- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

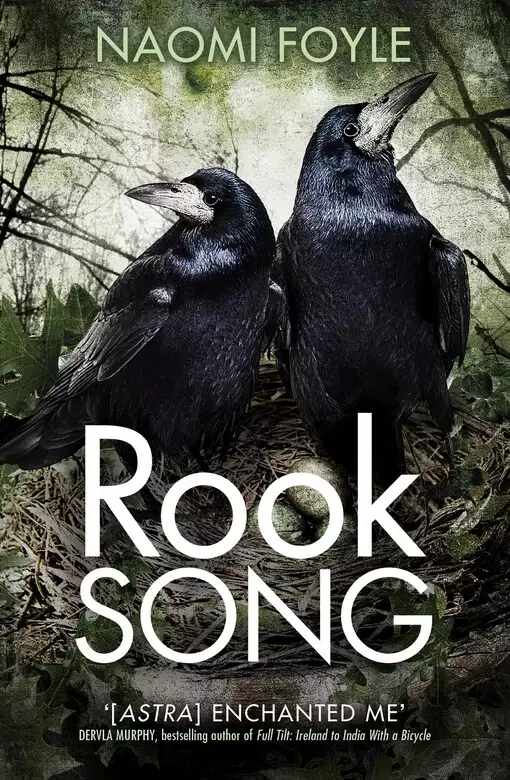

Synopsis

Astra Ordott is in exile. Evicted from Is-Land for a crime she cannot regret. Recovering from a disorienting course of Memory Pacification Treatment, Astra struggles to focus on her goals - to find her Code father and avenge the death of her Shelter mother. But the deeper Astra ventures into this new world, the more she realises her true quest may be to find herself.

Release date: February 5, 2015

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 496

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Rook Song

Naomi Foyle

The Council of New Continents (CONC)

Non-Lander CONC Employees

The Youth Action Collective (YAC)

The Non-Land Alliance (N-LA)

Nagu Three [In Kadingir]

Pithar [In Zabaria]

Is-Land Ministry of Border Defence (IMBOD)

Is-Land

Astra

‘Ack-ka-ka-ka-ckak!’

Astra tipped her sack of dirty laundry into the pool, gripped her paddle and began to stir. Beside her, Uttu bent and plucked a small gown from the suds. It was a baby’s garment, blotched with sulphurous and rust-red stains. Protesting in her guttural tongue, the tiny elderwoman thrust the dress out to the other washers like a piece of vital evidence in a crime.

No. Please, no. Desperation mounting in her chest, Astra focused on a pillowcase, fixed her gaze on its thinning weave and frayed seams. But it was no use – the grey wave was rising again, flooding her skull, dredging up an image that blotted out the room: a young girl’s limp body, her white hipskirt drenched with blood.

Sheba was dead. Sheba had been killed by a bus-bomb. And as always, the wave broke the news as if for the first time. Staggering under the rush and crash of fresh grief, she resisted the only way she knew how.

I’m working. I’m working. I’m working.

Her jaw rigid, the paddle handle digging into her chest, she repeated the silent mantra. With a nauseating suck, the wave withdrew. The voices faded, the image of Sheba melted away, the laundry pool and its three robed washerwomen swam back into focus. But the sickness lingered: numb limbs, a sour lump in her stomach, the thick familiar mist stealing back into her head. There was never a full recovery from the grey wave. Since the Barracks, she had either been fighting it off, or submerged in the dank threat of its return.

No one seemed to have noticed her near-collapse. Around the pool, palms pressed to hearts, the three washers had launched into a round of lament. Beneath her cap of salt and pepper hair, Uttu’s withered face was wrenched open in a long, imploring cry. Tall, bone-thin Azarakhsh keened as if to pierce the whitewashed stone vaults, white strands escaping her loose bun like wisps of static electricity. Loudest and deepest was Hamta. Her gauzy blue headscarf shimmering in the light from the high arched windows, the mountainous woman raised her arm and with a swift chopping motion released a resounding ‘Hai!’

‘Hai! Hai!’ the others echoed, their anger igniting a thin ray of resentment in Astra’s clouded head. Sheba had been six when she died, years before Astra was even born. Of course she cared about her Shelter sister’s death, but why had an infant’s dress triggered such an overwhelming reaction?

But anger had no chance against the fog. The brief beam of indignation dulled and the dismal mist closed in again, bearing its cold, lightless truths. Of course she would suffer for Sheba: that was what IMBOD had engineered the grey wave to do – fling all her losses up from the deep, every last one, bloody and raw as gutted fish.

A gleam caught her eye, luring her back from the brink of despair. The charms on Uttu’s copper neck chain: the washerwoman’s gold ring and miniature weaver’s shuttle, dangling over the water as she plunged the baby’s dress back into the pool. She watched the garment sink into the mottled sea of fabric. It was hardly unique. Once a week the washers cleaned CONC uniforms, otherwise the laundry came from the Treatment Wards scattered over the Southern Belt, virtually all of it soiled with some lurid combination of blood, pus, faeces and vomit. Her job was to clean it.

She began shunting the linens back and forth over the tiles, stirring the day’s broth of soap and human crud, working to the rhythm of the crones. On her first day in the laundry she’d grimly pounded, thumped and flipped the cottons, splashing and puddling the uneven stone floor. The other washers had hissed and shaken their fingers. In their thin rubber sandals, it was easy to slip, Uttu had mimed. The shrunken elderwoman had tapped her own pointy elbow and pulled a face. Ouch. Then she’d laughed and patted Astra’s arm. She’d flinched, pulled away, but had watched Uttu carefully after that, copying her movements throughout the washers’ various tasks.

After two weeks in the laundry, she was practically a crone herself. Her hands, bleached by the window light shafting over her shoulders, looked as ancient as Uttu’s, the skin wizened and chapped from scrubbing and wringing gussets, armpits, bibs – anywhere on a garment the body’s fluids could splatter or seep. She didn’t care. Uttu had offered her a pair of gloves, but she’d sweated inside the yellow rubber and the bar of soap had constantly slipped from her fingers, incurring first the raucous laughter of the others, and then grumbles. So now she worked bare-knuckled like them, slapping on the coconut moisturiser provided in tubs by the door at the end of her shifts; the thin white grease absorbed into her skin without trace, just as the washers’ occasional stabs at communication failed to penetrate her fog. She could understand their basic commands – her eleven years of Inglish and Asfarian lessons occupied some part of her mind IMBOD couldn’t – or hadn’t bothered to – hijack. But between them the three old women had only a smattering of the two official CONC languages. ‘So-mar-ian,’ Uttu had said proudly on the first day, patting her bony chest; as if oblivious to Astra’s incomprehension the little woman often cackled at her in the Non-Land tongue, but otherwise the washers addressed her mainly to issue instructions or chuckle at her blunders.

That was fine. She wasn’t allowed to talk about why she was here, and she didn’t want to talk about what was wrong with her. No one in the CONC compound would believe her if she told them what had happened at the Barracks, and even if they did, no one would be able to fix her. She was damaged goods, a leaking contagion: dumped in the small dark hours at the back entrance to this crumbling fortress, she’d been passed round like a sack of rotting potatoes from the night porter to the day receptionist to the Head of Staff and now, yet again, confined where she could do least harm. The Head, a shrewd man with a trim black moustache, had briskly assessed her wasted arms, dull skin and shadowed eyes and offered her a doctor’s appointment. She’d refused – she’d rather be buried alive in a termites’ nest than see another doctor – and he’d shrugged, scanned his screendesk and neatly slid her deficiencies into a hole in his rota. Working in the laundry would be good for her muscles, he’d said. The Compound Director would meet with her soon to discuss her family situation. In the meantime, he’d instructed, peering at her over his small round glasses, she was to remember that her Code status was strictly classified information.

So far no summons had come. Of course not. No one in this arid work camp gave a flying frig about her or her Code father. And anyway, given what happened to her whenever she thought about Zizi Kataru, she wasn’t sure she’d make it through that conversation alive. Just the flicker of a thought about him in the Head of Staff’s office had been agony enough.

