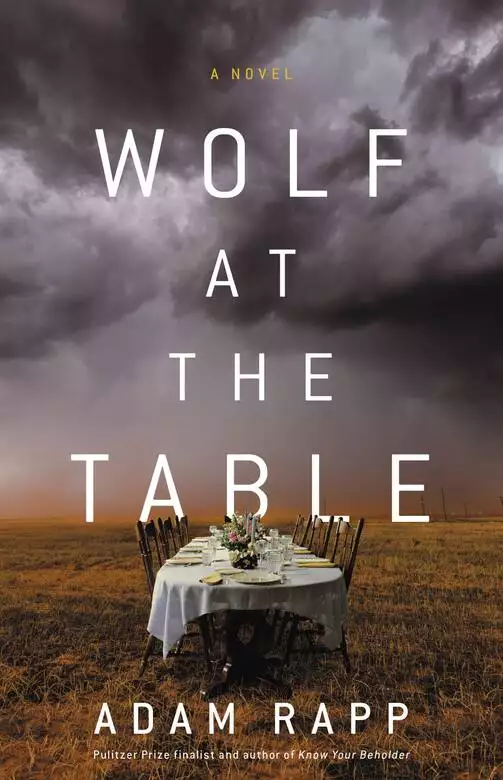

Wolf at the Table

- eBook

- Audiobook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

The Corrections meets We Need to Talk About Kevin in this harrowing multigenerational saga about a family harboring a serial killer in their midst, from the Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award finalist playwright Adam Rapp.

As late summer 1951 descends on Elmira, New York, Myra Larkin, thirteen, the oldest child of a large Catholic family, meets a young man she believes to be Mickey Mantle. He chats her up at a local diner and gives her a ride home. The matter consumes her until later that night, when a triple homicide occurs just down the street, opening a specter of violence that will haunt the Larkins for half a century.

As the siblings leave home and fan across the country, each pursues a shard of the American dream. Myra serves as a prison nurse while raising her son, Ronan. Her middle sisters, Lexy and Fiona, find themselves on opposite sides of class and power. Alec, once an altar boy, is banished from the house and drifts into oblivion. As he becomes an increasingly alienated loner, his mother begins to receive postcards full of ominous portent. What they reveal, and what they require, will shatter a family and lead to devastating reckoning.

Through one family’s pursuit of the American dream, Wolf at the Table explores our consistent proximity to violence and its effects over time. Pulitzer Prize finalist Adam Rapp writes with gorgeous acuity, cutting to the heart of each character as he reveals the devastating reality beneath the veneer of good society.

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Wolf at the Table

Adam Rapp

The reader’s name is Myra Lee Larkin and she is in love with the story’s narrator, a restless, opinionated, at times foulmouthed young man named Holden, who, at sixteen, has just run away from his boarding school in Agerstown, Pennsylvania, a fictional town that Myra imagines being located due south of Elmira, just on the other side of the state line. Holden has been expelled and leaves on a Saturday, after a football game with a rival academy, just before Christmas break, rather than on the following Wednesday, the official beginning of winter recess, when his parents are expecting him. After an awkward visit with the only professor whom he felt obliged to bid farewell, Holden takes a train to New York City. As he peers out the window of the eastern Pennsylvania landscape as his train hurtles toward Manhattan, there is the sense that his life will be forever changed. Myra Lee Larkin briefly peers out the small window beside her booth, hoping that her life will someday include similar adventure.

There are three others seated in the small chromium-trimmed diner. Two booths in front of Myra, an old man looks down at a plate of scrambled eggs as if it will provide a solution to the quandary of his life, while in the booth closest to the entrance sits a plump, overly made-up woman whose hair is arranged like a swirling pastry. At the counter slouches a handsome older blond boy smoking a cigarette and drinking a cup of coffee.

Myra holds the book with her thin, pale hands as if clutching a thing that should never be dropped, so transfixed that she isn’t even aware of the black fly buzzing around her food. She’ll often order a grilled cheese sandwich and a malted milk, which she pays for with her weekly allowance. She can always read up to fifteen or twenty pages during her visit to the diner. Myra tries her best not to read too quickly, but sometimes the words start to tumble and the voice of her narrator gallops in her head as if to overwhelm her and she has to force her eyes away from the page to calm herself.

At thirteen, she is the oldest of the six Larkin children and her mother always grants her this free time after the five o’clock Mass as long as she’s home by seven fifteen sharp to help with her baby brother, Archie. Following the service she makes a beeline west toward the little diner in her white saddle shoes, which, after re-soling, will be handed down to her sister Fiona, who will be twelve in October, only sixteen months younger than Myra but two grades behind her in school. Myra can’t flee the church parking lot fast enough. She even holds her breath so she won’t inhale the gravel dust.

Her mother has no idea that her daughter is reading this purportedly scandalous novel, which has been secreted into a makeshift cardboard slot rigged with duct tape to the underside of the table at this booth. The head waitress, Ethel, with her Jean Kent hair and knowing eyes, has become a kind of shepherd to the book’s safekeeping. Last Sunday the corner booth was already occupied by a pair of Irish nuns, who drank cup after cup of coffee, but Ethel made sure to deliver the book to Myra—under the plate containing her usual Grilled Cheese Deluxe—with a conspiratorial wink. Myra always makes sure to tip Ethel at least a quarter.

For the past few weeks, Myra has been composing letters to Holden in her diary. In her looping, careful penmanship she dutifully writes to him about Elmira; about its long winters and insufferable summers and the rotten-egg stink of the Chemung River and her dream of someday going to New York City. She’s even sketched a few pictures for him: her tall mother with her thick nest of black hair and the Larkins’ Siamese cat, Frank, and the bedroom desk where she does her homework (and composes letters to him) and her brother Alec with his crooked bangs and mischievous dark eyes. Myra has never considered herself to be much of an artist, but she likes to draw, and more than that, she likes to share the images of her life with Holden. Although the letters will, of course, never be sent or receive a response, for her they feel as real as anything she’s ever sealed in a stamped envelope and delivered to the post office.

She looks up from her book to find the blond boy from the counter sitting across from her. In the novel, Holden’s train has just pulled into Penn Station and Myra is anxious to know what happens next. She doesn’t want to put the book down but elects to do so out of politeness.

“You gonna eat that?” the boy says, pointing to her grilled cheese sandwich.

Myra hadn’t even noticed him walk over and she’s a little shocked by his sudden proximity. And by his handsomeness. He has light blue eyes and a strong chin and his hair is parted on the side in the style of Montgomery Clift. Myra has never seen this boy before, certainly not at Holy Family Jr. High, at church, or anywhere else in Elmira for that matter. He wears a short-sleeve plaid shirt and tan trousers.

“I’d be happy to help you out,” he offers, still staring at her plate.

She nods and he takes half of the grilled cheese and bites into it. The muscles in his jaws dance and pulse. He breathes noisily through his nose. She pushes her malted milk toward him and he gulps from it. He thanks her and wipes his mouth with the back of his hand. Unlike other boys his age, who usually have pimples or blemishes where they’ve nicked themselves shaving, his skin is clear.

“What are you reading?” he asks.

Myra shows him the novel’s spine.

“Interesting title,” he says. “What’s it about?”

“This boy who’s running away from his boarding school,” she says. “Well, he actually got kicked out for failing four subjects, but he’s leaving before he’s supposed to. He’s pretty confused but there’s something about him.”

“Everyone’s always running from something,” the boy says. “You live around here?”

“I live over on Maple Avenue,” she says, “which is about a mile and a half from here.”

“I’m not familiar with that part of town,” the boy says. “What’s your name?”

Myra has a momentary instinct to lie and offer one of her sisters’ names but for some reason she can’t. “Myra,” she says, in a voice that sounds strange and far away.

“Pleased to meet you, Myra. I’m Mickey.” He reaches across the table and extends his hand.

