- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

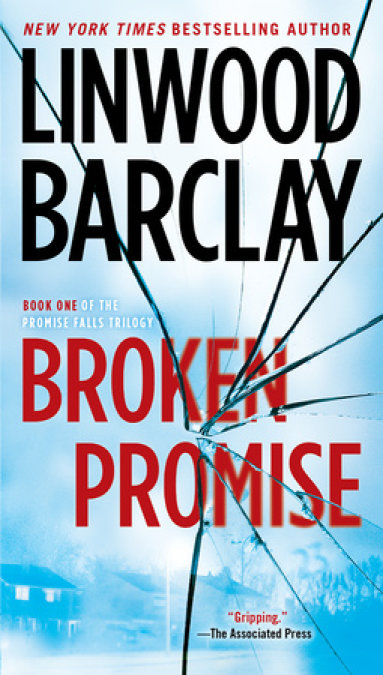

Broken Promise is the first book in the epic Promise Falls Trilogy from master of the thriller, Linwood Barclay.

When David Harwood is asked to look in on his cousin Marla, who is still traumatised after losing her baby, he thinks it will be some temporary relief from his dead-end life. But when he arrives, he's disturbed to find blood on Marla's front door. He's even more disturbed to find Marla looking after a baby, a baby she claims was delivered to her 'by an angel'.

Soon after, a woman's body is discovered, stabbed to death, with her own baby missing. It looks as if Marla has done something truly terrible.

But while the evidence seems overwhelming, David just can't believe that his cousin is a murderer. In which case, who did kill Rosemary Gaynor? Why did they then take her baby and give it to Marla? It's up to David to find out what really happened, but he soon discovers that the truth could be worse than he ever imagined . . .

Read by Quincy Dunn Baker and Brian O'Neill

Release date: July 28, 2015

Publisher: Berkley

Print pages: 464

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Broken Promise

Linwood Barclay

Copyright © 2015 Linwood Barclay

A couple of hours before all hell broke loose, I was in bed, awake since five, pondering the circumstances that had returned me, at the age of forty-one, to my childhood home.

It wasn’t that the room was exactly the same as when I’d moved out almost twenty years ago. The Ferrari poster no longer hung over the blue-striped wallpaper, and the kit I built of the starship Enterprise—hardened amberlike droplets of glue visible on the hull—no longer sat on the dresser. But it was the same dresser. And it was the same wallpaper. And this was the same single bed.

Sure, I’d spent the night in here a few times over the years, as a visitor. But to be back here as a resident? To be living here? With my parents, and my son, Ethan?

God, what a fucking state of affairs. How had it come to this?

It wasn’t that I didn’t know the answer to that question. It was complicated, but I knew.

The descent had begun five years ago, after my wife, Jan, passed away. A sad story, and not one worth rehashing here. After half a decade, there were things I’d had no choice but to put behind me. I’d grown into my role of single father. I was raising Ethan, nine years old now, on my own. I’m not saying that made me a hero. I’m just trying to explain how things unfolded.

Wanting a new start for Ethan and myself, I quit my job as a reporter for the Promise Falls Standard—not that hard a decision, considering the lack of interest by the paper’s management in actually covering anything approaching news—and accepted an editing position on the city desk at the Boston Globe. The money was better, and Boston had a lot to offer Ethan: the children’s museum, the aquarium, Faneuil Hall Marketplace, the Red Sox, the Bruins. If there was a better place for a boy and his dad, I couldn’t think where it might be. But . . .

There’s always a “but.”

But most of my duties as an editor took place in the evening, after reporters had handed in their stories. I could see Ethan off to school, sometimes even pop by and take him to lunch, since I didn’t have to be at the paper until three or four in the afternoon. But that meant most nights I did not have dinner with my son. I wasn’t there to make sure Ethan spent more time on his homework than video games. I wasn’t there to keep him from watching countless episodes of shows about backwoods duck hunters or airheaded wives of equally airheaded sports celebrities or whatever the latest celebration of American ignorance and/or wretched excess happened to be. But the really troubling thing was, I just wasn’t there. A lot of being a dad amounts to being around, being available. Not being at work.