No, she didn’t need the Director’s help. She would make her own plans; she would hide in the compound, working as a local employee of the Council of New Continents, until she’d figured out what to do. Silent, invisible, swathed in these shapeless robes, she was almost safe.

Beside her, Uttu poked at a pillowcase, chattered to Hamta. Astra picked up her pace. She was slick with sweat now, the robes clinging to her flesh. She wanted to tear off the heavy, damp fabric, but that was impossible. She had a right to her spiritual practices, the Head had said, but going sky-clad would alienate the Non-Landers in the compound and – he had paused before adding – ‘almost certainly attract unwanted attention’ from some of the internationals. She had understood. With her shaved head and neurohospice scar, she already attracted plenty of unwanted attention in the corridors and dining hall. So she had taken the two robes he’d offered, soft white with blue trim, glad at least to discard the rough hemp sheet IMBOD had bundled her up in after the Barracks.

She worked steadily on, her nose prickling. At least the ammonia masked the stink of shit; the first soak, mostly composed of soiled sheets and nappies, was a cesspit. Careful not to splash, she dug at the laundry with her paddle, separating folds to dissolve any solids lurking in the creases. The work was getting easier. She no longer felt disgusted by the morning soak. And she could stand up for the whole day now, needing just the normal scheduled breaks. Soon, during the second soak, they would go out to the courtyard colonnades for coconut water, prayers and yoga. As the ammonia ate into the bloodstains, Hamta would sit on a mat with her eyes closed, performing elaborate chants and prostrations, and Azarakhsh, after her own private prayers, would lead Uttu and Astra in sun salutations – the only time Uttu, a supple cocoon in her white robes, was silent all day.

After the break they would re-rinse and wring and peg the laundry out to dry in the courtyard. There were electric dryers, a wall of them in the next room, but these, Uttu had instructed in her rudimentary Asfarian, were only for use when it rained. Appliances had to be imported from Asfar, Astra had finally understood; they were difficult to repair or replace. That was the way it was here: water, solar power, fruit – nearly everything was rationed in the compound.

Whatever the weather, after lunch the washers took another prayer break followed by siesta. In the afternoon they ironed and folded and repacked yesterday’s laundry in the bags for the CONC medics to pick up. Finally, they brought in the dry load. The clean linens from the courtyard smelled of sunshine, and wielding the heavy iron felt powerful, but Astra’s favourite task was wringing. She positively looked forward to wringing. The skin on her hands could fall off in shreds as long as she could keep gripping and twisting fibres tender as flesh, seams tough as gristle. One day, she thought, prodding viciously at a sheet, she would wring Ahn’s scrawny neck until it snapped.

CRACK. She had risked it, and here it came: a sharp warning shot. Not the grey wave but the pain-ball. The hard metal marble that shot up from her cranium scar-hole whenever she thought about anyone IMBOD didn’t want her to remember: her Code father or Hokma, Ahn, Dr Blesserson, or any of the doctors and Barracks officers who had ruined her life. She leaned on her paddle and took the dazzling hit to her left temple. It was worth it. But she had to be careful. She had learned to her cost that, if she persisted too long in dreams of revenge, the pain-ball would tear a trail of white fire around her skull, detonating a series of phosphorous explosions that would bleach her brain, leave her blind and moaning back on the floor of the Barracks.

I’m working. I’m working. I’m working.

The mantra worked. The pain-ball rolled back into its socket. She inhaled, placed her foot on the rim of the pool and reached across to snag a floating nappy with her paddle. Like an electrical current, a ripping sensation sizzled through the triangle IMBOD had cross-hatched on her perineum.

The cloud of misery returned and tears sprang to her eyes. These relentless attacks – the pain-ball, the grey wave, the buzzing nest of her brand-wound, as if the nerves were permanently singed, flaring up at night and keeping sleep at bay for hours. An ill wind in her head hissed all this was her own fault . . . and for a weak, terrible, bottomless moment she didn’t know if she could stand it any more.

