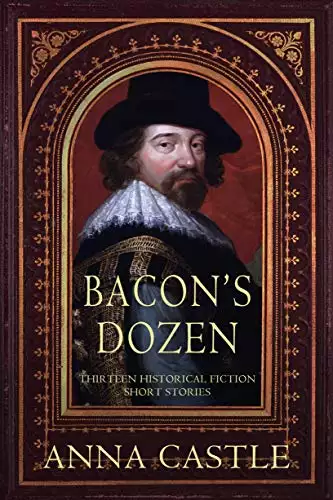

For Want of a Book

[All Francis Bacon wants is a book, but when he reaches his favorite bookshop, the printer drags him into a murder investigation. This story first appeared in the October, 2017 issue of Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine.]

London, February 1586

The cold wind blowing down Paternoster Row snatched at Francis Bacon’s hat. He grabbed it before it flew from his head and pulled it firmly down, hunching forward into the wind. He ought to be snug in his bed with a fur-lined coverlet and a hot posset, absorbed in his study of Niccolò Machiavelli’s works, not risking his health out of doors so early on a March morning.

But in order to develop his thoughts about realism as a moral stance, he needed to re-read Lucretius’s De rerum natura, and he didn’t have a copy in his chambers. Someone at Gray’s Inn undoubtedly owned the work, but his fellow barristers had been out of sorts with him since his recent promotion to a seat on the governing bench. Never mind that his late father had been the Lord Keeper of the Great Seal or that the position was merely probationary. Never mind that he knew as much about the law as the rest of them put together. The outcry had risen, loud and bitter. “He’s only twenty-five! He’s barely passed the bar! He’s never argued a single case in court!”

The fuss would die down when a fresh scandal came along. In the meantime, he had a compelling desire to read a book he did not possess and was thus driven out of doors to trudge through the icy London streets.

His favorite bookseller, Oliver Brocksby, traded under the sign of the owl at the top of the row. The street behind St. Paul’s Cathedral, usually crowded with men in legal and scholarly robes, seemed deserted. Was it too early for the shops to be open? The sun had been up at the point when he realized he needed the Lucretius, so he’d simply dressed and hurried out without giving a thought to the time. He hoped it wouldn’t turn out to be Sunday — or a holiday.

Never mind; Brocksby lived above his shop. He’d be there. Now if only Francis could persuade him to let him have another book on credit . . .

He tucked his chin against an icy gust and pushed on the door, half expecting it to be locked. But it swung open as if pulled from the other side, drawing him abruptly into the shop, straight into the arms of the bookseller.

“Thank God it’s only you, Mr. Bacon. You must help me!”

Francis blinked at him, uncomprehending and blinded by the dimness. “I’m hoping you have a copy of De rerum natura that you could —”

“Not now! The most horrible —” Brocksby flapped his hands in distress. He peered through a gap in the shutters and then turned the key in the lock, trapping them inside. “You must help me, Mr. Bacon. I don’t know what to do!”

The fine hairs rose on the back of Francis’s neck. The man seemed completely bereft of his wits. “What do you want from me?”

“Come! Come!” Brocksby plucked at Francis’s cloak to draw him deeper into the shop. “I beg you!” He now stood between Francis and the door.

There seemed no alternative but to placate him. Francis followed him through the bookstore and into the printing shop behind it. The familiar acrid smells of ink and metal struck his nose as he passed the threshold. Brocksby and his partner operated a single press on which they produced broadsides, pamphlets, and the occasional small book. The press dominated the long, narrow workspace, leaving scarcely enough room for two slanted typesetting tables, a pair of lines for hanging wet pages, and a laying-out table. Racks of type and various tools hung upon the walls over cases of different sizes and qualities of paper.

Small windows set high in the back wall admitted a thin gray light, augmented by the yellow glow of a candle. Brocksby led Francis around the press to the delivery and storage area inside the back door and stopped short. “Look! Look!”

At first, all Francis could see was a chaos of papers and bound books strewn everywhere, littering the tables and floor, as if the back door had been blown open to admit the March wind. He spotted a large barrel lying on its side against the wall near the door; perhaps somehow it had fallen over and the papers had been shaken out as it rolled around. He’d never seen the normally tidy workshop in such a state of disarray.

Then he saw the man lying sprawled upon the floor, face up, red blood soaked into his puce-colored doublet, his dark cloak bunched beneath him.

He recoiled with a strangled groan. His hand clutched his chest as he stepped backward until his thighs struck the press. “What have you done?”

