- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

A warm-hearted, generous businesswoman discovers her dark side when she’s betrayed by both the younger man she thought was the love of her life and the best friend she’s always trusted—with shattering consequences—in New York Times bestselling author Mary Monroe’s final standalone novel set in the outrageously scandalous, colorful town of Lexington, Alabama.

The daughter of a hardworking restaurant owner, Louise Brooks always sees the best in people—and in helping them no matter how difficult her own life gets. She's lived through tragic loss and working in the family business, even after enduring a failed marriage and raising a child. So she's delighted when she finds a best friend in Della Thornton, a woman struggling with bad breaks and unlucky romances. Many years later, when Louise's father and her prosperous second husband pass away, Louise takes Della in and gives her a role in the restaurant as it grows more successful than ever . . .

Louise is now convinced lasting love is not in the cards for her—until she runs into handsome Malcolm Purdy. He's everything she could want—outgoing, charming, and attentive. Soon they become engaged. And although Louise is dismayed that Della and Malcolm hate each other from the start, she does her best to keep the peace between the two people she cares about and trusts the most . . .

But a chance encounter from the past shows Louise that neither Della nor Malcolm is quite who they say they are—and their deceit runs deeper and deadlier than she imagined. With her illusions in ruins, how far will she go to see justice served? And will her final shocking move cost her more than she’s willing to lose?

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

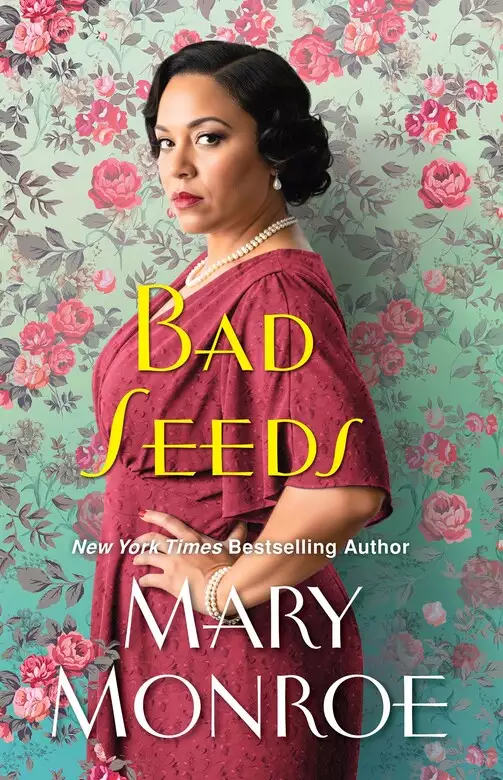

Bad Seeds

Mary Monroe

IF I HAD KNOWN THAT MY MAMA WAS GOING TO GET KILLED FOUR days after we’d enjoyed such a wonderful Fourth of July, I wouldn’t have lied to her and said I’d finished all of my regular chores. If she had known that I hid the basket of clothes, which I was supposed to iron, in my bedroom closet before eating breakfast, she wouldn’t have let me go shopping with her that morning.

“Louise, did you get one of them chickens out of the coop and wring its neck? I promised your daddy I’d make chicken and dumplings for supper.” Mama was standing at the kitchen sink washing dishes. I was sitting at the table fiddling with the buttons on my blouse.

“Yep! I’ll pluck the feathers off and gut it when we come back.” I hadn’t been near that chicken coop in our backyard. I planned to take care of the chicken when I got back from shopping because I’d be in the house by myself. As disgusting a job as it was, I’d do it in the kitchen. I was one of the most popular teenagers in the neighborhood. I would have died if one of my friends wandered into our backyard and seen me wrestling with a chicken. I hoped Mama didn’t ask me about nothing else, because I didn’t want to tell another lie.

She strummed the side of my face. “Thank you, baby. I wish I had five more like you. I guess since God took all my other young’uns, he made sure I ended up with the pick of the litter.”