‘Astra?’ Uttu was touching her arm, her curious hazel eyes asking, What’s wrong? Astra ducked the woman’s gaze, pulled away, dragged the nappy towards her. No. Until she fell unconscious, face down in the pool, she would bear it. She had learned the tricks to quell the wave and stop the pain-ball and she would conquer the stinging brand-wound too. It was an irritant, like the ammonia. That was all.

She scraped at a soggy crust of shit on the nappy. A warm breeze wafted in from the open door to the courtyard, followed by the hectic pattering of feet and a shrill fusillade of giggles. She didn’t bother to look round. Beset with glee, the three children would be clinging to the door frame, pointing at her skull-hole and speculating in fierce whispers as to its cause. They were children of other local workers, speaking a Non-Landish tongue, but the language of widened eyes, wagging fingers and bossy tones was universal. The older girl was clearly the ringleader; she would be firmly overruling her brother’s interjections while their plump little sister stared up at Astra, dumbfounded.

‘Hai!’ Uttu turned and flapped the children away. The kids thundered back out into the courtyard and the old woman addressed Astra rapidly again. She was smiling, her gleaming gold charms a warm wink in the sterile vault of the room. Across the pool, Hamta paused from paddling and smoothed a strand of black hair back into her voluminous headscarf.

‘She say, “They like you”,’ the large woman announced proudly in Asfarian. Uttu clapped delightedly and Azarakhsh’s long face creased up in a gap-toothed grin, both clearly impressed by Hamta’s triumphant sentence-making.

Astra jabbed a wodge of pillowcases with her paddle. Like her? The kids were frigging addicted to her. They followed her around the compound, pointing at her head, hiding behind corners in chattering huddles as if betting on what she would do next, though there was nothing she could do except wait for her hair to grow back. Much as she wanted to pass without notice, she couldn’t cover her skull like Hamta: headscarves were Abrahamite garb.

The pool water was a grim khaki sludge and the suds had deflated to pancake-flat clouds, drifting over the continents of fabric. Uttu pulled the plug. The filthy water gurgled through the pipes to the algae-scrubber, to be cleaned and returned in an endless cycle of conservation; the laundry water was probably as old as the crones. When the pool had drained Hamta took a hose from the wall and aimed a jet of cleaned water over the laundry. As Azarakhsh slopped the wet fabric around in the spray, Uttu leaned over the pool and retrieved the baby gown. Astra’s cranium throbbed, but that was all: the wave trigger appeared to have exhausted itself for the moment. Muttering to herself, Uttu smoothed out the little dress on the rim of the pool. Then she carefully laid the garment back on the rising surface of the water, dug a scoop into the bag of powder by the hose, and sprinkled detergent over the stained frills.

Astra’s nose twitched. She thrust her hand into her robe pocket – pockets were the only point of clothes – and pulled out her hanky.

Huh-huh-huh-TSCHOO.

‘Amon,’ Azarakhsh responded, drawing an Ankh on her chest, as she did before and after yoga.

‘Amon-nia,’ Hamta guffawed, setting in motion a circle of translation and laughter. Astra wiped her nose and stuffed the hanky back in her pocket.

‘Bless ooh,’ Uttu announced loudly.

Blesserson?

She was practically knocked sideways by the blow: a cannoning skull-ball smashing her vision into a field of white stars.

As if from the other side of the galaxy, across the pool Hamta quizzically echoed the phrase. ‘Bleh sou?’

‘Inglish,’ Uttu’s voice came floating to her. ‘Bless. Ooh.’

Inglish. She seized the word like a life ring in the void. This wasn’t a memory, just information. It shouldn’t hurt. Against the comet trail of pain, she kicked out for the mothership of facts. To bless, yes, she knew that verb, it meant to make holy. ‘Bless you’ could be used to say thank you or, when someone sneezed, to deter evil spirits. Evil beings like Dr Samrod Blesserson – CRACK: a bright white supernova of pain as the ball hit her temple, but she didn’t care. She had to finish the thought, finish the job. One day she was going to break Dr Blesserson, break Ahn Orson, shatter their thin crooked smiles, hammer their cold glass hearts into dust.

Right now, though, she had to stop this fanatical assault on her head. She forced her eyes open, focused on the pool, her lips moving with the mantra.

I’m working. I’m working. I’m working.

Her eyes blazed with tears. But the pain-ball receded. The white stars dimmed. The laundry room reappeared. She inhaled and stood still, hardly daring to believe in this temporary reprieve.

Beside her, Uttu was stirring again, head down, bangles tinkling as she briskly frothed up the water. Hamta and Azarakhsh, though, were both looking, frowning, at Astra. Why? Were they waiting for her to speak? To say what? Thank you? She couldn’t say anything. Her mouth was a desert, her throat a parched well. And now here it came, though she hadn’t been thinking about Klor or Sheba or Peat or anyone she loved and missed: the grey wave, crashing down with a thundering force.

There was no point in talking to these people – there was no point in talking to anyone – because she was a freak, like a warty carrot, or a red pepper with a double goitre – something you took photos of to laugh at. Why had the Head of Staff made her work with people? She should be shut away, locked up on her own. She was useless – worse than useless, a complete monstrosity. She was here in this prison, being eviscerated by her own body, because she was a grotesque, worthless, hideous botched job, a Code nightmare, a deformity who should have been destroyed at birth. She was paralysed by the enormity of it, every muscle in her body clenched hard as granite. She was a freak of nature and culture. Half Is-Lander, exposed as a pathetic fake Sec Gen, half Non-Lander, a criminal’s blood pumping through her veins. She would never belong anywhere. That’s why she was here, trapped in a stone warren with no trees or grass or flowers, a place where no birds sang, a prison of pain and humiliation where everyone laughed and stared at her and even her Gaia garden hurt. She ought to implode, right now. She should put herself and everyone else out of her misery. She should drink a jugful of ammonia, hang herself with a pus-stained sheet, throw herself from the ramparts, smash her head open on the courtyard floor.

The wave parted. Around her, as if behind a gauze screen, the washers were exchanging glances; Uttu, head cocked, was peering up at her with concern. But they didn’t matter. What mattered was the sunlight playing over the soap suds and fabric. The pool looked like a brain, she realised. A round grey slice of wrinkled brain, soaking in foamy bubbles. A button on a bed shirt glinted up at her like a dare.

‘Excuse me,’ she said in Asfarian, laying her paddle against the rim of the pool. ‘I am just going outside for a short break.’

Peat

‘Aiiiiiii. Aiiiiiii. AIIIIIIIIIIIIII.’

Limp, feebly scuffling, the sheep was a silent protester, but Jade was screaming as if the knife were held to her own mother’s throat. His Sec sister felt the animal’s pain; Peat was still wrestling with disbelief. Was he really watching this? A short wiry man gripping the front legs of a struggling black ewe, his burly collaborator squeezing the creature’s jaw shut, pressing a long curved blade to her neck. These were butchers. To screen such images was illegal.

But he wasn’t in Is-Land. He was in the Non-Land Barracks now, and this morning at the training field welcome lecture Odinson had told them all to expect to be tested. Above him, the men began chatting in a tongue he didn’t understand, chatting and laughing and gloating. Like a slow bolt of lightning, jagged and hot, a shudder ran through him: a huddle shudder, shared by his entire division, one hundred Sec Gens standing in neat rows in a Non-Land Barracks hall, heads haloed, shoulders gleaming in the glow of the huge wallscreen where, still chuckling, the bulky man was raising his arm, flashing the knife in front of the creature’s terrified eyes.

‘Noooooo,’ Jade shrieked in front of him.

‘NO!’ Robin bellowed to his left.

‘No!’ Laam echoed on his right. But nothing could stop them, these casual monsters intent on dragging shame down over the entire human race. The knife sawed into the black fleece. Blood rose in the gorge. A shocking red gash.