Who was Ethan supposed to talk to if he had a crush on some girl—perhaps unlikely at nine, but you never knew—or needed advice on dealing with a bully, and it was eight o’clock at night? Was he supposed to ask Mrs. Tanaka? A nice woman, no doubt about it, who was happy to make money five nights a week looking after a young boy now that her husband had passed away. But Mrs. Tanaka wasn’t much help when it came to math questions. She didn’t feel like jumping up and down with Ethan when the Bruins scored in overtime. And it was pretty hard to persuade her to take up a controller and race a few laps around a virtual Grand Prix circuit in one of Ethan’s video games.

By the time I stepped wearily through the door—usually between eleven and midnight, and I never went out for drinks after the paper was put to bed because I knew Mrs. Tanaka wanted to return to her own apartment eventually—Ethan was usually asleep. I had to resist the temptation to wake him, ask how his day had gone, what he’d had for supper, whether he’d had any problems with his homework, what he’d watched on TV.

How often had I fallen into bed myself with an aching heart? Telling myself I was a bad father? That I’d made a stupid mistake leaving Promise Falls? Yes, the Globe was a better paper than the Standard, but any extra money I was making was more than offset by what was going into Mrs. Tanaka’s bank account, and a high monthly rent.

My parents offered to move to Boston to help out, but I wanted no part of that. My dad, Don, was in his early seventies now, and Arlene, my mother, was only a couple of years behind him. I was not going to uproot them, especially after a recent scare Dad put us all through. A minor heart attack. He was okay now, getting his strength back, taking his meds, but the man was not up to a move. Maybe one day a seniors’ residence in Promise Falls, when the house became too much for him and Mom to take care of, but moving to a big city a couple of hundred miles away—more than three hours if there was traffic—was not in the cards.

So when I heard the Standard was looking for a reporter, I swallowed my pride and made the call.

I felt like I’d eaten a bucket of Kentucky Fried Crow when I called the managing editor and said, “I’d like to come back.”

It was amazing there was actually a position. As newspaper revenues declined, the Standard, like most papers, was cutting back wherever it could. As staff left, they weren’t replaced. But the Standard was down to half a dozen people, a number that included reporters, editors, and photographers. (Most reporters were now “two-way,” meaning they could write stories and take pictures, although in reality, they were more like “four-way” or “six-way,” since they also filed for the online edition, did podcasts, tweeted—you name it, they did it. It wouldn’t be long before they did home delivery to the few subscribers who still wanted a print edition.) Two people had left in the same week to pursue nonjournalistic endeavors—one went to public relations, or “the dark side,” as I had once thought of it, and the other become a veterinarian’s assistant—so the paper could not provide its usual inadequate coverage of goings-on in Promise Falls. (Little wonder that many people had, for years, been referring to the paper as the Substandard.)

It would be a shitty place to go back to. I knew that. It wouldn’t be real journalism. It would be filling the space between the ads, at least, what ads there were. I’d be cranking out stories and rewriting press releases as quickly as I could type them.

But on the upside, I’d be back to working mostly days. I’d be able to spend more time with Ethan, and when I did have evening obligations, Ethan’s grandparents, who loved him beyond measure, could keep an eye on him.

The Standard’s managing editor offered me the job. I gave my notice to the Globe and my landlord and moved back to Promise Falls. I did move in with my parents, but that was to be a stopgap measure. My first job would be to find a house for Ethan and myself. All I could afford in Boston was a rented apartment, but back here, I’d be able to get us a proper home. Real estate prices were in free fall.

Then everything went to shit at one fifteen p.m. on Monday, my first day back at the Standard.

I’d returned from interviewing some folks who were petitioning for a crosswalk on a busy street before one of their kids got killed, when the publisher, Madeline Plimpton, came into the newsroom.

“I have an announcement,” she said, the words catching in her throat. “We won’t be publishing an edition tomorrow.”

That seemed odd. The next day was not a holiday.

“And we won’t be publishing the day after that,” Plimpton said. “It’s with a profound sense of sadness that I tell you the Standard is closing.”

