- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

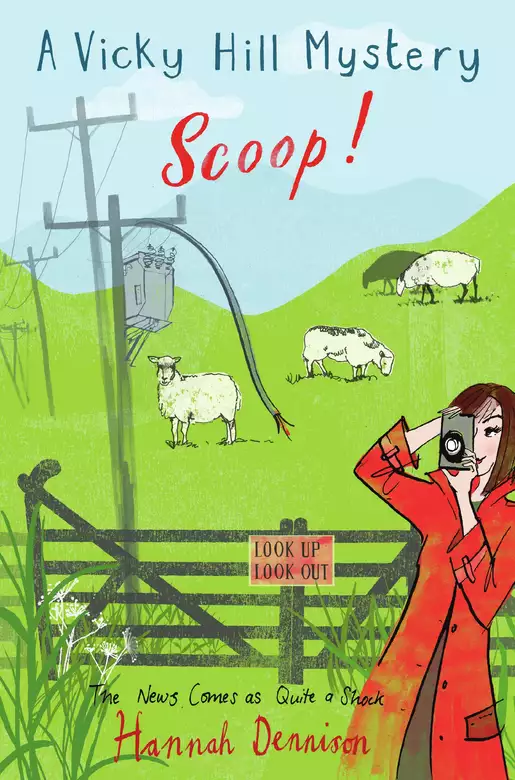

Synopsis

Vicky will do anything to get off the obituary circuit and on to the front page! If there's one thing Vicky has learnt as an obituary writer, it's how to spot something fishy at a funeral - and plenty is amiss at the service for Gordon Berry. The man was a champion hedge cutter so why are people willing to believe he electrocuted himself by striking a power line with his own clippers? At the reception there are rumblings of foul play - not to mention a fistfight between a mourner and the local Lothario. And in her quest for a scoop, Vicky will find she has to confront everything - from bad dates to mortal danger...

Release date: May 17, 2012

Publisher: C & R Crime

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Vicky Hill Mystery: Scoop!

Hannah Dennison

Take last Thursday’s freak accident. Sixty-five-year-old Gordon Berry had been tragically electrocuted while cutting a roadside hedgebank at Ponsford Cross. Apparently, his tractor-mounted articulated flail struck an overhead power line.

The coroner had returned a verdict of accidental death, and usually, I saw no reason to doubt it had there not been a brand-new warning sign saying look out! look up! Furthermore, Gordon Berry was one of Gipping’s champion hedge-cutters and not the kind of man to make such an elementary mistake.

Armed with these potentially incriminating facts, I set off for the service with a spring in my step. There were bound to be tons of prospective suspects attending and I couldn’t think of a better place to start my investigation.

The chosen venue was Gipping Methodist Church just off Water Rise and close to the River Plym. Formerly a Quaker meeting house, it was a dark-brick, rectangular building with a pitched roof. The front entrance was set back only a few yards from the pavement with a narrow path leading to the cemetery behind, giving excellent views of the river and distant moors.

Twelve mourners were already there, huddling outside the church door, stamping their feet to keep out the March cold. I thought back to my first few funerals and how I would panic if I weren’t at my post at least fifteen minutes before the church organist. Now, I knew absolutely everybody on the funeral circuit and only had to ask the identities of out of towners.

I jotted down the names; they were the usual suspects. Since Gordon Berry had been such a well-known figure in the farming community, a splashy ‘do’ was to follow at Plym Valley Farmers Social Club in Bridge Street.

‘Good morning,’ said a familiar voice.

I did a double take at the plump, dowdy young woman standing in front of me. She was dressed in a black suit, thick black stockings, and a black cloche hat and veil pulled firmly down over her face. I’d wondered why The Copper Kettle had been closed this morning, and now I knew.

‘Topaz Potter!’ I cried. ‘I hardly recognized you. Have you put on weight since yesterday?’

‘Ethel Turberville-Spat. One t,’ she said coldly. Then, glancing over her shoulder to make sure we wouldn’t be overheard, she added, ‘I’m in disguise, silly. It’s padding.’

It was the first time I’d ever seen Topaz at a funeral. ‘What are you doing here? Shouldn’t you be at the café?’

‘Berry lived in one of the estate cottages,’ she said. ‘I’m paying my respects.’

‘He died on your land?’

‘Apparently, yes.’ Topaz lowered her voice and looked over her shoulder, again. ‘I need to talk to you,’ she whispered. ‘It’s frightfully important. But not here.’