She accepts it and they shake in a businesslike manner. His hand is strong and callused and there are little soft blond hairs sprouting along his wrist and forearm. Myra is struck by how safe his hand makes her feel. After retracting hers, she takes a bite out of the other half of the grilled cheese and drinks from the malted milk, just to have something to do.

“I’ll bet you’ve lived in Elmira your whole life,” the boy says. “Ever been anywhere else?”

“I’ve been to the Catskills to visit family,” she says. “Do you travel?”

“Oh, I love traveling,” he says. “I’ve been all over the country. I’ve seen the Grand Canyon, the Mojave Desert, and the Pacific Ocean. I’ve even been to Washington State.”

“Where are you from?”

“I’m originally from a small town in Oklahoma,” he replies, “but I consider myself to be a genuine citizen of the world.”

Ethel appears at the booth. “Your check, honey,” she says. She scribbles on her pad and drops the check on the table. Myra thanks her and opens her pocketbook.

“Yours is over on the counter,” Ethel tells the boy.

“Thank you,” he says.

Ethel stands there, smiling, her arms folded, until he takes the hint, excusing himself and heading back to the counter, where he reaches into his front pocket, produces a few coins, and drops them beside his coffee cup.

“Was he being funny with you?” Ethel quietly asks through the side of her mouth.

“No,” Myra says, “he’s nice.”

The older boy opens the door to exit the diner. “Have a good evening, ladies,” he calls over his shoulder.

A FEW BLOCKS AFTER Myra begins the mile-and-a-half journey home it starts to pour. The crickets were loud on her way into church, and the rain comes as no surprise. The raindrops, as big and round as coins, splat on the sidewalk. Myra shelters under the awning of the Fanny Farmer Candy Store, which is currently closed. She knows she should keep walking or she won’t make it home in time to help her mother with Archie but she stays put, hoping the storm will pass.

Moments later a yellow Chevy Bel Air with whitewall tires and Pennsylvania license plates pulls up beside her. The boy from the diner is at the wheel.

He lowers the window. “Looks like you could use a ride,” he says.

Myra hesitates. Something tightens the bones in her chest. The rain is really coming down now.

“This storm’s only gonna get worse,” the boy says.

The color of his car brings out the blond in his hair. Even in the dim, overcast light his eyes seem so blue.

Myra’s bladder feels weak, as if she could go right there in front of the candy store. “Okay,” she hears herself say. She emerges from under the awning and jogs around to the passenger’s side.

Myra has never gotten this kind of attention from any boy, let alone an older, handsome high school boy. During the seventh grade she would often catch Ralph Namie, a quiet eighth-grader with the unfortunate, unformed face of a scarecrow, staring at her in the cafeteria, but that’s about it. One of her girlfriends, Emily Kerr, has already started messing around with boys. She even talks about going all the way with a high school sophomore named Charles Wilkes. But to Myra that kind of thing still seems a long ways off.

Her new friend drives nonchalantly, with one hand on the wheel and the other in his lap. The Bel Air’s windshield wipers squeal across the glass.

“Where to?” the boy asks.

“Home,” she says, and directs him toward Maple Avenue.

It usually takes her thirty minutes to walk; by car it should take only five or ten. They pass by the houses of Elmira, many of which are thin, two-story, colorless homes jammed together, their flat roofs a bit lopsided. But after a half mile or so they happen upon a series of vast, palatial Victorians with their conical attic dormers and wide lots.

“Are you in high school?” Myra finally asks.

“Me?” the boys replies. “I’m past all that.”

She asks how old he is and he tells her that he’s nineteen. “Are you enrolled in college?” she says.

No, he says, he already has a job.

“Doing what?” she asks.

“I play right field for the New York Yankees,” he says.

“You’re on the Yankees?” Myra practically squawks.

“Scout’s honor,” he says.

She wants to believe him but it just seems so improbable. In the car on the way to church Myra heard about the Yankees’ day game. As the Larkins pulled into the parking lot of St. John the Baptist, the radio announcer was reporting the results.

“Didn’t you have a game today?” she asks.

“We did have a game,” Mickey says. “Got our tails kicked in by the Philadelphia Athletics. Fifteen to one. Right in Yankee Stadium, too, in front of the home crowd. It was downright embarrassing.”

“How did you get up to Elmira so fast?”

“Oh, I’m not with the team right now,” he says.

“Why not?”

“They sent me back down to the minor leagues in July. I fell into a bit of a batting slump so I got demoted. I had to report to their Triple-A affiliate to work the kinks out.”

Myra is simply amazed.

“I love playing the outfield,” he continues. “One of my favorite things to do before a game—before I head into the locker room to put my uniform on—is to take my shoes and socks off and walk barefoot through the grass of Yankee Stadium. They mow it so perfectly and you can feel a softness coming up between your toes. But you can also feel a wildness, too. All the secrets of the earth hidden in the soil.”

Myra imagines him walking through the outfield grass in Yankee Stadium, holding his shoes and socks, the cuffs of his trousers rolled up to his calves.

“I’m s’posed to be in Kansas City but I got a coupla days off so I thought I’d take a drive, clear my head. I love this part of the country.”

Myra directs him to turn left onto Maple Avenue. “It’s only four more blocks,” she says.

They are quiet for the rest of the drive. The rain has thinned but there is a roll of thunder. Myra can’t quite believe she’s getting a ride home from a genuine New York Yankee. Who would believe her? When they arrive at her house the boy pulls the car over on the other side of the street and shifts into park. As the Bel Air idles Myra can feel him looking at her. It’s as if she’s being leered at by an animal and she knows she should be afraid but she feels strangely calm. She’s already late, but not by more than a few minutes. If she were smart she would get out of the car and go inside and help her mother, but she finds herself unwilling to move.

“I like talking to you,” Mickey finally says.

Myra’s cheeks fill with heat.

“Do you like talking to me?” he asks.

“Yes,” she hears herself say.

“Would you like to continue our conversation?” he says.

“Okay,” she replies. “But my mother might come out here if she sees me in your car.”

“Where should we go?” he asks.

She tells him about a nearby park and the boy shifts the car into gear, and five minutes later they enter a large green dotted with trees. He parks under a weeping willow, whose heavy, soaked catkins graze the windshield. After Mickey turns the engine off Myra’s senses sharpen. She can smell the car’s leather upholstery, its rich, nutmeggy calfskin. The cool ozone from the storm slips in through the crack in her window. The rain has settled into a steady simmer.

Mickey turns the radio on to Patti Page’s “The Tennessee Waltz.”

I was dancing with my darling to the Tennessee waltz

When an old friend I happened to see…

It might be the saddest, most romantic song Myra has ever heard.

“How old are you?” Mickey finally asks.

“I just turned thirteen in June,” she says.

“June what?”

“June fifteenth,” she says. “I’m a Gemini.”

“I was an October baby,” Mickey says. “October twentieth.”

“That makes you a Libra,” Myra says.

“What exactly is a Libra?” he says.

“In astrology it represents the scales of justice.”

“So that makes me a weight-measuring device?” he says. “How boring. I’d rather be a lion or a fish.”

They laugh and their laughter seems to mix well with the lilt of Patti Page’s voice.

From his pocket Mickey produces a ball of Dubble Bubble chewing gum, its wrapping wrinkled, and offers it to Myra.

“Oh, no thank you,” she says.

He sets the gum on the dash in front of her. “In case you change your mind,” he says. After a silence he adds, “You’re very pretty, Myra. I know that might be rude of me to say.”

She thanks him, feeling the heat again in her cheeks, which she has to resist hiding with her hands.

“I don’t meet many girls like you,” he says.

“Oh, I don’t believe that,” she says. “I’m not much to look at.”

“You are, though,” he says. “Those eyes of yours could do a lot of damage. Are they gray or green?”

“My mother says they’re hazel.”

“I noticed them as soon as I came over to your booth.”

Myra bites her lower lip to keep from smiling. She wishes she could somehow make her hazel eyes surge and put him under a deep spell.

“Do you have brothers and sisters?” he asks.

“Three sisters and two brothers,” she replies. “I’m the oldest.”

“Such a large family,” he says. He seems to consider something, intensely, for a moment, and then, under his breath, adds, “Too large,” and shakes his head.

“Too large for what?” Myra asks.

“Oh, I don’t mean nothin’ by it,” he says. “It just seems like it would be a lot to manage.”

“It is,” Myra says. “My sister Joan is mentally handicapped. She can dry the dishes but she’s not allowed near the silverware. Her mind is quite stunted. And I have a baby brother now, too, so my mother relies on me to help with the others.”

“How old is your baby brother?”

“Two months. A June baby, like me. His name is Archibald. We call him Archie. He can be very fussy but he quiets down after Mother feeds him.”

The new song on the radio is Perry Como’s “Hoop-Dee-Doo.” The rain hitting the passenger’s-side window seems to be momentarily in cahoots with the song’s jaunty polka rhythm.

“Tell me all their names,” Mickey says.

“Fiona, Alec, Joan, Lexy, and Archie. That’s everyone, in order. Sometimes Alec calls Joan ‘the Bullfrog.’ He can be mean.”

“And you’re Myra,” he says, smiling.

“The oldest,” she says.

His smile makes her imagine him brushing his teeth, washing his face, combing his hair, even peeing in the toilet. She shoves these images from her mind.

Another car enters the park and wheels past the Bel Air. Mickey watches the car keenly for a moment, craning his neck. He even rolls down the window partway. It’s still light out, but darker than usual because of the rain.

After he rolls the window back up he says, “Lincoln Cosmopolitan.”

“You like cars?” Myra asks.

“I do,” he says. “I prefer Chevrolet to Lincoln, though.”

“Yours is lovely,” Myra says, immediately embarrassed by her flattery. The words feel clumsy to her, as if she uttered them through a loose tooth.

Mickey doesn’t acknowledge the compliment and the two of them are quiet again. Only Perry Como on the radio. Myra feels a strange peace sitting with this older boy in his car. Might they drive away together? Might he take her back to Kansas City with him?

“Can I give you a picture?” he finally says.

“Of what?” she asks.

“Of me,” he says.

“… Okay,” Myra hears herself say, doing her best to hide her excitement. Her teeth nearly begin to chatter.

Mickey reaches into his back pocket and produces a billfold, from which he removes a small snapshot. He unfolds the black-and-white photo and hands it to her. Myra smooths it out on her lap. Staring back at her is a boy in a military uniform. He has taken a knee. His right hand clutches the snout of a rifle, its stock driven into the dirt. The boy wears camouflage fatigues and a combat helmet and he’s smiling proudly.

“That’s you?” Myra asks.

“It sure is,” he says. “Over in Osan, Korea.”

“It’s a lovely picture.”

“I want you to have it.”

She thanks him and secrets it away in her pocketbook. After she snaps it shut he asks her for a picture.

“I don’t have any with me,” Myra says.

“Will you send me one?”

“You’ll have to give me your address.”

“Just send it to me at Yankee Stadium.”

“What’s your last name?” she asks.

“Mantle,” the boy says. “On the envelope just write ‘Mickey Mantle, in care of Yankee Stadium, the Bronx, New York.’”

When he drops Myra off in front of her house he gives her a silver dollar.

“What’s this for?” Myra asks.

“For being you,” the boy says. “I’m tempted to flip it but I’ve already made my decision.”

“About what?” she says.

“About you,” he says, and winks at her.

She kisses him goodbye on the cheek. As she walks into her house she can still taste the faint salty tang of his skin.

“You’re thirty-five minutes late,” Ava Larkin tells her daughter as she enters the kitchen. Ava is rinsing a rag in the sink.

Myra looks at the clock over the stove and it’s true. “I got caught in the rain,” she lies.

“That’s a poor excuse,” her mother says. “Archie’s running a fever,” she adds, squeezing the water out of the rag. “I need you to make him a cold bath.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

At two months old, Myra’s baby brother still possesses the bald, wrinkled face of a stunned elderly police officer. Following church services, Ava likes to mill about the parking lot with the other mothers, baby Archie hoisted in her arms. Myra’s three sisters—Fiona, Joan, and Lexy—will busy themselves picking dandelions in St. John the Baptist’s front lawn. Fiona dutifully marshals four-year-old Lexy, keeping her close, while the heavyset, mentally slow Joan, who just turned seven, is content to stay in one place. Often she’ll happily sit cross-legged and stare at the church’s ancient sugar maple as if it will someday bestow upon her a great secret.

Ava and the other mothers will gather around their Packards and Hudsons and Plymouth Cranbrooks and gossip about the teachers at Holy Family Junior High School, especially Sister Rose, who’s far too pretty to be a nun, and the water level of the Chemung River, and President Truman’s sourpuss wife, Bess, and the troops in South Korea, and how Steve and Myrtle McCrae’s boy, Cotter, just landed in Busan, and the Soviet Union and their dastardly atomic bomb, and the recent lightning storm that felled the Blubaughs’ copper beach tree over on South Magee Street, and how at least two gallons of whole milk from Houch’s Dairy went bad, and what about the new salesman at Triangle Shoes, doesn’t he look exactly like that handsome detective character from Where the Sidewalk Ends, the one played by Dana Andrews? They talk and smile and smoke their Old Golds, somehow indifferent to the hovering gnats.

At nearly six-three, Myra’s mother looms over her children like a creature in a fable. Donald Larkin, a head shorter than his wife, often stands beside her like some dutiful, ever-ready attendant. At thirty-two, despite having already given birth to six children, Ava is slender and pretty, with rich, youthful skin, and only a few strands of gray shooting through her boot-black hair. Myra admires her mother’s beauty, her steady poise, her physical strength.

After Myra fills the baby’s basin with cold water in the upstairs bathtub, she brings it down to the kitchen, where her mother is at the counter next to the icebox, cleaning the mess between Archie’s legs.

“Next Sunday there will be no free time following Mass,” Ava tells her. “You’ll remain at the church with your sisters. You can mix with the other children in the lawn and keep an eye on Joan.”

Myra nods. The disappointment of having that hour taken from her feels like a blow to the backs of her legs. How will she read her book? Holden’s train has just arrived at Penn Station and anything could happen. The thought of not having that time with him almost makes her sick, but she knows better than to argue.

Archie’s legs swim out as her mother wipes up the greenish, foul-smelling muck. Myra grabs a clean diaper from the compartment below the silverware drawer and sets it beside the basin.

“I need to be able to rely on you,” her mother tells her, unfolding the diaper.

“Yes, ma’am,” Myra says.

“I don’t enjoy taking your privileges away.”

“Yes, ma’am,” Myra repeats.

“You have to set the proper example for your sisters. I’m not sure if there’s much hope for Alec, but Fiona and Lexy have a real chance and they look to you.”

Myra is struck that her mother never includes Joan in these talks about her siblings. It’s as if Joan is not quite a person, or worse yet, as if she’s something unnameable and heavy that must be transported from room to room in order for the Larkins to survive, like some huge bag of sand that, if not continuously moved, will eventually fall through the weakening floorboards and take everything with it.

Back in her bedroom Myra finds a strip of her seventh-grade class photos. She scissors one of them away, sure to trim the edges just so. She thinks she looks naive, like a little girl, slightly stunned by the flashbulb, as if the photographer had sneaked up on her. But her smile is okay—nice, even—and it’s the only recent photo she has. She writes a short note, folds it in half, slips the photograph into the crease, and seals it in an envelope, which she addresses to Mickey Mantle, care of Yankee Stadium, the Bronx, New York, NY, 10451, just as he instructed. She licks a stamp and affixes it to the upper-right corner. She’ll mail it first thing tomorrow, following her morning chores.