She said some more things. About profitability, and the lack thereof. About the decline in advertising, and classifieds in particular. About a drop in market share, plummeting readership. About not being able to find a sustainable business model.

And a whole lot of other shit.

Some staff started to cry. A tear ran down Plimpton’s cheek, which, to give her the benefit of the doubt, was probably genuine.

I was not crying. I was too fucking angry. I had quit the goddamn Boston Globe. I’d walked away from a decent, well-paying job to come back here. As I went past the stunned managing editor, the man who’d hired me, on my way out of the newsroom, I said, “Good to know you’re in the loop.”

Out on the sidewalk, I got out my cell and called my former editor in Boston. Had the job been filled? Could I return?

“We’re not filling it, David,” he said. “I’m sorry.”

So now here I was, living with my parents.

No wife.

No job.

No prospects.

Loser.

It was seven. Time to get up, have a quick shower, wake up Ethan, and get him ready for school.

I opened the door to his room—it used to be a sewing room for Mom, but she’d cleared her stuff out when we moved in—and said, “Hey, pal. Time to get cracking.”

He was motionless under the covers, which obscured all of him but the topsy-turvy blond hair atop his head.

“Rise and shine!” I said.

He stirred, rolled over, pulled down the bedspread enough to see me. “I don’t feel good,” he whispered. “I don’t think I can go to school.”

I came up alongside the bed, leaned over, and put my hand to his forehead. “You don’t feel hot.”

“I think it’s my stomach,” he said.

“Like the other day?” My son nodded. “That turned out to be nothing,” I reminded him.

“I think this might be different.” Ethan let out a small moan.

“Get up and dressed and we’ll see how you are then.” This was becoming a pattern the last couple of weeks. Whatever ailment was troubling him, it certainly hadn’t been troubling him on weekends, when he could down four hot dogs in ten minutes, and had more energy than everyone else in this house combined. Ethan didn’t want to go to school, and so far I’d been unable to get him to tell me why.

My parents, who believed sleeping in was staying in bed past five thirty—I’d heard them getting up as I’d stared at that dark ceiling—were already in the kitchen when I made my entrance. They’d have both had breakfast by this time, and Dad, on his fourth coffee by now, was sitting at the kitchen table, still trying to figure out how to read the news on an iPad tablet, which Mom had bought for him after the Standard stopped showing up at their door every morning.

He was stabbing at the device with his index finger hard enough to knock it off its stand.

“For God’s sake, Don,” she said, “you’re not trying to poke its eye out. You just tap it lightly.”

“I hate this thing,” he said. “Everything’s jumping around all over the place.”

Seeing me, Mom adopted the excessively cheerful tone she always used when things were not going well. “Hello!” she said. “Sleep well?”

“Fine,” I lied.

“I just made a fresh pot,” she said. “Want a cup?”

“I can manage.”

“David, did I tell you about that girl at the checkout at the Walgreens? What was her name? It’ll come to me. Anyway, she’s cute as a button and she’s split up with her husband and—”

“Mom, please.”

She was always on the lookout, trying to find someone for me. It was time, she liked to say. Ethan needed a mother. I’d grieved long enough, she was forever reminding me.

I wasn’t grieving.

I’d had six dates in the last five years, with six different women. Slept with one. That was it. Losing Jan, and the circumstances around her death, had made me averse to commitment, and Mom should have understood that.

“I’m just saying,” she persisted, “that I think she’d be pretty receptive if you were to ask her out. Whatever her name is. Next time we’re in there together, I’ll point her out.”

Dad spoke up. “For God’s sake, Arlene, leave him alone. And come on. He’s got a kid and no job. That doesn’t exactly make him a great prospect.”

“Good to have you in my corner, Dad,” I said.

He made a face, went back to poking at his tablet. “I don’t know why the hell I can’t get an honest-to-God goddamn paper to my door. Surely there are still people who want to read an actual paper.”

“They’re all old,” Mom told him.

“Well, old people are entitled to the news,” he said.

I opened the fridge, rooted around until I’d found the yogurt Ethan liked, and a jar of strawberry jam. I set them on the counter and brought down a box of cereal from the cupboard.

