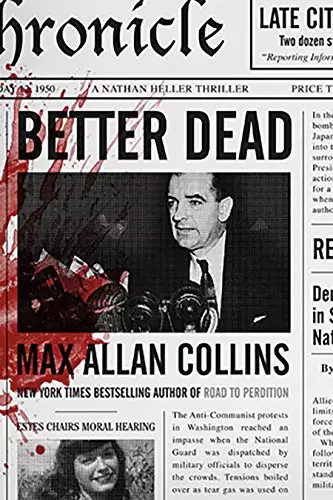

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

It's the early 1950's. Ju McCarthy is campaigning to rid America of the Red Menace. Nate Heller is doing legwork for the senator, though the Chicago detective is disheartened by McCarthy's witch-hunting tactics. He's made friends with a young staffer, Bobby Kennedy, while trading barbs with a potential enemy, the attorney Roy Cohn, who rubs Heller the wrong way. Not the least of which for successfully prosecuting the so-called Atomic Bomb spies, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg.

When famous mystery writer Dashiell Hammett comes to Heller representing a group of showbiz and literary leftists who are engaged in a last minute attempt to save the Rosenbergs, Heller decides to take on the case. Heller will have to play both sides to do this, and when McCarthy also tasks Heller to find out what the CIA has on him, Heller reluctantly agrees. His main lead is an army scientist working for the CIA who admits to Heller that he's been having misgivings about the work he's doing and elliptically referring to the Cold War making World War II look like a tea party. And then the scientist goes missing.

Release date: May 3, 2016

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Better Dead

Max Allan Collins

1

I was there when the Commies took over.

You won’t find it in the history books. But for one day in 1950, in a certain Wisconsin hamlet, the Red Menace came alive in America. I was only an observer, protected by an armband that identified me as such, provided by an armed guard at a checkpoint at a bridge leading into the downtown of Mosinee, population 1,400.

On this first day of May, there would be no dancing around streamer-flowing poles or handing out of baskets of flowers—in this little town (so perfect for a Saturday Evening Post cover) citizens would celebrate not May Day but International Workers’ Day, the worldwide Communist movement’s favorite holiday.

The timing of the takeover was in perfect sync with these early days of the Cold War. Just last August, the USSR had conducted its first successful atomic bomb test, while Mao Tse-tung’s People’s Liberation Army had kicked ass in the Chinese Civil War. Two months ago, at the Old Bailey in London, atomic spy Klaus Fuchs had been sentenced to fourteen years, a slap on the wrist to American eyes. Meanwhile, Wisconsin’s homegrown hero, Senator Joseph McCarthy, was making a national name for himself blowing the whistle on Commies in the U.S. State Department—all 205 of them. Or was that 81? Or maybe 57? Like Heinz.

At a precise predawn 6 a.m., a froglike form in metal-framed glasses, black fedora, and matching baggy suit strode to the front door of a modest brick home. Wearing a white armband that provided him with a sole splash of color (a red star), the squat scowling figure knocked four times with a fist, cannon shots that echoed in the early morning air.

Then the fat little man loudly announced himself: “This is Chief Commissar Joseph Zack Kornfeder! Open up at once!”

And he knocked four more times.

When he got no response, he shouted a chilling command: “Come out now—with your hands on your head! Or we’re coming in after you!”

Backing up the commissar’s demand were six heavily armed soldiers with red-star armbands. When Mayor Ralph Cronenwetter, still in his robe, pajamas, and slippers, finally answered his door, two of them dragged the middle-aged man out across his porch and down into the snowy street. Spring in Mosinee was in no hurry, the air chill, the trees skeletal.

Eyes wide in a doughy round face, his thinning hair askew, the startled mayor listened as Kornfeder informed the “enemy of the state” that his town had been taken over by “the Council of People’s Commissars.”

“Mosinee, Wisconsin,” Kornfeder decried ominously, a cigarette dangling, gangster style, “is now part of the United Soviet States of America!”

As two armed men dragged His Honor along, the commissar led his squad of invaders on foot to the police station, where they stormed in and yanked Chief Carl Gewiss away from his desk to deposit him in one of his own cells. A shouted third-degree interrogation began, conducted by a club- and knife-wielding pair in dark fedoras and matching overcoats.

Following this, the Mosinee Weekly Times was similarly stormed, its editor arrested and informed his paper would henceforth be known as the Red Star. By noon, an edition would be on the streets with Stalin’s picture sharing the front page with a Communist manifesto and a list of regulations, courtesy of the new regime.

Quickly the commissar and his bully boys took over the public utilities and then did the same with the town’s chief industry, the paper mill, where a sign was hung above the double doors saying, “Nationalized—Operated by Authority of the Council of People’s Commissars.”

Gradually wide-eyed citizens in winter apparel—topcoats, plaid hunting jackets, hats, gloves—filled the sidewalks, taking all this in, eventually spilling into Main Street. When enough gawkers had gathered to form a crowd, the quasi-military strangers with rifles and red-star armbands herded the good people of Mosinee into the village park, which they were stridently informed had been renamed Red Square.

Here a platform had been erected overnight, above which hung a banner that said, “One Party—One Leader—One Nation.” The citizens watched dumbfounded as the compact commissar, looking like a cruel caricature of James Cagney, stepped up onto the platform to a waiting microphone.

“The United Soviet States of America,” the amplified gravel voice intoned, the eyes behind the round-lens glasses as cold as the morning, “is nationalizing all industry. In addition, all political parties are now abolished, with the exception of the Communist Party. All civic organizations are disbanded as well. All religion is forbidden, all churches to be confiscated as representing an institution against the working class. Hereafter, you will live in an atheistic world, your minds unclouded by superstition.”

Here and there, citizens protested, only to be arrested and marched into a large vacant lot that had been transformed by barbed wire into a concentration camp. Adjacent was the American Legion Hall, where a banner read, “Commissariat of USSA Information.” As the day progressed, this concentration camp would grow to include the rounded-up likes of nuns from the Catholic school, local clergymen, and paper-mill executives.

But right now it was only 10:15 a.m. and the fun was just beginning. Up on the platform, the squat commissar announced that rationing was now in effect, and that restaurants would be serving black bread and potato soup only. For those who could not afford that, an outdoor soup kitchen would be available.

“Those of you who do not cooperate will be assigned to slave labor camps,” Kornfeder said, almost casual now in his recitation of atrocities.

Finally, gray-faced Mayor Cronenwetter was dragged up onto the stage at gunpoint. Still in his robe and pajamas, His Honor at the microphone rather pitifully read to the captive audience a prepared statement: “Police Chief Gewiss has been liquidated for failure to cooperate. I now urge all citizens to comply with the new socialist order.”

Throughout the day, most Mosineeans did comply, having been issued ration permits for food and gasoline as well as red-star lapel pins to signify their cooperation with the new regime. Anyone not willing to wear the lapel pin would be marched to the concentration camp.

Midday, an enforced parade was held with signs provided saying, “The Communist Party is the Only Party,” “Stalin is the Leader!” and the like. A big wooden circle with a red star that resembled a Texaco service-station sign (albeit superimposed with a hammer and sickle) was posted over the door to city hall, while all around town red-star-emblazoned flags were draped over doorposts.

Students were corralled in the high school gym and made by armed guards to stand in rows to hear lectures on Communist doctrine by visiting faculty. At the grade school, children were encouraged by teachers to join the Young Communist League, if for no other reason than the local sweet shop only sold candy to card-carrying members.

Elderly Reverend Will La Brew Bennett put up the biggest fuss, saying to those padlocking his church, “When America is taken over by Communists, I will hide my Bible in the church organ!” Then he was marched to the barbed-wire camp.

Elsewhere in Mosinee, Commie storm troopers entered the library with lists of books to remove, which they did, making a pile on the front lawn (apparently for eventual burning). Prices in the local A&P—renamed the Red Star Grocery—were raised to exorbitant rates, and the front window was painted with a borscht advertisement. Down the block, the movie theater replaced its current feature, Guilty of Treason (with Charles Bickford and Bonita Granville), with the 1945 Russian musical Hello, Moscow! (with Oleg Bobrov and Anya Stravinskaya).

Under third-degree interrogation, I would have to admit the musical was better than the Bickford picture, a turkey I’d suffered through a week ago back in Chicago. I mean, Hello, Moscow! was in color at least and had some catchy tunes.

I had slipped into the theater mid-afternoon when I’d become cold from the Wisconsin weather and bored with the Mosinee theatrics. I was pleased to find the popcorn machine hadn’t been confiscated, and that a good old American quarter could still get me a bag, a Coke, and change. Plus, the little blonde behind the counter gave me a smile for free. Shouldn’t she be attending a lecture on the new order at the high school gym?

Maybe they gave her a pass. Possibly even Commies needed somebody to hand out popcorn at the movies.

The mock coup, staged by the Wisconsin American Legion, was an elaborate daylong piece of street theater put on for members of the press, an international contingent that included television networks, newsreel outfits, wire services, Reader’s Digest, Life, and Time, and even the Russian news agency, TASS. A few dignitaries had been invited as observers, and I’d rated one of their rarefied armbands because the unofficial guest of honor for the Red takeover was Senator Joe McCarthy himself.

I was along as McCarthy’s guest because we’d done some business over the last couple of years and were friendly. When I learned he’d be back home in Wisconsin for a short stay, I arranged for an audience with America’s newly self-appointed Commie-Hunter-in-Chief. A client of mine needed help and McCarthy was the only path.

The business I represented was my own—the A-1 Detective Agency, of which I, Nathan Heller, was president. The firm had started back in 1932 as a one-man, one-room affair in a fairly dingy building at Van Buren and Plymouth, and had grown to include a Los Angeles branch office and an expanded main one in the celebrated Monadnock Building in the South Loop. Today I had half a dozen operatives, not counting my partner Lou Sapperstein (my old boss on the Pickpocket Detail) or our secretary Gladys Fortunato (with us since before the war).

You might wonder why the forty-four-year-old president of the A-1 would go chasing into the wilds of Wisconsin on behalf of a client when he had plenty of young operatives who could do that for him. But when it’s a United States senator like Joe McCarthy you make exceptions. Not that there really were any other United States senators like Joe McCarthy.

My forty-four years, by the way, were well-preserved ones, assembled into six feet and two hundred pounds, including features considered by some female types to cause no eyestrain. I was in a dark blue Dobbs hat and a gray Albert-Richard greatcoat with a black fur collar and lapels, its lining in (I’d been to Wisconsin in the “spring” before), over a lighter blue Botany 500 suit. Buying clothes on Maxwell Street was out these days, unless I needed a suit cut to conceal my nine-millimeter, which I had not brought to the party.

Good thing—it might have been confiscated by the Reds.

I admit to reporting some of the early morning activities secondhand, having flown in that a.m. from Midway to Downtown Wausau Airport, where a young aide of McCarthy’s waited in a black Buick to drive me the half hour to Mosinee. But I got there in time to fall in beside McCarthy where he lurked with the press on the periphery, as the mayor gave his surrender speech at pistol point to the assembled community in the park. That is, Red Square.

McCarthy wore neither Dobbs nor Botany 500—he was in a rumpled raincoat over one of those dark blue ready-made suits he seemed to buy in bulk. His red tie was showing—an irony that had escaped him, like most ironies did—and sported random polka dots that were really food stains.

He was grinning at the dark proceedings, and occasionally laughing under his breath—“Heh heh heh!”—in an almost girlish fashion that hardly suited such a bullnecked, barrel-chested, blue-jowled brute. His black hair was thinning, his eyebrows heavy and grown together over hooded sleepy eyes, his Bob Hope–ish nose flat from bridge to tip, a condition possibly dating to collegiate boxing days. For all that, the oval face on the big head could almost be called handsome.

No legislator had as many enemies in government as Joe McCarthy—then again, no legislator had as many followers outside of government. The junior senator from Wisconsin’s notoriety and popularity on the national scene had, in a matter of months, grown exponentially.

Nothing in McCarthy’s history hinted at the fame and power awaiting him. He’d been a chicken farmer and a grocery store manager, and had not gone to high school till he was twenty-one, although admittedly he’d then raced through. In college he majored in frat-house beer and poker, but did manage to graduate with a law degree. As a New Deal Democrat, he lost a run for district attorney of Shawano County; but as a Republican he became a Circuit Court judge. Running on a self-inflated war record (“Tail-Gunner Joe”), McCarthy became a U.S. senator in 1946.

Today, standing behind the newsreel and television cameras in the park, McCarthy was keeping an uncharacteristically low profile, begging off interviews, saying, “This is the Legion’s day. I’m just a spectator here. A guest.”

He explained to me from the sidelines, as we’d watched the mayor surrender his town, that the national American Legion was the real author of this Commie-takeover melodrama.

“Well, heh heh heh,” he said quietly, lessening the nasal drone of his baritone, “the Legion and J. Edgar. Everybody’s favorite G-man’s got the Legion wrapped around his little pinky, and good for him.”

As we passed the concentration camp on our way to a soup-kitchen lunch (vegetable—not bad), the senator pointed out among many unlikely prisoners in hats and business suits the owner/editor of the Mosinee Weekly Times, a tall distinguished-looking fellow in his forties who turned out to be retired Brigadier General Francis Schweinler.

“He was the local mover and shaker,” McCarthy said. “High mucky-muck on the state Legion’s Americanism committee. Really put it together.”

“Oh?”

The big bucket head nodded. “Sent a letter out all but ordering that citizens here join in. Told ’em they were being asked to play along for the greater good, and to voluntarily subject themselves to a few harmless inconveniences.” His small smile was almost a sneer as we took in the dazed faces of the concentration camp crowd, their breaths pluming. “Afraid the good people of Mosinee didn’t really know what they were getting themselves into.”

Later, as we watched the May Day parade, citizens trudging along with grim faces, a grinning Joe said, “This is wonderful—wonderful! A real object lesson in what it’s like to live under Communism. It’s no bed of roses.”

“Who are these troops, anyway?” I asked. Red-star-emblazoned jeeps were parked on either side along Main Street with helmeted rifle-bearing soldiers spotted all around.

“Ex-servicemen,” he said gleefully, “from all over the state. Seem to be having a darn good time.”

Maybe a little too darn good.

About that point I excused myself to take in Hello, Moscow! And two hours later, when I rejoined McCarthy in back of the camera crews, a dusk the color of the senator’s five o’clock shadow had fallen. A quietness settled in only to be shattered by bullhorns demanding everyone’s presence in Red Square.

There, under bright lights, the froglike commissar with his gangster overcoat and hat, wire-rim glasses and droopy cigarette began to speak again, extolling the virtues of Communism. “You have had today a small taste of the superior way of life represented by Soviet Russia!”

McCarthy, his mouth a slash in the blue-cheeked face, said quietly, “Good, isn’t he?”

“He’s a believable Commie, all right.”

“That’s because he used to be one. Name really is Kornfeder. He’s Czech, a real leader in the American Communist movement back in the thirties. Ten years ago he turned friendly HUAC witness. Now he’s what you’d call a professional anti-Communist.”

Took one to know one.

The commissar was still yakking when from nowhere the mayor—finally out of his pajamas and into a dignified suit and tie, hair neatly combed but face still gray—emerged to walk up onto the platform and push the commissar out of the way. Suddenly blue-uniformed police came up onto the stage and dragged off the protesting commissar, Kornfeder feeding corn to the wildly applauding audience to the very end.

With an austere dignified smile, the mayor said into the microphone, “I am here, good people of Mosinee, to announce that democracy has been restored to our fair city.”

More, even wilder applause now. Whistles and hoots and hollers.

As if in reaction, the mayor’s eyes widened.

But then he clutched his chest and seemed to be working at keeping his balance, as blurts of concern blossomed around the crowd. Finally he slumped to the wooden flooring, first on his knees, then onto his side, feet drawn up into a fetal position.

A collective gasp came up.

“Now what?” I asked McCarthy.

“That’s not scheduled,” the senator said, eyes disappearing into slits. Not smiling at all now. He took me by the arm. “Come on, Nate, let’s find my man and get out of here. This looks like something not to be a part of.”

Screams and wails were going up from the assemblage and we passed a screaming, wailing ambulance as in our black Buick we headed out of the liberated little community, making a getaway worthy of bank robbers.

* * *

Robbers back in Dillinger days were said to have escaped coppers via tunnels below the Hotel Wausau. But Joe McCarthy and I, in the downtown hotel’s restaurant off its Gothic cathedral of a lobby, weren’t hiding from anybody.

A scattering of diners exchanged glances and stole looks as the senator and I sat in a booth, the dark, rich wood around us typical of the hotel. McCarthy was working on a well-done porterhouse steak about the size of a hubcap and a buttered baked potato not much larger than a hand grenade. His short arms were pumping and his big hands were balled as he carved with knife and fork.

Delicate eater that I was, I had settled for a club steak, rare, and some hash browns with onions. McCarthy was drinking beer, and so was I. Schlitz. Made Milwaukee famous, you know.

We were inside an eight-story 1880s brick structure courtesy of Chicago architects Roche and Holabird—who turned out such little numbers as Soldier Field and the Art Institute—which might have made a Chicago boy feel at home. It didn’t. I had come to Wisconsin and Joe McCarthy’s table on a mission of mercy, or seeking mercy anyway, and right now my dinner companion didn’t seem merciful at all. Certainly the porterhouse was being shown none.

“There’s no question this friend of yours was in any number of Communist front groups,” he said between bites. When he said things like that, McCarthy fell into public speaking mode, forcing his baritone up into second tenor and emphasizing random words by dropping them back down.

“Youthful college days,” I said. “He didn’t know better. It was the Depression. You remember the Depression, don’t you, Joe? Lots of folks out of work. Weren’t you an FDR man back then?”

He grinned and had some more steak, chewed, swallowed, said, “But he’s a scientist. They’re the worst kind. Damnit, Nate, he worked on the Manhattan Project! Think what he had access to.”

“Early days at the University of Chicago. A minor figure, Joe. And back then the government gave him a full security clearance.”

“Quit assin’ around, Heller! In those days Uncle Sam let more Commies in than a half-ass henhouse fence does foxes. My boys tell me your pal is just another State Department Red.”

“He doesn’t work for the State Department, Joe. He’s a full-time professor now.”

“Filling empty young minds with dangerous propaganda.”

“No. Just physics. He does a little consulting with State, that’s all. Did your people find any Soviet ties?”

“… No.”

“Can you give him a pass, Joe? As a favor?”

He moved on to the baked potato, using the steak knife to cut down to and through the skin. “How are you and our buddy Drew gettin’ along?”

This was not the non sequitur it seemed. Reporter Drew Pearson, easily the nation’s most powerful syndicated left-of-center columnist, had once been very friendly with McCarthy, who had provided him and his man Jack Anderson with all kinds of inside dope from the Hill. But lately Pearson had been running negative items on McCarthy. The bloom could well be off the rose.

“We fell out,” I said, spearing some hash browns and onions, “after what he did to Jim Forrestal.”

Former Secretary of Defense Forrestal, a client of mine, had committed suicide in the midst of a heavy Pearson smear campaign. I’d stopped doing investigative work for Drew because of that.

“Glad to hear it,” he said, as he chewed potato. “As for your professor pal … let me sleep on it. I’ll let you know in the morning. When do you fly out?”

“Ten o’clock.”

“Come by my room at eight and we’ll have breakfast.”

As for the name of my friend at the University of Chicago, that isn’t pertinent to this narrative. Just in case you thought I was somebody who named names.

We were having apple pie when McCarthy’s slender young staffer came around and leaned in. His name I can’t give you because I don’t remember it, but I can tell you he had a nicer suit and tie than his boss.

“Senator … turns out Mayor Cronenwetter had a heart attack back there. He’s in the hospital in critical condition here in Wausau. Did you want me to arrange to go out there and…?”

The hooded eyes flared. “No. We, uh, don’t want to intrude on the family.”

The staffer nodded and disappeared so fast I expected a puff of smoke.

McCarthy said, “Damn shame.”

“Yeah. Too bad.”

“Really casts a pall on a great day.”

That evening I kept McCarthy company on a walking tour of downtown Wausau bars. He put away more beer than a bachelor party and yet circulated among the citizens, pumping hands like they were so many more porterhouses he was carving. I’ll give him this: He seemed to know them all by name, and he sat and laughed and talked with maybe a dozen of them.

Shanty Irish Joe had the common touch, all right. This was his base—Wisconsin’s German, Polish, and Czech voters. My Irish looks, courtesy of my mother, made me fit right in. Would I have been as welcome, I wondered, if my apostate Jewish pop showed more clearly in my features?

I also wondered if I’d be this welcome at Joe’s table if he knew my pop had been an old union man, a Wobbly who ran a left-wing bookstore on the West Side.

We wound up back in the hotel bar. I hadn’t had near as many beers as him, but enough to ask some questions that might have been ill-advised.

For example. “Joe, you used to be a Democrat. Civil rights, race relations … a damn moderate. How you’d get to where you are now?”

Drunk, he was in full-blown nasal speechifying. “I was a Democrat because I was ignorant. I know now they’re all a bunch of Commie-crats. Whether they know it or not, they’re part of a conspiracy on a scale so immense it dwarfs anything in human history.”

“You really believe that.”

“Damn right I do. And we have our friend Jim Forrestal to thank.”

“Oh?”

“He’s the boyo who clued me in about the Commie threat in government.”

He was also the boyo who jumped to his death from a high window in an insane asylum.

I said, “Well, it’s sure working for you. That speech you made in Wheeling, it really started the ball rolling.”

He didn’t deny it. He grinned a little and the droopy-lidded eyes glittered. “I got hold of something here, Nate, something really good. Something that’ll help me and our country.”

“But some of these people you’re accusing, Joe—you’re painting them with an awful wide brush.”

He shrugged and sipped from his pilsner. “If I’m right in the larger sense … and I am … it doesn’t matter a damn that the details are wrong.”

I was pretty drunk myself, but not enough to buy that bullshit. Still, I was sober enough not to say so.

* * *

The next morning I stopped by McCarthy’s suite at eight o’clock. The door was answered by the young staffer, who was in a silk mauve dressing robe. He looked tired but I didn’t sense I’d woken him.

“I’m afraid the senator’s indisposed.” He was blocking the way.

“Joe said to stop by and get him for breakfast.”

“Oh, I don’t think he’s in shape for that.”

I pushed through. “I need to talk to him before I head back.”

There was a living room area and two bedrooms. In one of the latter I found a nude Joe McCarthy sitting up in bed, pillows propped behind him, pouring himself a glass of something from a pitcher. I thought at first it was water.

But raising his glass, he asked, “Care for a martini, Nate?”

I will spare you any description of a naked Joe McCarthy, other than to say it would have involved hair, muscle, flab, and an appendage that was limp, which was fine by me.

“No, Joe, I better grab a quick breakfast downstairs. You want to throw something on and join me?”

“No. No, I’m fine.” He set the pitcher on the nightstand next to a little pile of pulp westerns. “Listen, I gave it some thought.”

“Uh, yeah?” I wasn’t sure what he was referring to, but I hoped he meant my University of Chicago friend.

“How did you know I was looking into that professor guy? That pinko scientist … how?”

“The private detective agency you hired to investigate him in Chicago is one I farm things out to sometimes. A colleague there clued me in. Professional courtesy.”

“Breach of trust, I say. Bastard shoulda kept that name to himself.” He grunted. “But you, Nate, you’re a good guy, looking out for a pal. What the hell. I’m gonna give him a pass.”

Right then he could’ve wrapped one of those sheets around himself and passed for Nero, even without a laurel wreath—thumbs-up, thumbs-down.

“I appreciate that, Joe.”

He grinned goofily and held out his hand for me to shake. Handshaking was a staple of his approach, though I found it as clammy as it was vigorous. And I wasn’t comfortable being that close to the naked senator.

Not that the image put me off breakfast—you develop a strong stomach in my line—and I made the ten a.m. flight just fine.

That was the end of my Mosinee adventure, but there is a postscript: Mayor Ralph Kronwetter, forty-nine, died on May 6. And Reverend Will La Brew, seventy-two, who had so indignantly promised the fake Commies he would hide his Bible, was found dead in his bed the next morning. A spokesman from the Mosinee American Legion called it “a terrible, tragic coincidence.”

But the doctor who’d treated them both said “the excitement and exertion of the day” had likely “contributed” to their untimely passings.

On the other hand, it was still relatively bloodless for a coup.

Copyright © 2016 by Max Allan Collins

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...