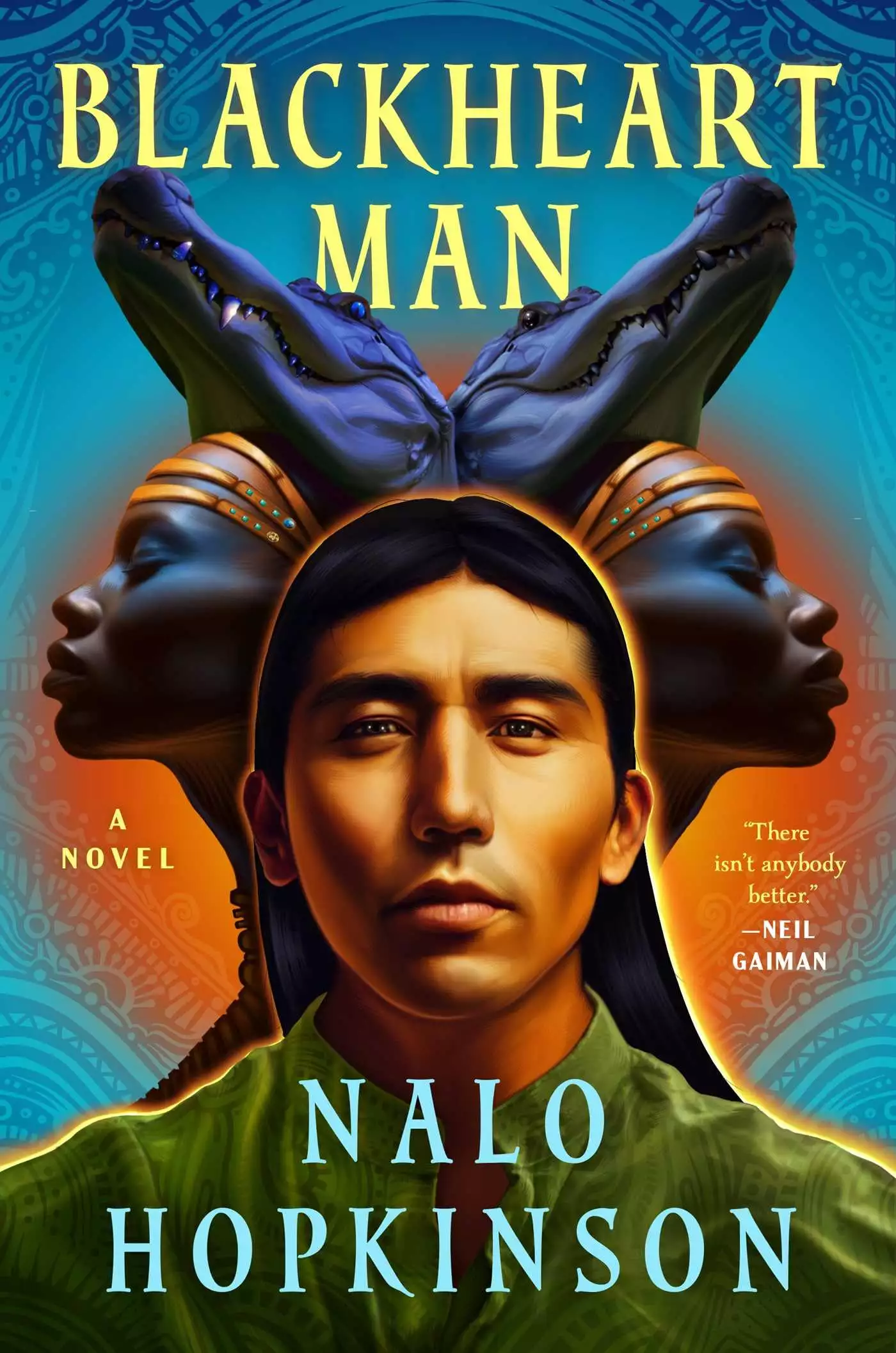

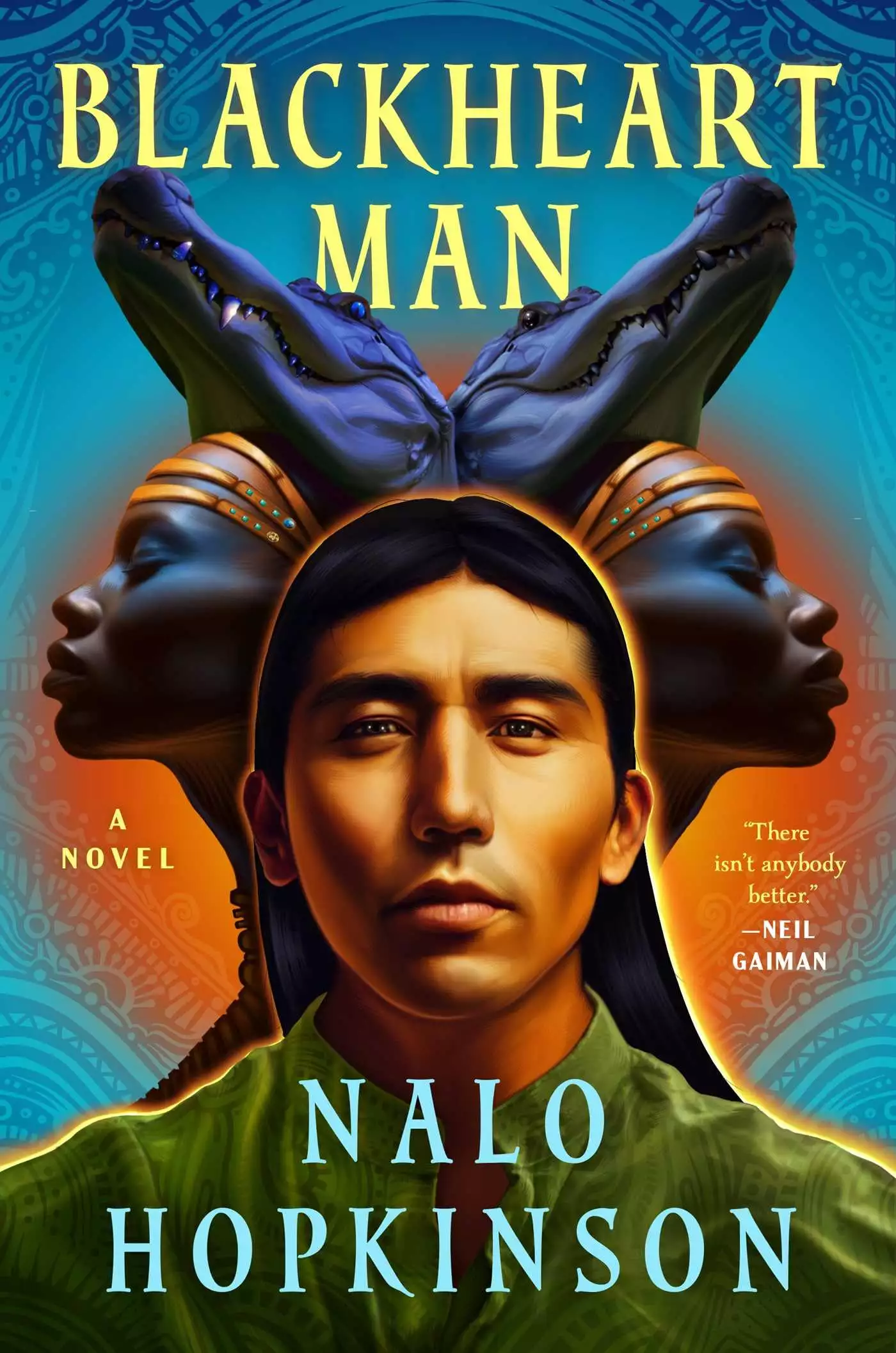

Blackheart Man

- eBook

- Paperback

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

The magical island of Chynchin is facing conquerors from abroad and something sinister from within in this entrancing fantasy from the Grand Master Award–winning author Nalo Hopkinson.