“They can’t make money anymore,” Mom told him. “All the classifieds went to craigslist and Kijiji. Isn’t that right, David?”

I said, “Mmm.” I poured some Cheerios into a bowl for Ethan, who I hoped would be down shortly. I’d wait till he showed before pouring on milk and topping it with a dollop of strawberry yogurt. I dropped two slices of white Wonder bread, the only kind my parents had ever bought, into the toaster.

My mother said, “I just put on a fresh pot. Would you like a cup?”

Dad’s head came up.

I said, “You just asked me that.”

Dad said, “No, she didn’t.”

I looked at him. “Yes, she did, five seconds ago.”

“Then”—with real bite in his voice—“maybe you should answer her the first time so she doesn’t have to ask you twice.”

Before I could say anything, Mom laughed it off. “I’d forget my head if it wasn’t screwed on.”

“That’s not true,” Dad said. “I’m the one who lost his goddamn wallet. What a pain in the ass it was getting that all sorted out.”

Mom poured some coffee into a mug and handed it to me with a smile. “Thanks, Mom.” I leaned in and gave her a small kiss on her weathered cheek as Dad went back to stabbing at the tablet.

“I wanted to ask,” she said to me, “what you might have on for this morning.”

“Why? What’s up?”

“I mean, if you have some job interviews lined up, I don’t want to interfere with that at all or—”

“Mom, just tell me what it is you want.”

“I don’t want to impose,” she said. “It’s only if you have time.”

“For God’s sake, Mom, just spit it out.”

“Don’t talk to your mother that way,” Dad said.

“I’d do it myself, but if you were going out, I have some things I wanted to drop off for Marla.”

Marla Pickens. My cousin. Younger than me by a decade. Daughter of Mom’s sister, Agnes.

“Sure, I can do that.”

“I made up a chili, and I had so much left over, I froze some of it, and I know she really likes my chili, so I froze a few single servings in some Glad containers. And I picked her up a few other things. Some Stouffer’s frozen dinners. They won’t be as good as homemade, but still. I don’t think that girl is eating. It’s not for me to comment, but I don’t think Agnes is looking in on her often enough. And the thing is, I think it would be good for her to see you. Instead of us old people always dropping by. She’s always liked you.”

“Sure.”

“Ever since this business with the baby, she just hasn’t been right.”

“I know,” I said. “I’ll do it.” I opened the refrigerator. “You got any bottles of water I can put with Ethan’s lunch?”

Dad uttered an indignant, “Ha!” I knew where this was going. I should have known better than to have asked. “Biggest scam in the world, bottled water. What comes out of the tap is good enough for anybody. This town’s water is fine, and I should know. Only suckers pay for it. Next thing you know, they’ll find a way to make you pay for air. Remember when you didn’t have to pay for TV? You just had an antenna, watched for nothing. Now you have to pay for cable. That’s the way to make money. Find a way to make people pay for something they’re getting now for nothing.”

Mom, oblivious to my father’s rant, said, “I think Marla’s spending too much time alone, that she needs to get out, do things to take her mind off what happened, to—”

“I said I’d do it, Mom.”

“I was just saying,” she said, the first hint of an edge entering her voice, “that it would be good if we all made an effort where she’s concerned.”

Dad, not taking his eyes off the screen, said, “It’s been ten months, Arlene. She’s gotta move on.”

Mom sighed. “Of course, Don, like that’s something you just get over. Walk it off, that’s your solution to everything.”

“She’s gone a bit crackers, if you ask me.” He looked up. “Is there more coffee?”

“I just said I made a fresh pot. Now who’s the one who isn’t listening?” Then, like an afterthought, she said to me, “When you get there, remember to just identify yourself. She always finds that helpful.”

“I know, Mom.”

“You seemed to get your cereal down okay,” I said to Ethan once we were in the car. Ethan was running behind—dawdling deliberately, I figured, hoping I’d believe he really was sick—so I offered to drop him off at school instead of making him walk.

“I guess,” he said.

“There something going on?”

He looked out his window at the passing street scene. “Nope.”

“Everything okay with your teacher?”

“Yup.”

“Everything okay with your friends?”

“I don’t have any friends,” he said, still not looking my way.

I didn’t have a ready answer for that. “I know it takes time, moving to a new school. But aren’t there some of the kids still around that you knew before we went to Boston?”

“Most of them are in a different class,” Ethan said. Then, with a hint of accusation in his voice: “If I hadn’t moved to Boston I’d probably still be in the same class with them.” Now he looked at me. “Can we move back there?”

That was a surprise. He wanted to return to a situation where I was rarely home at night? Where he hardly ever saw his grandparents?

“No, I don’t see that happening.”

Silence. A few seconds went by, then: “When are we going to have our own house?”

“I’ve gotta find a job first, pal.”

“You got totally screwed over.”

I shot him a look. He caught my eye, probably wanting to see whether I was shocked.

“Don’t use that kind of language,” I said. “You start talking like that around me, then you’ll forget and do it front of Nana.” His grandmother and grandfather had always been Nana and Poppa to him.

“That’s what Poppa said. He told Nana that you got screwed over. When they stopped making the newspaper just after you got there.”

“Yeah, well, I guess I did. But I wasn’t the only one. Everybody was fired. The reporters, the pressmen, everyone. But I’m looking for something. Anything.”

If you looked up “shame” in the dictionary, surely one definition should be: having to discuss your employment situation with your nine-year-old.

“I guess I didn’t like being with Mrs. Tanaka every night,” Ethan said. “But when I went to school in Boston, nobody . . .”

“Nobody what?”

“Nothin’.” He was silent another few seconds, and then said, “You know that box of old things Poppa has in the basement?”

“The entire basement is full of old things.” I almost added, Especially when my dad is down there.

“That box, a shoe box? That has stuff in it that was his dad’s? My great-grandfather? Like medals and ribbons and old watches and stuff like that?”

“Okay, yeah, I know the box you mean. What about it?”

“You think Poppa checks that box every day?”

I pulled the car over to the curb half a block down from the school. “What on earth are you talking about?”

“Never mind,” he said. “It doesn’t matter.”

Ethan dragged himself out of the car without saying good-bye and headed in the direction of the school like a dead man walking.

Marla Pickens lived in a small, one-story house on Cherry Street. From what I knew, her parents—Aunt Agnes and her husband, Gill—owned the house and paid the mortgage on it, but Marla struggled to pay the property taxes and utilities with what money she brought in. Having spent a career in newspapers, and still having some regard for truth and accuracy, I didn’t have much regard for how Marla made her money these days. She’d been hired by some Web firm to write bogus online reviews. A renovation company seeking to rehabilitate and bolster its Internet reputation would engage the services of Surf-Rep, which had hundreds of freelancers who went online to write fictitious laudatory reviews.

Marla had once shown me one she’d written for a roofing company in Austin, Texas. “A tree hit our house and put a good-size hole in the roof. Marchelli Roofing came within the hour, fixed the roof, and reshingled it, and all for a very reasonable cost. I cannot recommend them highly enough.”

Marla had never been to Austin, did not know anyone at Marchelli Roofing, and had never, in her life, hired a contractor of any kind to do anything.

“Pretty good, huh?” she’d said. “It’s kind of like writing a really, really short story.”

I didn’t have the energy to get into it with her at the time.

I took the bypass to get from one side of town to the other, passing under the shadow of the Promise Falls water tower, a ten-story structure that looked like an alien mother ship on stilts.

When I got to Marla’s, I pulled into the driveway beside her faded red, rusting, mid-nineties Mustang. I opened the rear hatch of my Mazda 3 and grabbed two reusable grocery bags Mom had filled with frozen dinners. I felt a little embarrassed doing it, wondering whether Marla would be insulted that her aunt seemed to believe she was too helpless to make her own meals, but what the hell. If it made Mom happy . . .

Heading up the walk, I noticed weeds and grass coming up between the cracks in the stone.

I mounted the three steps to the door, switched all the bags to my left hand, and, as I rapped on it with my fist, noticed a smudge on the door frame.

The whole house needed painting or, failing that, a good power-washing, so the smudge, which was at shoulder height and looked like a handprint, wasn’t that out of place. But something about it caught my eye.

It looked like smeared blood. As if someone had swatted the world’s biggest mosquito there.

I touched it tentatively with my index finger and found it dry.

When Marla didn’t answer the door after ten seconds, I knocked again. Five seconds after that, I tried turning the knob.

Unlocked.

I swung it wide enough to step inside and called out, “Marla? It’s Cousin David!”

Nothing.

“Marla? Aunt Arlene wanted me to drop off a few things. Homemade chili, some other stuff. Where are you?”

I stepped into the L-shaped main room. The front half of the house was a cramped living room with a weathered couch, a couple of faded easy chairs, a flat-screen TV, and a coffee table supporting an open laptop in sleep mode that Marla had probably been using to say some nice things about a plumber in Poughkeepsie. The back part of the house, to the right, was the kitchen. Off to the left was a short hallway with a couple of bedrooms and a bathroom.

As I closed the door behind me, I noticed a fold-up baby stroller tucked behind it, in the closed position.

“What the hell?” I said under my breath.

I thought I heard something. Down the hall. A kind of . . . mewing? A gurgling sound?

A baby. It sounded like a baby. You might think, seeing a stroller by the door, that wouldn’t be all that shocking.

But here, at this time, you’d be wrong.

“Marla?”

I set the bags down on the floor and moved across the room. Started down the hall.

At the first door I stopped and peeked inside. This was probably supposed to be a bedroom, but Marla had turned it into a landfill site—disused furniture, empty cardboard boxes, rolls of carpet, old magazines, outdated stereo components. Marla appeared to be an aspiring hoarder.

I moved on to the next door, which was closed. I turned the knob and pushed. “Marla, you in here? You okay?”

The sound I’d heard earlier became louder.

It was, in fact, a baby. Nine months to a year old, I guessed. Not sure whether it was a boy or girl, although it was wrapped in a blue blanket.

What I’d heard were feeding noises. The baby was sucking contentedly on a rubber nipple, its tiny fingers attempting to grip the plastic feeding bottle.

Marla held the bottle in one hand, cradling the infant in her other arm. She was seated in a cushioned chair in the corner of the bedroom. On the bed, bags of diapers, baby clothes, a container of wipes.

“Marla?”

She studied my face and whispered, “I heard you call out, but I couldn’t come to the door. And I didn’t want to shout. I think Matthew’s nearly asleep.”

I stepped tentatively into the room. “Matthew?”

Marla smiled, nodded. “Isn’t he beautiful?”

Slowly, I said, “Yes. He is.” A pause, then: “Who’s Matthew, Marla?”

“What do you mean?” Marla said, cocking her head in puzzlement. “Matthew is Matthew.”

“What I mean . . . Who does Matthew belong to? Are you doing some babysitting for someone?”

Marla blinked. “Matthew belongs to me, David. Matthew’s my baby.”

I cleared a spot and sat on the edge of the bed, close to my cousin. “And when did Matthew arrive, Marla?”

“Ten months ago,” she said without hesitation. “On the twelfth of July.”

“But . . . I’ve been over here a few times in the last ten months, and this is the first chance I’ve had to meet him. So I guess I’m a little puzzled.”

“It’s hard . . . to explain,” Marla said. “An angel brought him to me.”

“I need a little more than that,” I said softly.

“That’s all I can say. It’s like a miracle.”

“Marla, your baby—”

“I don’t want to talk about that,” she whispered, turning her head away from me, studying the baby’s face.

I pressed on gently, as if I were slowly driving onto a rickety bridge I feared would give way beneath me. “Marla, what happened to you . . . and your baby . . . was a tragedy. We all felt so terrible for you.”

Ten months ago. It had been a sad time for everyone, but for Marla it had been devastating.

She lightly touched a finger to Matthew’s button nose. “You are so adorable,” she said.

“Marla, I need you to tell me whose baby this really is.” I hesitated. “And why there’s blood on your front door.”

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...