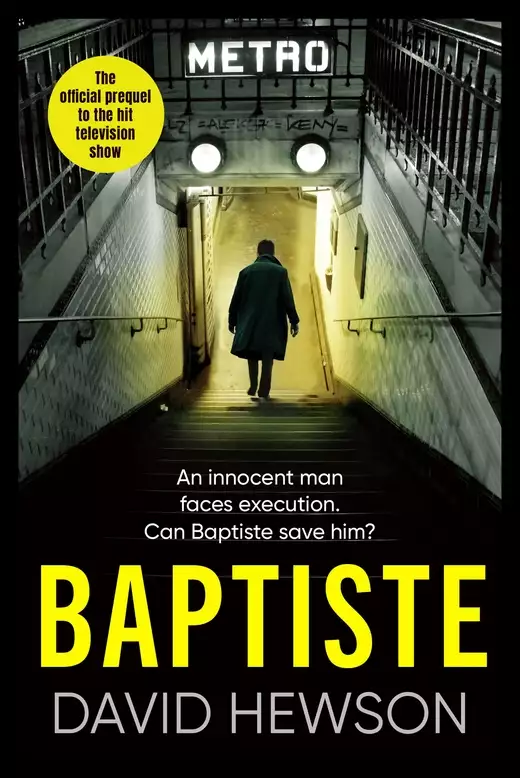

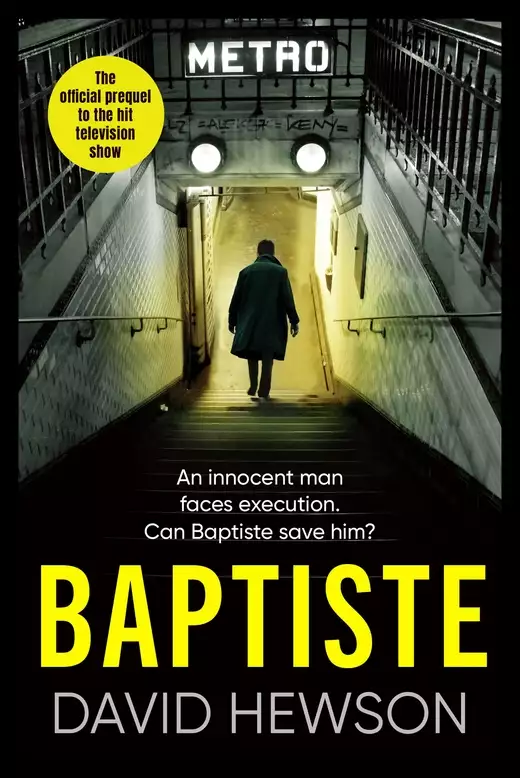

Baptiste: The Blade Must Fall

- eBook

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

The official prequel to the hit television show

AN INNOCENT MAN FACES EXECUTION.

CAN BAPTISTE SAVE HIM?

France, 1977. Baptiste is an intelligent but somewhat naive detective, sent to work in Clermiers, a town filled with corruption. A girl goes missing, presumed dead after bloody clothes are found close to an illicit party near an abandoned chateau. Baptiste believes he's nailed the culprit, the eccentric Gilles Mailloux. When he appears in court, the public call for the guillotine - and that's the sentence Mailloux gets. But as Mailloux awaits an appeal for clemency, he asks to see Baptiste, who's still haunted by the fact the girl's body remains missing. As the clock ticks towards execution hour, Baptiste begins to realise he may have made a terrible mistake...

Release date: May 2, 2024

Publisher: Orion

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Baptiste: The Blade Must Fall

David Hewson

Baptiste lit his seventh Disque Bleu of the morning and cast his eyes over the guillotine. There were only two or three still working in the whole of France. This one, a warder told him, was shipped by truck from Dijon three days before. The man who held the title of Chief Executioner had arrived early that morning and left it to a couple of workmen to assemble in the prison courtyard. It was smaller than Baptiste expected, perhaps because the only images he’d seen before were in history books. Marie Antoinette and the victims of the Terror meeting their ends on a public platform, severed heads held high by a triumphant sans-culotte to amuse a cheering crowd.

There was no stage for the rudimentary mechanism that was meant to take the life of Gilles Mailloux. No sense of theatre or much of an audience, though a small crowd of protesters had begun to assemble outside the high jail gates, calling for an end to state executions, singing songs, kneeling on the grubby cobbles and saying prayers. Capital punishment was rare, and probably soon to be abandoned given slow shifts in public opinion. Mailloux might be its last victim, in no small part due to his bizarre behaviour in court. That and Baptiste’s dogged handiwork in the case of the missing Noémie Augustin, raped and murdered at Mailloux’s hand the court decided, not that they yet had a body.