Mama’s words made me feel even worse about lying. She would go to her grave believing that I was something I wasn’t. I breathed a sigh of relief, before she could ask me anything else, because Daddy shuffled into the kitchen, moaning and rubbing the side of his head. His thick black-and-gray hair looked like a dirty mop. He snorted and rubbed the back of his head before he said anything. “Effie, you ain’t got to work for that Daily woman today, so you’re free to work for me, right?”

“Right. She had to go to Mobile today to check on her mama. Miss Daily is such a sweet lady, she said she’d pay me for today, though. So I’m free to work with you for a few hours.”

My parents co-owned the only colored-owned barbecue place in Lexington, Alabama. It was located at the end of the block that led to our part of town. Tiny’s Rib Shack shared a little old building with a colored-owned ice-cream parlor on the other side of the thin wall. The floors and the counter was spiffy, and there was always a great big jar of pig feet on the counter at both places that customers could enjoy for free.

“Good. Then don’t you and this gal spend all morning at that five-and-dime store. I need both of y’all to help me out today. Louise, you can mop the floor and wash them dishes. Effie, you have a way with white folks, so I want you to work the cash register. I’d rather get a whupping, than to do that every day,” Daddy said in a gruff tone. My head started spinning. If I had to work, that meant I’d have to skip out early so I could make it back to our house in time to deal with that doggone chicken before Mama and Daddy got home.

Mama didn’t waste no time responding. “I’ve been working in white folks’ houses off and on most of my life, so I know how to keep them mollified. If we don’t, they’ll find a way to shut Tiny’s down, like they did my nephew’s bait shop.”

I would never forget that incident. Three years ago, when I was eleven, my cousin Rufus sold night crawlers to some young white boys. They went home and told their daddy that he had shortchanged them. The boys went back to the bait shop with their mama and daddy and confronted Rufus. He swore he’d gave them the right change, so then the daddy got madder because my cousin had “accused” them boys of lying. That was when all hell broke loose. They trashed the bait shop and beat Rufus up so bad, he almost died. The police didn’t do nothing about it. We was still reeling over the lynching of a blind colored man the month before. All we could do about the violence we had to put up with was pray, nurse our wounded, bury our dead, or move up North.

I hated hearing about the evils of white folks so often, but it was something that colored people had to deal with every day. A simple thing like a shopping trip downtown could lead to all kinds of trouble for us. If we said something a white person didn’t like, or looked at them the wrong way, we got accused of “harassing” them and could end up in jail or dead. But me and my folks knew our place, so we never had no trouble, but that would soon change. After my cousin recovered from his beating, him and his pregnant wife moved to Pennsylvania and never looked back.

It was hard to believe that some white folks in the South hated us so much they made up a set of rules we had to follow. We wasn’t allowed to eat in most of their restaurants, live in their neighborhoods, and we could only shop in some of their stores on certain days. A heap of colored men from all over the South had joined the army. We was proud of them, but joining the military hadn’t given them no more rights than they’d had before. Daddy and Mama was still mad about something we’d read in the newspapers back in April. President William Howard Taft had expelled colored soldiers in San Antonio, Texas, for protesting segregated seating on city streetcars. “Colored men are serving this country only to make life easier for white folks,” Daddy had griped, more than one time. Even with all the evil we had to put up with, I still enjoyed my life. I had fun going fishing and blackberry picking with Mama and my friends. Next to fishing, shopping was my favorite pastime.

Despite the segregation laws and the violence against us, it pleased me to know that not all white folks was mean. Some of the ladies Mama cleaned and cooked for was nice and generous to her. When she attempted to leave her job working for one particular family, the wife cried like a baby and begged Mama not to quit. That nice lady gave Mama a hefty raise and drove her to and from work until the family moved to Texas. The white folks who came to buy barbecue was real nice, too. Some would get their orders and instead of leaving, they’d stay and chat with us about fishing, hunting, and stuff like that. The ones who brought their kids around my age with them would ask me to take the kids out in the back and play tag or hide-and-seek until their orders was ready.

