival as much as their readiness that signaled it was time to depart for the settlement. Papa and Mama said she was a great mystic and a great healer who bent the ear of the gods. And she had hated little Reed the moment she set her old eyes on her.

“Mater Orna,” Mama said when they reached the door of the lodge. She used the honorary ‘mater’ to signify that they came to her as family.

Had they come for healing or blessings, Mama would have called her “Healer Orna” or “Wise Orna,” as the case allowed.

“Come in.”

They stepped through the door—which was not much of a door but a flap made from woven reeds and plant fibers, the same fibers that comprised the basket that Reed held—and found Orna seated on the floor, on silk pillows and a thick wool rug. Reed had heard Mama whisper that the pillows wouldn’t last long in the heat and wetness before they started to grow mold. Killy, the oldest daughter of the family who shared space with the Wise Woman, came forward to greet them from where she sat in the far corner, tending three toddlers. But when Orna saw them she simply said, “Oh, it’s you,” and went back to playing a solitary game with colored stones that Reed didn’t know how to play.

Mama nudged her, and Reed stepped forward to offer the basket of rice balls.

“For you, Mater Orna,” Reed said, and lowered her head. She and Mama waited in the silence. Long silence. Until Mama lost her temper.

“You don’t really mean to ignore her when she is right in front of you!”

“When who is right in front of me?” Orna asked.

Mama’s lips drew into a thin, grim line, an expression that Reed knew well. But Orna didn’t seem afraid, despite Mama’s great height and her strong arms, muscled from pulling fish from the sea and the river. The men of their people worked the earth. Papa knew how to make brick from mud and clay, how to sow seed and build lodges, but one day, Reed would work the water like her mother, strong enough to wade into the current and pull up the traps of crab and crayfish, strong enough to battle the fish who bit their lines. Even the flat ones, who hugged the silt and sand at the bottom.

“Reed is a good girl and a hard worker. I don’t care who you are; I won’t let you treat her like she is cursed!”

Reed’s chest warmed as Mama pulled her to her waist. No one was as fierce as Mama was. Not Papa. Not Auntie Lira. And certainly not mean Orna, who sat on legs like thin sticks and had cheeks like empty cloth.

“I never said she was cursed,” Orna said. “Nor did I say she was bad. I only said she was not ours.” At last, she looked at Reed, and Reed wished she hadn’t. The emptiness in that look made her feel even more invisible than before. “Not ours,” Orna said again. “Not mine and not yours, plain for anyone to see. So why get attached?”

“Orna,” Mama said, and tried once more. “Wise Orna, what does that mean?”

Orna’s eyes dropped to the basket of rice balls and for a moment Reed thought they had won, that she would take them and the unpleasant errand would be over.

“Take those out of here,” Orna said. “And let the girl have them. Give her something sweet. I do not think she will be with us for much longer.”

“What does that old hag know?”

Mama was irate as they walked through the settlement, past other lodges and the communal hearth, past the site of the future church—now just a square of large smooth stones.

“Mama,” Reed said, and tugged on her shift. They were passing the enclosure where they kept the goats and sheep and the many donkeys who had helped them carry their belongings through the wet, wooded country. Reed would have liked to stop and feed them a few rice balls, but Mama brushed her hand away and stalked on. She didn’t stop until they reached their lodge, and burst through the flap so quickly that it swung back and hit Reed in the face.

“Wise Orna,” Mama sneered to herself as she tore out of her good crimson dress and pulled on a white work dress yellowed with water stains. “More like Foolish Orna. Wicked Orna.” She wrapped her dark hair in brown fabric and secured it with a rough length of cord.

Mama looked at Reed, and Reed heard Orna’s words. She is not ours. Not mine, not yours.

“What a lot of nonsense.”

Reed peered into the basket of rice balls, and Mama’s foul mood eased: she cracked a rueful smile and laughed, which made Reed laugh, too.

“Go ahead,” she said. She reached in for a rice ball and took a big bite. “We can have a treat before going to the river. We deserve it, I’d say.”

Reed took two rice balls before going to change out of her good shift. By the river they dressed for the heat, with dark fabric over their shoulders to protect from the sun and white linens for easy wading into the shallows. River work should have been cooling, but where the water stagnated in the bend, it was sometimes as warm as a bath.

She walked with Mama out of the settlement to the river, eating a rice ball in tiny bites to make it last. She tucked the other one into a pouch around her neck, too high for the water to reach. She thought about offering it to Mama. But instead she decided to save it for Grey Anders, her favorite donkey.

