ONE

May 20

I am afraid.

Someone is coming.

That is, I think someone is coming, though I am not sure, and I pray that I am wrong. I went into the church and prayed all this morning. I sprinkled water in front of the altar, and put some flowers on it, violets and dogwood.

But there is smoke. For three days there has been smoke, not like the time before. That time, last year, it rose in a great cloud a long way away, and stayed in the sky for two weeks. A forest fire in the dead woods, and then it rained and the smoke stopped. But this time it is a thin column, like a pole, not very high.

And the column has come three times, each time in the late afternoon. At night I cannot see it, and in the morning it is gone. But each afternoon it comes again, and it is nearer. At first it was behind Claypole Ridge, and I could see only the top of it, the smallest smudge. I thought it was a cloud, except that it was too gray, the wrong color, and then I thought: there are no clouds anywhere else. I got the binoculars and saw that it was narrow and straight; it was smoke from a small fire. When we used to go in the truck, Claypole Ridge was fifteen miles, though it looks closer, and the smoke was coming from behind that.

Beyond Claypole Ridge there is Ogdentown, about ten miles farther. But there is no one left alive in Ogdentown.

I know, because after the war ended, and all the telephones went dead, my father, my brother Joseph and Cousin David went in the truck to find out what was happening, and the first place they went was Ogdentown. They went early in the morning; Joseph and David were really excited, but Father looked serious.

When they came back, it was dark. Mother had been worrying—they took so long—so we were glad to see the truck lights finally coming over Burden Hill, two miles away. They looked like beacons. They were the only lights anywhere, except in the house—no other cars had come down all day. We knew it was the truck because one of the lights, the left one, always blinked when it went over a bump. It came up to the house, and they got out; the boys weren’t excited anymore. They looked scared, and my father looked sick. Maybe he was beginning to be sick, but mainly I think he was distressed.

My mother looked up at him as he climbed down.

“What did you find?”

He said: “Bodies. Just dead bodies. They’re all dead.”

“All?”

We went inside the house where the lamps were lit, the two boys following, not saying anything. My father sat down. “Terrible,” he said, and again, “terrible, terrible. We drove around, looking. We blew the horn. Then we went to the church and rang the bell. You can hear it five miles away. We waited two hours, but nobody came. I went in a couple of houses—the Johnsons’, the Peters’—they were all in there, all dead. There were dead birds all over the streets.”

My brother Joseph began to cry. He was fourteen. I think I had not heard him cry for six years.

May 21

It is coming closer. Today it was almost on top of the ridge, though not quite, because when I looked with the binoculars I could not see the flame, but still only the smoke—rising very fast, not far above the fire. I know where it is: at the crossroads. Just on the other side of the ridge, the east-west highway, the Dean Town Road, crosses our road. It is Route Number 9, a state highway, bigger than our road, which is County Road 793. He has stopped there and is deciding whether to follow Number 9 or come over the ridge. I say he because that is what I think of, though it could be they or even she. But I think it is he. If he decides to follow the highway, he will go away, and everything will be all right again. Why would he come back? But if he comes to the top of the ridge, he is sure to come down here, because he will see the green leaves. On the other side of the ridge, even on the other side of Burden Hill, there are no leaves; everything is dead.

There are some things I need to explain. One is why I am afraid. Another is why I am writing in this composition book, which I got from Klein’s store a mile up the road.

I took the book and a supply of ball-point pens back in February. By then the last radio station, a very faint one that I could hear only at night, had stopped broadcasting. It had been dead for about three or four months. I say about, and that is one reason I got the book: because I discovered I was forgetting when things happened, and sometimes even whether things happened or not. Another reason I got it is that I thought writing in it might be like having someone to talk to, and if I read it back later it would be like someone talking to me. But the truth is I haven’t written in it much after all, because there isn’t much to write about.

Sometimes I would put in what the weather was like, if there was a storm or something unusual. I put in when I planted the garden because I thought that would be useful to know next year. But most of the time I didn’t write, because one day was just like the day before, and

sometimes I thought—what’s the use of writing anyway, when nobody is ever going to read it? Then I would remind myself: sometime, years from now, you’re going to read it. I was pretty sure I was the only person left in the world.

But now I have something to write about. I was wrong. I am not the only person left in the world. I am both excited and afraid.

At first when all the others went away, I hated being alone, and I watched the road all day and most of the night hoping that a car, anybody, would come over the hill from either direction. When I slept, I would dream that one came and drove on past without knowing I was here; then I would wake up and run to the road looking for the taillight disappearing. Then the weeks went by and the radio stations went off, one by one. When the last one went off and stayed off, it came to me, finally, that nobody, no car, was ever going to come. Of course I thought it was the batteries in my radio that had run down, so I got new batteries from the store. I tried them in the flashlight and it lit, so I knew it was really the station.

Anyway, the man on the last radio station had said he was going to have to go off; there wasn’t any more power. He kept repeating his latitude and longitude, though he was not on a ship, he was on land—somewhere near Boston, Massachusetts. He said some other things, too, that I did not like to hear. And that started me thinking. Suppose a car came over the hill, and I ran out, and whoever was in it got out—suppose he was crazy? Or suppose it was someone mean, or even cruel, and brutal? A murderer? What could I do? The fact is, the man on the radio, toward the end, sounded crazy. He was afraid; there were only a few people left where he was and not much food. He said that men should act with dignity even in the face of death, that no one was better off than any other. He pleaded on the radio, and I knew something terrible was happening there. Once he broke down and cried on the radio.

So I decided: if anyone does come, I want to see who it is before I show myself. It is one thing to hope for someone to come when things are civilized, when there are other people around, too. But when there is nobody else, then the whole idea changes. This is what I gradually realized. There are worse things than being alone. It was after I thought about that, that I began moving my things to the cave.

May 22

The smoke came again this afternoon, still in the same place as yesterday. I know what he (she? they?) is doing. He came down from the north. Now he is camping in that spot, at the crossroads, and exploring east and west on Number 9, the Dean Town Road. That worries me. If he explores east and west he is sure to explore south, too.

It also lets me know some things. He is sure to be carrying some fairly heavy supplies and equipment. He leaves these at the crossroads while he makes side trips, so he can go faster. It also means he probably hasn’t seen anyone else along the way, wherever he came from, or he wouldn’t leave his stuff. Or else he has somebody with him. Of course he could be just resting. He might have a car, but I doubt that. My father said that cars would stay radioactive for a long time—because they’re made of heavy metal, I suppose. My father knew quite a lot about things like that. He wasn’t a scientist, but he read all the scientific articles in the newspapers and magazines. I suppose that’s why he got so worried after the war ended when all the telephones went off.

The day after they took the trip to Ogdentown, they went again. This time they went with two cars, our truck and Mr. Klein’s, the man who owned the store. They thought that was better, in case one broke down; Mr. Klein and his wife went, too, and finally Mother decided to go. I think she was afraid of being separated from my father; she was more worried than ever after she heard what happened in Ogdentown. Joseph was to stay at home with me.

This time they were going south, first through the gap to where the Amish lived to see how they had come through the bombing. (Not that they had been bombed—the nearest bombs had been a long way off; Father thought a hundred miles or more; we could hardly hear the rumble, though we felt the earth shake.) The Amish farms were just south of our valley. The Amish were friends of ours and especially of Mr.

Klein’s, being the main customers at his store. Since they had no cars but only horses and wagons they did not often drive all the way to Ogdentown.

Then, after they saw the Amish they were going to circle west and join the highway to Dean Town, passing through Baylor on the way. Dean Town is a real city—twenty thousand people, much bigger than Ogdentown. It was to Dean Town I was supposed to go year after next, to the Teachers’ College. I am hoping to be an English teacher.

They started out early in the morning, Mr. Klein leading the way in his panel truck. My father put his hand on my head when they left, the way he used to when I was six years old. David said nothing. They had been gone about an hour when I discovered that Joseph was nowhere to be found, and I figured out where he was: hidden in the back of Mr. Klein’s truck. I should have thought of that. We were both afraid of being left behind, but my father said we should stay, to water the animals and to be here in case somebody came, or in case they got the telephones going again and ours should ring. Well, it never rang, and nobody came.

My family never came back, and neither did Mr. and Mrs. Klein. I know now there weren’t any Amish, nor anybody in Dean Town. They were all dead, too.

Since then I have climbed the hills on all sides of this valley, and at the top I have climbed a tree. When I look beyond, I see that all the trees are dead, and there is never a sign of anything moving. I don’t go out there.

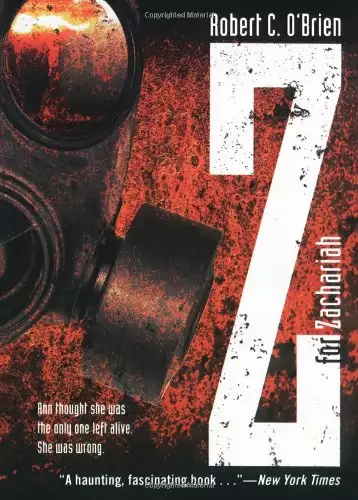

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved