- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

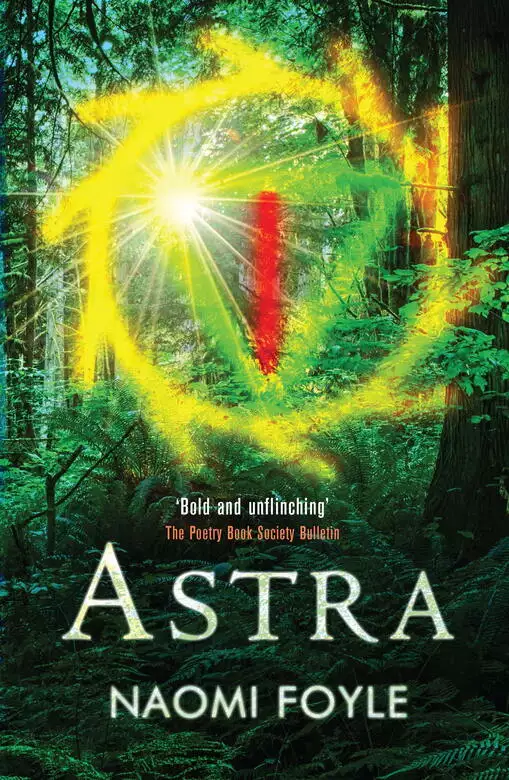

Synopsis

Like every child in Is-Land, all Astra Ordott wants is to do her National Service and defend her Gaian homeland from Non-Lander 'infiltrators'. But when her Shelter mother tells her that this will limit her chances of becoming a scientist and offers her an alternative, Astra agrees. If she is to survive, Astra must learn to deal with truths about Is-Land, Non-Land and the secret web of adult relationships that surrounds her.

Release date: February 6, 2014

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 464

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Astra

Naomi Foyle

Her name floated up to her again, rising on the simmering spring air through a dense puzzle of branches, light and shade. But though Hokma’s voice rasped at her conscience like the bark beneath her palms, Astra pretended – for just another minute – not to hear it.

Gaia had led her here, and all around her Gaia’s symphony played on: ants streamed in delicate patterns over the forest floor, worms squirmed beneath rocks and logs, squirrels nattered in the treetops and birds flung their careless loops of notes up to the sun. Immersed in these thrilling rhythms, alert to their flashing revelations, Astra had discovered the pine glade. There, craning to follow the arc of a raptor circling far above, she’d spied a branch strangely waving in a windless sky. And now, just above her in the tip of the tree, was the reason why: five grubby toes, peeking through the needles like a misplaced nest of baby mice.

Yes. She hadn’t been ‘making up stories’, as Nimma had announced to the other Or-kids last week. It was the girl. The infiltrator. The spindly Non-Lander girl she’d seen slipping behind the rocks near the brook, wild-haired and wearing nothing but a string of hazelnuts around her neck. The girl had disappeared then, as sinuously as a vaporising liquid, but today she was rustling above Astra in the tree, dislodging dust and needles, forcing Astra to squint and duck as she climbed higher than she ever had before. The girl was real: and nearly close enough to touch.

The girl probably thought she was safe. Thought the dwindling pine branches couldn’t support Astra’s sturdy seven-nearly-eight-year-old body. That Astra would be scared to climb higher. That she, the skinny forest child, could just wait, invisibly, her arms wrapped like snakes around the trunk, until Astra – hungry, overheated, tired of hugging the prickly tree – had to descend and go home.

But if she thought any of that, she was wrong. Dead wrong. Tomorrow was Security Shot Day, and Astra wasn’t scared of any kind of needles. Nor was she too hot. A bright bar of sunlight was smacking her neck and her whole body was slick with sweat, but she’d filled her brand new hydropac with crushed ice before leaving Or and she watered herself again now through the tubing. Refreshed, she reached up and grasped a branch above her head.

Keeping her feet firmly planted on their perch, she hung her full weight from this next rung in her tree ladder. Yes: thin but strong; it wouldn’t snap. She eyed another likely hand-branch, slightly higher than the first – that one, there. Good: gripped. Now the tricky bit: looking down. Careful not to focus on anything beneath her own toes in their rubber-soled sandals, she checked for a sturdy branch about level with her knees. That one? Yes. She lifted her left foot and—

‘Owwww’.

A pine cone thwacked Astra’s right hand, ricocheted off her cheek, and plummeted out of sight. For a terrible second, Astra’s knees weakened and her fingers loosened their hold on their branches.

But though her hand stung and throbbed, and her heart was drilling like a woodpecker in her chest, she was still – praise Gaia! – clinging to the tree. Breathing hard, Astra withdrew her left foot to safety and clamped her arms around the trunk. The crusty bark chafed her chest and, like the steam from one of Nimma’s essential-oil baths, the bracing sap-scent scoured her nostrils, clearing her head. At last her pulse steadied. She examined her hand: the pine cone hadn’t drawn blood, but there was a graze mark beneath her knuckles.

The Non-Lander had inflicted a wound, possibly a serious injury, a crippling blow. One at a time, Astra flexed her fingers. Thank Gaia: nothing seemed to be broken. She’d been aiming to kill or maim, hoping to knock Astra clean out of the tree, but the untrained, undisciplined girl had managed only a superficial scratch. Hostile intention had been signalled, and under international law, an IMBOD officer was permitted to retaliate. Cautiously, Astra glanced up.

The row of toes was still visible. So was the ball of the girl’s foot. Ha. Her assailant couldn’t go any higher. Maybe Astra couldn’t either, but if she was a Boundary constable now, charged with the sacred duty to defend Is-Land’s borders from criminals and infiltrators, one way or another she was going to win.

First, she needed to gather strength and take her bearings. Arm curled around the tree, she surveyed the terrain.

Her face was taking a direct hit of sun because, she saw now, for the first time ever she’d climbed above the forest canopy. Below her, a turbulent ocean charged down the steep mountain slope, pools of bright spring foliage swirling between the jagged waves of pine until – as if all the forest’s colours were crashing together on a distant shore – the tide plunged over the escarpment into a gash of charred black trunks and emerald new growth. The fire grounds were a slowly healing wound, a bristling reminder of Gaia’s pain. At the sight of them splayed out for acres beneath her, Astra’s breath snagged in her throat.

A Boundary constable couldn’t afford to contemplate the past; a Boundary constable had to live in the present, fully alive to its invisible threats. Astra shaded her eyes with her hand. Below the forest Is-Land’s rich interior shimmered out to the horizon, an endless, luxurious rolling plain. For a moment, Astra felt dizzy. From Or the steppes were either hidden by the trees or a distant vision beyond them; here they sprawled on and on like … she regained her focus … like the crazy quilt on Klor and Nimma’s bed, stuffed with a cloud-puff sky. Yes, the fields below her were like countless scraps of gold hempcloth, chocolate velvet, jade linen; fancy-dress remnants stitched together with sparkling rivers and canals and embroidered with clusters of homes and farms, the many communities that worked the steppes’ detoxified soil. She’d once asked Klor why the interior was called ‘the steppes’ – the gently sloping hills didn’t climb high, and the mountains were far more like stairs or ladders. ‘Ah, but these hills, fledgling,’ Klor had replied, ‘are stepping stones to a new future, not only for Is-Land, but the whole world.’ Now at last, as the steppes beckoned her into a vast lake of heat haze, she could see exactly what he meant. Klor also called the interior ‘Gaia’s granary’. The Pioneers had risked their lives to cleanse and replant Is-Land’s fertile fields and no true Gaian could gaze on them without a sense of awe and gratitude. The steppes, Astra realised, gripping tight to the tree, were a vision of abundance that made the firegrounds look like a tiny scratch on Gaia’s swollen belly.

