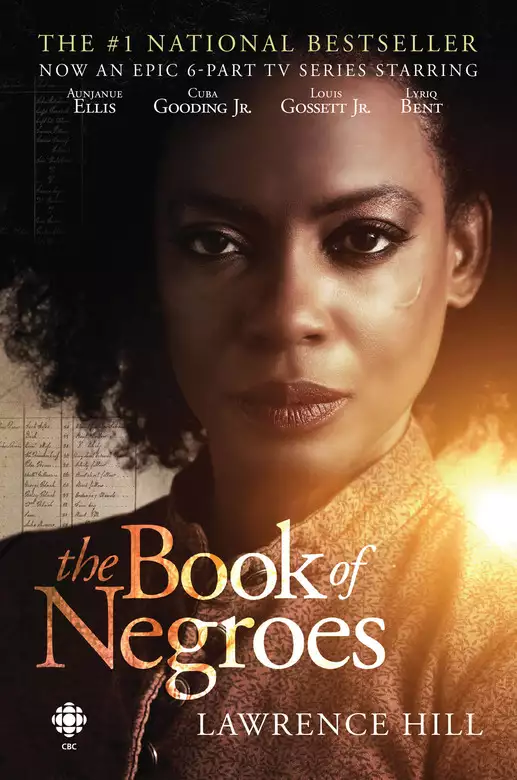

The Book Of Negroes

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Abducted as an 11-year-old child from her village in West Africa and forced to walk for months to the sea in a coffle - a string of slaves - Aminata Diallo is sent to live as a slave in South Carolina. But years later she forges her way to freedom, serving the British in the Revolutionary War and registering her name in the historic Book of Negroes. This book, an actual document, provides a short but immensely revealing record of freed loyalist slaves who requested permission to leave the United States for resettlement in Nova Scotia, only to find that the haven they sought was steeped in an oppression all its own.

Aminata's eventual return to Sierra Leone - passing ships carrying thousands of slaves bound for America - is an engrossing account of an obscure but important chapter in history that saw 1,200 former slaves embark on a harrowing back-to-Africa odyssey.

Lawrence Hill is a master at transforming the neglected corners of history into brilliant imaginings, as engaging and revealing as only the best historical fiction can be. A sweeping story that transports the listener from a tribal African village to a plantation in the Southern United States, from the teeming Halifax docks to the manor houses of London, The Book of Negroes introduces one of the strongest female characters in recent Canadian fiction, one who cuts a swath through a world hostile to her colour and her sex.

Release date: July 13, 2010

Publisher: Harper Perennial

Print pages: 584

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Book Of Negroes

Lawrence Hill

And now I am old

{LONDON, 1802}

Iseem to have trouble dying. By all rights, I should not have lived this long. But I still can smell trouble riding on any wind, just as surely as I could tell you whether it is a stew of chicken necks or pigs’ feet bubbling in the iron pot on the fire. And my ears still work just as good as a hound dog’s. People assume that just because you don’t stand as straight as a sapling, you’re deaf. Or that your mind is like pumpkin mush. The other day, when I was being led into a meeting with a bishop, one of the society ladies told another, “We must get this woman into Parliament soon. Who knows how much longer she’ll be with us?” Half bent though I was, I dug my fingers into her ribs. She let out a shriek and spun around to face me. “Careful,” I told her, “I may outlast you!”

There must be a reason why I have lived in all these lands, survived all those water crossings, while others fell from bullets or shut their eyes and simply willed their lives to end. In the earliest days, when I was free and knew nothing other, I used to sneak outside our walled compound, climb straight up the acacia tree while balancing Father’s Qur’an on my head, sit way out on a branch and wonder how I might one day unlock all the mysteries contained in the book. Feet swinging beneath me, I would put down the book—the only one I had ever seen in Bayo—and look out at the patchwork of mud walls and thatched coverings. People were always on the move. Women carrying water from the river, men working iron in the fires, boys returning triumphant from the forest with snared porcupines. It’s a lot of work, extracting meat from a porcupine, but if they had no other pressing chores, they would do it anyway, removing the quills, skinning the animal, slicing out the innards, practising with their sharp knives on the pathetic little carcass. In those days, I felt free and happy, and the very idea of safety never intruded on my thoughts.

I have escaped violent endings even as they have surrounded me. But I never had the privilege of holding onto my children, living with them, raising them the way my own parents raised me for ten or eleven years, until all of our lives were torn asunder. I never managed to keep my own children long, which explains why they are not here with me now, making my meals, adding straw to my bedding, bringing me a cape to hold off the cold, sitting with me by the fire with the knowledge that they emerged from my loins and that our shared moments had grown like corn stalks in damp soil. Others take care of me now. And that’s a fine thing. But it’s not the same as having one’s own flesh and blood to cradle one toward the grave. I long to hold my own children, and their children if they exist, and I miss them the way I’d miss limbs from my own body.