That night, Reed lay by herself, tired after hours in the sun and mud, stretched out in the shadows while the rest of the lodge talked; gathered families trading the stories of the day. Papa sat on the only chair with two of the smaller children on his knees. He had his shirt off and laid across his lap. Mama snatched it from him and flicked him with it.

“Dress before dinner,” she said, smiling. “You’re starting to look like an Orillian.”

“And so I am,” he said, but he took the shirt back and pulled it over his head. “So are we all, now that Orillia is our home. In this new place we can leave our old things behind: no more leathers and woven cloaks. No more armor.” He placed the children on the floor and stood to take Mama’s face in his hands. “Or your jeweled pins. This place demands new ways.”

“And what about what we were? Does that have no value?” Mama didn’t often speak

of their lives before the port, but Reed had heard her say that in their home country, Papa was a rich man and a great soldier. Stories like that made Reed wonder why they ever left. But Papa spoke of the settlement as a great adventure.

Reed didn’t see the adventure in biting flies and digging for clams. She didn’t feel it in the hard ground under her sleeping mat. But she loved her father. Everything would be fine, as long as he and Mama said it would be, and Reed let her eyes drift shut.

The raiders came while the fires burned low and bowls from evening meals still rested in drowsy laps. They wove themselves into the settlement on silent feet, first one, then two, then many more, armed with short swords and spears and sharp knives strapped to their belts. They looped through the families in loose coils, like a lazy noose tossed around the head of an unwitting animal.

And then they pulled it taut.

Reed was asleep when the attack began, her head resting on her arm, thrown up toward the cooking fire as if waiting for someone to place a bowl of stew in her hand. She didn’t see her parents’ faces freeze when the raiders stepped into the light, their cheeks marked with a blue paste. She didn’t see her father stand and hold out his hands, nor hear him say, “We have nothing.” So she didn’t see the raider swing his sword and cut him down.

It was her mother’s scream that finally ripped her from sleep, and in the end, it was also what saved her. Mama charged their attacker and held his arms high, pushing him through the lodge like an ox. She meant to shove him right out through the door flap, but instead he pivoted and they slammed into the lodge wall, which had been built for peace from long sticks, plant fibers, and dried clay. The entire side of the lodge came down, right onto Reed, and she pulled her knees up tight as it knocked the breath from her lungs. Scrambling, she clawed at the ground, afraid she would be trampled and crushed into the dirt. All through the settlement came screams and wails and the sounds of running, stomping feet. The air smelled of smoke.

“Mama!” Reed pushed herself toward what she hoped was the way out. Rough bark and sharp grasses cut into her shoulders and legs. She had to help Mama. She would fight, and then they would run and hide by the river in the tall grass. When the sun came up they would find Papa and the others.

She pushed forward toward an orange-red glow, more light than the cook fire usually gave off. The lodge is burning, she thought, and then her mother’s body hit the ground in front of her.

Mama lay on the dirt floor, head rolling from side to side as blood ran from her chest to pool in the hollows of her collarbone. Reed froze.

“Mama!”

Mama looked at her. She saw her, huddled in the wreckage. “Stay,” she mouthed “I can’t,” Reed whispered. But she did as she was told. She remained still and quiet as fewer and fewer screams cut through the night, and the fire set to the lodge burned itself out. She stayed through the dark of night and into the morning, when the sun came up and showed her that her mother was dead.

The two riders had been on the road a long time and looked the worse for it; the light hemp of their shirts had pulled thin to holes, and they were spattered with mud to the knees. No one passing would have given them a second glance, except to note that they were women, and if they looked closer, that they were beautiful underneath all the dust and muck. But these were no ordinary riders. Nor were their horses, who they stopped to water at the stream, ordinary horses. They were Areion, sacred mounts of the order of the Aristene. They could have run for days without drinking, reaching speeds that would outpace the fastest of hunting cats. It was also said that the horses could speak, but only if one was worthy of their words.

Whether that was true not even the riders could say. They had raised the Areion from foals and never heard so much as a whisper. They had, however, caught many a hoof to the backside when the oats were late.

“Do you think we’ll reach an inn tonight, or will we camp again?” the taller of the two riders asked, leaning back in the saddle to stretch her neck.

“Pft. Court life has made you soft.” Her companion swung a leg over her horse’s withers and jumped to the ground. She shook dirt from her dark gold hair. “I haven’t been at any court for more than a decade”—she let the sand from her hair cascade from her fist: enough to make a small anthill—“and look at me now.”