He couldn’t take his eyes off the guillotine. It seemed more like a piece of ancient farm machinery liberated from an agricultural museum than an instrument of death in the employ of the Ministry of Justice. A wooden frame like a giant child’s toy, ropes to raise the angled blade, sharpened and shining in the wan winter sun, a low plank bed for the prisoner to lie on, a half-moon cut out for his neck. Maybe there was a wicker basket somewhere, just like they had two centuries before during the Terror. There would be blood too, surely. Lots. And, waiting in one of the prison storerooms, a cheap pine coffin that would be brought out before the condemned man’s final moments.

One of the workmen yelled, ‘Hey, Marcel. Here’s to you!’ He had a cabbage, a big one, green and leafy, and was lobbing it through the air to his colleague. The other man caught it like a rugby player receiving a pass.

‘Trial run,’ he cried and placed it on the neck rest beneath the shadow of the frame. The other one pulled on the rope. The gleaming blade rose then locked in position at the summit. ‘Fais gaffe!’

One quick pull on the lever and they stepped back, laughing as the keen edge tumbled down with a squeal and screech, slammed into the cabbage, cleaved it in two.

‘Bon appetit.’ The one who worked the rope picked up half and threw it to his mate.

Baptiste finished his cigarette then threw it to the cobbled ground. One last time to plead with Gilles Mailloux. For some news, however grim, of the young woman he never once denied killing, not from the moment they took him into custody.

It only occurred to him when he reached the cell that there’d been an added act of cruelty on the part of the jail authorities. The guillotine was just a short walk from the barred window. The man who might soon die there could listen to the instrument of his end being assembled, tested, made ready for the final act. There was the hammering again. Nails. Wood. The scrape of metal on metal, that cruel blade being sharpened once more, cackles and jokes from the two workmen arguing over who got the largest share of the severed cabbage.

Gilles Mailloux looked much as he did that strange hot summer when Clermiers turned from a sleepy, little-noticed town in northern France into a hotbed of rumour, misery, and death. Tall and skinny as a bent scarecrow, with a gaunt face, sallow complexion, a little yellow over high cheekbones. Bulging bright blue eyes and unkempt greasy hair clinging to his scalp. The grey prison jacket and trousers they’d given him were a couple of sizes too big.

He nodded at the window: six bars, grubby with soot, paltry daylight barely filtering through, a spider starting to build its silky web in the corner.

‘Bonjour, Julien.’ Mailloux lounged back on his cell bed. ‘How goes it?’

Baptiste sat down on the cane chair set against the outside wall. He’d no idea how many hours were left before the sentence might be carried out, but he was determined not to leave empty-handed. Though, looking at Mailloux, he wondered if he was fooling himself. For a man on the verge of execution, he seemed remarkably calm.

The hammering ceased for a moment and one of the workmen barked out a nasty crack about whose job it might be to sweep up the blood.

‘It’s meant to be a kindness.’ Mailloux shuffled on the narrow, hard cell bed then stretched his skinny arms up against the brick wall painted a scruffy shade of olive. ‘Better than hanging. Or shooting. Or … I don’t know. I read they used to garrotte people, strangle them, in some places.’

‘I can never conceive that killing someone might be construed as a kindness, Gilles. Surely, you can’t be serious.’

Mailloux had turned twenty-three in jail, but one of the many oddities about him was how he looked so young yet sounded much older. Something in his background, not that Baptiste could imagine what that was. He’d managed to keep much of his true character, whatever demons drove him, well hidden, not just from the police but the one psychiatrist who’d tried to penetrate that hard, opaque shell and met little but silence and small talk. It was not a lack of intelligence. More likely a surfeit of it, derailed somehow. What learning Mailloux had was from his own efforts, not the school that had abandoned him at the age of fifteen, left him to survive as best he could on the grimy, impoverished Boulliers estate that sat on the wrong side of the river Chaume.

“You forget. I am the Monster of Merdeville. The Beast of Shit Town. I am serious. Deadly so, with every right to be. You know your history?”

‘History was my subject at university.’

‘Why? Why choose that?’