They have me exceedingly busy here in London. They say I am to meet King George. About me, I have a clutch of abolitionists—big-whiskered, wide-bellied, bald-headed men boycotting sugar but smelling of tobacco and burning candle after candle as they plot deep into the night. The abolitionists say they have brought me to England to help them change the course of history. Well. We shall see about that. But if I have lived this long, it must be for a reason.

Fa means father in my language. Ba means river. It also means mother. In my early childhood, my ba was like a river, flowing on and on and on with me through the days, and keeping me safe at night. Most of my lifetime has come and gone, but I still think of them as my parents, older and wiser than I, and still hear their voices, sometimes deep-chested, at other moments floating like musical notes. I imagine their hands steering me from trouble, guiding me around cooking fires and leading me to the mat in the cool shade of our home. I can still picture my father with a sharp stick over hard earth, scratching out Arabic in flowing lines and speaking of the

distant Timbuktu.

In private moments, when the abolitionists are not swirling about like tornadoes, seeking my presence in this deputation or my signature atop that petition, I wish my parents were still here to care for me. Isn’t that strange? Here I am, a broken-down old black woman who has crossed more water than I care to remember, and walked more leagues than a work horse, and the only things I dream of are the things I can’t have—children and grandchildren to love, and parents to care for me.

The other day, they took me into a London school and they had me talk to the children. One girl asked if it was true that I was the famous Meena Dee, the one mentioned in all the newspapers.

Her parents, she said, did not believe that I could have lived in so many places. I acknowledged that I was Meena Dee, but that she could call me Aminata Diallo if she wanted, which was my childhood name. We worked on my first name for a while. After three tries, she got it. Aminata. Four syllables. It’s really not that hard. Ah–ME–naw–tah, I told her. She said she wished I could meet her parents. And her grandparents. I replied that it amazed me that she still had grandparents in her life. Love them good, I told her, and love them big. Love them every day. She asked why I was so black. I asked why she was so white. She said she was born that way. Same here, I replied. I can see that you must have been quite pretty, even though you are so very dark, she said. You would be prettier if London ever got any sun, I replied. She asked what I ate. My grandfather says he bets you eat raw elephant. I told her I’d never actually taken a bite out of an elephant, but there had been times in my life when I was hungry enough to try. I chased three or four hundred of them, in my life, but never managed to get one to stop rampaging through villages and stand still long enough for me to take a good bite. She laughed and said she wanted to know what I really ate. I eat what you eat, I told her. Do you suppose I’m going to find an elephant walking about the streets of London? Sausages, eggs, mutton stew, bread, crocodiles, all those regular things. Crocodiles? she said. I told her I was just checking to see if she was listening. She said she was an excellent listener and wanted me to please tell her a ghost story.

Honey, I said, my life is a ghost story. Then tell it to me, she said.

As I told her, I am Aminata Diallo, daughter of Mamadu Diallo and Sira Kulibali, born in the village of Bayo, three moons by foot from the Grain Coast in West Africa. I am a Bamana. And a Fula. I am both, and will explain that later. I suspect that I was born in 1745, or close to it. And I am writing this account. All of it. Should I perish before

the task is done, I have instructed John Clarkson—one of the quieter abolitionists, but the only one I trust—to change nothing. The abolitionists here in London have already arranged for me to write a short paper, about ten pages, of why the trade in human beings is an abomination and must be stopped. I have done so, and the paper is available in the society offices.

I have a rich, dark skin. Some people have described it as blue black. My eyes are hard to read, and I like them so. Distrust, disdain, dislike—one doesn’t want to give public notice of such sentiments. Some say that I was once uncommonly beautiful, but I wouldn’t wish beauty on any woman who has not her own freedom, and who chooses not the hands that claim her.

Not much beauty remains now. Not the round, rising buttocks so uncommon in this land of English flatbacks. Not the thighs, thick and well packed, or the calves, rounded and firm like ripe apples. My breasts have fallen, where once they soared like proud birds. I have all but one of my teeth, and clean them every day. To me, a clean, white, full, glowing set of teeth is a beautiful thing indeed, and using the twig, vigorously, three or four times a day keeps them that way. I don’t know why it is, but the more fervent the abolitionist, it seems, the more foul the breath. Some men from my homeland eat the bitter kola nut so often that their teeth turn orange. But in England, the abolitionists do much worse, with coffee, tea and tobacco.