“It wasn’t me! You must believe that, Mr. Bacon.” Brocksby clasped his hands together. “I could never do such a terrible thing.”

The bookseller’s brown eyes were wet with tears and his thin cheeks drawn with shock. His face was so familiar, with its drooping moustaches and straggling beard. Francis had known him since he’d first moved to Gray’s Inn, some six or seven years ago. He’d explored all the bookshops in London and discovered that the sign of the owl was the best place for works by the more obscure philosophers, especially those from Italy. He’d spent many a pleasant hour over the years discussing such works with the proprietor.

He felt he understood the temper of the man. In some ways, Oliver Brocksby was a better friend than any member of Gray’s Inn.

Francis’s heart slowed to its normal pace, but he still couldn’t bring himself to look back at the man on the floor. “Who is it?”

“My partner, Edward Kellett.”

“Kellett?” Francis risked a glance and noted the dark spade-cut beard of the man he’d known. “What happened?”

“I don’t know. I came down this morning and found him in the midst of this mess. He must have been stabbed, judging by the blood.” His voice choked on the last words.

“He looks like he’s been dragged.” Francis pointed at the way the bunched cloak trailed toward the door, leaving a long red smear.

Brocksby gazed down at the body, wringing his hands. “I confess I tugged at him a bit, trying to lift him. I don’t know what I thought I could do. He’s too heavy for me, and he was most certainly dead when I found him.”

Now Francis noticed dark streaks on the bookseller’s buff apron and red spots on his white cuffs. He grimaced in disgust, thinking that the man could not look more guilty. Might he have deliberately muddled the circumstances? “Where’s your son?”

“In Cambridge, thanks be to God, with our apprentice, looking for something to publish. Something cheap and popular, I hope. Although if they’d been here, they might have prevented this.” Brocksby waved helplessly at the disaster. “I sleep upstairs, at the front of the house. They can’t have made much noise, whoever they were.”

“You must call the coroner,” Francis said, “and inform the sheriff. Thieves must have followed him in from the alley . . . But where did all these books come from?”

“Frankfurt. The spring fair.”

“Of course.” Kellett always went to both the spring and autumn book fairs to look for bargains, like works that might appeal to English readers in translation. “When did he get back?”

“Last night, I suppose, after I went to bed. Which is not long after sundown on these cold nights.” Brocksby shrugged apologetically. “I usually take a draught. I haven’t slept well since Mary died.”

His wife had died a year or so ago. Francis had rarely encountered her. “Wouldn’t you wait up for Kellett?”

“I didn’t expect him until tomorrow.” He shook his head. “Today, that is. This afternoon. They must have sailed a day early. The weather, I suppose. That’s our barrel.” Brocksby pointed at the owl branded on the lid, which lay near his feet. “I came down to open the shop as usual this morning and heard a noise back here. I found the door wide open, banging in the wind. It was so dark I had walked across and closed it before I saw him.”

“You must call the sheriff,” Francis repeated. “Although I imagine the thieves are snug in their lairs by now.”

Brocksby gave him an odd sidelong look. “I’m not so sure it was a thief, Mr. Bacon. Look! He still has his purse.”

Francis couldn’t bring himself to look again. “Is it empty?”

Brocksby sucked the fringe of his moustache, then heaved a sigh. “I’ll see.” He approached the body, bent down, and gingerly touched the small leather pouch tied to Kellett’s belt. “No. It’s full of coins.” He reached for it again but drew his hand back, fingers twitching.

“You’d better take it,” Francis said. “It will only disappear into the coroner’s men’s pockets.”

Brocksby gritted his teeth and untied the purse. He held it up by the strings to display its sodden condition. “It’ll have to be washed.” He scanned the cluttered print shop and spotted a clay bowl. He removed the pestle and dropped the blood-soaked purse into it. Then he covered the bowl with a rag and pushed it onto a high shelf.

He returned to stand near the body and shot that sidelong glance at Francis again. “I can’t call the coroner, Mr. Bacon.” His looked down at his twisting hands, but his gaze strayed toward a heap of small books.

“What was in the barrel, Brocksby?”

“Nothing!” He clucked his tongue. “Nothing terrible. Odds and ends. Paper, of course. English paper is so dear these days. And a few works we thought we might have translated, that might sell. Kellett wrote me that he’d found a nice collection of minor Latin poets at an excellent price. Hadrian, Tiberianus. Not well-known in England and thus perhaps a novelty. You’ll like them, Mr. Bacon. Not that you’d need translations, of course, but the ordinary reader . . .”