Veycosi, a scholar of folklore, hopes to sail off to examine the rare Alamat Book of Light and thus secure a spot for himself on Cynchin’s Colloquium. However, unexpected events prevent that from happening. Fifteen Ymisen galleons arrive in the harbor to force a trade agreement on Cynchin. Veycosi is put in charge of the situation, but quickly finds himself in way over his head.

Bad turns to worse when malign forces start stirring. Pickens (children) are disappearing and an ancient invading army, long frozen into piche (tar) statues by island witches is stirring to life—led by the fearsome demon known as the Blackheart Man. Veycosi has problems in his polyamorous personal life, too. How much trouble can a poor scholar take? Or cause all by himself?

Release date: August 20, 2024

Publisher: S&S/Saga Press

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Blackheart Man

Nalo Hopkinson

Chapter 1

Carenage Town, the island nation of Chynchin

HERE AT THE TOP of Cullybree Heights, the stone statue honouring the twin goddess Mamacona loomed out over the ocean. She was carved in the form of two caimans, standing back to back on their hind legs, clawed front legs reaching out to embrace or to scourge. The caiman facing seawards was Mamagua, her jewelled eyes and pointed teeth the deep blue of lapis. Facing inland was Mamapiche, eyes and teeth a gleaming black obsidian. Each sister had a powerful caiman tail curled around her feet.

The fore-day morning sea was a deep, cold blue. Mama Sea was cheerful on the surface of Her vast, shifting self; whitecaps dancing towards the port in fishscale recursives, like slatterns kicking up their skirts to show their knickers. But beneath those knickers, ah, what? Salty depths that had swallowed many a somebody who surfaced changed, or surfaced not at all. What might be down there in the deep? You didn’t need to sink too far into the water before the sombre blue shaded even darker to navy, then deep night, then full, cold blackness.

Veycosi shuddered. Best to let women be the fishers. Take to their rudders to ride the sea. They understood Her better.

Straddling the wide clay outlet pipe that took fresh water from the Cullybree Heights reservoir to the south side of Carenage Town, he scooted a little farther along it. He had to be quick. As soon as the sun was fully up, other people would start visiting Carenage Town’s big reservoir, whether maintenance workers, people hunting the iguanas that were plentiful in the brush up here, or people fishing the reservoir for frogs and mullet. Every so often, Veycosi knocked on the pipe. Each thump netted him a juddering thud, as when you knocked on the green rind of a watermillion to test its ripeness. He’d been right, then; there was water in this pipe, too, as in the other five he’d tested. That was well. But he could also tell that the water wasn’t moving; when he’d done this same procedure a few minutes ago with the five other massive pipes that fed the other areas of Carenage Town, he hadn’t even needed to thump on them. The water filling them was running so strong that when he straddled each pipe, he could feel the powerful thrum of the flow against his haunches, like the stroke of a masterful lover. In this sixth pipe, however, the water was still; there must be a blockage somewhere farther down.

Stale water made for ill humours. Every day the town elders didn’t let him act, they risked an outbreak of cholera or bottle leg disease in Carenage. And if South Carenage sickened, it could spread to North, West, and East Carenage, Blueing, and Cassava Downs.

Veycosi kept knocking against the pipe, advancing as he went.

Thud. Thud. Thud.

Thump.

A flat sound, with no answering resonance. Was that the blockage?

He moved forwards a little more, knocking the while. He hadn’t gone more than thirty handsbreadths when his knock fetched a third sound; a low, hollow clang. The quality of the sound told him that from that section onwards, the pipe was empty. And as he’d suspected, the blockage was right at the point where the pipe turned to begin its gentle dip down to Carenage Town’s south side. Likely a build-up of matter blown into the reservoir during Chynchin’s long dry season. Council members were addlepates, every last one of them. Refusing his petition to try out his idea for getting the water flowing again. Instead, they wanted to wait until the rainy season, which should arrive in a few sennights. The council hoped that the weight of extra water from the rains would flush the pipe clear. The histories sang of only a few times pipes from the reservoir had become blocked, and each time, the weight of water pressing against the blockage had quickly cleared it. But this time, it had been going on for months. In the meantime, South Carenage, the bustling centre of town, had to fetch water from the river in buckets. And there was an ever-present smell of rot from still sewers. Next it’d be mosquitos breeding, their larvae wiggling in the putrid water. Then sickness. Thandy, his and Gombey’s fiancée, lived there, in the centre of town. This thing had to be fixed, and now. He would make the air down there sweet again, make the water flow. Thandy would be proud and show him favour once more, as she used to. She’d seemed cool towards him for some weeks now. He had no idea why. He was training to be a chanter of knowledge that others might employ it. The council had reminded him he was a chantwell, and a student one at that. Said he was not an ingenieur. Said he shouldn’t be meddling in the business of builders.

Fuck that. He could reckon instructions as well as anyone with a brain. Could chant the first five chapters of Mauretaine’s book Of Divers Matters on Constructing Wells, Pipes, and Sewers, beginning to end and back again, the full tenor main part. He and his classmates had studied its song last year. But he hadn’t had to memorize the section on clearing blocked pipes; that part was for the sopranos of his line.

Veycosi was beginning to slaver around the selfsame book he’d brought out onto the pipe with him, clenched between his teeth. He released it into his hand and opened it to the place he’d marked by slipping a z’avocade leaf in between the pages. The vellum binding creaked as the book opened. The ancient handmade paper of the pages gave off the usual dusty library smell, so sweet and exciting to his nose, it nearly made him hard every time he scented it. The book’s handwritten ink was fading; good thing he and his line at the Colloquium were committing it to memory, setting it to music so the song might spread on the winds like Mamacona’s breath. That way, the knowledge the book contained might never be forgotten.

He reread the instructions on the page. Yes, rap on the pipes for soundness. He’d already done that and verified that it wasn’t cracked. Open the sluice of the blocked pipe. He’d done that before he’d mounted the pipe. Drop some dye into the reservoir water now, very near the inlet of the suspect pipe. Thence he must watch and see where it did and didn’t flow. Ingenious, that. He pulled the bottle of indigo out of his sleeve pocket, removed the cork, and emptied the bottle into the reservoir water, as close to the pipe as possible. Slowly, a thread of it began to spiral downwards, away from the spreading circle of blue on the surface and towards the inlet below. So the pipe wasn’t completely blocked. Presently, though, he saw his mistake in using indigo. Blue dye, blue water, sombre morning light. The thinner the indigo spread, the less he could see it, until he couldn’t make out the dye at all.

No matter. He’d learned what it had to tell him. Time for the next part of the instructions.

Veycosi humped back along the pipe, towards the service steps from the reservoir to the ground below. He refused to think on how his movement resembled that of a cat with a wormy behind. Good thing Thandy couldn’t see his undignified dismount from his water pipe steed.

Standing on the top step, he looked around. Still no one up here but him and the birds. Half-seen flashes of iridescence laced with brown and green, the cullybrees flitted around him in their endless, wheeling flight. Truth was, the council had another reason for waiting till rainy season to think about the blocked pipe. They didn’t want to risk disrupting the cullybree eggs and ruining the annual Cullybree Festival. The cullybree chicks would hatch soon as the season turned fully from dry to rainy. Already they’d had a slight drizzle or two this month, but it was tapu to disturb the cullybree nests. Laying cullybrees tipped their eggs onto moss-lined crags on the northeastern face of the Heights, a furlong or so farther off. The foolish had a way to say that touching a cullybree nest would bring the world to an end. Chuh. Credulous gullwits. Any road, he was nowhere near the nests. He would get this thing done, then be off tomorrow on the ship to Ifanmwe, where the Colloquium’s book trader was holding a copy of the Alamat Book of Light for him. That tome hadn’t been seen for near on five centaines! The Colloquium had thought it long gone, lost to the sea when the siege of Ifanmwe had seen that country’s fine library put to the torch. Seventeen hundred books and scrolls burned. The histories sang that the clouds above the burned shell of the Ifanmwe library had been black for three days with paper ash. Knowledge destroyed. It was abominable to even think on.