Jade was screaming herself hoarse. Incredulity was no longer an option. It was impossible not to feel something. For Peat, that was anger, rapidly building to the verge of explosion. He knew animal slaughter happened – he’d been told about it all his life, even read about it. And now he knew why you weren’t allowed to watch it. It was unbearable, the sight of a defenceless animal – that gentle, grazing, milk-giving, wool-offering ruminant, a creature that would work for you as long as it lived, needing nothing but grass and medical aid and a decent retirement package in return – that beautiful sheep, being killed without even an anaesthetic, kicking feebly as the butcher sawed on, the long knife tearing open the living throat as easily as Peat’s Shelter mother might rip up an old blanket.

Everyone was shouting now. ‘Murderers!’ he bellowed with them, his division’s distress pounding in his ears. ‘Meat-eaters.

Non-Landers.’

Then the pain hit. Tears seared his eyes, bolts of anguish shot through his stomach until he wanted to retch. He gasped, clutched his stomach. No. Stop. Please stop. He didn’t want this. To stand and watch two men bind a conscious creature, hack at its throat, without even an anaesthetic, joking as they did so. It was agony. Only the faint buzz in his chest, the heart connection with his Sec siblings, made it possible to endure the torment. The division formation was tightening now, warm bodies shrinking closer together, as up on the screen the butcher roughly tilted the struggling sheep, yanked back its head.

Blood spilled from the ewe’s neck, staining the earth – Gaia forced to taste of her own child’s murder. The tingling heart bond with his siblings, their velvet skinship, was not armour enough against this atrocity. He couldn’t watch any more. He couldn’t. His stomach was in shreds. His chest about to burst open. It was worse than his counselling sessions. Like being pierced, in one swift corkscrewing assault, by all the grief, fear and fury he’d battled week after week in Atourne. He gasped, shut his eyes, tried to banish the image, the dark pool of blood spreading through his mind.

‘Look, Sec Gens, look,’ Odinson urged through his earpiece. ‘I know it is hard, but you must look. You are not in Atourne any more. This is Non-Land. Beyond the Barracks walls you will see things you have never before confronted, the worst Old World depravities on parade. Here, animals are enslaved, starved, slaughtered, roasted, eaten. Young girls are forced into marriage with lustful old men. Alt-bodied people are left to beg on the street. You do not want to be shocked when you see these things. You do not want to be the weak fledgling in the flock. This is a test you must pass.’

His eyes were still shut. He gulped in the darkness. He was failing, letting everyone down. He had to obey: he had to look. He had learned, hadn’t he, how to cope with emotional pain. He had tried so hard to conceal a lifetime of pain, to manage it, to control it. Feel it, Peat, the counsellor had said, over and over again. Face it. Feel it. Ask for help when you need it. You don’t have to carry the burden alone.

He opened his eyes, grabbed Robin and Laam and forced his face to the screen. Hip to hip, arms twined around shoulders, the tight rows of his division obeyed their commander, watching as the footage of the butchers and their victim at last, mercifully, faded away.

‘Good, Sec Gens, good,’ Odinson crooned from his lectern at the edge of the screen. Through wet lashes, Peat drank in the sight of him: his iron-willed commander, his tall, proud anchor in this storm. ‘You must be prepared,’ the Chief Super urged, ‘for first the Non-Landers will slaughter a sheep and next they will slaughter your daughter.’

The test was not over. It was plunging into deeper places, turbulent depths Peat had once thought he knew the measure of, but was now learning were fathomless, overwhelming, beyond any logic or law to contain. To the noble strains of the Shield Hymn in his earpiece, the wallscreen filled with faces: familiar faces – faces he had grown up with, on Tablettes and bus shelter screenposters, plaques mounted beside fountains and memorials:

The youths from the bike shop in Atourne, juggling spanners, a row of racing trophies gleaming behind them on the wall.

The children from Hilton, square on square of grinning little kids, missing front teeth, hair neatly combed and oiled and braided for their school photos.

The family from the restaurant in Sippur, picnicking on the banks of the Shugurra River, their last ever holiday, the mother pregnant with the son who would never be born.

Jade was sobbing quietly, her tawny shoulders shaking in front of him. Beside him, Robin’s breath hacked the air. If air was entering or escaping his own lungs, Peat couldn’t feel it. He was numb, his whole body stiff with dread.

Laam reached up. His thumb rubbed reassuring circles on Peat’s nape: he knew that she would be next.

Sheba: the Shelter sister he had never known. A little girl blown up on a bus, before he was born, killed, like the others, to the rejoicing of Non-Landers. And here she was, her bonny baby-toothed smile filling the screen. The smile Nimma had dusted every week on the Earthship mantelpiece. The lightbulb smile that had burned a hole through his childhood.

His stomach knotted and his vision blurred. The bus-bomb that had killed Sheba had also claimed his Shelter father’s leg, broken his Shelter mother’s heart, riddled Peat with unspoken grief. How to explain it? He had tried, to the counsellor: We were never all together. Sheba was always missing. Sheba was never there. ‘And how did you cope?’ the counsellor had asked, her voice sliding back to him now. I don’t know. I studied law. I guess I thought I could get justice for her one day. Yes, he had studied law, only to discover two traitors in his own family: Hokma, who had separated Astra from her generation and secretly deformed her mind, and Astra herself. Astra, who had never been there – had never been who they all thought she was.

His chest heaved. He’d been doing so well at forgetting her but now his emotions were churned up, the Sheba sorrow released, it was impossible not to think about Astra. He stared at the screen through his tears, tried to soak up the sunshine of that little girl’s smile, but like a hammer to the heart it hit him again: Astra had never cared about him. She had almost destroyed him. Astra, loyal to a traitor, contemptuous of the Sec Gens – of her own Shelter siblings – had nearly cost Peat his own destiny, the full glory of being a Sec Gen. If it hadn’t been for Laam – he clutched his friend’s wrist – Peat wouldn’t be in Non-Land, he would have been excluded from his rightful place with his generation. Astra’s crimes were a betrayal almost impossible to grasp.

Laam massaged his neck, consoling with delicate pressure. Robin pressed closer too, sliding an arm round his hips. Feeling for Robin’s fingers, he leaned against Laam, touching his head to his friend’s, crying freely. Normally, he didn’t weep. Normally he was Peat: logical, dependable, the go-to guy for advice, the legal picture. But the counsellor was right, sometimes you couldn’t solve the crime. Sometimes you had to feel the feelings. Down his cheeks fell salty tears of grief and rage, mingled with sweet tears of gratitude for the second chance he had been given: the chance to be a Sec Gen. To know and love Laam and Robin and Jade and all his Sec brothers and sisters.

Where was Jade? The heart bond glowing stronger again, he lunged forward and wrapped his arms around his Sec sister, pressed his chest against her spine. He wasn’t the only person breaking ranks; around him the Sec Gens were clasping each other as close as they could. Breathing as one, a soothing rhythmic hush, his division watched Sheba’s smile give way to the cheeky grin of the boy from Cedaria – a boy whose only crime had been enjoying walnut-picking, whose brutal death had prevented a generation of children from being allowed to venture into their own woods.

There was deep comfort in the huddle, but Peat’s stomach was still tense. His mouth watered, his tongue curling against the iron taste of fear. Would photographs of Hokma and Astra flash up next? Would he have to endure their taunting smiles?

The boy’s face faded and darkness fell over the hall.

He braced himself.

‘Thank you, Sec Gens,’ Odinson boomed softly in his ear. ‘That was painful, very painful, I know, especially for those of you who lost family members. But you are Sec Gens. You are resilient, Coded with the ability to recover. To enter the darkness and return stronger than ever. By sharing your grief, you deepen your shared destiny: to protect Is-Land and save Gaia Herself. Please take as long as you need to regain your well-being.’

Odinson’s deep concern reverberated through the huddle. People hugged and stroked each other back to equilibrium. Jade caressed Peat’s arms. Laam kissed his shoulder blade. Peat’s cheeks were wet, his limbs weak.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...