The man was babbling. That barrel had transported more than fine paper and minor poets into England. Francis stooped to pick up the nearest sheet with writing on it and read the first few words aloud. “I do not want to be Florus, to walk through the taverns . . .”

Latin poetry. He studied the mess, observing many small volumes bound in plain pasteboard. Palm-sized, sextodecimos. He picked one up and turned to the title page: A methode, to meditate on the Psalter. A Catholic guide to prayer, banned in England since the pope had issued his famous bull against the queen.

“Oh, Brocksby!” Francis shook the thin volume at the bookseller, who had backed himself into the corner and wrapped his arms around his chest as if for protection. “Why?”

“Money. Money. What else? They fetch such a good price here, and they’re so cheap on the Continent. Pay a shilling, charge a pound.”

“As much as that?”

Brocksby fluttered both hands. “I exaggerate. But it’s a very profitable venture, or so we’ve heard. We’re desperate, Mr. Bacon. We haven’t got a single lucrative printing patent, and the books we like don’t sell. We love philosophy as much as you do, but so few share that interest and those who do rarely pay —”

He cut himself off, pressing his lips together, but Francis could finish the sentence for him. Rarely pay their bills. He felt a twinge of guilt. “Even so, Brocksby. You must know these books are illegal.”

“Barely. Besides, they’re scarcely different from a Protestant prayer book.”

“No, Brocksby. They’re different.” Not much, but every spectrum necessarily had its endpoints. These guides to prayer anchored the mild end of the scale of prohibited literature; at the other extreme stood blatant exhortations against the lawful queen. The authorities might view even this minor offense as a stepping stone toward greater ones. They would ask, “What will this bookseller attempt to import next? Jesuit calls to active rebellion? Scurrilous personal attacks on England’s noblemen? Lewd works from Italy?”

Francis sighed, taking note of the bloody thumbprint marking the bowl holding the blood-soaked purse, the streaks on the floor showing that the body had been moved, the overturned barrel, and the evidence of a violent assault. And there stood the bookseller right in the middle, fearfully wringing his hands over his bloodstained apron.

“I can’t call the sheriff, Mr. Bacon, at least not until I’ve done something with these books. And even then they’ll accuse me. Kellett and I — we’ve been arguing lately, loudly and often, debating what to do.” He shot a dark glare at the east wall. A more successful rival held the premises next door. “I’m sure everyone on Paternoster Row knows we’re up to our ears in debt.”

He clasped his hands together, raising them in a gesture of supplication, and faced Francis with watery eyes. “You must help me, Mr. Bacon. I beg of you.”

“What can I do?” Francis took a step back. “I assure you, my influence is not as great as you might imagine.”

“But you’re a gentleman. You’re a barrister. You’re a bencher at Gray’s Inn. They’ll have to listen to you.”

“But what would I say? I know no more about this tragic act than you do. No, I’m sorry. There’s nothing I can do.” He shook his head and both hands for emphasis, then turned to find his way out of the workshop.

Brocksby closed on him swiftly, grabbing his sleeve. A stony glint appeared in his dark eyes. “Help me, or I’ll tell your mother about your Brunos.”

“You wouldn’t!” Francis possessed several works by the controversial and possibly blasphemous Giordano Bruno. The books Francis had were mainly about mnemonics, but Lady Bacon was a Calvinist of the very strictest variety and disapproved of almost anything written by an Italian or a Catholic, lapsed or otherwise. He would never hear the end of it.

“I’m desperate, Mr. Bacon. All we need is an explanation that points the finger of blame away from me. You’re so clever. You’ll see things I can’t.”

The two men, equal in height, stood nose to nose and locked eyes. Francis knew Brocksby could sense him wavering and strove to strengthen his resolve. He could weather his mother’s outrage. He’d been doing it all his life.

But Brocksby had his measure. “I’ll forgive your bill.” The edge of his lips turned up in the tiniest of smiles.

Francis blinked at him, calculating rapidly. He owed what — upward of five pounds? “A blank slate?”

Brocksby circled a palm in the air. “Wiped clean.”

Francis sighed, defeated. He took a few steps to gaze down on the body, which now seemed more forlorn than horrible. “Did Kellet have any enemies?”

“I don’t think so.” Brocksby shrugged. “Unless you count his wife.”

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved