Elegant white clouds floated in a perfect blue sky, casting shadows over fields of scarlet and gold tulips. A rippling wind moved through the fields, the only thing daring to intrude on perfect stillness. Its fearlessness caused the flowers to bob and weave like maids in a row. In the distance, along a well-worn path, an ancient windmill stood solemnly guarding the field. It towered above its budding subjects, its brown clapboard walls strong but worn, peeling and relentless against the passage of time. The red sails, now faded to time-worn pink, caught the wind and groaned a rhythmic chant as they creaked and toiled.

Bounding toward the windmill, a new bride ran ahead in playful chase away from her bridegroom through the rows of nodding tulips. Sarah, barely twenty-two, was already dressed for her honeymoon. A simple cream-colored cotton dress hung loosely from her delicate shoulders. Cream sandals emphasized her shapely ankles and her long legs, kissed generously by the early spring sun as she sprinted ahead of her husband.

Just a few short hours since exchanging vows, much of Sarah’s wedding finery had already been carefully packed away in sheets of soft, white tissue paper. The satin shoes that buckled at the ankle, along with her dropped-waist, calf-length, silk dress, had been reverently tucked and folded by elderly female relatives and young unmarried friends. It was all nestled now in her mahogany chest, ready to delight the expected stream of family brides ahead of her.

Everything put away except the one thing she couldn’t yet bear to surrender. Apart from the gold wedding band on her left hand, the only thing distinguishing her as a newly married woman streamed out behind her, waltzing on the wind—an antique lace veil, trimmed by her grandmother’s aged and gnarled fingers, the exquisite fabric a bouquet of intricate daisy-chain stitches and miniature cream pearls.

As she ran along the colorful path, the wind picked up, a foil in the young couple’s romp. All at once, a mischievous gust bridled her, tugging at the train and twisting it into a carefree, corkscrewed spiral that danced up into the sky. Josef caught up, through the lines of flowery guards, and leaped out in front of her. He was dressed in pleated linen trousers, and a blue linen shirt rolled to the elbows, exposing long, athletic forearms. His body was willowy but strong, and a shock of raven hair framed a face with piercing, expectant blue eyes.

He reached out, grabbing her around the waist, and pulled her toward him, playfully pinning her arms behind her back to gather her even closer. Her hot breath came in sharp, short gasps that warmed his cheek.

“Finally,” he said triumphantly.

Sarah responded by giggling and trying to wriggle free as Josef attempted to unpin her veil. “I’m not giving it up, Josef. I plan on wearing it through the whole of my first year of marriage!”

Josef’s eyes widened in amusement. “My mother would be horrified, since she already has plans to use it to trim our children’s baptismal gowns.”

“Children?” Sarah echoed. “We’ve only been married for four hours.”

“Well, then,” he said, in a decisive tone. “There is no time to lose!” Releasing her hand, he cupped her face, kissing her eyes, lips, and neck as she giggled in an attempt to squirm away from his advances.

“Not my neck, Josef. You know what that does to me.”

Flashing her an all-knowing smile, he wrapped his arms around her, his mouth finding hers in a passionate kiss. In the distance, a voice called for them.

Sarah grabbed Josef by his shirt collars and pulled him down into a dip among the tulips as the long veil, whipped up by the wind, entwined the pair of them.

“Shhh,” she whispered. “If we stay still and out of sight, Mama will not find us.”

“I’m not complaining,” Josef whispered, pulling down the billowing fabric that had encircled his face. He adjusted their position, laying an arm beneath her to protect her head from the stony earth.

They lay facing one another, waiting wordlessly for the footsteps to fade, their breath slowing into a unified rhythm. Deep in the heart of the field, the scent from the tulips was intoxicating. Sarah rose on one elbow and looked down at Josef with thoughtful eyes.

“I loved your father’s gift,” she whispered.

Josef shook his head and smiled. “My father is a romantic and always has been. He puts all his faith in the power of words of love.” Josef rolled onto his back and interlinked his hands behind his head, looking up toward the wispy clouds. “I can’t believe he read poems at our wedding. When I’m a mathematician! What do I need with such things? I think he holds out hope that one day, somehow, his precious poetry will find room in my heart. Even now at the age of twenty-eight.”

Sarah pressed her lips together and thrust out her chin. “How can you say that? What is life without art, music, or poetry? It helps us know how to feel, love, and live!” She rolled onto her back and focused on a cloud that looked like a cantering pony. Coyly, she added, “I started to fall a little bit in love with your father as I watched him reciting. The way he looked at your mother showed all the love they’d shared for so long.”

