- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Lou Clark has lots of questions. Like how it is she's ended up working in an airport bar, Or why the flat she's owned for a year still doesn't feel like home. What Lou does know for certain is that something has to change. But does the stranger on her doorstep hold the answers Lou is searching for - or just more questions? But Lou once made a promise to live. And if she's going to keep it, she has to invite them in…

Release date: September 29, 2015

Publisher: Penguin Books

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

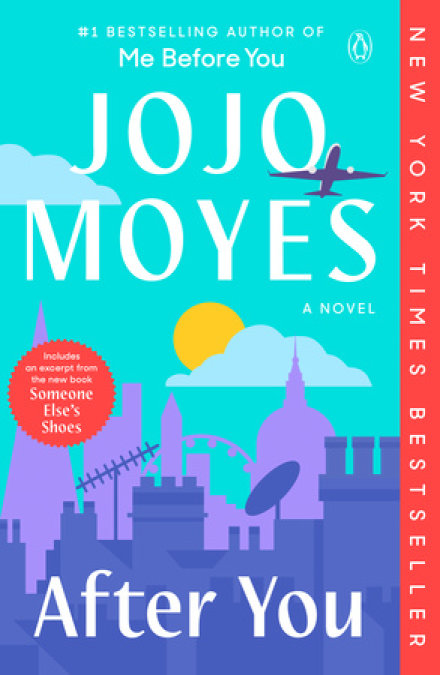

After You

Jojo Moyes

1

The big man at the end of the bar is sweating. He holds his head low over his double scotch and every few minutes he glances up and out behind him toward the door, and a fine sheen of perspiration glistens under the strip lights. He lets out a long, shaky breath disguised as a sigh and turns back to his drink.

“Hey. Excuse me?”

I look up from polishing glasses.

“Can I get another one here?”

I want to tell him that it’s really not a good idea, that it won’t help. That it might even put him over the limit. But he’s a big guy and it’s fifteen minutes till closing time and according to company guidelines, I have no reason to tell him no. So I walk over and take his glass and hold it up to the optic. He nods at the bottle.

“Double,” he says, and slides a fat hand down his damp face.

“That’ll be seven pounds twenty, please.”

It is a quarter to eleven on a Tuesday night, and the Shamrock and Clover, East City Airport’s Irish-themed pub that is as Irish as Mahatma Gandhi, is winding down for the night. The bar closes ten minutes after the last plane takes off, and right now it is just me, the intense young man with the laptop, the two cackling women at table 2, and the man nursing a double Jameson’s waiting on SC107 to Stockholm and DB224 to Munich, the latter of which has been delayed for forty minutes.

I have been on since midday, as Carly had a stomachache and went home. I didn’t mind. I never mind staying late. Humming softly to the sounds of Celtic Pipes of the Emerald Isle Vol. III, I walk over and collect the glasses from the two women, who are peering intently at some video footage on a phone. They laugh the easy laughs of the well lubricated.

“My granddaughter. Five days old,” says the blond woman, as I reach over the table for her glass.

“Lovely.” I smile. All babies look like currant buns to me.

“She lives in Sweden. I’ve never been. But I have to go see my first grandchild, don’t I?”

“We’re wetting the baby’s head.” They burst out laughing again. “Join us in a toast? Go on, take a load off for five minutes. We’ll never finish this bottle in time.”

“Oops! Here we go. Come on, Dor.” Alerted by a screen, they gather up their belongings, and perhaps it’s only me who notices a slight stagger as they brace themselves for the walk toward security. I place their glasses on the bar, scan the room for anything else that needs washing.

“You never tempted then?” The smaller woman has turned back for her scarf.

“I’m sorry?”

“To just walk down there, at the end of a shift. Hop on a plane. I would.” She laughs again. “Every bloody day.”

I smile, the kind of professional smile that might convey anything at all, and turn back toward the bar.

• • •

Around me the concession stores are closing up for the night, steel shutters clattering down over the overpriced handbags and emergency-gift Toblerones. The lights flicker off at gates 3, 5, and 11, the last of the day’s travelers winking their way into the night sky. Violet, the Congolese cleaner, pushes her trolley toward me, her walk a slow sway, her rubber-soled shoes squeaking on the shiny Marmoleum.