‘It’s about Berry, isn’t it?’ I said with growing excitement. I knew it! I knew there was something fishy about his death.

‘Come to The Kettle at four.’ She gave a little nod, said, ‘Excuse me,’ and strode into the church. Farmers doffed their caps. One lady curtsied. I marvelled that no one recognized the mop-capped young woman from the local café. The deference these country folk showed her made me wonder if I really knew Topaz at all. I was so used to seeing her as a waitress, I tended to forget she’d inherited The Grange from her aunt and was now lady of the manor.

As a steady flow of mourners filed past me into the church, I caught snatches of conversation: ‘Mary’s strong . . . he knew how to dig up a bank . . . sheep’s got worms . . .’ and, ‘I bet the bloody jumpers did him in.’

My stomach flipped over at that last remark. I spun round to see the large form of Jack B. Webster from Brooke Farm, disappear into the church. Jack Webster was not only Gordon Berry’s neighbour, but also an avid cutter himself and was bound to have some theories to share. I hadn’t considered the ongoing feud between the Gipping hedge-cutters and hedge-jumpers, but I certainly would now.

Although the little-known sport of hedge-jumping had been around for years, it was only now growing in popularity. This was partly due to the promotional efforts of celebrity hedge-jumper Dave Randall – one of my ex-beaus – and the exciting news that Great Britain was to host the Olympics in 2012. Dave Randall had been campaigning tirelessly to get hedge-jumping accepted as an Olympic sport.

I often thought back to that night with Dave when I’d seriously contemplated a night of hot sex, which luckily came to nothing. We hadn’t seen each other since I’d saved his life and frankly, I wasn’t bothered. Dad said it often happens on the job – moments of intimate bonding in times of terror then, when it’s all over, you find you have nothing in common.

A chorus of laughter interrupted my visit down memory lane. It seemed inappropriate given the circumstances. I took a few steps back and peered down the narrow path leading to the cemetery.

Dressed in a black wool coat, tall, silver-haired, Dr Frost appeared to be holding court with four female mourners who were whispering and giggling. I wondered if my colleague, and rival, Annabel Lake – ‘I don’t do funerals’ – knew her boyfriend was such a lothario.

One buxom woman, sixty-five-year-old Mrs Florence J. Tossell, was literally pawing at his jacket. Another pensioner, the rotund Mrs Ruth M. Reeves, slipped something into her handbag – a telephone number, perhaps – and then scurried past me with mischief written all over her face. I watched her rejoin her husband, John L. Reeves, who sported a spectacular walrus moustache, at the front gate. I couldn’t hear what he said but he grinned and she actually looked over and winked at me!

Coming from the industrial north, I just didn’t understand these country ways. Women, openly flirting in front of their husbands – and at a funeral!

Hawk-nosed Reverend Whittler swept to my side to await the funeral cortege. Seeing my look of surprise, he said, ‘I’m stepping in for Pastor Green. He’s snowmobiling in Utah. I’m thinking of a trip myself. Are you joining us for the service today?’

I was about to say no – I preferred my own method of communicating with the Lord – when my heart plunged into my boots.

Steve Burrows was turning into the church gate and I had absolutely no escape.

Steve was Gipping Hospital’s paramedic, and we first met at the scene of a fatal motorbike accident and, ever since then, he’d become infatuated and oblivious to my lack of interest. I’d been bombarded with flowers, cards, and emails, begging for just ‘one chance.’

Even though I tried to hide behind Whittler’s cassock, Steve saw me.

His face lit up. ‘Vicky!’ he cried, waving frantically. ‘Save me a seat!’

Even though it seemed everyone heard, I pretended I hadn’t and, with a hurried ‘See you in there, Vicar,’ darted inside.

The church was filling up quickly. I saw a packed pew with an empty seat behind a pillar. Ignoring the cries of pain as I trampled on toes, and ‘You won’t see anything behind there, dear,’ I scrambled over laps to the far end and dropped to my knees in fervent prayer.

Out of the corner of my eye, I watched Steve stop at the end of my pew, trying to attract my attention – ‘Psst! Psst!’ – before being swept along by a tidal wave of ladies from the Women’s Institute.

I felt a pang of guilt. With his pink cherubic face, sparkling blue eyes, and closely cropped blond crew cut, Steve wasn’t unattractive. Even the fact that he weighed at least two hundred and fifty pounds didn’t really bother me – Dad was often described as a ‘big man’. Steve wasn’t my type and I resented the way he refused to take no for an answer.

I sat back in my seat. It was true. I couldn’t see anything in front of me, but I could certainly smell something: boiled cabbages.