After that she opens her diary and tapes the silver dollar onto a new page. Under it she writes the following letter:

Sunday, August 19th, 1951

Dear Holden,

Today I met a boy at the diner. He was very handsome and polite. His name is Mickey and he’s a professional baseball player who is an outfielder for the New York Yankees and he also fought in the Korean conflict. He has blond hair and blue eyes. He gave me a silver dollar, which I’ve taped to the page above. He also gave me a picture of himself from when he was in the army. He is so young to have accomplished so much. I think if you met him you’d like him. You might even be friends. I know how you prefer polite people to those who are cruel or rude, like your annoying dormitory neighbor, Robert Ackley. Mickey is very polite. He even gave me a ride home in the rain. He has a very nice yellow car.

Other noteworthy news is that my baby brother, Archie, is sick with a fever. My mother was angry with me because I was late coming home, so I won’t be able to go to the diner next week. I will miss you.

I’m sure Archie will be fine. Babies get sick all the time.

In closing I want to write that I consider this to be a special day and I’m glad that I could share it with you.

Yours Sincerely,

Myra Lee Larkin

DURING DINNER, VERY LITTLE is said. Everyone is concerned about Archie, whose fever hasn’t broken. Ava has placed him in his bassinet, which is parked beside her, at the foot of the table. There are cucumber slices arranged on his naked torso. When Lexy asks her mother why there are cucumbers on him, Ava tells her that they help to draw the fever out.

Fiona picks at her meat loaf and Joan seems to be arranging her peas as if to protect them from the rest of the food on her plate. At the head of the table, her father eats with a slow intensity, his eyes cast down. Myra waits for any cue from her mother that will signal she needs help. The smallest look can send her into the kitchen for more salt or napkins, or a clean fork. Alec still hasn’t come home from who knows what—his only friend Roland’s house? throwing rocks off a bridge?—and no one seems interested in mentioning it.

A portrait of Jesus hangs on the wall above the dining room table. It’s been in that spot for as long as Myra can remember. Jesus’s golden hair is wavy, his brown eyes deep and kind and round. Sometimes Alec will tilt the frame so it looks crooked. Ava will correct it without comment or, apparently, suspicion. Tonight Jesus looks different. His face, usually imbued with benevolence, seems beset by mischief, as if he’s harboring a naughty joke he’s just overheard.

Archie makes very little sound, only a chirp here and there. Ava keeps dipping her napkin in her water glass and dabbing at his forehead. She quietly sings to him:

Give me oil in my lamp, keep me burning

Give me oil in my lamp, I pray

Give me oil in my lamp, keep me burning

Keep me burning till the break of day

Myra’s mother has a beautiful voice. She sings in the choir at church and often gets a solo during the Christmas recital. Joan stops eating and stares at her, entranced. Lexy joins in with the singing, not quite forming some of the words, and warbling other shapeless vowels, as if under a spell.

Sing hosanna! Sing hosanna!

Sing hosanna to the King of Kings!

Sing hosanna! Sing hosanna!

Sing hosanna to the King…

AFTER DINNER MYRA GOES into her father’s study, where Donald sits in his plaid recliner, smoking a pipe and reading the Star-Gazette. Beside him, his old Philco Cathedral radio reports the news.

More than a hundred people are dead from a hurricane in Jamaica…

Reds threaten the U.N. with annihilation…

Major battles erupt on the Korean front…

Myra’s father is a machinist at the tool-and-die in nearby Horseheads. He’s a year younger than Myra’s mother and speaks so infrequently that many Elmirans believe the war—specifically his difficult time in the Hürtgen Forest—took his voice away. He’s more apt to talk at home, especially after dinner, when he sits by the radio with his pipe and newspaper. Myra can sometimes coax entire sentences out of him—quiet, careful half sentences, really—but she looks forward to these few minutes with her father, who, except for Sunday Mass, rarely changes out of his drab gabardine work clothes. He can be seen in the Larkins’ driveway nearly every Saturday morning, polishing the Chrysler’s engine with vinegar.

“Come sit,” he tells Myra, who perches on an old dining room chair that squeaks, the only other one in the room.

Donald’s study is a glorified alcove, really, with a window and the two

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...