“Evening, darling.”

“Evening, Violet.”

“You shouldn’t be here this late, sweetheart. You should be home with your loved ones.”

She says exactly the same thing to me every night.

“Not long now.” I respond with these exact words every night. Satisfied, she nods and continues on her way.

Intense Young Laptop Man and Sweaty Scotch Drinker have gone. I finish stacking the glasses and cash up, checking twice to make sure the till roll matches what is in the till. I note everything in the ledger, check the pumps, jot down what we need to reorder. It is then that I notice the big man’s coat is still over his bar stool. I walk over and glance up at the monitor. The flight to Munich would be just boarding if I felt inclined to run his coat down to him. I look again and then walk slowly over to the Gents.

“Hello? Anyone in here?”

The voice that emerges is strangled and bears a faint edge of hysteria. I push open the door. The Scotch Drinker is bent low over the sinks, splashing his face. His skin is chalk-white.

“Are they calling my flight?”

“It’s only just gone up. You’ve probably got a few minutes.”

I make to leave, but something stops me. The man is staring at me, his eyes two tight little buttons of anxiety. He shakes his head. “I can’t do it.” He grabs a paper towel and pats at his face. “I can’t get on the plane.”

I wait.

“I’m meant to be traveling over to meet my new boss, and I can’t. And I haven’t had the guts to tell him I’m scared of flying.” He shakes his head. “Not scared. Terrified.”

I let the door close behind me.

“What’s your new job?”

He blinks. “Uh . . . car parts. I’m the new Senior Regional Manager bracket Spares close bracket for Hunt Motors.”

“Sounds like a big job,” I say. “You have . . . brackets.”

“I’ve been working for it a long time.” He swallows hard. “Which is why I don’t want to die in a ball of flame. I really don’t want to die in an airborne ball of flame.”

I am tempted to point out that it wouldn’t actually be an airborne ball of flame, more a rapidly descending one, but suspect it wouldn’t really help. He splashes his face again and I hand him another paper towel.

“Thank you.” He lets out another shaky breath and straightens up, attempting to pull himself together. “I bet you never saw a grown man behave like an idiot before, huh?”

“About four times a day.”

His tiny eyes widen.

“About four times a day I have to fish someone out of the men’s loos. And it’s usually down to fear of flying.”

He blinks at me.

“But you know, like I say to everyone else, no planes have ever gone down from this airport.”

His neck shoots back in his collar. “Really?”

“Not one.”

“Not even . . . a little crash on the runway?”

I shake my head.

“It’s actually pretty boring here. People fly off, go to where they’re going, come back again a few days later.” I lean against the door to prop it open. These lavatories never smell any better by the evening. “And anyway, personally, I think there are worse things that can happen to you.”

“Well, I suppose that’s true.”

He considers this, looks sideways at me. “Four a day, huh?”

“Sometimes more. Now if you wouldn’t mind, I really have to get back. It’s not good for me to be seen coming out of the men’s loos too often.”

He smiles, and for a minute I can see how he might be in other circumstances. A naturally ebullient man. A cheerful man. A man at the top of his game of continentally manufactured car parts.

“You know, I think I hear them calling your flight.”

“You reckon I’ll be okay.”

“You’ll be okay. It’s a very safe airline. And it’s just a couple of hours out of your life. Look, SK491 landed five minutes ago. As you walk to your departure gate, you’ll see the air stewards and stewardesses coming through on their way home and you’ll see them all chatting and laughing. For them, getting on these flights is pretty much like getting on a bus. Some of them do it two, three, four times a day. And they’re not stupid. If it wasn’t safe, they wouldn’t get on, would they?”

“Like getting on a bus,” he repeats.

“Probably an awful lot safer.”

“Well, that’s for sure.” He raises his eyebrows. “Lot of idiots on the road.”

I nod.

He straightens his tie. “And it’s a big job.”

“Shame to miss out on it, for such a small thing. You’ll be fine once you get used to being up there.”

“Maybe I will. Thank you . . .”

“Louisa,” I say.

“Thank you, Louisa. You’re a very kind girl.” He looks at me speculatively. “I don’t suppose . . . you’d . . . like to go for a drink sometime?”

“I think I hear them calling your flight, sir,” I say, and I open the door to allow him to pass through.

He nods, to cover his embarrassment, makes a fuss of patting his pockets. “Right. Sure. Well . . . off I go then.”

“Enjoy those brackets.”

It takes two minutes after he has left for me to discover he has been sick all over cubicle 3.

• • •

I arrive home at a quarter past one and let myself into the silent flat. I change out of my clothes and into my pajama bottoms and a hooded sweatshirt, then open the fridge, pulling out a bottle of white, and pouring a glass. It is lip-pursingly sour. I study the label and realize I must have opened it the previous night then forgotten to stopper the bottle, and then decide it’s never a good idea to think about these things too hard and I slump down in the chair with it.

On the mantelpiece are two cards. One is from my parents, wishing me a happy birthday. That “best wishes” from Mum is as piercing as any stab wound. The other is from my sister, suggesting she and Thom come down for the weekend. It is six months old. Two voice mails are on my phone, one from the dentist. One not.

Hi Louisa. It’s Jared here. We met in the Dirty Duck? Well, we hooked up [muffled, awkward laugh]. It was just . . . you know . . . I enjoyed it. Thought maybe we could do it again? You’ve got my digits . . .

When there is nothing left in the bottle, I consider buying another one, but I don’t want to go out again. I don’t want Samir at the Mini Mart grocers to make one of his jokes about my endless bottles of pinot grigio. I don’t want to have to talk to anyone. I am suddenly bone-weary, but it is the kind of head-buzzing exhaustion that tells me that if I go to bed I won’t sleep. I think briefly about Jared and the fact that he had oddly shaped fingernails. Am I bothered about oddly shaped fingernails? I stare at the bare walls of the living room and realize suddenly that what I actually need is air. I really need air. I open the hall window and climb unsteadily up the fire escape until I am on the roof.

The first time I’d come up, nine months earlier, the estate agent showed me how the previous tenants had made a small terrace garden, dotting around a few lead planters and a small bench. “It’s not officially yours, obviously,” he’d said. “But yours is the only flat with direct access to it. I think it’s pretty nice. You could even have a party up here!” I had gazed at him, wondering if I really looked like the kind of person who held parties.

The plants have long since withered and died. I am apparently not very good at looking after things. Now I stand on the roof, staring out at London’s winking darkness below. Around me a million people are living, breathing, eating, arguing. A million lives completely divorced from mine. It is a strange sort of peace.

The sodium lights glitter as the sounds of the city filter up into the night air, engines rev, doors slam. From several miles south comes the distant brutalist thump of a police helicopter, its beam scanning the dark for some vanished miscreant in a local park. Somewhere in the distance a siren wails. Always a siren. “Won’t take much to make this feel like home,” the real estate agent had said. I had almost laughed. The city feels as alien to me as it always has. But then everywhere does these days.

I hesitate, then take a step out onto the parapet, my arms lifted out to the side, a slightly drunken tightrope walker. One foot in front of the other, edging along the concrete, the breeze making the hairs on my outstretched arms prickle. When I first moved down here, when it all first hit me hardest, I would sometimes dare myself to walk from one end of my block to the other. When I reached the other end I would laugh into the night air. You see? I am here—staying alive—right out on the edge. I am doing what you told me!

It has become a secret habit: me, the city skyline, the comfort of the dark, and the anonymity and the knowledge that up here nobody knows who I am.

I lift my head, feel the night breezes, hear the sound of laughter below and the muffled smash of a bottle breaking, see the traffic snaking up toward the city, the endless red stream of taillights, an automotive blood supply. It is always busy here, above the noise and chaos. Only the hours between 3 to 5 a.m. are relatively peaceful, the drunks having collapsed into bed, the restaurant chefs having peeled off their whites, the pubs having barred their doors. The silence of those hours is interrupted only sporadically, by the night tankers, the opening up of the Jewish bakery along the street, the soft thump of the newspaper delivery vans dropping their paper bales. I know the subtlest movements of the city because I no longer sleep.

Somewhere down there a lock-in is taking place in the White Horse, full of hipsters and East Enders, and a couple are arguing outside, and across the city the general hospital is picking up the pieces of the sick and the injured and those who have just barely scraped through another day. Up here is just the air and the dark and somewhere the FedEx freight flight from LHR to Beijing, and countless travelers, like Mr. Scotch Drinker, on their way to somewhere new.

“Eighteen months. Eighteen whole months. So when is it going to be enough?” I say into the darkness. And there it is, I can feel it boiling up again, this unexpected anger. I take two steps along, glancing down at my feet. “Because this doesn’t feel like living. It doesn’t feel like anything.”

Two steps. Two more. I will go as far as the corner tonight.

“You didn’t give me a bloody life, did you? Not really. You just smashed up my old one. Smashed it into little pieces. What am I meant to do with what’s left? When is it going to feel—”

I stretch out my arms, feeling the cool night air against my skin, and realize I am crying again.

“Fuck you, Will,” I whisper. “Fuck you for leaving me.”

Grief wells up again like a sudden tide, intense, overwhelming. And just as I feel myself sinking into it, a voice says, from the shadows: “I don’t think you should stand there.”

I half turn, and catch a flash of a small, pale face on the fire escape, dark eyes wide open. In shock, my foot slips on the parapet, my weight suddenly on the wrong side of the drop. My heart lurches a split second before my body follows. And then, like a nightmare, I am weightless, in the abyss of the night air, my legs flailing above my head as I hear the shriek that may be my own—

Crunch

And then all is black.

2

What’s your name, sweetheart?”

A brace around my neck.

A hand feeling around my head, gently, swiftly.

I am alive. This is actually quite surprising.

“That’s it. Open your eyes. Look at me, now. Look at me. Can you tell me your name?”

I want to speak, to open my mouth, but my voice emerges muffled and nonsensical. I think I have bitten my tongue. There is blood in my mouth, warm and tasting of iron. I cannot move.

“We’re going to move you onto a spinal board, okay? You may be a bit uncomfortable for a minute, but I’m going to give you some morphine to make the pain a bit easier.” The man’s voice is calm, level, as if it were the most normal thing in the world to be lying broken on concrete, staring up at the dark sky. I want to laugh. I want to tell him how ridiculous it is that I am here. But nothing seems to work as it should.

The man’s face disappears from view. A woman in a neon jacket, her dark curly hair tied back in a ponytail, looms over me, shining a thin torch abruptly in my eyes and gazing at me with detached interest as if I were a specimen, not a person.

“Do we need to bag her?”

I want to speak but I’m distracted by the pain in my legs. Jesus, I say, but I’m not sure if I say it aloud.

“Multiple fractures. Pupils normal and reactive. BP ninety over sixty. She’s lucky she hit that awning. What are the odds of landing on a daybed, eh? . . . I don’t like that bruising though.” Cold air on my midriff, the light touch of warm fingers. “Internal bleeding?”

“Do we need a second team?”

“Can you step back please, sir? Right back?”

Another man’s voice. “I came outside for a smoke, and she dropped onto my bloody balcony. She nearly bloody landed on me.”

“Well there you go—it’s your lucky day. She didn’t.”

“I got the shock of my life. You don’t expect people to just drop out of the bloody sky. Look at my chair. That was eight hundred pounds from the Conran shop. . . . Do you think I can claim for it?”

A brief silence.

“You can do what you want, sir. Tell you what, you could charge her for cleaning the blood off your balcony while you’re at it. How about that?”

The first man’s eyes slide toward his colleague. Time slips, I tilt with it. I have fallen off a roof? My face is cold and I realize distantly that I have started to shake.

“She’s going into shock, Sam—”

A van door slides open somewhere below. And then the board beneath me moves and briefly the pain the pain the pain—everything turns black.

• • •

A siren and a swirl of blue. Always a siren in London. We are moving. Neon slides across the interior of the ambulance, hiccups and repeats, illuminating the unexpectedly packed interior. The man in the green uniform is tapping something into his phone, before turning to adjust the drip above my head. The pain has lessened—morphine?—but with consciousness comes a growing terror. It is a giant airbag inflating slowly inside me, steadily blocking out everything else. Oh, no. Oh, no.