Veycosi had heard that in the mountains above Ifanmwe, two oceans away, it was so cold in their wet season that rain hardened in midair and fell to the ground as a fine white powder. He’d always longed to see that. And to taste it. Steli said they creamed the stuff with yak’s milk and honey to make a divine confection. Veycosi was soon to become a fully fledged Fellow of the Colloquium of the nation of Chynchin. He had only to fetch a rare book for the Colloquium Council. The Alamat book was the prize that would bring him closer to that fellowship. Bring it home, take the dreaming draught that would give him a Reverie, and then he would be a full chantwell. Once he was a Fellow, he would be free to travel the world, collecting and preserving the written knowledge of history. To be on the sea! He’d only done so once, as a youngboy. He still remembered standing at the bow, the tang of salt spray on his lips.

Back at the reservoir wall, he tucked the book into his sleeve, which was turned and hemmed to form a deep pocket. From the foot of the reservoir steps he fetched the three unfired clay jars he’d brought with him from the market, each about the size of a baby’s head. He had calculated it all, based on Mauretaine’s figures. Five measures of phosphorus powder in each jar. The water would seep in, react with the phosphorus, and explode. He was going to create a swell of water within the reservoir, perhaps five handspans high. The extra pressure would push more water through the pipes and hopefully clear the blocked one. It would take some little while for the water to dissolve the jars’ raw clay and ignite the phosphorus. That would give him time to get down off the cliff—briskly, mind!

Not that there was much danger. He had tried a version of this at one-fiftieth size. Based on that experiment, he had perhaps nine minutes to get down from Cullybree Hill. Add one minute for margin of error, and he still had plenty time. He might make it all the way down into Carenage Town before the thing blew, so no one would know he had caused it.

He grinned to himself. Of course they would suspect who was responsible. After all, when mischief came at the run to Carenage Town, wasn’t it usually he, Veycosi, nipping at its heels? But by then the water would be running again, and they would be grateful. And if they weren’t; well, he’d be long gone on a ship bound for Ifanmwe, headed for the marvels of iced cream and the Alamat Book of Light. He’d return with his standing well secure at the Colloquium, and his little jackanape forgotten.

Flush with the righteousness of doing a needful thing, no matter who would gainsay it, Veycosi rose to his feet on the large bole of the pipe. He dropped the three sealed jars into the reservoir. They bobbed on the surface of the water, which would soon begin to dissolve the clay. The jars began at once to darken with wetness. Now he’d best be gone down the hill. It was all safe, but prudence, valour, et cetera. Quick as he could, he minced along the pipe.

The sun was just about risen. Something in the ocean caught the corner of Veycosi’s eye.

There was a fleet heading briskly for the bay below. Some fifteen galleons; and flying Ymisen colours! Veycosi startled and nearly lost his balance. He daren’t fall into the bombed water! His arms pinwheeled, sending his squared sleeve flaps semaphoring around his body. His smooth leather slippers slid on the clay pipe. He tilted. Desperately righted himself as Mauretaine’s ancient book Of Divers Matters slipped from his sleeve, tumbled into the water, and disappeared from view. It was the only copy in existence! He shouldn’t even have removed it from the library. For a Colloquium student to actually destroy one of its precious tomes! He could well be drummed out of the Colloquium for this. His adventure had just progressed from jackanape to infamy.

Jittering in shock on the pipe, he considered for an instant diving after the book. Its parchment pages would remain intact, but even now, the inked words inside would be dissolving into the water.

The water into which he had just introduced three bombs. It would be folly to leap in.

The fleet would soon enter the bay. Its foremasts, mains, and mizzens rose like spears from the ships’ decks. Veycosi’s scalp prickled. Ymisen. The country that had stolen his Cibonn’ ancestors’ lands and press-ganged them into slavery, along with people from Ilife and some unfortunates from Ymisen itself. But the ships were flying trade flags. Since when had Ymisen decided to quit its sanctions on Chynchin?

Home! After so many years, to be home. Standing on the deck of the Ymisen ship the Empire Star, Androu couldn’t still his traitor heart from leaping in his breast at the sight of the graceful sweep of Carenage Bay, the cocoanut and gru-gru bef palms blowing in a gentle breeze, the cullybree birds circling on the drafts in the air above. So long since he had set foot on Chynchin soil.

The captain gave the order for the sailor to run up the flags that would signal to the rest of the fleet to break away. Those ships would put in at deserted Boar Island a short distance away. They would load up with fresh water, hunt boar and dry the meat, and wait until they were sent for. Then they would arrive in force and take this wretched island of Chynchin. Turn it back into Ymisen territory, of sorts. That is, if the new Ymisen regime would acknowledge Tierce’s right to succeed to the throne, now that it had deposed Tierce’s father.

The steersman longingly eyed the bay. They had been weeks at full sail. Standing nearby with the captain, Advisor Gunderson stared at the bay too, and grunted his relief.

Well he might. They would get their precious passenger safely to their destination after all. All this for a book. But the trip would bring Androu, finally, his revenge.

The captain called out, “Full ahead!” to the steersman.

So busy were Androu’s eyes taking in the sight of Chynchin Island that he nearly overlooked the small spinning swirls of foam a scant few ells in front of them. Two smaller circles lay in a line pointing at them, leading to the largest one, which was closest to the bay. When Androu did notice them, the back of his neck prickled. “Hard to!” he yelled at the steersman. “Now!” Gods blast it, they were about to run up on Mamagua’s Pearls!

The steersman squinted at him but looked to the captain for his orders. The captain and Gunderson gave Androu a suspicious glare. Damned Ymisen prigs like Gunderson would never trust him, for all that he had blood such as theirs running in his veins. “Heave to!” Androu barked. “You’ll have us run aground!” Fear-sweat crawled beneath his collar.

Datiao drew breath! At last! But straitway he met the blockage; no air to fill his lungs, no way for his chest to expand even had there been air in it. All he got for his pains was a hot honey-trickle of black piche sliding into his nose and tickling down the back of his throat. His body spasmed, but there was no way to cough so as to expel the piche. How long he had been embalmed this way in sludgy blackness?

Long enough for him to unlearn the habit of breathing. But it had come back to him just now. All it needed was air for him to practise the skill proper. Then the three bitches would rue their borning days.

Veycosi realised he had been standing still on the pipe, transfixed in shock at the sight of the Ymisen ships. He’d lost track of how much time he had before the water dissolved the clay jars. Nine minutes, fifty seconds? Nine thirty-eight? His heart swelled his throat near shut. Teetering a little, he hotfooted it to the end of the pipe, jumped down, and broke into a pounding run down the path. Nine minutes, twenty-two seconds? Twenty-one? The foot of the hill was looking farther away than it had on his way up here.

Eight minutes, fifty-eight seconds, fifty-seven… Soon, he was scurrying down the part of the footpath along the very edge of Cullybree Hill that led down to the town. Eight thirty-two… He glanced up to the top of the ridge, where the jars in the reservoir were surely dissolving.

There was going to be hell to pay for losing the book. Maybe he’d be able to fish it out once this was all over. Perhaps some of the words would have survived.

“?’Ware ships!” he yelled to the town below. Not that they could hear him at this distance. He leapt over a patch of prickly scrub that was barring his way. He skidded on slippery moss on the other side. His feet slipped out from under him. He landed hard on one hip, the breath exploding from his lungs. Before he could brace himself, he slid out over the edge of the cliff. His legs kicked air. He scrabbled at the ground, at the skittering rockstones his fall had dislodged, at anything, anything!

He managed to grab a sapling. It whipped through his hands, skinning his palms. Frantic, he tightened his grip. The greenstick sapling cracked, but didn’t break. He blinked dirt out of his eyes and looked up at it. Its roots were starting to pull free. He dug his elbows into the lip of rock and paddled his feet around, feeling for purchase. But there was only air.

He twisted his body to look down over his shoulder. Red dirt cliffside all the way to the water. The black, deep water.

Rocks dislodged by his fall were bouncing at speed down the cliff. One of the rockstones sprang away from the hillside. He was up so high, he didn’t hear the splash when it hit the sea surface. Sweat trickled down the back of his neck. His shoulders burned with the strain of carrying his own weight. If he let go, he would fall into the bay, likely crack his spine like a twig when he hit the water from such a great height.

There! One foot had found a solid place. He jammed the foot into a shallow crevice in the rock. A breeze ran chilly fingers up under his robe. He still couldn’t lever himself up. And he’d lost complete track of how much time had passed. “Help!” he bellowed, into the echoing bell of flesh made by his chest and arms pressed against the cliff face. A gusty updraft plucked at his hair and at the hem of his robe. His hands were slipping down the length of the sapling. Six minutes, forty-seven seconds left? Forty-six?

“Help!”

Androu clutched at the polished wooden shell he always kept on a thong around his neck, hidden beneath his shirts; his soul case. It had been with him from birth. Mama-ji willing, it would be with him when he died. Which might be this very morning, if they didn’t listen to him now. He cursed himself for forgetting about the Pearls.

He pointed to the left of the peaceful bay, to a narrow, muddy outlet of the Iguaca River. The river mouth had more twists and turns than Mamagua’s tail. “We mun go that way!” he yelled at the captain, over the sound of the creaking ropes. “North by northwest, fifteen degrees! Quick, man! Else we’ll founder on the rocks under us!” He indicated the line of eddying whirlpools. The sharp, hidden rocks of Mamagua’s Pearls had torn the hull out of many a would-be marauder ship. What appeared to be the easiest way to approach Carenage Town by water was in fact the most deadly. “And run up the trade flags, sharp now!”

Advisor Gunderson nodded his permission. The captain peered through his spyglass. “North by northwest, fifteen degrees!” he bellowed at the steersman, who hung hard over. No time to measure out their course change. His face lined with doubt, the steersman set the ship leaping past the bay on a course towards the narrow inlet.

Androu threw his own weight onto the wheel to help them hold their course. They swept past the Pearls, so close that the ship’s starboard side was almost in the first eddy before she turned. Androu could feel the drag on the wheel, feel her struggling to break free of the whirlpool. “Come along now, old girl,” he muttered to her as he and the steersman held the wheel to. “Ye’d make poor firewood, all soaked with salt as ye are. Take me home, girl.”

The ship shuddered and leapt free of the whirlpool. Androu blew out a breath, let his shoulders creep down from around his ears. He stepped back from the wheel. The steersman muttered a grudging thanks. Androu wiped his brow with his sleeve. “Put her into the bay, there,” he said.

Androu stood on the deck of the ship and watched as the place he’d fled in anger some two decades before drew him in again.

Home.

Datiao tried to close his thoughts to the old memory of being mired, still on his donkey, in hot, suddenly liquid piche where there had been a flat road instants before. Of the screams and the sucking noises around him as the others were bucking up upon the same fate. Of sinking chest-deep before he could even think to fight his way free. The manic dying struggles of the donkey below him, between his thighs. One of those thighs, pressed between the kicking beast and the engulfing piche, being snapped like a stick of sugarcane. The howl of agony that had filled his mouth with black, tarry ooze as the piche closed over his head. And then the desperate sucking and sucking for breath—

No. It was done. He had died, and now air was no longer sovereign to him. He would have wept, if he could.

But though he couldn’t cry tears, he could and did curse himself for losing his nerve as he’d ridden out with the foreign soldiers that day, disguised as one of them, to march upon his own fellows. Had he only kept muttering the witches’ protective chantson as he had planned, the road might have stayed solid under them and he might not be in this simmering hell, surrounded by the bodies of the defeated. By reflex, he snarled.

And the very corner of his upper lip twitched. Such a tiny movement that he might have imagined it. Still, he strained again to repeat it.

And did.

Would that he could smile fully, laugh, caper about with glee for the joy of it! He could not; not yet. But his mouth was beginning to move!

Not just his mouth; the slow return of sensation brought with it a steady ache to Datiao’s forcibly outstretched arm, its palm splayed open. But he blessed even that feeling. Against the sullen shifting of the piche, he had been moving his fingers, agonizing increments at a time, to grasp at the source of the object he could not see; the thing that had woken him again to this horror. The thing that was bringing life back to him, radiating from his outstretched hand to the rest of his body. Some while ago, three of his fingertips had just barely touched the edges of something solid. The power emanating from the object was glorious and terrifying in its strength. He had been reaching, straining to grasp it for oh, how long? He needed to curl his hand around the thing, whatever it was, to draw it closer to him. And in between, he never ceased trying to move the rest of him. He went on and on trying. Soon he would be able to form the words of the life-preserving chantson again, and when the thing for which he was reaching brought him back full to his capacities, the chantson would help him remain hale. If chance was with him finally, there were three blasted women he would show the meaning of rue in all its fullest. Not to mention that backwards piece of rock the escapees were pleased to call Chynchin. Running away with his fellow enslaved had eventually cost him his life, and for what?

He tried not to think on all the times before that life had returned to him, only to be wrested away again by the engulfing tar that still held him trapped as he died again, in the same agony of suffocation as the first time. He died, and died, and died. He supposed he’d been enduring like this for hours. This morning, his biggest worry had been whether he would survive the day. Now he feared he would be trapped for days, perhaps weeks!

He more felt than heard the deep sound that went gonging through the treacly piche, setting it to vibrating. What had happened above? Who was winning the skirmish between the soldiers and the village with its three witches?

There must be a particularly hot day’s sun shining down on the piche from above, melting it some. The shuddering of the slowly liquefying piche made his position change, just a mite.

He found he could stretch his reaching arm a little bit farther. Good. Good. He strained and stretched his fingers till he felt sure their sinews would part from their joints.

And he touched it, first with scrabbling fingertips. And then he managed to curl his fingers around it until he was clutching it tightly in his fist.

Now, up. He didn’t have much time. If he didn’t reach air soon, he only had minutes of this unlife left. Without air, he would spend those minutes suffocating, as he had the first time. Already he could feel his death agonies creeping up on him again. With a mighty heave, he clawed a gobbet of softened piche to one side. Desperation lent him strength. Slow as justice and as blind, he began to claw his way up to the surface of doomed Chynchin.

The uprooted sapling slid a bit, then caught between two rockstones, held by its root ball. Veycosi tested the strength of it. It seemed solid, for now. Six minutes, nineteen seconds. Perhaps.

There. A bit higher up the cliff face and a little to the right was a place he might jam his foot, if he could reach it. Praying to Mamagua in wordless terror, he pulled himself up by the sapling. His arms were trembling so from fatigue that he feared he wouldn’t be able to keep hold of it. But he had to. He started swinging his body side to side. He’d heard it sung that a pendulum would achieve a wider arc if a greater force were applied anywhere along its length. The force came from his body, from his determination not to fall and burst himself apart on the rocks below.

It took four sweeping tries before he was able to set his foot into the toehold, keep it there, and roll his body back onto the path.

Five minutes, thirty-nine seconds left? Thirty-eight? He couldn’t lie there. He had to warn Chynchin. He pushed himself to his feet with arms whose muscles screamed for mercy. He began staggering down the hill again. He kept moving until he was in the valley. The buildings of Carenage Town were only a few yards in front of him. There was a street-side alarm bell right around that corner. Lungs screaming, legs trembling, he staggered on. “Ymisen,” he wheezed.

Carenage Town’s grey sand high road stretched out in front of Veycosi now, far as the eye could see. The street was busy, as it ever was: shops and businesses receiving custom all along the sides; covered stalls down the middle, dispensing bootlaces, boiled sweeties, and the like; and horse, camel, tricycle, and donkey traffic clattering along the twin lanes. Everywhere, people going about their business. He wove through it all like a drunken man. Nearly got stepped on by a camel. His lungpipes burned like they’d been washed with acid. His vision was blurred and the street sounds were getting muffled in his ears. He feared he might faint before he accomplished his duty. He could see the emergency bell on its pole, only a few yards away. Just a few more steps.

He was nearly to the other side of the street when a hand on his shoulder neatly moved him out of the way. It was a guard in his official garb of gold-embroidered red buba on top and matching sokoto trousers. Veycosi could have collapsed with relief. He started to croak out his warning.

“Stand back,” the man said, his voice pitched to carry. Chuh. A chantwell with a phthisic could speak louder. Not Veycosi at the moment, though. He tried to insist, but his voice had shrunk to scarce the hiss of

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...