A good question. Mailloux always had them when he wanted. It was ridiculous that the best job he could find was working behind the counter of a petrol station at night, the ghost shift where, for hours it seemed, he did little but study books and read poetry.

‘I think because it helps me try to see where things go wrong. Where there’s a tear, a wound in the world, and how that wound might sometimes be healed, and occasionally made much worse. How, in the end, we turn towards good, though not easily on occasion, and not forever.’

Mailloux grimaced. ‘You sound like a priest. I didn’t summon one of them. I never would.’

‘I am no priest, I assure you,’ Baptiste said with the faintest of smiles.

‘Good. History. During the Revolution, the days of terror, the masters in Clermiers, the important men you understand, they’d drown people. Those icy grey waters. They’d herd them onto a boat, tie them down, then hole it midstream and sit back to enjoy the spectacle. The Noyades they called it.’

‘I believe that was Nantes.’

Mailloux laughed and shook his head.

Baptiste took out his pack of cigarettes. Almost half gone already, and he was glad there was a spare in his jacket pocket. He shuffled one out and offered it across the cell.

‘I don’t smoke. Surely you know that?’

‘I just thought. Now …’

‘Bad for you. Kick that habit, Julien. They may tell you it makes you look like a man. The truth is you smell. And maybe one day you’ll wake up and find there’s cancer running round your bones, raising tumours everywhere.’

Baptiste lit one anyway and immediately had a coughing fit. ‘Thank you for your concern.’

‘It’s not concern. It’s a statement of fact. Something Clermiers doesn’t much like. That place is good at keeping its secrets. Better than you know. History. Like I said, they drowned them in the Chaume. How much kinder to chop off a man’s head.’ His scrawny pale fist came down with force on his bony knees. ‘Bam! And they’re gone. Though …’

He hesitated and for a second or two Baptiste thought: Gilles Mailloux is scared.

‘Though what?’

‘I wonder if you die the moment the blade has done its work. Or live on a second or two after, watching the ground rise up to meet you.’

‘Who could know?’

He grinned, yellow teeth, sharp, vulpine. ‘The dead, of course. Don’t worry. I won’t come back to haunt you. To whisper secrets into your ear one dark, cold, lonely night. Tell you what I saw, what I felt in those last few moments. Ideas like that are for fairy tales, told in fairy palaces.’

‘There are more practical matters I’d rather hear right now.’

‘I’m sure there are. But you’re the one who put me here. That blade will rise at your bidding and …’

He drew a flat hand across his neck.

‘I don’t believe in executing people, Gilles. You wouldn’t be facing this impasse had you offered a little in the way of cooperation, of sympathy, of regret. And who knows? Perhaps it won’t happen. We’ll hear one way or the other soon enough.’

Mailloux’s face fell, all the fake mirth gone. ‘Those bleeding hearts should mind their business.’

It was a civil rights group that had petitioned the Élysée Palace for clemency, not the prisoner himself. He’d turned down the offer of legal representation, just as he’d refused to explain himself to the police and the court itself. All the same, the petition was lodged. An answer from the office of the President, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, was expected any hour. Gilles Mailloux’s life hung on nothing more than a telegram, a few words on a sheet of paper.

‘If that corrupt idiot is fool enough to sanction a so-called reprieve, he only sentences me to a different kind of death. A worse one.’ He nodded at the bars. ‘You think I’d survive one week if they let me wander among the animals out there?’

He’d been in solitary ever since his arrest. Given the publicity, much of it lurid, the authorities felt there’d be an attempt on his life were he to mix with other prisoners.

‘You’ve said nothing about Noémie Augustin since I arrested you. Now you ask to see me. Why?’

A shrug. ‘I was bored. A man on death row has the right to make a few demands.’

‘It’s not too late. Were you to shed some light on Noémie’s fate I could call the Élysée and tell them you were cooperating. That might carry some weight. They could delay matters until we’ve investigated further. A few more days, weeks. Months even. There’s always hope.’

Gilles Mailloux leaned forward. ‘Where does blood come from?’

‘I’m sorry …’

He looked at Baptiste as if he were an idiot. ‘Where does blood come from? What was it before?’

‘I don’t—’

‘From some kind of heaven? Or nowhere? Or maybe that’s the same.’

‘Gilles—’

A wry and knowing smile. ‘And where, in the end, does it go? Down a gutter. Into a drain. Is that where I’m headed?’