“Egcuse nge?”

It takes two goes for the man, his arm braced against the back of the cab, to hear me. He turns and stoops toward my face. He smells of lemons and has missed a bit when shaving.

“You okay there?”

“Ang I—”

He leans down. “Sorry. Hard to hear over the siren. We’ll be at the hospital soon.” He places a hand on mine. It is dry and warm and reassuring. I am suddenly panicked in case he decides to let go. “Just hang in there. What’s our ETA, Donna?”

I can’t say the words. My tongue fills my mouth. My thoughts are muddled, overlapping. Did I move my arms when they picked me up? I lifted my right hand, didn’t I?

“Ang I garalysed?” It emerges as a whisper.

“What?” He drops his ear to somewhere near my mouth.

“Garalysed? Ang I garalysed?”

“Paralyzed?” He hesitates, his eyes on mine, then turns and looks down at my legs. “Can you wiggle your toes?”

I try to remember how to move my feet. It seems to require several more leaps of concentration than it used to. He reaches down and lightly touches my toe, as if to remind me where they are. “Try again. There you go.”

Pain shoots up both my legs. A gasp, possibly a sob. Mine.

“You’re all right. Pain is good. I can’t say for sure, but I don’t think there’s any spinal injury. You’ve done your hip, and a few other bits besides.”

His eyes are on mine. Kind eyes. He seems to understand how much I need convincing. I feel his hand close on mine. I have never needed a human touch more.

“Really. I’m pretty sure you’re not paralyzed.”

“Oh, thang Gog,” I hear my voice, as if from afar. My eyes brim with tears. “Please don leggo og me,” I whisper.

He moves his face closer. “I am not letting go of you.”

I want to speak, but his face blurs, and I am gone again.

• • •

Afterward they tell me I fell two floors of the five, bursting through an awning, breaking my fall on a top-of-the-line, outsized, canvas-and-wicker-effect, waterproof-cushioned sun lounger on the balcony of Mr. Antony Gardiner, a copyright lawyer and neighbor I have never met. My hip smashes into two pieces and two of my ribs and my collarbone snap straight through. I break two fingers on my left hand, and a metatarsal, which pokes through the skin of my foot and causes one of the medical students to faint. My X-rays are a source of some fascination.

I keep hearing the voice of the paramedic who treated me: You never know what will happen when you fall from a great height. I am apparently very lucky. They tell me this and wait, smiling, as if I should respond with a huge grin, or perhaps a little tap dance. I don’t feel lucky. I don’t feel anything. I doze and wake and sometimes the view is the bright lights of an operating theater and then it is a quiet, still room. A nurse’s face. Snatches of conversation.

Did you see the mess the old woman on D4 made? That’s some end of a shift, eh?

You work up at the Princess Elizabeth, right? You can tell them we know how to run an ER. Hahahahaha.

You just rest now, Louisa. We’re taking care of everything. Just rest now.

The morphine makes me sleepy. They up my dose and it’s a welcome, cold trickle of oblivion.

• • •

I open my eyes to find my mother at the end of my bed.

“She’s awake. Bernard, she’s awake. Do we need to get the nurse?”

She’s changed the color of her hair, I think distantly. And then: Oh. It’s my mother. My mother doesn’t talk to me anymore.

“Oh, thank God. Thank God.” My mother reaches up and touches the crucifix around her neck. It reminds me of someone but I cannot think who. She leans forward and lightly strokes my cheek. For some reason this makes my eyes fill immediately with tears.

“Oh, my little girl.” She is leaning over me, as if to shelter me from further damage. I smell her perfume, as familiar as my own. “Oh, Lou.”

She mops my tears with a tissue.

“I got the fright of my life when they called. Are you in pain? Do you need anything? Are you comfortable? What can I get you?”

She talks so fast that I cannot answer. “We came as soon as they said. Treena’s looking after Granddad. He sends his love. Well, he sort of made that noise, you know, but we all know what he means. Oh, love, how on earth did you get yourself into this mess? What on earth were you thinking?”

She does not seem to require an answer. All I have to do is lie there. My mother dabs at her eyes, and then again at mine.

“You’re still my daughter. And . . . and I couldn’t bear it if something happened to you and we weren’t . . . you know.”

“Ngung—” I swallow over the words. My tongue feels ridiculous. I sound drunk. “I ngever wanged—”

“I know. But you made it so hard for me, Lou. I couldn’t—”

“Not now, love, eh?” Dad touches her shoulder.

Her words tail off. She looks away into the middle distance and takes my hand. “When we got the call. Oh. I thought—I didn’t know—” She is sniffing again, her handkerchief pressed to her lips. “Thank God she’s okay, Bernard.”

“Of course she is. Made of rubber, this one, eh?”

Dad looms over me. We had last spoken on the telephone two months earlier, but I have not seen him in person for the eighteen months since I left my hometown. He looks enormous and familiar and desperately, desperately tired.

“Shorry,” I whisper. I can’t think what else to say.

“Don’t be daft. We’re just glad you’re okay. Even if you do look like you’ve done six rounds with Mike Tyson. Have you actually looked in a mirror since you got here?”

I shake my head.

“Maybe . . . I might just hold off a bit longer. You know Terry Nicholls, that time he went right over his handlebars by the Mini Mart? Well, take off the mustache, and that’s pretty much what you look like. Actually”—he peers closer at my face—“now that you mention it . . .”

“Bernard.”

“We’ll bring you some tweezers tomorrow. Anyway, the next time you decide you want flying lessons, let’s head down the ol’ airstrip, yes? Jumping and flapping your arms is plainly not working for you.”

I try to smile.

They both bend over me. Their faces are strained, anxious. My parents.

“She’s got thin, Bernard. Don’t you think she’s got thin?”

Dad leans closer, and then I see how his eyes have grown a little watery. How his smile is a bit wobblier than usual.

“Ah . . . she looks beautiful, love. Believe me. You look bloody beautiful.” He squeezes my hand, then lifts it to his mouth and kisses it. My dad has never done anything like that to me in my whole life.

It is then that I realize they thought I was going to die and a sob bursts unannounced from my chest. I shut my eyes against the hot tears and feel his large, wood-roughened palm around mine.

“We’re here, sweetheart. It’s all right now. It’s all going to be okay.”

• • •

They make the fifty-mile journey every day for two weeks, catching the early train down, and then after that, come every few days. Dad gets special dispensation from work because Mum won’t travel by herself. There are, after all, all sorts in London. This is said more than once and always accompanied by a furtive glance behind her, as if a knife-wielding hoodlum is even now sneaking into the ward. Treena is staying over to keep an eye on Granddad. There is an edge to the way Mum says it that makes me think this might not be my sister’s first choice of arrangements.

Mum has brought homemade food to the hospital ever since the day we all stared at my lunch and, despite five whole minutes of intense speculation couldn’t work out what it actually was. “And in plastic trays, Bernard. Like a prison.” She prodded it sadly with a fork, then sniffed the residue. She now arrives daily with enormous sandwiches—thick slices of ham or cheese in white bloomer bread—and homemade soups in flasks (“Food you can recognize”) and feeds me like a baby. My tongue slowly returns to its normal size. Apparently I’d almost bitten through it when I landed. It’s not unusual, they tell me.

I have two operations to pin my hip, and my left foot and left arm are in plaster up to my joints. Keith, one of the porters, asks if he can sign my casts—apparently it’s bad luck to have them virgin white—and promptly writes a comment so filthy that Eveline, the Filipina nurse, has to put a plaster on it before the consultant comes around. When Keith pushes me to X-ray or to the pharmacy, he tells me the gossip from around the hospital. I could do without hearing about the patients who die slow and horrible deaths, of which there seem to be an endless number, but it keeps him happy. I sometimes wonder what he tells people about me. I am the girl who fell off a five-story building and lived. In hospital status, this apparently puts me some way above the compacted bowel in C ward, or That Daft Bint Who Accidentally Took Her Thumb Off With Pruning Shears.

It is amazing how quickly you become institutionalized. I wake, accept the ministrations of a handful of people whose faces I now recognize, try to say the right thing to the consultants, and wait for my par

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...