But even the lowest-ranking IMBOD officer knew that the safety of Is-Land’s greatest treasure could never be taken for granted. Somewhere beyond the faint blue horizon was the Boundary, and pressed up behind it the squalid Southern Belt. There, despite decades of efforts to evict them, hundreds of thousands of Non-Landers still festered, scheming to overrun Is-Land and murder any Gaian who stood in their way. Nowhere was safe. Above Astra, higher in the mountains but only an hour’s trek away from Or, was the start of the off-limits woodlands, where the reintroduced megafauna lived, protected by the IMBOD constables who patrolled the Eastern Boundary. Twenty-five years ago, before the bears arrived, the off-limits woodlands had swarmed with infiltrators: cells of Non-Landers who had secretly journeyed from the Southern Belt, swinging out into the desert then up into the mountains where the Boundary was less strongly defended. Shockingly, they had succeeded in penetrating Is-Land, establishing hideouts in the dry forest from where they’d made surprise attacks on New Bangor, Vanapur and Cedaria, and even as far as Sippur in the steppes. IMBOD had fought back, jailing or evicting the infiltrators, blocking their tunnels and increasing the Eastern constabulary. When the dry forest was safe again, Gaians had established more communities in the bioregion: Or had been founded then, to show the Non-Landers that we weren’t afraid of them, Klor and Nimma said. But there hadn’t been an attack from the East for nearly two decades now and many Or-adults seemed to have forgotten the need for evergreen vigilance. That negligence, Astra feared, would be Or’s downfall.

She twisted on her branch, hoping to inspect Or, nestled between the flanks of the mountains. But her community was hidden by the trees. The forest, though, was no protection from infiltrators. Every Or building and every inhabitant was vulnerable to attack. Really, there ought to be an IMBOD squad patrolling these woods. After Astra got her Security shot and was super-fit and super-smart she was going to come up here every day and keep watch. Maybe, because it was her idea, she could organise the other Or-kids to help her. Meem and Yoki would do what they were told; Peat and Torrent wouldn’t like taking orders from an under-ten, but once she’d proved the infiltrator existed they’d have to listen. So now she had to do just that. Like Hokma and Klor proved things: with hard evidence.

Slowly, keeping her arm close to her body, Astra reached down to her hip and fumbled in the side pocket of her hydropac. Tabby’s creamy Ultraflex surface responded to her touch with a short buzzy purr.

‘Astra! Come down.’ Hokma’s voice tore up the tree like a wildcat. She must have pinpointed Tabby’s location. But this would only take a moment.

Astra carefully withdrew Tabby, activated his camera and slid him up her chest. She was going to frame the infiltrator’s foot and then show Hokma the proof. Hokma would phone Klor and stand guard beneath the tree with her until he came with reinforcements – maybe even an IMBOD officer. The girl couldn’t sleep in the tree, after all. When she finally came down, the officer would arrest her and take her back to Non-Land. She’d hiss and spit at Astra as they bundled her into the solar van, but there’d be nothing she could do. Then tomorrow, right before Astra’s Security shot, Astra would sync Tabby to the class projector and tell everyone the story of how she’d captured the last remaining Non-Lander in Is-Land. Everyone would gasp and stand and clap, even the IMBOD officers. She might even get an Is-child Medal.

The sun was boring into her temple. A bead of sweat was tickling the tip of her nose. Astra cautiously angled Tabby towards the clutch of grimy toes.

Click.

CRACK.

Noooooooo.

Another pine cone, drone-missiling down from the top of the tree, struck Tabby dead centre on the screen. Two hundred and twenty Stones’ worth of IMBOD-Coded, emoti-loaded Ultraflex comm-tech flipped out of Astra’s hand and twirled down through the branches of a sixty-foot pine tree to the distant forest floor. As she watched him disappear, Astra’s blood freeze-dried in her veins.

‘Astra Ordott.’ Hokma’s shout had ratcheted up a notch. ‘Get. Down. Now.’

That was Hokma’s final-warning voice. Things didn’t go well for the Or-child who ignored it. And more importantly, Tabby was wounded. He’d come under enemy fire, had taken a long, whirling nosedive to an uncertain, tree-scratched, earth-whacked fate. It was now Astra’s First Duty of Care to find him. Boundary constables swore to always look after each other, even if it meant letting a Non-Lander get away.

‘Coming,’ Astra called. Above her, what sounded suspiciously like a titter filtered through the pine needles. Agile as the lemur she’d studied that morning in Biodiversity class, Astra scramble-swung down the tree.