Looking over my shoulder, I was surprised to see Barry Fir, owner of the organic pick-your-own shop, and his four children holding scarves over their noses. Behind them, alone in the last row, sat Ronnie Binns.

Another person to avoid, I thought wearily. Recently promoted to Chief Garbologist under Gipping County Council’s restructuring program, Ronnie had taken the new EU recycling rules to heart. In fact, he’d become positively tyrannical and was slapping fines and threatening court orders to all and sundry.

Over the past few weeks, Ronnie had been begging the Gazette to run a recycling competition and naturally, the task of organizing it fell to yours truly. Catching my eye, Ronnie went through an intricate mime that, to my relief, seemed to imply he had more dustbins to empty and that he’d call me later.

As the organist played the opening chords of a farming favourite, ‘We Plow the Fields and Scatter’, hymn number two hundred and ninety from Hymns Ancient and Modern, New Standard, we all got to our feet and sang our hearts out.

Slowly, the pallbearers and coffin drifted by, followed by the immediate family.

I recognized rail-thin Mary F. Berry, the grieving widow, but was surprised to see her accompanied by Mrs Eunice W. Pratt. Of course! She was Gordon Berry’s sister! Apart from Eunice Pratt sporting her trademark lavender-coloured perm, the two women wore identical matching navy wool coats and wide-brimmed hats.

Eunice Pratt was a born troublemaker. Even our sixty-something man-mad receptionist, Barbara Meadows, who usually liked everyone, made herself scarce whenever Eunice Pratt came to the office brandishing one of the many petitions she insisted were destined for front-page publication. Eunice Pratt’s latest campaign was to ban floodlighting of buildings to reduce ‘energy use, carbon dioxide emissions, and light pollution’. She’d even written to the prime minister in Number 10, Downing Street.

Unfortunately, Eunice Pratt’s eye caught mine as she passed by. Instead of the usual sneer I’d come to expect, she seemed worried and mouthed the words ‘I must speak with you.’

It was at times like this I realized the importance of the country funeral. Here, among the living and the dead, pulsed the heart of the local community. These readers were my people. They looked to me to share their troubles as well as their joys.

After a handful of eulogies it was time to go to the cemetery and from there on to the social club. Originally, I’d hoped to accompany Topaz, but she got all snooty about being seen talking to the press, claiming ‘her kind never fraternized with the papers’, which I thought was a bit rich, coming from Miss I-want-to-be-a-reporter. In fact, her la-di-dah attitude really bothered me. It was as if she was a different person. Dad was right when he said, ‘There’s them, and then there’s us.’ Here, in Devon, the class system was very much alive.

As everyone trooped out of the church chattering, ‘lovely service . . . nice hymns . . . hideous hat . . .’ I fell to my knees once more, and hoped Steve wouldn’t loiter. No such luck. He waited patiently for me to finish. With a loud ‘Amen’ I got to my feet and said, ‘Please don’t talk to me, I’m too upset.’

Taking my arm, Steve led me to join the mourners at the graveside. A north wind whipped around the gravestones and sent hats skittering along the brick path. I couldn’t see Topaz. Having paid her respects, she must have slunk back to the café.

Luckily, Whittler was renowned for quickie burials and within minutes, the mourners were heading for their cars or making the ten-minute walk down Bridge Street to the Plym Valley Farmers Social Club.

‘Thanks, Steve,’ I said. ‘Must go now. Bye.’ Please, God, don’t let Steve come to the social club.

‘I’ve got to get back to work, doll,’ Steve said. Prayer works! Who needs sermons? ‘But I insist on escorting you to the club first.’

‘I’m fine.’

Steve shook his head vigorously. ‘My girl is not walking alone when she’s so upset.’

Steve took my arm again as if my mental grief had spread to my body. ‘Take it easy now, doll. One step at a time.’ We set off at a snail’s pace. The party would be over if we didn’t get a move on.

‘Actually, Steve, thanks to you, I feel better already.’

‘You can thank me tonight. Dinner. Seven thirty.’

‘I’m sorry but—’

‘It’ll cheer you up.’ Steve gave me a playful nudge. ‘You can’t spend the evening moping and all that praying won’t bring him back. He’s gone, doll.’

I was about to turn him down again, when I experienced a flash of genius. As a paramedic, Steve would have been first on the scene of any accident and had probably been called to the Berry tragedy. Who knew what he might have seen!

‘Dinner’s out, but how about a cup of tea?’ I said. ‘I’m thinking about doing a piece on fatal accidents in the farming community.’ This was true, I was. ‘Thought you might have seen a few in your time.’

‘Happy to, doll, but only over dinner. Wait a minute . . .’ Steve frowned. ‘You’re talking about Gordon Berry – God rest his soul – aren’t you?’

‘Yes. I thought I’d start with him.’

‘I got there about half an hour after old Berry went down.’ Steve shook his head. ‘Something fishy about it all, if you ask me.’

‘Why do you say that?’ I said sharply.

Steve grinned. ‘Have dinner with me, and I’ll tell you everything.’

Blast! How infuriating. If I wanted to find out what Steve knew, I didn’t really have a choice. I’d be friendly and professional. If Steve got fresh, I’d remind him that I never mixed business with pleasure.

‘Lovely,’ I said through gritted teeth. ‘But let’s meet at the restaurant.’ Mum always claimed that if a man picked you up, payment was a goodnight kiss. I didn’t fancy grappling with Steve in his car. ‘Where are we going?’

‘It’s a surprise,’ said Steve. ‘What’s your address? I insist on picking you up.’

I’d never met anyone so determined to have his way. ‘Number twenty-one, Factory Terrace, Lower Gipping – and I can’t be late back because—’

‘Millicent and Leonard Evans’s place? Sadie Evans’s folks?’ Steve stopped in the street. He looked me up and down, gawking. ‘Well, I’ll be blowed!’

I smiled politely. It seemed everyone knew about Sadie Evans, Gipping’s only pole dancer who fled to Plymouth in a cloud of scandal. I’d never met her, but whenever I had to give my new address, the reaction was always the same – hope and lust. It was as if by sleeping in Sadie’s single bed, I must inherit her louche qualities. I’d soon set Steve straight.

‘I don’t know her,’ I said. ‘In fact, I have no idea what she’s like, do you?’

When Steve didn’t answer I saw his mood had changed. It was as if the tide had gone out and he was carrying the weight of the world on his shoulders.

‘Are you all right?’ I said.

‘We’re here,’ Steve said quietly. Someone had thoughtfully marked the entrance to the Plym Valley Farmers Social Club by tying three black balloons to a bale of straw on the pavement. ‘I’d better get back.’

Without so much as a ‘looking forwards to seeing you later’, Steve turned on his heel and walked away.

‘Are we still on for seven thirty?’ I heard myself shout out.

Steve did a dismissive backwards hand gesture. Presumably that meant yes.

I watched him disappear around the corner thoroughly puzzled. Had I said something wrong? Maybe he was so infatuated with me he found it difficult to say goodbye?

Either way, it looked like I was going to be in for a very long evening ahead.

Plym Valley Farmers Social Club occupied the two floors above J. R. Trickey & Associates, Gipping’s solicitors. Built in the late 1800s, the house was formerly a private home. Access was via a dark-blue door next to the glass-fronted bay window. Today, the door stood open. A large sign declared HEDGE-JUMPERS NOT WELCOME.

Excellent! Jack Webster might be on to something with his jumpers’ theory.

I climbed the narrow wooden stairs to the first floor that had been converted into an open-plan meeting area. A long wooden bar stretched the length of the room with a kitchenette in the front. Wooden tables and chairs were scattered throughout. There was a small pool table and the usual board games available – darts, dominoes, chess, and shove ha’penny. On the second floor were two sitting rooms, an office, and a unisex toilet.

Only five years ago, women had been banned from the club. Eunice Pratt had engineered one of her petitions citing equal rights for women. She enlisted her friends from the Women’s Institute and persuaded them to dress up as suffragettes. They had chained themselves to the railings outside the Magistrates Court and after a huge battle with the farmers, many of whom they were married to, emerged victorious.

A delicious-looking finger buffet was laid out in the meeting room with the standard fare of assorted sandwiches, sausage rolls, and salmon pinwheels. The new owner of Cradle to Coffin Catering, fiftysomething Helen Parker, liked to pass the food off as homemade, but I knew it came from Marks & Spencer. On one of my rare trips to the bright lights of Plymouth, I spotted her loading up her shopping trolley. She begged me to keep her secret and, of course, I agreed. Who am I to judge? Besides, Dad says, ‘It’s always handy to have something on someone.’

I was starving. Loading up my paper plate with goodies, I took an empty seat in the corner to watch the proceedings. As the mourners poured in, I mentally ran through a list of tactful, but leading, questions running from Gordon Berry’s eyesight to who might want him dead.

Jack Webster, a ruddy-complexioned man in his fifties, waved me a greeting from the door. This was encouraging! He obviously wanted to talk to the press!

Leaving my plate of food on the chair, I hurried towards him, notebook in hand.

‘Morning, Mr Webster,’ I said. ‘I’m sure—’

‘This is a funeral, Vicky,’ he said curtly. ‘Hardly suitable for an interview. Excuse me.’

Stung, I stepped aside. Jack Webster strode towards the corpulent figure of Eric P. Tossell, who welcomed him with a pint of Guinness and a hearty backslap. Obviously, Jack Webster’s wave had not been intended for me.

Thoroughly rebuffed, I retreated to my chair. For now, I’d have to content myself with keeping my eyes and ears open.

Standing by a roaring log fire, Mary Berry and Eunice Pratt chatted to the other wives while the men congregated along the bar, pints in hand. As the alcohol flowed, conversations got louder. Someone suggested a game of darts.

Even though I needed to have a quiet word with the widow, I realized that the Plym Valley Farmers Social Club might not be conducive to sympathetic, probing questions – as I’d just discovered. In fact, since Devon scrumpy and Harveys Bristol Cream sherry always flowed so liberally, the Gazette had had to print apologies on more than one occasion over a quote taken, allegedly, out of context. I always preferred a home visit anyway because I usually got fed.

As I polished off the last cucumber sandwich, I noticed Dr Frost sauntering over to the group of ladies who seemed to be swapping recipes. In a flash, Eunice Pratt shot him a filthy look, grabbed her sister-in-law’s arm, and propelled her in my direction, declaring in a loud voice, ‘Disgusting man!’

‘Hello, Mrs Pratt.’ I jumped to my feet, adopting the smile I use for people I can’t stand.

‘Something must be done about that doctor!’ she said.

‘Hush, Eunice dear. It’s just harmless fun.’

‘Harmless?’ Eunice Pratt snorted and turned to me, arms akimbo. ‘That man is coming between husband and wife. There’ll be trouble. Mark my words.’

‘Eunice, please!’

‘Would you like to sit down?’ I pulled out two chairs while stealing a glance at Dr Frost, who was now seated with Florence Tossell on one knee and Ruth Reeves – struggling to keep her balance – on the other.

True, with his shock of silver-white hair, he was definitely handsome for a man in his forties. Annabel certainly thought so, and no doubt Eunice Pratt was just plain jealous because he wasn’t paying her any attention. Rumour had it that her husband went off on a business trip in 1973 and never returned.

‘Thank you, Vicky dear.’ Mrs Berry sank down gratefully. ‘I was up at four milking this morning. Gordon may be gone but –’ she gave a brave smile ‘– life goes on.’

I recalled Pete Chambers, our chief reporter, and his strict criteria for front-page glory: Facts! Evidence! Photos! A snap of Mrs Berry farming alone would do nicely. ‘I was thinking of popping in tomorrow morning to ask some questions for the obituary,’ I said.

‘Good,’ said Eunice Pratt. ‘I hope you’re going to tell her, Mary.’

A voice called out, ‘One hundred!’ Another yelled, ‘Jammy bugger!’ There was a round of applause.

‘Tell me what?’ I said.

Mrs Berry looked unhappy. ‘It’s nothing.’

‘If you won’t say, I will.’ Eunice Pratt paused and took a deep breath. ‘Gordon was murdered.’

‘Murdered?’ I cried. Hurrah! So my instincts were right! ‘Didn’t the coroner return a verdict of accidental death?’

‘He only saw poor Gordon’s body back at the morgue,’ Eunice Pratt declared. ‘That dreadful Dr Frost was called to the scene. He said it wasn’t necessary to call the police.’

It was a good thing I’d agreed to have dinner with Steve tonight, after all.

‘Dr Frost said it was a freak accident,’ Mrs Berry said. ‘And it was.’

‘Say what you like, but I know my brother,’ Eunice Pratt cried. ‘He told us he was cutting Honeysuckle Lane that morning, but they found him at Ponsford Cross!’

‘I don’t want any trouble,’ Mrs Berry mumbled. ‘I don’t want to be thrown out into the cold.’

‘Gordon only had Dairy Cottage for his lifetime,’ Eunice Pratt went on. ‘With him gone, what happens to us? She can’t farm the place by herself. Look at her!’ Time had not been kind to Mrs Berry. She definitely looked three score and ten. ‘And don’t look at me. I can’t do it. I’ve got a bad back.’

. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...