The tall rider, called Aster, laughed. “Indeed, look at you. But I didn’t say that I preferred an inn to a field. It was only a question.”

Her companion, Veridian, smirked and knelt to drink beside her horse before dunking her entire head in the stream. She looked well, Aster had to admit. Not lonely. Nor bitter, or at least not any more bitter than usual. Aster had not seen her in fifteen years, when Veridian had turned her back on the Aristene order and been labeled an apostate. But time didn’t matter to them like it did to others. Its passing was of no more consequence than the passing of the water in the current, and Veridian looked the same as she always had: green-eyed and defiant.

“Perhaps I’ll go into those woods and try for a grouse,” Veridian said. “Roasted meat and crackling skin will ease the burden of another night sleeping on the grass.”

“I wasn’t complaining!” Aster laughed. But Veridian was already reaching into Everfall’s saddlebag for her crossbow and bolts. It would be nice to have a grouse for supper. The country they rode through was unfamiliar and sparsely inhabited. Some roads had been left unfinished, suddenly ending in a patch of grass or a line of trees, or growing gradually

thinner until they became little more than a game trail. But the birds in the region were fat, with a mild flavor from feeding on rice, both wild-grown and cultivated. The grouse had funny little tufted crowns and were depressingly easy to shoot, as if they were unused to being hunted. Aster had half a mind to snare a breeding pair and bring them back to the Citadel. She was considering how nice they would be, a little flock of tufted birds, all her own to be baked or fried, when she looked down and saw the stain of red in the water.

The horses’ heads came up.

“Do you smell that?” Aster asked.

Veridian tested the wind. “Ashes. Death.”

Aster’s hands gripped her reins until her knuckles shone white. “And glory.”

Reed shivered, fists clenching and releasing as she huddled beneath the wreckage of her family’s lodge. Panicked sweat had coated her and brought on a chill. She didn’t know how much longer she could go unnoticed. She hadn’t heard their language spoken in hours—only that of their attackers, a tongue that she didn’t recognize, even from all her years spent living in the port.

The attackers were not from here. They didn’t have the look of the Orillian people they had encountered. These men were tall and broad-shouldered. They painted their pale cheeks with blue mud. One, who she glimpsed by turning her body sideways and pushing slightly against the weight of the wall, had a long gold beard that ended in a braid. Now that the sun had come up, the beard seemed to bother him in the heat. He rubbed at it and scratched, and it dripped with water like he had wet it down.

Reed watched and listened, slowly moving beneath the wall. She had tested its weight in the night and found it not too heavy now that she was nearer to the edge. If no one found her under the debris, she might be able to escape when night came.

Except, she couldn’t leave Mama.

Her mother still lay where she fell, her face turned toward Reed in the wreckage.

Throughout the settlement, the raiders were collecting what spoils they could. They slaughtered goats to roast and led donkeys away on ropes. They picked up shards of broken pottery and plate; one man with ragged, shoulder-length hair picked up a woven mat and bent it back and forth. Then he snorted and dropped it, and Reed wanted to break his teeth with a stone.

She knew they would never find what they sought: Mama’s jeweled necklaces and gold hairpins were buried with Reed, somewhere under the fallen lodge. When the raiders were asleep, or after they had gone, Reed would dig until she found them, and then she would find her way back to the port. In the port, Reed had been entrusted with many errands, and many times she had traversed the city alone. But now there was no Papa to return to, no Mama to frighten a merchant who stated an unfair price. Maybe

she should just stay in the wreckage. Lay her head in the cool dirt and wait until she stopped breathing and joined her family in the beyond.

It might have come to that. Reed was only a child, eight autumns old. None of the gods in the world would have condemned her had she simply decided to give up. A kind god might have even helped her along. But it was not a kind god who found her.

At the raiders’ shouts of alarm, Reed jerked herself alert and shifted her position under the collapsed lodge to see, so the remains of the wall wobbled like a loose shell upon her back.

Two riders had come into the settlement. Two women, one on a bright red horse and another on a silvery gray. The raiders took up arms, and the one with the wet beard made his way to the front.

“The whole village annihilated,” said one of the women. She spoke in a common tongue, a language Reed knew well. “Is this really what you sensed?”

“And what you sensed,” said her companion. “Don’t deny it.” Despite being in a circle of armed men, the riders kept moving forward, their horses pushing the raiders and the bearded man closer and closer to Reed and her collapsed lodge. The riders’ clothes were filthy, but they didn’t carry themselves like beggars. The one with wild blond hair, who rode the red horse, cast her eyes over the body of Reed’s mother, prone and dead, her unarmed hands open. Reed’s small arms shook with anger. She is my mother, she wanted to shout. And she fought!

“There is no glory here,” the woman said quietly. “Only panic. No one put up a fight.” She nodded to Reed’s mother. “Except for that one.”

The bearded man leveled a spear at them. He asked what sounded like a question, and the blond woman answered him in his own language.

Reed watched. At any moment, she expected the men to strike, and the women to be murdered before her very eyes. But the blond woman talked, and the men listened. Reed noted the weapons the women carried: short swords on their backs and a longer one in a scabbard affixed to their saddles—she thought she glimpsed the edge of a shield beneath the saddle’s covering of leather. And then she realized that the gray horse was staring at her.

Reed didn’t know how the horse had seen her. And she certainly didn’t know why it should be so interested. But sure enough, the horse was staring.

“I know them,” the blond woman said to her brown-headed companion. “They’re Ithernan. Their lands are across the sea, to the northeast. They raid in the late summer and the fall for treasure and goods.”

“These people had little of either.”

The blond turned again to the bearded man and spoke a few words, then listened to his answer.

“It’s been an unsuccessful campaign,” she explained. “They make for home now

to try again to the west. This”—she gestured to the ruined settlement—“was something they just happened across. And it’s no business of ours.”

Reed started to breathe hard. The women were going to leave. They didn’t care that her family was dead. She looked at her mother, so fierce, murdered and cold on the ground, and screamed.

Reed sprang forth, legs aching after so long lying bent and still. She snatched a knife from the hip of the nearest raider, ready to drive it into their hearts. One of the men grabbed her by the neck and twisted the knife from her hand.

She struggled and snarled and tried to bite as she was hoisted up and her hands and feet bound. Over her grunts and shrieks of fury the bearded man spoke with the blond woman, and Reed twisted hard to look: the gray horse, and now her brown-haired rider, watched as she was carried off. Perhaps it was only a trick of her frightened eyes, but for a moment the woman didn’t look like a dirt-streaked wanderer. For just a moment, Reed caught a glimpse of something else: a warrior, glowing brightly and gilded in silver and soft white fabric.

“Don’t leave!” Reed shouted in the common tongue as the women turned their horses and rode away. But the man who carried her casually covered her mouth.

They found her mother’s jewels. It must have been small consolation to the raiders: a poor prize after all the trouble they had gone to sacking the settlement. But Mama’s small bag of finery had been more to her than money—it had been memories. The pieces she kept back when all the others were sold off to buy supplies.

“Those are my mother’s!” Reed shouted, and when a raider approached she kicked hard with her bound feet, kicking and kicking until he hauled her up painfully by her bound hands. He spoke words at her and squeezed her face hard. She jerked away and bit, digging her teeth into the meaty part between his thumb and forefinger.

“Ah!” he cried, and she grinned around his skin. Eventually he hit her in the side of the head hard enough to make her vision black in and out, and she slumped back into the dirt.

She came to later, when someone put a waterskin to her lips.

“I hate you,” she said after she drank, and the raider grunted like he understood. “I wish you were dead.” He grunted again. Then he cut the bindings on her feet and dragged her up by the arm.

He walked her past the charred wreck of the lodges, and as they passed a pile of bodies set to burn he made to cover her eyes. Reed shoved his hand away. They were her people. She had called many of them “auntie” and “uncle” even though they shared no blood. Now they lay stacked and covered in dark swarms of flies. On the top of the pile was old Orna. And even the sight of Orna, who she hated, made her sad.

The raider marched Reed out of the settlement to the riverbank. The donkeys were there, tied together and loaded with packs of goods all wrapped in leather and furs. In the water, slender wooden crafts bobbed, anchored to the bottom, and many more sat beached on the bank. They must have been able to travel quickly and quietly in crafts like those. No one must ever hear them coming.

The raider nudged Reed forward, through a patch of tall grass. Staked in the center, grazing, was a long-legged black colt.

“What is this horse doing here?” Reed asked. One horse. One horse, among the boats. And he was a beautiful horse, with a coat that shone and bright brown eyes and not a single white hair. She hadn’t seen his like since leaving the port.

The raiders began to load back into their boats. One came to lead Reed and the black colt on the bank as the boats launched down the river.

Good, Reed thought. The river ran nearly to the port. Perhaps someone at the mouth of the river would recognize her. Perhaps they would

rescue her and take her in.