The original owner of Tiny’s was a man named Melvin Broadnax. Everybody called him Tiny because he was really short and thin. From behind, he looked like a ten-year-old boy. He had retired at the age of eighty-five and left the business to Daddy and his best friend, Dewey Brooks. They had been equal co-owners ever since. Both of them had started working for Tiny when I was still in elementary school and had promised him they would take care of him for the rest of his life, because he didn’t have no family left. He’d been born into slavery, and by the time Lincoln freed the slaves, all of Tiny’s folks had been sold or was dead.

Mama used to go to Tiny’s house and help him out when she didn’t have to work. I would volunteer to go read the Bible to him, wash and comb his hair, and do other chores he couldn’t do no more. When Tiny got too disabled to live by hisself, my folks moved him in with us. We didn’t have but two bedrooms, and I didn’t want that old man to sleep on the couch or a pallet.

“Brother Tiny can have my room, and I’ll sleep on the couch,” I offered.

“Baby, that’s so nice of you to make such a sacrifice. I’m so pleased to have such a caring and generous daughter,” Mama told me.

My mama was a small-boned, copper-colored woman, with a heart-shaped face and big brown eyes. A heap of folks said she was pretty. My skin tone was the same as hers, and I had a small frame at the time, but my face was not as pretty. I looked like Daddy in a wig-hat. I didn’t like sleeping on the couch, but it wasn’t for long. Tiny died three months later. When Mama couldn’t find jobs working for wealthy white folks, she worked at Tiny’s.

Daddy owned a Model T Ford, which he used to make deliveries to people who put in big orders for barbecue. Even though money was tight for everybody, folks always had enough to treat themselves to some of the best barbecue in town.

White folks who didn’t want to pay what the white-owned barbecue joint across the street from the courthouse charged came to Tiny’s. The ones with money usually sent their colored servants to pick up their orders, but some came in person. If colored folks was already in line waiting to order when whites came in, we had to put the coloreds on hold and wait on the whites first. We didn’t like it, but we did everything we could to keep the peace.

My family was fortunate. Tiny’s had so many regular customers, we didn’t have to pinch pennies like most of our friends. I loved hanging out at Tiny’s. I wasn’t even fazed when I got scolded for going into the kitchen to pinch off the ribs when I was supposed to be mopping or sweeping the front area. When I finished my chores each day, I got paid a nickel and could eat all I wanted. I was so deep in thought I didn’t realize Daddy was talking to me.

“You done gone deaf, gal?” he asked as he snapped his fingers in my face.

“Huh? Oh! What did you say, Daddy?”

“I told you to make sure your mama picks me up a plug of chewing tobacco.”

“You done told me that ten times already.” Mama rolled her eyes and snickered.

Daddy didn’t chew tobacco every day, and when he did, Mama refused to kiss him. Otherwise, they showed each other a lot of affection. Every time I turned around, they was hugging or giving each other love taps and whatnot. I was glad they never fussed or fought like a lot of the other married folks I knew. I prayed for a husband who would treat me as good as my daddy treated my mama.

Mama and Daddy did all they could to keep me happy. I hadn’t got a whupping since I was a toddler, and I had more clothes and spending money than all the rest of my friends put together. But things couldn’t get no worse for some colored folks in Alabama. The families who couldn’t find enough work to cover their bills had to move in with relatives. There was several one- and two-bedroom houses on our block where ten or more extended family members lived. The folks who didn’t have no family to turn to ended up living in tents in makeshift camps on the outskirts of town. Our churches did as much as they could to help the poor. I counted my blessings every day.

The trolley didn’t provide service to the colored neighborhoods yet, so Daddy let Mama use his car to drive downtown that day. We lived only two blocks from Tiny’s and he didn’t mind walking. The stores we was going to were also within walking distance, but Mama had bunions on her feet almost as big as hen eggs, so she didn’t like to do much walking.

She parked in the alley behind the stores we planned to visit. We had just walked out of the alley when a loud truck rolled down the street in the wrong lane. There was a man behind the wheel who looked like he was half asleep.

“That man is going to kill somebody!” I yelled. The next thing I knew, a little white girl around eight years old in a white dress with red roses all over it, ran out of the dress store we was in front of. She chased a rubber ball into the street. The girl didn’t see the truck weaving in her direction. Mama screamed and ran toward the girl. She grabbed her and pushed her to the sidewalk. Before Mama could get back out of the way, the truck slammed into her so hard, her shoes flew off her feet.

A WELL-DRESSED WHITE WOMAN WITH LONG BLOND HAIR RAN OUT of the dress store. There was a wild-eyed look on her narrow face as she grabbed the little girl’s arm. She only glanced at Mama lying on the ground as she guided the little girl back into the store.

Half a dozen other white folks had stopped and started gaping at Mama. One of the men bent down and fanned her face with a rolled-up newspaper. A woman took a handkerchief out of her purse and wiped blood off Mama’s face. “Be still, ma’am. You’re going to be all right,” she said in a soft tone. She looked up and down the street. “I’m sure somebody who can help you will come along soon.” These people did all they could for Mama. They couldn’t take her to the hospital because it was only for white folks. They wasn’t brave enough to put a injured colored woman in their car and drive her to our clinic.

A teenage boy opened the truck driver’s door and pulled him out. He must have drunk a gallon of moonshine, because I could smell it on him as the boy and another man helped him to the curb. He plopped down, cussing and complaining about Mama damaging his fender.

When the two people who had tried to make Mama more comfortable stood up, I squatted down and cradled her in my arms. “Mama, I’m here.” Not only was my voice trembling, my hands was, too. “I need you, so please don’t die.”

A few minutes later, a ambulance, with its siren screaming so loud it hurt my ears, parked in front of the truck driver. Two hefty men, dressed in all white, piled out and trotted over to him. He kept yelling that he was all right, but they loaded him into the ambulance and sped off. The woman who had wiped blood off Mama handed the handkerchief to me and I laid it on a gash on the side of her face.

“Keep sopping off the blood until help comes, sugar,” the nice woman said.

“Thank you, ma’am,” I mumbled. I sniffed, and the next thing I knew, tears was sliding down my face.

It wasn’t too much longer before I noticed a elderly colored man approaching. Brother Green came dragging along the side of the street with his rickety old mule wagon. As soon as he stopped, all the white folks left. I still had the lady’s handkerchief, but it wasn’t doing much good. There was so much blood, the white handkerchief was now completely red, and so was the front of my white blouse.

Brother Green lived on the same block where we lived. He was so decrepit it took him a couple of minutes to climb down from his wagon. He was panting like a big dog as he hobbled over to me and Mama. With his beady eyes squinted, he hollered, “Sweet Jesus! What the devil happened, Louise?”

I was still crying, but managed to tell him what had occurred. “Can you take us to the clinic?”

“For sure! Help me load her up,” Brother Green wheezed.

Mama was a little woman, so it wasn’t hard for me and him to carry her to his wagon and hoist her up into the bed. “My daddy’s car is parked in the alley,” I told Brother Green as I climbed up next to Mama and laid her head in my lap.

“Well, after we get Effie to the clinic, we’ll round up your daddy so he can go get it.”

We had to take our sick, wounded, and dead folks to the colored clinic, a small gloomy-looking building near the colored cemetery. Lexington was such a small town, almost everything was close by, no matter where you was at.

Brother Green’s mule was old, so the wagon moved real slow. Cars, bicycles, and carriages was whizzing around us so fast it made me nervous. Some of the drivers was cussing and giving us mean looks. To keep from getting beat up or worse, Brother Green left the main street and went down back roads and alleys, like most of the people who got around on mule wagons. It took us so long to get to the clinic that by the time we got there, Mama wasn’t moving no more and her eyes was closed.

After two of the workers got her inside, a doctor advised me and Brother Green to leave because it would be a while before Mama could have any visitors. Me and him went back to his wagon and headed down the street. “Is she going to die?” I asked with a huge lump rising in my throat.

“I don’t know, child. All we can do is pray,” Brother Green answered with his voice cracking.

Everything else happened so fast, my head was spinning. We picked up Daddy from Tiny’s, took him to retrieve his car, and he went to the clinic. Brother Green dropped me off at my house. After I changed out of my bloody clothes, I paced around in the house and cried and prayed until Daddy came home that afternoon.

Daddy was only forty-eight, but he looked older. His face was still handsome, but he had a heap of wrinkles. There was a pea-size black birthmark on the side of his dark pecan-brown face. His deep-set black eyes was red, so I knew he’d been crying. I knew he didn’t have no good news to tell. He wouldn’t even look at me as he shuffled to the couch and plopped down.

I couldn’t even feel my feet moving as I stumbled over and sat next to him. “Is Mama dead?” I asked in a flat tone.

Daddy still wouldn’t look at me. “Effie was a good woman,” he muttered.

We had Mama’s funeral four days later. Telephones was such a luxury item, most folks couldn’t afford them yet. Daddy had to send telegrams to Mama’s five out-of-town siblings to let them know, but they was all too sick, old, and too broke to take the bus or the train to Alabama. The only one who was able to make it was one of Daddy’s three brothers and one of Mama’s female cousins. They lived only about a hour away in Mobile with their families.

I went through that day in a daze. There was nothing I hated more than funerals. Last year, I’d attended Daddy’s mama’s funeral, and a week later, his sister died. The rest of my grandparents had passed when I was a toddler. I couldn’t believe how much my family had shrunk since I was born.

I loved my family, especially my parents. They had worked so hard to give me a good life. I prayed that I would have a strong marriage like they’d had. When I told Mama that last year, she was flattered and made me promise that I’d never cheat on my husband. “A unfaithful wife is a blight in God’s eyes.”

“What about unfaithful husbands?” I asked.

“Oh, men are so weak, they can’t help themselves and God takes that into consideration. And another thing I want you to promise me is that you won’t never live with a man, unless you’re married to him. Living in sin is another blight in God’s eyes.”

Mama had also advised me to marry a older man. “They are wiser and easier to live with than younger men. And they have more to offer. I turned down proposals from two boys my age to marry your daddy. I was fifteen, he was thirty. Them two boys was field hands still living at home. Your daddy had a nice house and a good job at the slaughterhouse. Keep that in mind when you start thinking about marriage.”

“I will,” I said.

Mama had been so generous and nice to everybody, she was one of the most beloved women in town. A week before she got killed, she told me, “Louise, we’ve been blessed, and I don’t want you to ever take it for granted. Don’t be stingy when somebody in need comes to you for help. If you got what they ask for, give it to them. God will bless you even more.” That was a promise I intended to keep.

A week after Mama’s funeral, I was at Tiny’s sweeping the floor when the front door flew open, just before closing time. A young white man, with jet-black hair and a scowl on his face, stormed in, waving a shotgun. He sprinted across the floor and got right in my face.

“Where is that nigger at?” the man roared.

Daddy, Dewey, and Vella Mae, the woman who did most of the cooking, was in the kitchen cleaning up. Fridays was always real busy, which was the reason Daddy had made me come in to do a few chores.

I dropped the broom and stammered, “W-which one?”

“The one married to that wench who damaged my daddy’s truck!”

Before I could answer, Daddy trotted out of the kitchen, wiping his hands on a dishrag. “Can I help you, sir?”

The man glared at Daddy and put the barrel of the gun up to the side of his head. “I ain’t leaving here until you give me the money to have my daddy’s truck fender repaired!” As bad as things was for colored folks in the South, every now and then, something happened that blew me away. But this took the cake.

I had never seen my daddy look so scared. His eyes was stretched open and he was trembling so hard, I thought he was going to collapse. “Uh … uh … how much do I owe you, sir?” he asked in a meek tone.

Instead of answering, the man strode behind the counter and stopped in front of the cash register. “Open this damn thing!” he ordered.

“Yes, sir. Right away, sir,” Daddy said as he stumbled to the cash register.

As soon as the drawer slid open, the man’s face lit up. “That looks like enough,” he growled. “Give it here!”

“H-how much?” Daddy whimpered as he stared at the shotgun. “I’ll take it all and we’ll call it even.”

I stood glued to my spot, still clutching the broom, as Daddy pulled out every dollar bill we had made for the day and handed it to the mean man.

“I’m a fair man. You can keep them coins,” he said with a snicker. And then he looked toward the kitchen and sniffed. “Fix me a plate of them ribs and I’ll be on my way.”

“Yes, sir,” Daddy whimpered. Having a gun pointed at him and getting “robbed” shook him up real bad. A few minutes after the man left with the money and a plate filled with ribs, Daddy went home and never worked at Tiny’s again. He gave up his partnership with Dewey, but he promised him that I could continue to mop the floor and wash dishes after school and he’d still pay me a nickel each time like Daddy had.

Daddy didn’t like to sit around doing nothing. Six months after he’d stopped working at Tiny’s, he got hired to work for Phil Donnelly, a used-to-be judge. Daddy’s job was to help their live-in nurse take care of Mr. Donnelly’s elderly father. The old man had both of his legs removed because of some disease I’d never heard of and had to be lifted in and out of bed several times a day. On top of that, Daddy did a lot of handyman-type chores around the house. Mr. Donnelly had been a judge for thirty years and had recently retired so him and his wife could do some traveling. They liked Daddy so much, they even offered to take him along on a trip to Europe. Daddy had never even been out of the state, so going out of the country was a big deal to him. He started packing a week before the trip.

“I wish your mama had lived long enough to see me going overseas and coming back to America on that new big boat they named Titanic.” He grinned as I helped him pack.

A day after Daddy had packed his suitcase, we learned the news that the Donnellys had died in a car crash the night before. Daddy was so overwhelmed with grief he didn’t eat for two days. The double funeral was three days later. Colored folks wasn’t allowed to attend, not even the couple’s numerous servants. I rode with Daddy when he insisted on driving over there and parking across the street from the church long enough for us to say a prayer.

“Well, I guess I’ll never get to see Europe and ride on that big new boat that was going to bring us back to America,” he said on the way home.

“Daddy, you don’t like riding on boats. Even when we go fishing at the lake,” I reminded.

“It was so nice of the Donnellys to invite me, I couldn’t tell them I didn’t want to go because I didn’t like being on boats,” he replied. “Oh, well. Maybe this is a blessing in disguise for me.”

It was a blessing in disguise for Daddy. In April, we got more devastating news. The big new boat that was supposed to bring the Donnellys and Daddy back to America—which the newspapers had said was unsinkable—sank in the middle of the ocean after it hit a iceberg.

1912 to 1913

I HATED BEING A ONLY CHILD. BUT I HADN’T ALWAYS BEEN ONE. I used to have two older brothers and a baby sister. Eight years ago, my oldest brother died when he stepped on a rusty nail and got a real bad infection. He had skipped school that day to go fishing, so he never said nothing until it was too late. Mama and Daddy took him to the clinic, but he couldn’t be saved.

A year ago, my other brother went to visit a friend, who lived on the outskirts of town, and he never came home. He had just turned fifteen the day before. His body was found a week later by a hunter. Somebody had stabbed him in the neck. He didn’t have no enemies that we knew of, so the sheriff said he couldn’t do anything because he had nothing to go on. We never found out who killed my brother. My sister was four years younger than me. When she was just a year old, she went to sleep one night and never woke up. Mama and Daddy was so scared they’d lose me, too. They treated me like they’d bought me by the pound. I got everything I asked fo. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...