A look of real surprise crossed Josef’s face.

Sarah continued, sighing, “I’m not sure how long our love will last if you don’t know how to keep love alive like that. I can’t see mathematical equations making me feel quite the same way.”

Rolling toward her, he brushed aside an auburn curl from her heart-shaped face. “What do you mean? Mathematics can be beautiful. Euler’s Identity is said to be the most beautiful equation in the world.” He continued with intense romantic emphasis, “eiπ + 1 = 0.”

Sarah closed her eyes and wrinkled up her nose as she shook her head, flicking her copper curls to flash her displeasure.

He pulled her in close again and whispered into her ear, “How shall I keep my soul from touching yours? How shall I lift it out beyond you toward other things?”

Opening her eyes fully, Sarah broke into a broad smile as he continued to recite the poem “Love Song” by the contemporary poet, Rainer Maria Rilke. She showed her appreciation by covering his face with tiny birdlike kisses and then slowly unbuttoning his shirt.

He continued to whisper the words of the poem as he nuzzled her neck and caressed her body.

“All right,” she whispered, “you can have the veil. What shall we call our son?”

He looked deep into her eyes before answering. “Sarah.” He smiled assuredly. “It will be a daughter and we will call her Sarah.”

She started to protest before he silenced her by covering her mouth with a lingering kiss. As their lovemaking fell into a gentle rhythm, all that could be heard was the soft creaking of the windmill as its sails lifted toward the darkening sunset sky.

His vision, from the constantly passing bars,

has grown so weary that it cannot hold

anything else. It seems to him there are

a thousand bars; and behind the bars, no world.

—Rainer Maria Rilke, “The Panther”

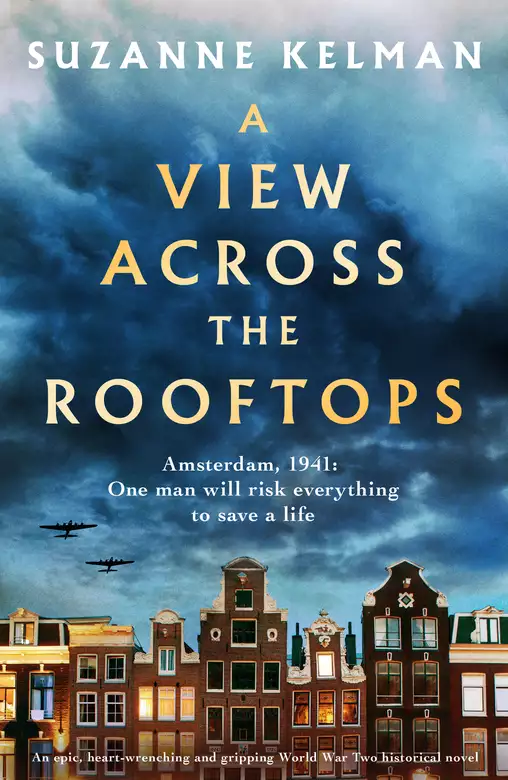

Relentless, biting snow fell in icy sheets upon the war-torn streets of occupied Holland, forging heaps of gritty gray slush, suffocating a town already stripped of its humanity. The steely mounds of snow were pockmarked by ugly splatters accumulated from a week of frigid temperatures, dirty roads, and ricocheting stones splayed by hapless drivers. Gray snow on gray streets smothered by a bilious sky of the same dispiriting color. To the Dutch, this bleak weather reflected a world that felt the same.

Down a dark residential street came the hollow echo of hobnailed boots, the now-familiar sound of a column of marching Nazis. As the feet pounded the roadway, the cadence grew ominous in its rhythmical element, each hammered step casting forth a web of piercing foreboding, like a pound of steel nails shaken aggressively in a tin box. In the nine months of occupation, the Third Reich had already proven itself an evil beast not to be trifled with, a bloodthirsty jackal, primed and alert, ready to take down and devour whatever stood between it and conquering for the Führer.

Amsterdam, once lively and carefree, with an opulent brilliance, the apple of the Netherlands’ eye, had high hopes of defeating the invading forces, but instead, as the rest of Holland, fell to German Blitzkrieg in just four days. Its heart now stood wrenched open and forever wounded. Its previously unblemished optimism, not unlike the heaps of ice on the ground, forever tarnished, pebble-dashed and smothered by the dark forces of evil that had also arrived in gray.