My hair has mostly fallen out now, and the remaining strands are grey, still curled, tight to my head, and I don’t fuss with them. The East India Company brings bright silk scarves to London, and I have willingly parted with a shilling here and there to buy them, always wearing one when I am brought out to adorn the abolitionist movement. Just above my right breast, the initials GO run together, in a tight, inch-wide circle. Alas, I am branded, and can do nothing to cleanse myself of the scar. I have carried this mark since the age of eleven, but only recently learned what the initials represent. At least they are hidden from public view. I am much happier about the lovely crescent moons sculpted into my cheeks. I have one fine, thin moon curving down each of my cheekbones, and have always loved the beauty marks, although the people of London do tend to stare.

I was tall for my age when I was kidnapped, but stopped growing after that and as a result stand at the unremarkable height of five feet, two inches. To tell the truth, I don’t quite hit that mark any longer. I keel to one side these days, and favour my right leg. My toenails are yellow and crusted and thick and most resistant to trimming. These days, my toes lift rather than settle

flat on the ground. No matter, as I have shoes, and I am not asked or required to run, or even to walk considerable distances.

By my bed, I like to keep my favourite objects. One is a blue glass pot of skin cream. Each night, I rub the cream over my ashen elbows and knees. After the life I have lived, the white gel seems like a magical indulgence. Rub me all the way in, it seems to say, and I will grant you and your wrinkles another day or two.

My hands are the only part of me that still do me proud and that hint at my former beauty. The hands are long and dark and smooth, despite everything, and the nails are nicely embedded, still round, still pink. I have wondrously beautiful hands. I like to put them on things. I like to feel the bark on trees, the hair on children’s heads, and before my time is up, I would like to place those hands on a good man’s body, if the occasion arises. But nothing—not a man’s body, or a sip of whisky, or a peppered goat stew from the old country—would give anything like the pleasure I would take from the sound of a baby breathing in my bed, a grandchild snoring against me. Sometimes, I wake in the morning with the splash of sunlight in my small room, and my one longing, other than to use the chamber pot and have a drink of tea with honey, is to lie back into the soft, bumpy bed with a child to hold. To listen to an infant’s voice rise and fall. To feel the magic of a little hand, not even fully aware of what it is doing, falling on my shoulder, my face.

These days, the men who want to end the slave trade are feeding me. They have given me sufficient clothes to ward off the London damp. I have a better bed than I’ve enjoyed since my earliest childhood, when my parents let me stuff as many soft grasses as I could gather under a woven mat. Not having to think about food, or shelter, or clothing is a rare thing indeed. What does a person do, when survival is not an issue? Well, there is the abolitionist cause, which takes time and fatigues me greatly. At times, I still panic when surrounded by big white men with a purpose. When they swell around me to ask questions, I remember the hot iron smoking above my breast.

Thankfully, the public visits are only so often and leave me time for reading, to which I am addicted like some are to drink or to tobacco. And they leave me time for writing. I have my life to tell, my own private ghost story, and what purpose would there be to this life I have lived, if I could not take this opportunity to relate it? My hand cramps after a while, and sometimes my back or neck aches when I have sat for too long at the table, but this writing business demands little. After the life I have lived, it goes down as easy as sausages and gravy.

Let me begin with a caveat to any and all who find these pages. Do not trust large bodies of water, and do not cross them. If you, dear reader, have an African hue and find yourself led toward water with vanishing shores, seize your freedom by any means necessary. And cultivate distrust of the colour pink. Pink is taken as the colour of innocence, the colour of childhood, but as it spills across the water in the light of the dying sun, do not fall into its pretty path. There, right underneath, lies a bottomless graveyard of children, mothers and men. I shudder to imagine all the Africans rocking in the deep. Every time I have sailed the seas, I have had the sense of gliding over the unburied.

Some people call the sunset a creation of extraordinary beauty, and proof of God’s existence. But what benevolent force would bewitch the human spirit by choosing pink to light the path of a slave vessel? Do not be fooled by that pretty colour, and do not submit to its beckoning.

Once I have met with the King and told my story, I desire to be interred right here, in the soil of London. Africa is my homeland. But I have weathered enough migrations for five lifetimes, thank you very much, and don’t care to be moved again.

Small hands were good

{Bayo, 1745}

No matter the time of life or the continent, the pungent, liberating smell of mint tea has always brought me back to my childhood in bayo. From the hands of traders who walked for many moons with bundles on their heads, magical things appeared in our village just as often as people vanished. Entire villages and towns were walled, and sentries were posted with poison-tipped spears to prevent the theft of men, but when trusted traders arrived, villagers of all ages came to admire the goods.

Papa was a jeweller, and one day, he gave up a gold necklace for a metal teapot with bulging sides and a long, narrow, curving spout. The trader said that the teapot had crossed the desert and would bring luck and longevity to any who drank from it.

In the middle of the next night, Papa stroked my shoulder while I lay in bed. He believed that a sleeping person has a vulnerable soul and deserves to be woken gently.

“Come have tea with your mama and me,” Papa said.

I scrambled out of bed, ran outside and climbed into my mother’s lap. Everybody else in the village was sleeping. The cocks were silent. The stars blinked like the eyes of a whole town of nervous men who knew of a terrible secret.

Mama and I watched as Papa used the thick, folded leaves from a banana plant to remove the teapot from three burning sticks. He lifted the lid that rose on mysterious hinges and used a whittled stick to scrape honey from a comb into the bubbling tea.

“What are you doing?” I whispered.

“Sweetening the tea,” he said.

I brought my nose near. Fresh mint leaves had been stuffed into the pot, and the fragrance seemed to speak of life in distant places.

“Hmm,” I said, breathing it in.

“If you close your eyes,” Papa said, “you can smell all the way to Timbuktu.”

With a hand on my shoulder, my mother also inhaled and sighed.

I asked Papa where, exactly, was Timbuktu? Far away, he said. Had he been there? Yes, he said, he had. It was located on the mighty Joliba River, and he had once travelled there to pray, to learn and to cultivate his mind, which every believer should do. This made me want to cultivate my mind too. About half of the people of Bayo were Muslims, but Papa was the only one who had a copy of the Qur’an, and who knew how to read and write. I asked how far it was across the Joliba. Was it like crossing the streams near Bayo? No, he said, it was ten times the distance a man could throw a stone. I couldn’t imagine such a river.

When the tea was strong and sweet with the gift of the bees, Papa lifted the steaming pot to the full height of his raised arm, tipped the spout, and poured the boiling liquid into a small calabash for me, another for Mama and a third for himself. He didn’t spill a drop. He set the teapot back on the embers, and warned me to let the drink cool.

I cupped my palms around the warm calabash and said, “Tell me again, Papa, about how you and Mama met.”

I loved to hear the story about how they had never been meant to set

eyes on each other, Mama being a Bamana and Papa a Fula. I loved how their story defied the impossible. They were never supposed to meet, let alone come together and start a family.

“A lucky thing for strange times,” Papa said, “or you would not have been born.”

Just one rain season before my birth, Papa had set out with other Fulbe men from Bayo. They had walked for five suns to trade their shea butter for salt in a distant market. On the way home, they gave a little pouch of salt to the chief of a friendly Bamana village. The chief invited them into the village to eat and rest and spend the night. While eating, Papa noticed Mama passing by. She was balancing on her head a tray of three yams and a calabash of goat’s milk. Papa drank in her smooth walking gait, level head, lifted chin, the arch of her back, her long, strong legs and the heels of her feet, dyed red.

“She seemed serious and dependable, but not to be trifled with,” Papa said. “I knew in an instant that she would become my wife.”

Mama sipped her tea and laughed. “I was busy,” she said, “and your father was in my way. I was going to help a woman who was ready to have her baby.”

Mama had no children yet, but had already brought many babies into the world. Papa found Mama’s father, and made inquiries. He learned that Mama’s first husband had disappeared many moons earlier, shortly after they had married. People assumed that he was either dead or kidnapped. Papa’s wife—to whom he had been betrothed before he or she were even born—had recently died of fever.

Mama was brought to meet Papa. This interrupted the catching of the baby, and she told him so. Papa smiled, and noted the muscles at the back of her legs as she turned to go back to her work. Negotiations continued about how to compensate Mama’s father for the loss of a daughter. They settled on six goats, seven bars of iron, ten copper manillas and four hundred strung cowrie shells.

These were troubled times, and without all the turmoil, the marriage between a Fula and a Bamana would not have been permitted. People were disappearing, and villagers were so concerned about falling into the hands of kidnappers that new alliances were forming among neighbouring villages. Hunters and fishermen travelled in groups. Men spent days at a time building walls around towns and villages.

Papa brought Mama to his village of Bayo. He made jewellery with fine threads of gold and silver and travelled to bring his goods to markets and to pray in mosques. He sometimes returned with the Qur’an or with other writings, in Arabic. He claimed that it was not the place of a girl to learn to read or write, but relented when he saw me attempting to draw words in Arabic with a stick in the sand. So, in the privacy of our home, with nobody

but my mother as a witness, I was shown how to use a reed, dyed water and parchment. I learned to write phrases in Arabic, such as Allaahu Akbar (God is great) and Laa ilaaha illa-Lah (There is none worthy of worship except God).

Mama spoke her native Bamanankan, a language she always used when the two of us were alone together, but she also had picked up much Fulfulde and learned some prayers from Papa. Sometimes, while I watched, a gaggle of Fulbe women would bump elbows and tease one another as Mama bent over with a sharpened stick and scratched Al-hamdulillah (Praise be to God) in the earth, to prove to the village women that she had learned some Arabic prayers. Nearby, the women pounded millet, using heavy wooden pestles that were long like human legs and smooth like baby skin and hard like stone. When they flung their pestles against the mortars full of millet, it sounded like drummers beating out a song. Once in a while, they paused to sip water and examine their calloused palms, while Mama repeated the words she had learned from Papa.

By the time I came along, Mama was respected in the village. Like the other women, she planted maize and millet, and collected shea nuts. She dried the nuts in a wood-fired kiln and pounded them with her pestle to extract the oil. Mama kept most of the oil, but set aside some of it for bringing babies into the world. Mama was always wanted when a woman was ready to bring a child to light. Once she even helped a donkey stalled in labour. She had a peaceful smile when she was happy and felt safe, a smile that I have thought of every day since I was ripped away from her.

When my time came, I refused to enter the world. Papa said that I was punishing my mother for conceiving me. Finally, Mama summoned Papa.

“Speak to your child,” she told him, “for I am growing weary.” Papa placed his hand flat on Mama’s belly. He brought his mouth close to her navel, which bulged like an unbloomed tulip. “Son,” Papa said.

“You don’t know that we have a son in here,” Mama said.

“If you keep taking so long, we just may end up with a goat,” Papa said. “But you have asked me to speak, and I am thinking of a son. So, dear Son, come out of there now. You have been living the good life, sleeping and clinging to your mother. Come now, or I shall beat you.”

Papa claimed that I answered him from the womb.

“I am not a boy,” he told me I said, “and before I come out, we must talk.”

“Then talk.”

“To come out right now, I require hot corn cakes, a calabash of fresh milk, and that fine drink the unbelievers tap from the tree—”

“No palm wine,” my father cut in. “Not for one who fears Allah. But I can bring cakes when you have teeth, and Mama will supply the milk. And if you are good, one day I shall give you the bitter kola nut. Allah doesn’t mind the kola.”

Out I came, sliding from my mother like an otter from a riverbank.

As an infant, I travelled on my mother’s back. She slid me around to her breast when I cried for food, and passed me among villagers, but usually I was swathed in red and orange cloth and rode low down on her back when she walked to market, pounded millet into flour, fetched water from the spring and tended to births. I remember wondering, within a year or two of taking my first steps, why only men sat to drink tea and converse, and why women were always busy. I reasoned that men were weak and needed rest.

As soon as I could walk, I made myself useful. I collected shea nuts, and scrambled up trees to fetch mangoes and avocadoes, oranges and other fruits. I was made to hold other women’s babies, and to keep them content. There was nothing wrong with a girl as young as three or four rain seasons holding and caring for a baby while the mother did other work. Once, however, Fanta, the youngest wife of the village chief, slapped me when she found me attempting to make a baby suckle me.

By my eighth rain season, I had heard stories of men in other villages being stolen by invading warriors or even sold by their own people, but never did it seem that this could happen to me. After all, I was a freeborn Muslim. I knew some of the Arabic prayers, and even had the proud crescent moon carved high into each of my cheeks. The crescent moons were to make me beautiful, but they also identified me as a believer among my Fulbe villagers. There were three captives—all unbelievers—in our village, but even children knew that no Muslim was allowed to hold another Muslim in captivity. I believed that I would be safe.

My father said it was so, when I came to him with all the stories that the village children chanted: somebody, some night, was sure to snatch me from my bed. Some said it would be our people, the Fulbe. Others warned about my mother’s people, the Bamana. Still others talked of the mysterious toubabu, the white men, whom none of us had ever seen. Put those silly children out of your mind, Papa said. Stay close to your Mama and me, don’t go out wandering alone, and you will be fine. Mama wasn’t quite

as confident. She tried to warn him about travelling such long distances, to sell his jewellery and to pray in mosques. Once or twice, at night when I was supposed to be sleeping, I heard them arguing. Don’t go travelling so far, Mama said, It’s not safe. And Papa said, We travel in groups, with arrows and clubs, and what man would test his strength against me? Mama: I have heard that before.

Mama took me along when women were at their biggest, ballooning from within. I watched her quick hands loosen umbilical cords from babies’ necks. I saw her reach inside a woman, with the other hand firm and pushing outside the womb, to turn the baby around. I saw her rub oil into her hands and massage a woman’s private parts to relax her skin and prevent it from tearing. Mama said that some women had their womanly parts cut up and put back together very badly. I asked what she meant. She smashed an old ceramic pot of no value, pushed apart the pieces, discarded one or two, and then had me try to reassemble it. I managed to stick some pieces together, but they were jagged, and stuck out and didn’t quite fit any longer.

“Like that,” Mama said.

“What happens to a woman like that?”

“She might survive. Or she might bleed too much and die. Or she might die when she tries to push out her first baby.”

Over time, I watched how Mama helped women have their babies. She had a series of goatskin pouches, and I learned the names of all her crushed leaves, dried bark and herbs. As a game, to test myself, I tried to anticipate when Mama would encourage a woman to ride out all the shaking in her belly. From the way the woman moved, breathed and smelled, and from the way she let out a guttural, animal-like sound when she was at the height of her convulsing, I tried to guess when she would start to push. Mama usually brought along an antelope bladder full of a drink made from the bitter tamarind fruit and honey. When the woman cried out in thirst, I would pour a little into a calabash and pass it along, proud of my service, proud to be dependable.

After Mama caught a baby in another village, the mother’s family would give her soap and oils and meats, and Mama would eat with the family and praise me for being her little helper. I cut through my first rope of life at the age of seven rains, holding the knife fast and sawing on and on until I made it all the way through the resistant cord. One rain season later, I was catching babies as they slid out. Later still, my mother taught me how to reach inside a woman—after coating my hand with warm oil—and to touch in the right spot to tell if the door was suitably wide. I became adept at that, and Mama said it was good to have me along because my hands were so small.

Mama began to speak to me about how my body would change. I would soon start bleeding, she said, and around that time some women would work with her to perform a little ritual on me. I wanted to know more about that ritual. All girls have it done when they are ready to become women, she said. When I pressed for details, Mama said that part of my womanhood was to be cut off so that I would be considered clean and pure and ready for marriage

I was none too impressed by this, and informed her that I was in no hurry to marry and would be declining the treatment. Mama said that no person could be taken seriously without being married, and that in due time, she and Papa would tell me about their plans for me. I told her that I remembered what she had said earlier, about some people having their womanly parts torn apart and put back together improperly. She carried on with an implacable confidence that left me worried. “Did they do this to you?” I asked her.

“Of course,” she said, “or your father would never have married me.”

“Did it hurt?”

“More than childbirth, but it didn’t last long. It is just a little correction.”

“But I have done nothing wrong, so I am in no need of correction,” I said. Mama simply laughed, so I tried another approach. “Some of the girls told me that Salima in the next village died last year, when they were doing that thing to her.”

“Who told you that?”

“Never mind,” I said, employing one of her expressions. “But is it true?”

“The woman who worked on Salima was a fool. She was untrained, and she tried to do too much. I’ll take care of you when the time comes.”

We let the matter drop, and never had the chance to discuss it again.

In our village, there was a strong, gentle man named Fomba. He was a woloso, which in my mother’s language meant captive of the second generation. Since his birth, he had belonged to our village chief. Fomba wasn’t a freeborn Muslim, and never learned the proper prayers in Arabic, but sometimes he kneeled down with Papa and the believers, facing in the direction of the rising sun.

Fomba had muscled arms and thick legs. He was the best shot in the village. Once, I saw him take sixty paces back from a lizard on a tree, draw back his bow and release the arrow. It shot right through the lizard’s abdomen, pinning it to the bark.

The village chief let Fomba go hunting every day, but released him from the tasks of planting and harvesting millet because he never seemed able to grasp all the rules or techniques, or to know how to work with a team of men. The children loved to follow Fomba about the village, watching him. He had a strange way of holding his head, tilting it way off to the side. Sometimes we gave him a platter of empty calabashes and asked him to balance it on his head, just for the pleasure of watching the whole thing slide off and crash to the ground. Fomba let us do that to him time and again.

We teased Fomba mercilessly, but he never seemed to mind us children. He would smile, and put up with rude taunts that would have gotten us beaten by any other adult in Bayo.

On some days, we would hide behind a wall and spy on Fomba while he played with the ashes of a fire. This was one of his favourite activities. Long after the women had done their cooking and we had eaten millet balls and sauce and finished using soap from the ashes of banana leaves to clean the pots, Fomba would bring a stick to the fire and poke around in the ashes. One day he trapped five chickens in a fishing net. He brought them out one by one, wrang their necks, plucked and cleaned and gutted them. Then he drove a sharp iron rod through their bodies and set them over a fire to roast.

Fanta, the youngest wife of the village chief, came running from the millet-pounding circle and smacked him about the head.

It seemed strange to me that he didn’t try to protect himself. “The children need meat,” was all he said.

Fanta scoffed. “They don’t need meat until they can work,” she said. “Stupid woloso. You have just wasted five chickens.”

Under Fanta’s gaze, Fomba kept roasting the chickens, and then pulled them out of the fire, cut them up and handed the pieces to us. I took a leg, burning hot, and grabbed a leaf to protect my fingers. Warm juice ran down my chin as I sucked the brown flesh and crunched the bone to suck out the marrow. I heard that night that Fanta told her husband to beat the man, but he refused.

One day, Fomba was sent to kill a goat that had suddenly started biting children and acting like its mind had departed. Fomba caught the goat, made it sit, put his arm around it, patted its head to calm it down. Then, he drew a knife from his loincloth and sliced the neck where the artery was thick. The goat lay still in Fomba’s arms, staring like a baby at him as it bled ferociously, weakened, and died. Fomba, however, hadn’t positioned himself cleverly, and blood ran all over him. He stood in the middle of the village compound, ringed by mud homes, and called out for hot water. The women were pounding millet, and Fanta told the others to ignore him. But Mama had a soft spot for Fomba. I had heard her once, at night, telling Papa that Fanta mistreated the woloso. I wasn’t surprised when Mama took leave of the millet pounding, grabbed a prized metal bucket, poured in several calabashes of hot water and carried it over to Fomba, who lugged it into the bathing enclosure.

I thought the bucket was magical. One day, I snuck into Fanta’s round, thatched home. I found the bucket and brought it into the better light by the door. It was made of smooth, rounded metal, and reflected sunlight. The metal was thin, but I was unable to bend it. I turned it upside down and beat it with the heels of my palms. It swallowed sound. The metal had no character, no personality, and was

useless for making music. It was not at all like goatskin pulled taut across the head of a drum. The bucket was said to have come from the toubabu. I wondered what sort of person would invent such a thing.

I tried lifting and swinging it by the looping metal handle. At that moment, Fanta came upon me, ripped the bucket from my hand, hung it from a peg in the wall, and popped me on the side of my head.

“You came into my house with no permission?”

Slap.

“No, I was just …”

“It’s not for you to touch.”

Slap.

“You can’t beat me like this. I’ll tell my father.”

Slap.

“I’ll beat you all I want. And he’ll beat you again when he hears that you were in my home.”

Fanta, who had been planting millet in the boiling sun, had beads of sweat on her lip. I saw that she had better things to do than to stand there hitting me all day. I ducked and ran out of her home, knowing she would not follow.

Papa was one of the biggest men in bayo. It was said that he could outwrestle any man in our village. One day, he crouched low to the ground and called for me. Up I climbed onto his back, all the way to his shoulders. There I sat, higher than the tallest villager, my legs curled around his neck and my hands in his. He took me outside the walled village, me riding high up like that.

“Since you are so strong and can make such beautiful jewellery,” I said, “why don’t you take a second wife? Our chief has four wives!”

He laughed. “I cannot afford four wives, my little one. And why do I need four wives, when your mother gives me all the trouble I can manage? The Qur’an says that a man must treat all his wives equally, if he is to have more than one. But how could I treat anyone as equally as your mother?”

“Mama is beautiful,” I said.

“Mama is strong,” he said. “Beauty comes and goes. Strength, you keep forever.”

“What about the old people?”

“They are the strongest of all, for they have lived longer than all of us, and they have wisdom,” he said, tapping his temple. We stopped at the edge of a forest.

“Does Aminata go wandering off alone this far?” he asked. “Never,” I said.

“Which way is the mighty Joliba, river of many canoes?”

“That way,” I said, pointing north. “How far?”

“Four suns, by foot,” I said.

“Would you like to see the town of Segu one day?” he said. “Segu on the Joliba?” I asked. “Yes. If I get to ride on your shoulders.”

“When you are old enough to walk for four suns, I will take you for a visit.”

“And I will travel, and cultivate my mind,” I said. “We will not speak of that,” he said. “Your task is to become a woman.”

Papa had already shown me how to scratch out a few prayers in Arabic. Surely he would show me more, in good time.

“Mama’s village is over there, five suns away,” I said, pointing east.

“Since you are so clever, pretend I am blind and show me the way home.”

“Are we cultivating my mind now?”

He chuckled. “Show me the way home, Aminata.”

“Go that way, past the baobab tree.”

We made it that far. “Turn this way. Take this path. Watch out. Mama and I saw three white scorpions on this path yesterday.” “Good girl. Now what?”

“Ahead, we enter our village. The walls are thick and as high as two men. We come in this way. Say hello to the sentry.”

Papa laughed and saluted the sentry. We approached the chief’s rectangular house, and passed the four round homes, one for each wife.

“Let me know when we pass Fanta’s house.”

“Why, Papa?”

“Perhaps we should stop in and drum your favourite bucket.” I laughed and slapped his shoulder playfully and told him, in a whisper, that I did not like that woman. “You must learn respect,” Papa said. “But I do not respect her,” I said.

Papa paused for a moment, and patted my leg. “Then you must learn to hide your disrespect.”

Papa walked on, and soon, two women came upon us.

“Mamadu Diallo,” one called out to Papa, “that is not the way to educate your daughter. She has legs for walking.”

My father’s real name was Muhammad. But every Muslim man in the village was thus named, so he went by Mamadu to distinguish himself.

“Aminata and I, we were having a little chat,” Papa told the women, “and I needed her ears close to my mouth.”

The woman laughed. “You spoil her.”

“Not a chance. I am training her to carry me the same way, when I am old.”

The women bent over, slapping their thighs in laughter. We said goodbye, and I continued to direct Papa past the walled enclosure for bathing, past the shaded bench for palavering and past the round huts for storing millet and rice. And then Papa and I came upon Fanta, who was pulling

Fomba by the ear.

“Stupid man,” she said.

“Hello, Fourth Wife of Chief,” Papa said.

“Mamadu Diallo,” she said.

“No salutations for my little girl today?” Papa said.

She grimaced and said, “Aminata Diallo.”

“And why are you dragging poor Fomba thus?” Papa said. She still had the man by the ear.

“He led an ass to the well, and it fell in,” she said. “Put down that spoiled girl, Mamadu Diallo, and help us fetch out the ass before it soils our drinking water.”

“If you let go of Fomba, who needs his ear, I shall help you with the ass.”

Papa let me down from his shoulders. Fomba and I watched Papa and some other men tie vines around a village boy and send him deep into the well. The boy in the well wrapped more vines around the ass, and was hoisted out. Then Papa and the men hauled out the ass. The animal seemed undisturbed, and on the whole less bruised than Fomba’s ear.

I wanted my papa to teach me how to tie vines around the belly of a donkey. Maybe he would teach me everything he knew. It wouldn’t hurt anybody if I learned to read and write. Perhaps, one day, I would be the only woman, and one of the only people in my entire village, to be able to read the Qur’an and to write in the gorgeous, flowing Arabic script.

One day, Mama and I were called from our millet pounding to attend a birth in Kinta, four villages away in the direction of the setting sun. The men were weeding the millet fields, but Fomba was told to fetch his bow and a quiver of poisoned arrows and to walk with us for our protection. When we arrived in Kinta, Fomba was given a place to drink tea and rest, and we went to work. The birth stretched from the morning into the evening, and by the time Mama had caught the baby and swaddled him and brought him to his mother’s nipple, fatigue had gripped our bones. We took some millet cakes in hot gumbo sauce, which I loved. Before we left, the village women warned us to stay off the main trail leading from the village, because strange men—unknown in any neighbouring villages—had been spotted lately. The villagers asked if we would like to stay the night with them. My mother refused, because another mother in Bayo was expecting her baby at any time. As we prepared to leave, the villagers gave us a skin of water and three live chickens bound by the feet, along with a special

gift of thanks—a metal pail, like the big washing bucket Fomba used the day he killed the goat.

Fomba couldn’t carry a thing on his head because his neck was always bent to the left, so Mama told him to carry the pail, into which the chickens were stuffed. Fomba seemed proud of his acquisition, but Mama warned him that he would have to surrender it when we returned to the village. He nodded happily and set out ahead of us.

“When we get home, can I have the pail?” I asked.

“The pail belongs to the village. We will give it to the chief.”

“But then Fanta will get it.”

Mama held her breath. I could tell that she didn’t like Fanta, either, but she watched her words.

We walked under a full moon that blazed in the night sky and lit our path. When we were almost home, three hares dashed in front of us, one right after the other, disappearing into the woods. Fomba set down his bucket, lifted a throwing stone from a flap at the hip of his loincloth and cocked his arm. He seemed to know that the hares would scurry back across the path. When they reappeared, Fomba pegged the slowest hare in the head. He stooped to pick it up, but Mama held him back. The hare was thick around the middle. Mama ran her finger along the body. The rabbit had been pregnant. It would make a fine stew, Mama told Fomba, but next time he saw rabbits streaking across the trail, he should sharpen his aim and take the fastest one—not the female lugging babies in her belly. Fomba nodded and draped his swollen prey over his shoulder. He stood up and resumed walking, but suddenly bent his neck even further to the side and listened.

There was more rustling in the bushes. I looked for another sign of the hares. Nothing. We walked more quickly. Mama reached for my hand.

“If strangers come upon us, Aminata—” she began, but got no further.

From behind a grove of trees stepped four men with massive arms and powerful legs. In the moonlight, ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...