But why would anyone do that? She was nothing now. Only another mouth to feed.

They hadn’t gone far before they had to stop for the night—that they had tried to depart at all with so little sun remaining spoke of their eagerness to be out of the jungle. Once again they drew their crafts up onto the bank, and those that did not fit were anchored to the bottom. The raider who led her tossed her half a skin of water and a few strips of dried fish before tying her to a tree. She intended to kick them away, but the moment she sniffed at the fish she began to devour it, savoring the salty chewiness and draining the waterskin in a few large gulps.

Reed wiped her mouth and looked around. The raiders were distracted, but they were everywhere, and there were not many moments when one or another pair of eyes were not on her. She stared right back. Their faces were dispassionate, not even curious. She didn’t understand why they had kept her.

Sand sprayed against her calf. There was no grass where they were tied, and the black colt was pawing crankily.

“I’d have saved you some fish, but you wouldn’t have eaten it,” Reed said. “Besides, you don’t look like you’re going to starve.”

The colt was well-fed to the point of being chubby. It was odd that they would bring him on such a journey when he was too young to ride. He must have been taken in another attack. Taken from his home like she was taken from hers.

“Here,” she whispered.

At the sound of her voice, the colt came closer to sniff at her. She put her hands to his cheeks and rested her forehead against his until he nudged her hard in the chest.

“Hey!” she said, but the colt continued to nudge, lips reaching for the pouch she had around her neck. The rice ball. She’d forgotten all about it.

She took it out of the pouch. It had dried up and been slightly crushed, but when she held it out the colt took it in one bite. For a few moments she felt almost well, almost happy, and as she watched him chew, a fierce wave of affection and protectiveness rushed over her.

“I will look after you,” she whispered. “I don’t know how. But I promise I will.”

Aster and Veridian hadn’t ridden far from the destroyed settlement. They hadn’t really been able to—Aster’s mount, the gray mare called Rabbit, had walked so slowly that her hooves left drag marks in the dirt.

“Eat your grouse,” Veridian said, watching Aster poke at her meal, golden and roasted on a spit. She took a large bite of her own, as if Aster was a child and needed to be shown how. “What’s the matter with you?”

“I can’t stop thinking about the girl,” she said. “Did you see the way she burst out from under that collapsed hut? The way she charged?”

Veridian grunted. “Of

course I did. I was right there.”

“She couldn’t have been more than ten.”

“Younger, I’d say,” Veridian mused around a mouthful of bird. “Maybe seven or eight.”

“So brave.”

“So angry. And who can blame her? She probably saw her whole family slaughtered. And she will join them soon enough.” Veridian threw a wing bone into the fire and watched it sizzle before tearing into thigh meat.

“What do you mean?” Aster asked.

“What did you think would happen to her?”

“I thought she would be traded off with the other goods. Or kept as labor or a future wife.”

“The Ithernan don’t marry outside their kind. And they don’t take slaves. If they did they wouldn’t have killed absolutely everyone.”

“The Ithernan,” Aster said. She’d never had occasion to deal with them. “You know them well.”

Veridian nodded. “One of their heroes, a long time ago, was mine. That blue they wear on their faces—it’s to draw the eye of their war god.”

“You know why they kept the girl, then?”

“To use as a sacrifice. They’ll cut her throat over the prow of their leader’s ship for a safe journey home.”

Aster frowned.

“They must’ve been glad to find her,” Veridian went on. “Normally they keep some of the prettier ones alive to choose from, but the attack must’ve gotten out of hand. Or they already had something to sacrifice. Another girl or a fast horse. They’re an interesting people—they believe the soul resides in the eyes. So eyes are sacred. With my green ones I was nearly worshipped as a god.” She went on talking, and eating, as Aster’s roasted bird slipped lower and lower, until the spit was almost resting on the ground.

“What?” Veridian groaned finally. “What is it?”

“I felt Her there today,” said Aster, and Veridian didn’t need to ask who she meant. Kleia Gloria, the goddess of glory. The only god an Aristene answered to.

“No, you didn’t.”

“Just because you have turned your back on Her, and on the Order—”

“That girl was eight years old,” Veridian said. “She’s a child.”

“You felt it, too.”

“I did not.”

But no matter what Veridian said or how she protested, she, too, was still an Aristene, down deep. And even if she truly hadn’t sensed anything back at the settlement, she would know that Aster would not be moved.

“Fine,” Veridian said, and threw away another picked-clean bone. “What do you want to do?” ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...