As the sound became deafening on the quiet city street, behind locked doors and shuttered windows, fearful faces froze, eyes closed in silent prayer. Chilled souls hoping that their one defiant act of un-parted curtains would signal their united scream of resistance, allowing them to hang onto the last strands of their civility. The footfalls faded, but the fear lingered much longer than the echoes. Only once there was total silence did they allow themselves the luxury to breathe and return to the business of surviving. Thanking God once again—not this street, not this day.

Across town, a ticking clock matched the rhythm of the marching feet. Professor Josef Held stared at its white face and sharp, black hands, unaware of the dangerous rhythm it marked time with. The clock hung high on a wall, watching over a large classroom filled with rows of students. A high ceiling held aloft by ornate limestone cornices gave way on one side to dusty but ordered bookcases, and on the other to an elegant bank of windows.

Professor Held worked wordlessly, grading papers at his desk. An awkward middle-aged man of forty-seven, seemingly uncomfortable in his own skin, he rarely looked up. When he did, a ghost of handsomeness lingered about him. It seeped out through his perfect blue eyes and striking black hair, only beginning to gray at the temples. And even though he had spent his life bent over this one desk, somehow his body managed to retain a semblance of youthful tautness more suited to a retired athlete than an unassuming mathematics professor.

In his classroom, the regime of marching soldiers seemed far away as diligent students set their minds to work, with shirtsleeves rolled to the elbows and heads bent over heavy oak desks. Other than the ticking of the clock, there was nothing to hear except the occasional hushed cough or a busy pencil scratching dry paper. The room seemed timeless, and the hours endless. As the hands of the clock finally met at the midday hour, a weak sun fought its way through the hopeless slate sky and grazed the high windows.

Held exchanged one math paper for another, and stopped. Upon the sheet in front of him there was no math, no answers to the numbered problems. Instead the page was covered with a poem, “Panther,” written by Rilke, his late wife’s favourite poet. Shaking his head, he sighed, exasperated, not wanting to think about Sarah today. He took off the silver-rimmed glasses that were a well-chosen prop for a man who wanted to buffer himself from the outside world. Gently he placed them on the desk and rubbed his eyes before replacing them, one loop of hooked wire at a time, back on his face. He looked at the clock and cleared his throat. “Class dismissed. Mr. Blum, I need a moment of your time.”

University students quietly filed out the door, escaping the stifled silence of the room. One student, Elke Dirksen, her lovely eyes filled with concern, lingered in the doorway as she watched Michael Blum stride toward the front. With his good looks, Michael seemed like the best of what youth could offer. Twenty-two years old, vibrant, and with a restless charisma. Michael’s eyes sparkled with defiant humor as he winked at Elke in the corridor.

Professor Held waited at his desk for the classroom to empty while he stacked his papers into an orderly pile. As the room grew silent and the door closed, he pulled Michael’s paper to the top. He spoke directly to him without looking up. “You are aware, Mr. Blum, that this is an advanced mathematics course.”

Michael laughed.

After many years of teaching, Held was unaffected by insolence. “This is not the first time we have had this discussion. You have written on your assignment again rather than solving the formula as requested.”

Michael balked. “What? You don’t like Rilke?”

Professor Held continued, “That has nothing to do with it. Poetry belongs in books, not on mathematics papers.”

A sharp intake of breath from Michael lasted a split second before it dissolved into a tone of controlled bitterness that brimmed just under his words. “It’s no longer so easy for me to just buy… books. Do you even know who he is?”

For the first time, the older man looked up. “I beg your pardon?”

Michael became animated, enthusiastic even. “Rainer Maria Rilke. The poet? He is considered one of the most romantic—”

Professor Held tried to stop Michael short with a raised hand.

Michael’s face registered angry frustration. Then he continued, “Look, none of this matters anyway, because today is my last day.”

Professor Held lowered his eyes and dragged a new pile of papers toward himself. As he did, he pushed Michael’s paper across his orderly desk. “Please complete the assignment.”

Michael shook his head. “Today. Is. My. Last. Day. I am not going to sit here waiting for them to come after me. And I will not be forced into the Arbeitseinsatz.”

Held looked up briefly. So many of the young men were being forced into working in German factories; resisting could be dangerous. He wanted to say as much, but instead he retreated back behind the safety of his wall.

“Still, you need to complete this assignment.”

Michael snatched up the paper. As he leaned forward, a flyer fell out of his satchel onto the desk. The corner was torn off. Michael had obviously ripped it down, probably in anger. It was instructions ordering all the Jewish people to register. Both men stared at it and froze. The ticking clock and muffled sounds in the hallway filled the deafening space between them. Held realized all at once that Michael was Jewish, and he felt helpless, wordless. Wanted to take back his severe manner, but before he could say anything, Michael picked up the math paper and slowly and defiantly crumpled it into a ball and dropped it on the professor’s desk.

“Do you honestly think that any of this is important? The courage to fight and to love—that’s all that is important right now. And you won’t find any of that in a mathematical formula.”

Slowly pushing his glasses farther up his nose, Professor Held stared at the ball of crumpled paper.

Elke opened the door. “Michael! Come now!”

The sound of marching feet echoed down the hall toward the classroom. Michael moved swiftly toward the door.

Held opened his desk drawer and pulled out a book. It was a well-worn copy of Rilke’s New Poems. He signaled to his young student. “Before you go, Mr. Blum––”

Michael turned and Held pushed the book across the desk. Michael approached, curious, in spite of himself. Noting the title, he opened it reverently. Held watched him read the inscription on the first page, handwritten by his father.

“To Josef. Sometimes the most courageous love is whispered in the quietest moments.”

Meaningless words from a very long time ago, Held mused. He returned to his papers and with a dismissive wave of his hand muttered, “Keep it.”

Michael clasped the book to his chest. “Really? Thank you. Thank you, very much.”

Uncomfortable with this show of emotion, Held pushed his spectacles higher up his nose and nodded, shuffling papers awkwardly about the desk.

Michael turned to leave and then stopped at the door. “I guess it’s safe to tell you now that I hate mathematics.”

Held scoffed, then muttered, more to himself than to Michael, “So I have surmised.”

As Michael reached the door, Elke pulled him quickly by the arm into the corridor.

Held noted the empty place where the book had sat unopened for many years. He took a deep breath and closed the drawer. He was about to return to his grading when he noticed something on his desk. Gingerly, he picked up the flyer Michael had dropped.

The classroom door opened, and Held called out, “Mr. Blum, you forgot…”

But instead of Michael, he was surprised by Hannah Pender. The new university secretary, a striking woman with fine cheekbones and thoughtful blue eyes, was rarely seen away from the front desk. Her clothes today, he noticed, were a dark blue A-line skirt, that hugged her hips and emphasized her shapely legs, and an ivory-coloured blouse with a lacy neckline. As she walked in, she spoke in perfect German to a serious-looking Nazi officer who followed.

A small group of soldiers accompanied him and stood to attention outside the door, their severe gray uniforms sharp-edged and out of place against the elegant high-banked windows and pleasant wood-paneled hallway.

“This is Professor Held,” Hannah said. “He tutors advanced mathematics.” She approached his desk. “Hello, Professor. We are just checking on your students.”

Held responded, bewildered, “My students? My room is empty.” Under his desk, he clutched the census notice in his hand. He didn’t need any questions about why he had it or why it had been torn down.

Hannah smiled nervously and nodded.

The Major walked purposefully around the classroom, taking in every detail. Stopping at the large arched windows, he looked up, seemingly mesmerized by a spider building a web in a high corner outside. As the spider bobbed and wove its gossamer threads, a gentle breeze captured its work and rocked it like a hammock at sea. In the classroom, the only sound, the ticking clock, built its own tension with each stroke marking time. A bead of sweat formed across the bridge of Held’s nose under the rim of his glasses, and he quickly swiped it away with his free hand. The Major turned slowly to face Held.

“Professor Held? Interesting name.”

The professor nodded slightly.

The soldier approached the desk, speaking in German. “I believe that word is the same in Dutch as it is in German, meaning ‘hero.’ I hope you are not planning on being one.”

Held methodically pushed his spectacles farther up his nose and looked up at the officer, answering him in Dutch. “I’m afraid I am.”

A curious expression crossed the soldier’s face, accompanied by a forced smile; he knotted his eyebrows as if he were weighing up the professor.

Held continued with his well-versed return. “I teach literature students who would rather be learning the classics than how to understand algebra.”

The soldier realized the professor was joking and laughed. A forced, overblown laugh meant for show, controlling and demanding attention. He recovered quickly and took a long, hard moment to scan Held’s desk as he nodded slowly.

Professor Held shifted in his seat and glanced at the wall clock. “Is there anything else? If you don’t mind, Mrs. Pender, I do have to prepare. I have another class arriving soon.”

Ignoring him, the Major walked back toward the window and looked out at the icy view once more. Through the feeble shafts of sunlight, columns of sleeted snow started to fall again. Mrs. Pender smiled awkwardly at Professor Held. As they waited, the air between them felt like it tightened. Eventually, the captain turned. “I think teaching is a fine profession and, as long as you keep your heroics to algebra, things will go well for you.”

With that, the Major nodded before striding out of the room. Mrs. Pender followed. Held waited until the footsteps faded before letting out a ragged breath. He screwed up the census notice and dropped it into his wastepaper basket.

He stood and stretched before walking to a cupboard at the back of his classroom, where he took out a small key from his waistcoat breast-pocket to unlock the door. The cupboard was completely empty except for a pristine wireless with a rich, mahogany veneer. Held reached in and turned the large dial. The display glowed, and the wireless crackled into life. Lilting classical music filled the dry space and cut through the suffocating air. Sitting back down at his desk, he removed his glasses, closed his eyes, and took a deep, slow breath.

At the end of the day, Held added a new equation to the blackboard to be solved by his first class, wrapped a wool scarf tightly around his neck, and put on his coat. With his hat and satchel in hand, he exited the classroom. Moving wordlessly through the corridors, his eyes cast down, he gave an air of deliberate aloofness. As a result, no one talked to him or even acknowledged him. It was as if he were invisible. Making his way to the university’s main desk, he noted Hannah Pender instructing a young woman about her duties.

Mrs. Pender turned and spoke. “Oh, and here is Professor Held,” she said to the young girl. “Good evening, Professor. You will want your mail.”

Held nodded.

Hannah turned to instruct her protégée about which pigeonhole to fetch it from. As she moved around behind her desk Held pretended to be focused on the mathematics book he was holding, but couldn’t resist giving her a sideways glance. She was very attractive, he mused, more attractive than the woman who had just retired from the same job. She had been square-built, with wiry hair, a constant look of disappointment, and the beginnings of a mustache. This new secretary, this Hannah Pender, was very different.

“So sorry about the intrusion today, Professor,” she continued, turning to him as he looked down quickly toward his hands. “We have so much to do, and we have the German Army to answer to as well. As if I weren’t busy enough. And now I have this young girl, Isabelle, all they could spare me, who I have to train, and as you know I have only been here a few weeks myself…”

As she chattered on, Held waited, watching her, trying not to draw attention to the fact he was studying the shape of her face and her soft brown curls.

Isabelle, a mousy girl with wispy, brown hair tamed into a hairclip, appeared at Hannah’s side and handed her a bundle of mail, which Hannah then presented to Held. Hannah continued to chat about the weather, her workload, and the drop in enrollment as he quietly shuffled through his letters. As she leaned forward to await his instructions he caught a wisp of her perfume, violets or maybe it was lilac. Not wanting her to see how much of a distraction it was to him he hastily replaced a couple of pieces of mail on the desk and put the rest in his bag, turning quickly and saying, “Good evening, Mrs. Pender.”

Hannah took his discarded mail and smiled. “Good evening, Professor.”

Held nodded, put on his hat, and walked quickly toward the main door.

Out on the street, the morning chill had returned to herald the evening. Pulling his hat down farther on his head, he moved mutely through the streets on a well-worn route toward home. After picking up his evening groceries, he turned into Staalstraat, where a commotion of angry, volatile voices confronted him. A young couple were having an altercation with a German officer. People everywhere stopped, watching from a safe distance. Helpless despair hung in the air as thick as the blanket of cold around them. Held noted people’s faces—the shock and the horror, but also the fear, as if any of them could be next.

The soldier was yelling something about identiteitsdocumenten and the young woman started to cry, pleading she was on the way to the doctor and just forgot to pick them up. Held turned and kept moving, keeping his head down, deliberately looking in the opposite direction as the woman started to scream. He assured himself this would all be over soon. It had to be. He picked up his pace as he turned into his street. Still able to hear the echoes of the Jewish woman screaming, he tightened his scarf around his ears to block it out.

He pulled out a key as he reached the stone steps that led to the simple brown door of his three-story house. Behind him, the sound of two soldiers marching encouraged him to unbolt the lock and step inside without hesitation.