* * *

‘That Tablette had better still be working.’ Hokma’s stout boots were solidly planted in the soil, one hand was knuckled on her hydro-hipbelt, the other gripped her carved cedar staff, and above her red velvet eyepatch her right eyebrow was raised in a stern arc. This was her look of maximum authority. Hokma was tall and broad-shouldered, with full, imposing breasts and large brown nipples, and she could transform in a second from firm but fair Shared Shelter mother to unignorable Commanding Officer. Even her hair was mighty when she told you off, its dark waves lifting like a turbulent sea around her face. Right now, she was jutting her jaw at a patch of wild garlic: Tabby, Astra saw with a heart leap, had landed among the lush green leaves.

She ducked and with every cell in her body sizzling and foaming, recceing right, left and overhead in case of further sniper fire, she ran low to the ground towards Tabby. Belly first, she slid into a cloud of savoury stench and scooped her fallen comrade from his bed of stems and soil.

Oh no. His screen was scratched and black with shock. He must have suffered terribly, falling through the branches.

‘Stay with us, Tabby!’ she urged. ‘Stay with us.’ Turning her back to the pine tree to cover the wounded constable from further attack, she wiped him clean of dirt. Her fingertip moist with alarm, she pressed his Wake Up button.

Praise Gaia. The screen lit up and the IMBOD Shield shone forth in its bright insignia of green and red and gold. Twining one leg around the other, she waited for Tabby’s Facepage to upload. At last Tabby’s furry head appeared.

‘He’s alive!’ Astra jumped to her feet and punched the air. But Tabby’s emotional weather report was Not Good. His whiskery mouth was pinched in a tight, puckered circle; his eyes were unfocused; his ears were ragged and drooping. As she stroked his pink nose a thundercloud, bloated with rain and spiky with lightning bolts, bloomed above his head.

Tabby blinked twice. ‘Where am I?’ he bleated.

He wasn’t his normal jaunty self, but at least his vital functions were intact. She smooched his sweet face and clasped his slim form to her chest. ‘Don’t worry, Tabby. You’re safe with me. Everything’s going to be okay.’

‘Give.’ Hokma was towering over her.

Astra reluctantly relinquished Tabby for inspection by a senior officer and fixed her attention on Hokma’s navel. The deep indent was like a rabbit’s burrow in her Shelter mother’s creased olive-skinned stomach. Peat and Meem’s Birth-Code mother, Honey, sometimes let Astra stick her finger in her own chocolate-dark belly button, but it was impossible to imagine Hokma doing that. Hokma sometimes let Astra hold her hand, or briefly put her arm around her, but she never tickled Astra, or invited her to sit in her lap. Hokma ‘showed her love in other ways’, Nimma said. Far too often, though, Hokma’s love seemed to consist of telling Astra off.

Hokma unfolded Tabby from handheld to notepad mode. The Ultraflex screen locked into shape, but Astra could see that the image hadn’t expanded to fill it. Hokma tapped and stroked the screen all over, but nothing worked – even when she tried in laptop mode, his poor confused face remained tiny in the corner of the screen. ‘His circuitry is damaged.’ She refolded Tabby, handed him back and scanned Astra from toe to top. ‘Why aren’t you wearing your flap-hat?’

Her flap-hat? This was no time to be worrying about flap-hats. ‘I was in the shade,’ Astra protested, gripping Tabby to her heart.

‘Oh?’ Hokma gazed pointedly around at the shafts of sunlight slicing through the pines. But she let it go. ‘It doesn’t matter where you are outside, Astra. You have to wear your flap-hat until dusk. Do you even have it with you?’

‘Yes,’ Astra muttered, unzipping her hydropac back pocket. Flap-hats were for babies. She couldn’t wait until she was eight and her skin was thick enough to go out without one.

She put the stupid thing on, but Hokma wasn’t satisfied yet. ‘And what in Gaia’s name were you doing climbing trees? I told you to meet me at West Gate at four.’

‘You are ten minutes late to meet Hokma at West Gate,’ Tabby piped up helpfully. ‘You are ten minutes Hokma late to meet West Gate at four. You are ten Hokma West to late minutes …’

‘He’s got shell-shock!’ Astra cried.

‘I said he’s damaged. Turn him off.’

‘No! He has to stay awake or we might lose him.’

‘All right. Put him on silent then.’

Astra obeyed and slipped Tabby back into his pocket. ‘Klor can fix him,’ she offered, scuffing the ground with her sandal. ‘Like he did last time.’

‘Astra. Look at me.’

Constable Ordott straightened up and obeyed her Chief Inspector’s order. This could be big-trouble time.

But fire wasn’t flashing from Hokma’s hazel-gold eye. Her brows weren’t scrunched together, forcing that fierce eagle line between them to rise, splitting her forehead like it did when Or-kids neglected their chores or fought over biscuits that were all exactly the same size, as Hokma had once famously proved with an electronic scale. Instead, her square face with its prominent bones was set in a familiar, patient expression. She looked like she did when explaining why a certain Or-child rule was different for under-tens and over-nines. And when Hokma was in explaining mode, you could usually try to reason with her. She always won, of course, but she liked to give you the chance to defend yourself, if only to thoroughly demonstrate exactly why you were wrong and she was right.

‘Klor’s got better things to do than mending your Tablette every two weeks, hasn’t he?’

Hokma’s tone was calm, so Astra risked a minor contradiction. ‘Klor said it was a good teaching task,’ she attempted. ‘He showed me Tabby’s nanochip. I learned a lot, Hokma!’

‘You take Tech Repair next term. Tablettes are expensive. You should never play with them while you’re climbing trees.’

‘But I was looking for the girl. I needed Tabby to take photos.’

The ghost of a frown floated over Hokma’s features. ‘What girl?’

Astra whipped Tabby out again. Maybe he couldn’t talk properly, but he could still see. She clicked his camera icon and speed-browsed her photos. Hokma was getting dangerously close to impatience now, but in a minute she would be praising Astra and Tabby for their valour and initiative; she would be calling Or to raise the alarm and gather a team to bring the enemy down.

‘The girl in the tree. Look.’

But the photo was just a muddy blur of greens and browns.

‘I don’t have time for these games, Astra.’

Astra stuffed Tabby back in his pocket. No one would believe her now. ‘It was the girl I saw last week,’ she muttered. ‘The one who lives in the forest. She’s a Non-Lander. An infiltrator. She threw pine cones at me. See.’ She held out her bruised hand. ‘So I dropped Tabby, and the photo didn’t turn out.’

Now it deepened: the warning line between Hokma’s eyebrows. Silently, she examined Astra’s knuckles. When she spoke again, it was as if she were talking to somebody young or naughty or slow: to Meem or Yoki.

‘There’s no girl living in the forest, Astra. You’ve just scraped yourself again.’

‘But I saw—’

Hokma bent down and grasped Astra’s shoulders. Astra was supposed to look her in the eye, she knew, but she didn’t want to. She stared down at her feet again and dug her sandal toes into the garlic patch. Torrent was going to tell her she smelled like an alt-beef casserole when she got back to Or.

‘There are no Non-Landers in Is-Land any more,’ Hokma said, using her instructor voice as if Astra was stupid, as if Astra hadn’t just completed Year Two Inglish Vocabulary a whole three months ahead of her class.

She folded her arms and glowered up at Hokma. ‘Klor and Nimma said there are still lots of infiltrators in Is-Land,’ she retorted. ‘They’re disguised as Gaians with fake papers or they’re still hiding in the off-limits woodlands.’

Sometimes when her face was this close to Hokma’s, she felt an urge to stroke her eyepatch, especially the velvet ones. Nimma made them using material from a hoard of ancient curtains she used only for very special things, like the crazy quilt, or toy mice for toddlers, or fancy purses for the older girls when they started going to dances in New Bangor. Right now, however, Hokma was gripping her shoulders tighter until they hurt. Just as Astra was about to squeal ow, her Shared Shelter mother let go.

‘Klor and Nimma shouldn’t be scaring you with their rainwarped notions, Astra,’ she said firmly. ‘The off-limits woodlands are heavily patrolled, and if IMBOD didn’t catch any infiltrators, the reintroduced bears would.’

Usually Astra loved to hear Hokma swear, but right now it was infuriating to be argued with. To be punished for caring about national security. How could Hokma refuse to acknowledge the ever-present dangers they all lived with? She was supposed to be smart.

‘No,’ she insisted, rubbing her shoulder, ‘the Non-Landers have changed tactics. They deliberately aren’t attacking us now. They live up high in tree nests, where the bears can’t climb. They’ve got stolen Tablettes that can hack IMBOD emails and they’re stockpiling bows and arrows through the tunnels and helping Asfar and the Southern Belt prepare to attack us when the global ceasefire finishes.’

‘What on Gaia’s good earth have they been telling you?’ Hokma snorted. ‘Klor and Nimma just aren’t used to living in peace, Astra. The tunnels are all blocked up, and Asfar is our ally.’

‘There are new tunnels. And Klor said the Asfarian billionaires could—’

‘Enough, Astra. There’s no such thing as a Non-Lander girl running wild in the woods. Everyone in Is-Land is registered and has a home. If you saw someone, she’s from New Bangor and her parents are close by.’

‘No.’ Astra stamped her foot. ‘She was dirty and her hydropac was really old. She lives here. She—’

‘I said FOG FRIGGING ENOUGH,’ Hokma bellowed.

Astra stepped back, her heart thumping in her chest. Nimma and Klor never yelled like that, out of nowhere, let alone swore at her. When Nimma was angry she talked at you rapidly in a high, sharp voice, whittling you away with her rules and explanations, and behind her Klor stood solemn and sad, shaking his head and saying, ‘Nimma’s right, Astra,’ so you felt you had terribly disappointed him and eventually, half-ashamedly, accepted your punishment. This furnace blast of fury was very different. She stood quivering, not knowing what to do.

Hokma waved her hand through the air as if to brush away a bothersome insect. ‘Astra, I’m sorry I shouted. I didn’t come here to bicker with you. I asked you to meet me so we could discuss something important. Let’s leave this discussion behind us. Now.’

Astra kicked at a stone. Okay, Hokma had said she was sorry – but she didn’t sound sorry. She was being unfair and bossy and ignoring invaluable ground evidence. That was senior officers all over. Most of them, it was well known, had long forgotten what it was like to be out there, vulnerable and under fire from hostile criminals.

Hokma turned and started down the trail back to Or, swinging her staff by her side. ‘Don’t you want to see Wise House?’ she called over her shoulder. ‘If there’s time before supper chores you can help me feed the Owleon chicks.’

Astra stared down the path, her heart bobbing like a balloon in a sudden gust of wind. Wise House? Where Hokma lived alone breeding and training the Owleons, and no one was ever allowed to visit? Hokma was inviting her there to feed the chicks? Yes way.

She sprang forward to catch up. A pine cone zinged over her head and hit the dirt path in front of her feet. She wheeled round and craned up at the jack pine. The top branches were waving gently but the Non-Lander girl was invisible, camouflaged by a screen of needles and adult indifference.

‘We’ll prove it one day, Constable Tabby,’ she swore. ‘After I get my Security shot.’

‘Astra.’ Hokma was nearly at the brook now. Astra glared at the top of the tree and stuck out her tongue. Then she spun on her heel and raced after Hokma.

‘Wait up,’ she shouted. ‘Wait for me!’

Astra jumped into Hokma’s footprints then skipped through the pines after her Shelter mother. She was going to Wise House, to Wise House, where no one except Hokma, Ahn and IMBOD officers were allowed to go. The officers came twice a year, to inspect the Owleons and take the fully grown and trained birds away. Since Astra had started school she hadn’t seen them arrive or leave, but every few weeks she spied Ahn in his canvas-topped boots and old straw hat, his Tablette tucked in a scroll beneath his arm, striding out towards West Gate of an evening. He and Hokma were Gaia-bonded, Nimma said, a bond of more than twenty years, though it was hard to believe because they never even sat together in Core House at mealtimes, let alone held hands or kissed like Klor and Nimma did. Still, Nimma said that some people liked to kiss each other when no one else was watching.

Ahn’s lips were so thin they were nearly invisible, but still it was just conceivable that Hokma might want to kiss them and give him permission to visit Wise House; what was nearly impossible to accept, however, was that Or-kids – even her, Hokma’s own Shelter daughter – were strictly forbidden. Or-kids were noisy and galumphing, Hokma said, and ran around and frightened the birds. ‘I’m not galumphing,’ Astra had complained to her last year. It wasn’t fair. Hokma was her Shared Shelter mother so why couldn’t Astra visit her? Peat and Meem went to stay with their Birth-Code-Shelter parents sometimes, and Yoki often stayed with his Birth-Code uncle. In fact, all the other Or-kids except her got to stay with all their Shared Shelter parents. Especially considering that she didn’t have a Birth-Code mother or a Code father, it wasn’t right that she should be stuck with Klor and Nimma all the time.

‘You’re the biggest galumpher of the lot, Astra,’ Hokma had laughed. ‘You’re always knocking into people. Better save all that energy for the Kinbat track for now.’

It wasn’t true. She could run fast, and sometimes her elbows jabbed into adults who didn’t get out of the way. But she was light, and she knew she could be a silent tracker in the woods if she tried, even with her sandals on. But when she’d tried to explain, Hokma had got cross, and told her to stop arguing or she’d be running extra laps for the next two weeks.

I wish you weren’t my Shelter mother, Astra had nearly shouted. But what if Hokma had said, Fine, I’ll stop now? So instead Astra had stormed off to the orchard, where she’d sat under a fig tree nestling the hurt like a dead bee in a puff of cotton. Later, she’d carefully placed the bee-hurt in a little drawer inside her heart. She didn’t like to open the drawer very often, though, because even though the bee-hurt was dead, it could still sting her.

But now, at last, she was going to visit Wise House. As Astra followed Hokma down to the brook, the drawer in her heart flew open and like a small miracle, the bee took flight.

* * *

Ahead of her, Hokma crossed the small wooden bridge Klor and Ahn had built twenty years ago, when Or was new and the brook little more than a dried-up ditch. The water was deep again now, a smooth umber current nearly as deep as Astra was tall. She bent down, ripped open her Velcro sandal straps and, arm back behind her head like she’d been taught in cricket practice, hurled her shoes across to the opposite bank. The second one landed short of the first and rolled dangerously down towards the water.

‘Astra!’ Hokma’s hands were on her hipbelt again. But the sandal didn’t fall in. Hurriedly, before Hokma could object, Astra slipped off her hydropac and slung it across the brook too. As the pac sailed past Hokma’s head and into the woods, she splashed into the water. Clothed in its silky flow, she swam to the other side, dipping her head beneath the tarnished green reflections of the trees to refresh her hot face. Clean and glistening, she scrambled up the bank.

‘Better?’ Hokma watched Astra put her sandals back on. Leaves and bits of bark had stuck to her wet feet, but they would soon dry. Hokma tugged her flap-hat back down on her head and Astra lunged up to the path. On this side of the bridge it rambled through a bower of ancient oaks, rare trees that had somehow survived the Dark Time and become a place of solemn pilgrimage for every international visitor to Or. Today Astra and Hokma had the bower to themselves. As Astra pranced through the shady glade, the drops of water sparkling on her skin were consumed by the familiar sheen of sweat. She slowed down and let Hokma catch up with her; now they walked side by side, Hokma marking their strides with her staff, her free hand swinging lightly beside Astra. Quietly, carefully, almost as if she herself didn’t know what it was doing, Astra’s hand reached up and curled around two of Hokma’s fingers. Hokma squeezed. Astra gripped a little tighter.

‘Hokma?’

‘Yes, Astra?’

‘What does bicker mean?’

‘To have a nonsense argument. An argument no one can win.’

‘Oh. I thought it did, but I wanted to make sure.’ Somewhere, a wood pigeon mournfully echoed its own coo. Astra giggled. ‘It sounds like what the birds do outside my window. Bicker.’

Hokma gave a gruff laugh. ‘Birds bicker. Squirrels squabble.’

Astra thought for a moment. ‘And crows crorrel, I mean choral. I mean quarrel. Hey, I invented a tongue-twister! Yay.’ She risked a skip. Just a little one, so as not to pull too hard on Hokma’s arm and make her let go.

‘You certainly did.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...