Baptiste wanted to spend the rest of this dismal day letting the fumes of a Disque Bleu circulate around his lungs. Then get a drink, red wine and cognac after. All that seemed distant, irrelevant at that moment. The image of the guillotine had been pushed from his head by another: Mailloux’s one outburst in court, after days of smirking, laughing, yawning and making faces at the judge and jury. He’d offered nothing in his defence, let alone a word of denial. There was just a single moment of furious speech, over something as ridiculous as a comic book. Mailloux had got to his feet in the dock and bawled out, ‘If this world had a heart, I’d reach through its ribs and tear the bloody thing to shreds.’ Then held out his hands like talons, ripping apart some invisible organ, laughing all the while, like the villain in a cheap noir movie.

It was a performance, an obvious piece of theatre, one Baptiste had watched in silent despair, understanding at that moment that Mailloux was surely headed for the guillotine.

‘The world does have a heart, Gilles.’

A moment, then, ‘Not for the likes of me.’

‘Just tell me where you left Noémie Augustin. Where we might find her. Give her mother the proper grief of a funeral. Release her from the hell you’ve sent her to. What reason could you have not to tell me now?’ He paused and wondered if any of this was going in. ‘Let me make that call. There’s still time.’

Mailloux threw up both hands in despair. ‘If only matters were that simple.’ He pointed at the door. ‘I would like a hot chocolate. A good one. And a croissant. With butter and strawberry jam. Something proper from a café, not the crap the canteen puts on tin plates here.’

‘I’m not a waiter.’

‘True. But you are a man who wants something.’ A weak wave of those skeletal arms. ‘Which, who knows, I may offer.’ That strange, unworldly smile. ‘If only you promise to stay with me to the end. The very end. To watch. To see me leave this shitty circus for good.’

Clermiers, Sunday, 18 July 1976

The tennis courts were by the river, three of them, changing rooms and a small shop. They belonged to the charitable organisation, Les Amis Dans L’Adversité, Friends in Adversity, based in its own clubhouse on the rise above. A villa from the late nineteenth century with a private restaurant, bar and lounge. A focal point where the men of Clermiers, the important ones, would meet to discuss business, talk politics and local affairs. Then, as the name suggested, feed a little support and money to the neighbourhood poor, mostly the wrong side of the river, before retiring to drink and dine to their hearts’ content.

Noémie Augustin, just turned nineteen, worked for the club as a waitress, lunchtimes and occasionally for their night events. The money was rotten but all she could find in the two months since she’d moved to the town. Still, they let her use the tennis courts for free, the one privilege that came with the uniforms the girls had to wear to work for the Amis.

Daniel Murray had to pay. He was an outsider, an English exchange student her parents had taken in as a brief lodger. One year older, a nice boy her mother thought, and her mother was usually right about things when she was allowed an opinion. Daniel didn’t seem to care her father was black, an immigrant from Martinique. Or that she had inherited a good deal of his looks. Clermiers wasn’t Paris. There were few immigrants in town. The fact her mother was white didn’t make much difference. Apart from her, the only other person of immigrant stock she’d got to know in the previous two months was Gilles Mailloux. Half-Algerian, his father long vanished, his mother scarcely at home much, Gilles was the local oddball. Likeable, always talking about books he’d read while working as the night attendant at the one petrol station on the edge of town. But tall and spindly, almost academic, not sporting at all. Never someone to join her at tennis.

She lined up to serve, right-handed, strong legs apart the way her idol, Evonne Goolagong, stood. That must have been why she sent an ace flying past Daniel on the far side of the court.

‘Not fair!’ he shrieked as the ball shot past him into the hedge behind.

‘Game, set, and match. Are the English all sore losers?’

‘This one is. I didn’t stand a chance!’

‘Of course you did. You just couldn’t take it.’

He squinted at her, shook a fist, then burst out laughing. Funny and good-looking as well. She’d started to wonder if there was a girlfriend back home. Someone he’d return to soon and forget about sorry little Clermiers where he lived briefly in a cramped spare bedroom for which he was paying an extortionate rent.

Not that he ever complained. He picked the ball out of the privet hedge, grabbed his racket and bag, and hopped over the net, catching his foot so he nearly fell flat on his face.

‘Clown. You did that deliberately.’

‘Got a smile out of you, didn’t it? Haven’t seen that for a day or two.’

He was perceptive, too. Right then, Noémie wished he wasn’t.

She watched as he picked up the rest of the balls. Back turned so she couldn’t see the long windows of the clubhouse lounge, or care if there were curious faces there.

‘What is it?’ he asked.

Everything was tidied away. He was as quick as he was relentlessly cheerful.

‘What’s what?’

‘You keep looking at that place back there.’

‘Do I?’

Daniel had only been in France ten days and seemed quite shy. He hadn’t talked much at all, but she’d got the impression Clermiers wasn’t what he expected. Her part anyway. Noémie Augustin’s family had landed up on the Boulliers estate, the wrong side of town. Before, they’d lived in a public housing flat in Calais while her father got his accountancy qualifications. At the end of the previous year, he’d been offered a job in Clermiers. It was an odd interview. She was called to it along with her mother, sitting through an anodyne bunch of questions in front of a man called Bruno Laurent and his elegant wife Véronique. Laurent seemed to own most of Clermiers and was willing to offer her father work on condition he start immediately, living in a bachelor flat the company provided. Family accommodation was harder to find, and it was only down to the generosity of his employer that she and her mother were finally able to join him that May, in a small house vacated, she learned, through a death.

Parts of Boulliers, a few worker’s cottages, dated back a century or more. Gilles Mailloux lived in a semi-detached among them, along with his mother when she was around. But most people were crammed into ugly concrete terraces and a few low apartment blocks put up by shoddy builders in the Fifties. Theirs was one of the few detached homes, a three-bedroom house, or, more accurately, two and a half, that belonged to Bruno Laurent, naturally.

Hauteville, the oldest part of Clermiers, set on the low hill on the left bank of the Chaume, was so much grander, almost a different place altogether. Elegant buildings, a neat town square, even a small theatre converted into a cinema, all built on the wealth of agriculture and the industries that once flourished in this grey part of northern France. A lot of that money had vanished, at least as far as the workers of Clermiers were concerned. But the traditional families of Hauteville still ran everything, owned most of the properties, owned people like her father too. That, Charles Augustin insisted, was the way of the world. The rich were always there, just like the poor. No point in trying to deny it, best to knuckle down, tug the forelock and hope for advancement somewhere along the way.

Ambition. Aspiration. Hope. Three things her father clung to. Three things many on the Boulliers estate would despise, along with those who sought them. They had their own name for the place: Merdeville. Shit Town. She hated hearing that. It wasn’t the place they were talking about. It was themselves.

Daniel sat down on the bench at the side of the court and patted the empty space next to him. ‘One more time. What is it?’

‘It’s nothing.’

‘Do you have any idea how infuriating you can be at times?’

‘That’s a bit cheeky from a lodger.’

‘A lodger who’s a friend …’

The walk from the club to home took nearly half an hour. The distance wasn’t so far but the route was blocked by the shuttered estate of the Château de Mortery, a local landmark long gone to ruin. This wasn’t the kind of château she’d read about in books, elegant, fancy, aristocratic. What little was visible behind the walls from the path outside looked like a castle of old, rugged, a fortress once.

After the château she’d cross the bridge over the broad and sluggish waters of the Chaume, then do her best to avoid the rougher parts of Boulliers. The week before, she’d engineered an excuse to leave her bike at home so the two of them could go that way together. She’d pumped the reticent Daniel for information, all of which came easily. He was from a middle-class home on the other side of La Manche, Folkestone. Father was a barrister, his mother had taught French at the local grammar school which was why his was so good. His sister Celia, two years older, worked for a travel company the family owned. All very different from the life Noémie and her family led. Charles Augustin was a hungry man, a bookkeeper by training though Laurent seemed to use him as a general dogsbody. It was for his family’s benefit, Charles Augustin always said, that he worked so hard, night and day, vanishing in the small hours for reasons he never explained with any conviction. In that case, she thought, he was a martyr for little purpose. There was never enough money, not that her mother complained. Martine Augustin seemed happy enough, content as she always said to ‘know her place’.

‘Nothing’s wrong. Nothing I can’t handle. Can we just leave it there?’

She opened her tennis bag and stuffed the racket inside.

‘What’s that?’

Damn, she thought. He saw.

‘What’s what?’

‘It looked like a black dress. Shiny. Like … you’re going dancing? And …’ He scratched his head. ‘Bananas?’

‘Have you been peeking in my bedroom, Daniel Murray?’

He was affronted. ‘Certainly not. I wouldn’t dream of it.’

She zipped the bag, stood up and shimmied for a moment, hips swaying side to side. ‘How very English you are. Maybe I do like to dance at times? Don’t you?’

He laughed. ‘Two left feet.’

‘I’m sorry?’

‘It’s an English expression. Probably doesn’t work in French.’

She didn’t move. Noémie seemed uncertain of something.

‘Are you OK walking back?’ he asked. ‘I thought you’d have brought your bike—’

‘Flat tyre.’

‘Oh. I assumed …’

‘I can walk. Those kids on the estate aren’t so bad.’

Daniel said nothing. She suspected he’d had a run-in with them somewhere along the way. A few nights before he’d come back from a walk looking flushed, grazes on his knuckles. Stumbled on a slippery path, or so he claimed, not that there’d been any rain. It was the hottest summer in years the weather people kept saying. Water shortages, bans on hosepipes. Hard to imagine someone losing their footing.

‘I’d come with you,’ he said. ‘But I can’t.’

‘It doesn’t matter!’

‘Someone’s over from England. I’ve got to meet them …’ He glanced at his watch. ‘Twenty minutes ago.’

‘Mustn’t be late for your girlfriend. Not if she’s travelled all this way.’

He groaned, folded his arms and gazed at her so directly she felt the blood rush to her cheeks.

‘Sorry. Didn’t mean to … be nosey.’

‘Of course not.’

‘Best be off then. You’re late.’

‘Maybe I could learn to dance,’ he said, getting up. ‘If I knew someone who could teach me.’ Then, not looking at her, he added, ‘We could give it a try. If you have the time. Talk about it over pizza. I’ll pay. I mean … only if you want … it’s up to you. Not pushing—’

‘Like a date, you mean?’

‘If … if …’ He was blushing. ‘If you’d like to see it that way.’

She grabbed the tennis bag and glanced back at the clubhouse. ‘See you back home. Whenever. I just …’ Noémie hesitated, and smiled, a little awkwardly. Then did the little dance again, more vivid, more enticing this time. ‘I’m just going to stay here for a little while. So hot. I need a shower.’

Daniel Murray headed off to town, puzzled, intrigued, perhaps disappointed. Maybe she’d led him on too much. Not that she was playing with him. Another day she’d have said yes. Gone for a pizza. Perhaps followed her feelings and let him get closer. Tried dancing, curing those two left feet. He’d be a good pupil, and a pupil was what she needed, more than a boyfriend just then. She’d learned enough already from the books she’d secretly bought online and borrowed from the town library. Now it was time to put all that into practice.

With Daniel.

A nice idea.

If only …

But nice ideas were fairytales in Boulliers. In Merdeville.

Mostly the place lived on airy fantasies and sometimes outright lies.

Furtive, whispered half-truths, like saying she needed a shower. Which she did. But that, Noémie Augustin knew, was only the start. The prelude to something she didn’t quite understand. A secret appointment that, whatever she’d been promised, had begun to fill her with dread.

There were five men watching the end of the tennis match from the comfort of the clubhouse dining room. The executive committee of Les Amis Dans L’Adversité. Fabrice Blanc, town mayor and chairman, next to him Philippe Dupont, the captain in charge of Clermiers’ small police station. Across the table Christian Chauvin, priest at the Église Saint-Vivien, and Louis Gaillard, local member of the Picardy assembly in Amiens. Bruno Laurent took the seat at the end as usual. He was the closest the town had to a local magnate, owner of a sugar beet refinery and two farms through inheritance, then, with canny and aggressive investment, the freehold of most commercial properties in Hauteville along with many residential homes across the region. In recent years Laurent had added property development and hotels to his portfolio. He was the one who kept the Amis alive with modest donations from his personal fortune, a generosity that had won him the thanks of national politicians and the occasional half-grudging gratitude of those his trickle-down of riches aided. The poor, it seemed to him, were rarely thankful, perhaps because they blamed him for their impoverishment in the first place. Still, it was an investment that paid dividends from time to time.

‘The business was acceptable,’ Blanc announced, closing the folder in front of him. ‘As usual, we’ve no need of minutes.’

Laurent groaned and rolled his eyes. ‘It seems to me all you people need is my money. How much have I shelled out for those losers in Boulliers today?’

‘Twenty thousand francs,’ Dupont said. ‘You’ll scarcely notice it, and most you’ll set against tax in any case.’

‘And all for an excellent cause,’ the priest added. ‘The young are the future of this world. They deserve all the help they can get.’

Dupont finished his glass of Evian then poured himself a calvados from the flask on the table and lit a cigarette. ‘If the young of Boulliers are the future then truly we’re fucked. Still, if you want to put up a hut and call it a youth ce. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...