Putting down his satchel and small cloth shopping bag, he turned on the light. It illuminated a life that was neat and functional but devoid of warmth. A young gray cat raced up the hall to meet him, meowing incessantly. Held came to life. “Hello, Kat, I brought you a little something from the market. How was your day? Mine was interesting.”

Following Held up the hallway and into the kitchen, Kat watched intently as he put out scraps of fish in a bowl and then made himself a cup of tea.

He looked at the clock on his kitchen wall. “It is almost time,” he informed Kat. “I wonder what it is going to be tonight.”

Above the sink in his kitchen, he unlatched the heavy shutters and opened the windows wide. Methodically, he began his nightly ritual. First, he carefully arranged a chair to face toward the window, then he sat, added a plain woolen blanket to his knee and, with tea in hand, waited expectantly.

The cat jumped up into his lap. The last weak rays of evening light illuminated the darkness and streamed across his face. All at once, the awaited event began. Delightful piano music from next door danced through the window.

He educated Kat as he stroked his lean body. “Ah, Chopin, one of the nocturnes.”

He closed his eyes and took a deep breath.

Michael gazed down at Elke; her eyes were closed and her soft brown lashes still. Her long, chestnut hair, ends damp with perspiration, lay heavy upon her chest, masking her bare breasts. He leaned down and kissed her lips. As he pulled away, dragging the sheets to just under her chin, she moaned.

“No more, Michael, I’m tired.”

Moving his hands below the sheets, he started to stroke the length of her body with just the tips of his fingers.

“Stop.” Her eyes flashed, confrontational. “Don’t you know there is a war on? We should conserve our energy.”

Michael lifted himself gently on top of her, enjoying the feel and weight of their naked bodies pressed together as he whispered into her hair, “That is exactly why we should be making love. Who knows how long we have left.”

Playfully, she pushed him off her and returned the sheet close to her chest. She sat up and ran her hand through her messy hair. “Do you want some coffee?”

Michael sighed, rolled onto his back, and nodded. “If that’s the best you can offer.”

Giggling, she jumped up, taking the sheet with her and wrapping it around herself toga-style, leaving him naked on the bed.

As she moved toward the front of her houseboat, she looked back at him stretched out the length of the bed, as he pretended not to care he was naked and sheet-less.

“I am just going to lie here until you are overcome by my incredible body and beg me to make love to you again,” he informed her.

She shook her head before moving to the kitchen to make coffee and, standing waiting for the kettle to boil, looked over at her latest painting—an unfinished vase of sunflowers she’d been working on—with a self-critical eye. Michael noticed her shiver, her body reacting to a night that had descended into bitter cold again. When he heard the kettle boiling, he stood and dressed himself in her orange robe that he had found on the back of the bedroom door. He grabbed the book of poetry, the one Professor Held had given him, from the nightstand and joined her in the small galley kitchen.

Elke smiled at his ensemble, but her look changed to concern as she noted what he was carrying. “You should be careful. You know you’re not supposed to have books.”

Michael puffed out his cheeks as he flicked through the pages. “Let them try and take it from me. They can take away my freedom, but they can’t suppress my thoughts or mind. I refuse to give them either of those.”

Worry crept into her tone. “What will you do now though? These new laws are saying you can’t go out after 9 p.m., read books, study…’

Michael shut the book thoughtfully. “I haven’t given it much consideration, but maybe I’ll stay here, write poetry, and cook food for you all day. Imagine the sheer luxury of hiding away writing poems day after day.”

“No, seriously. Have you thought of leaving? I’m not sure how difficult it would be, but maybe you need to try.”

“And go where? I am Jewish. And even though I haven’t practiced my faith since my grandmother’s death, still that’s how our new German guests see me. There is no place for me right now. Besides, I would never leave my beloved Amsterdam, nor you.”

She smiled and interlocked her fingers with his. “This is the first time I have really heard you talk about your faith. Does it worry you that I am not Jewish?”

He looked at her with surprise. “I barely feel Jewish myself. Yes, it is my race. And yes, when I was young I went to the synagogue. And I suppose I liked the way the Rabbi recited the Torah, but I stopped believing in God, when He took all of my family from me.” He found it hard to keep the pain from his voice as he continued. “As you know, my father was in the Great War, so it wasn’t exactly a shock when he died because of his injuries, but when my mother was struck down with tuberculosis a year later and I had to watch her fight for her every breath, and my grandmother died just weeks after, I knew I could never believe in a just and kind God again. E

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved