Writ upon these hallowed pages is the epic tale of the great wizard Jude. His power was rivaled only by his immeasurable charm. His life was a series of grand adventures—battles won and battles lost, evil vanquished and goodness restored. He was a true hero of legend. His story, as penned on this brittle parchment, is a worthy one—a quest for the ages. A destiny built on fortune and misfortune, blessings and curses … and a love that has inspired the music of bards across the centuries.

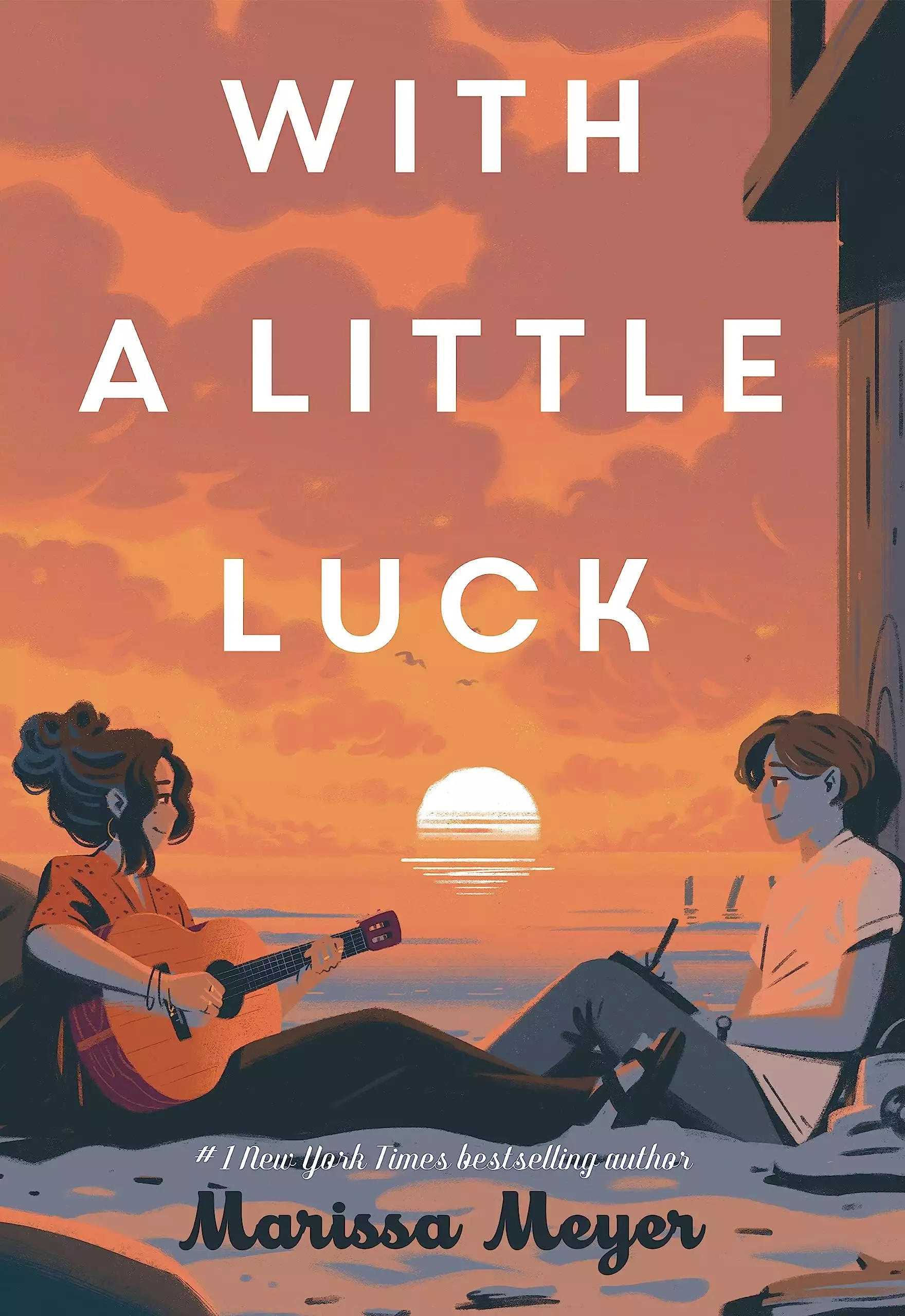

Or, depending on your interpretation, it could also be the story of a sixteen-year-old boy, halfway through his junior year at Fortuna Beach High School, who works four days a week at his parents’ vinyl records store. The sort of boy who draws comics when he’s supposed to be taking notes on the Industrial Revolution. The sort of boy who isn’t sure he’ll ever be able to afford college … or a car, for that matter. The sort of boy who would rather take a lightsaber to his non-drawing hand than risk the rejection that comes with asking out a girl he likes and, thus, has never asked out a girl, no matter how many times he’s imagined how it might go if he did. The possible good … and the far more likely, almost inevitable, bad.

But it’s fine. I’ve got a decent imagination, which is almost as good as epic quests and true love. Imagination surpasses real life … what? Ninety percent of the time? Tell me I’m wrong. You’re the one with your nose in a book right now, so I know you agree with me, on some level.

“The Temple of Torna Gorthit?” says Ari, startling me from my targeted destruction of the fourth wall. (Theater joke—don’t worry about it.) She’s reading tonight’s open mic night flyer over my shoulder, the flyer I’ve been doodling on for the past ten minutes. “Sounds ominous, Jude.”

“It is rife with danger,” I say. The ballpoint pen scratches across the white paper, transforming the clip art of a vinyl record into a black sun hanging over a tree-studded horizon. I’ve altered the letters in OPEN MIC to look like an ancient temple, crumbling from time. “I’m still working on the name. Naming things is hard.”

Ari leans closer. She has her hair pulled back in a loose, messy bun, but one strand falls out, brushing across my forearm before she reaches up to tuck it behind her ear. “Is that supposed to be me?”

I pause and study the flyer. Ventures Vinyl presents … Open Mic Night! 6 p.m., the first Sunday of every month. All musical styles welcome. The bottom half of the page used to be taken up with a line art sketch of a girl playing a guitar, but I’ve changed the guitar to look more like a medieval lute, lengthened the girl’s hair, and given her a cloak and riding boots. Very medieval chic.

“Um, no,” I say, tapping the drawing. “This is Araceli the Magnificent—most renowned bard in all the land. Obviously.”

Ari widens her eyes knowingly and whispers, “I’m pretty sure that’s me.”

I lift up the page and turn it to face her. “This is a lute, Ari. Do you play a lute? Do you?”

“No,” she says, studying the drawing before adding, “But I bet I could.”

“Yeah. Araceli the Magnificent likes to show off, too.”

Ari laughs. “So what happens in this creepy temple?”

“A group of bards compete in a music competition. To the death.”

“Yikes.” She hops up onto the counter. She’s short, but somehow she makes it look easy. “Do lots of bards sign up for that?”

“It’s either compete in the tournament or have your video go viral on YouTube and be subjected to the comments of a hundred thousand trolls. Literal trolls. The smelly kind.”

“I see,” says Ari, legs swinging. “Death sounds preferable.”

“I thought so, too.” I pick up my pen again, adding vines and foliage around the base of the temple. “I’m actually still figuring out the magic of this temple. I know there’s going to be a statue in the last chamber, and I’ve got this idea that maybe there was a maiden who was cursed and turned to stone, and only someone deemed worthy can break the spell. If they succeed, they’ll get bonus points on future skill checks. Like—magic that gives you uncanny good luck. But if they fail … I’m not sure yet. Something bad happens.”

“Humiliation

smelly internet trolls?”

I nod earnestly. “It’s a slow, painful death.”

The record player clicks off. I’d forgotten it was playing, but I start at the sudden absence of music.

“You’re a really good artist, Jude.” Ari reaches for the beat-up guitar case leaning against the counter. “Thought any more about art school?”

I scoff. “I’m not lucky enough to get into art school.”

“Oh, please,” she says, unclipping the latches on the side of the case. “You have to at least try.”

I don’t respond. We’ve had this discussion half a dozen times over the last year, and I have nothing new to add to it. The people who get into art school on full-ride scholarships are incredible. Like, the sort of people that BeDazzle their own bodies with Swarovski crystals, call them blood diamonds, and host a faux human auction in the middle of Times Square in order to make a point about immoral mining practices. They are artistes—French pronunciation.

Whereas I mostly draw dragons and ogres and elves in kickass battle armor.

Ari pulls out the acoustic guitar and settles it on her lap. Like most of the clothes Ari wears, the guitar is vintage, inherited from a grandfather who passed away when Ari was little. I’m no expert, but even I can see that it’s a beautiful instrument, with a pattern of dark wood inlays around the edges of the body and a neck that looks black until the light hits it in just the right way to give it a reddish sheen. The glossy finish has been rubbed away in places from so many years of play, and there are a few dings in the wood here and there, but Ari always says that its historic patina is her favorite thing about it.

While she tunes the strings, I lift the lid on the turntable and slide the record back into its protective sleeve. The store has been slow all day, with just a few regulars stopping in and one tourist family, who didn’t buy anything. But Dad insists that we always have music playing, because we are a record store. I’m reaching for the next record on the stack—some ’70s funk band—when Dad emerges from the back room.

“Whoa, whoa, not that one,” he says, snatching the record from my hand. “I’ve got something special picked out for our inaugural open mic night.”

I step back and let Dad take over, especially since choosing our music selection on any given day is one of his greatest joys.

It’s not actually our inaugural open mic night. Ari had the idea last summer, and with Dad’s okay, she officially started hosting them sometime around Thanksgiving. But this is the first open mic night since my parents finished signing the paperwork to officially buy Ventures Vinyl. The business itself was always theirs, but as of six days ago, they are now also the proud owners of the building, too. A twelve-hundred-square-foot brick structure in the heart of Fortuna Beach, with old plumbing, old wiring, old everything, and an exorbitantly high mortgage payment.

Proof that dreams do come true.

“Should be a good crowd tonight,” Dad says. He says this every time, and while we’ve progressively become more popular over the months, it’s considered a “good crowd” if we top more than twenty people.

It’s been pretty fun, though, and Ari loves it. She and I both started working here last summer, but we were friends for years before that, and she used to spend so much of her free time here that Dad often refers to her as his sixth child. I think she would work here even if he wasn’t paying her, especially on open mic nights.

Ari tells people these shindigs are a team effort, but no. It’s all her. Her passion, her planning, her effort. I just drew some flyers and helped assemble the platform in the corner of the store. I guess it was my idea to frame our makeshift stage with floor-to-ceiling curtains and paint a mural on the wall behind it to look like a night sky. Dad says it’s the best-looking part of the store, and he might be right. It certainly has the freshest coat of paint.

“Here we go,” says Dad, flipping through the bin of records beneath the counter. The special or sentimental ones that he keeps for the store but aren’t really for sale. He pulls out a record with a black-and-white image of two men and a woman standing in front of the London Bridge. It takes me a second to recognize Paul McCartney from his post-Beatles days. “All we need is love,” Dad goes on, pulling out the album and flipping it to side B before setting it tenderly on the turntable, “and a little luck.”

“Don’t let Mom hear you say that,” I say quietly. Dad has always been the superstitious one, and Mom loves to tease him about it. We’ve all heard it from her a million times, and I parrot now: “Luck is all about perspective…”

“And what you do with the opportunities you’re given,” Dad says. “Yes, yes, fine. But you know what? Even your mom believes in luck when Sir Paul is singing about it.”

He lowers the needle. The record pops a few times before some deep, mechanical-sounding notes start to play over the store speakers.

I cringe. “Really, Dad?”

“Watch it,” he says, jutting a finger in my direction. “We love Wings in this family. Don’t criticize.”

“You don’t like Wings?” Ari says, shooting me a surprised look as her feet kick against the side of the counter.

“I don’t like…” I consider for a moment. In my family, we’re pretty much required to have a healthy respect for the Beatles, and that includes the Fab Four’s solo careers. I think my parents might actually disown me or my sisters if we were to ever say something outright critical of John, Paul, George, or Ringo. “I don’t like synthesizers,” I finally say. “But to each their own.”

“I’m going to start setting up the chairs,” says Dad. “Let me know if you need help with anything else.” He wanders toward the front of the store, humming along with the music.

I glance at Ari. She has one ear tilted toward the closest speaker as she plays along to the song. I can’t tell if this is a song she already knows, or if she’s figuring out the chords by ear. It wouldn’t surprise me if it’s the latter. Pretty much all I remember from my brief stint taking guitar lessons years ago is how to make an A major chord, and how much my fingers used to hurt after pressing on those brutal strings for an hour. But Ari speaks the language of notes and chords as fluently as the

Spanish she speaks with her family at home.

“So,” I say, folding my arms on the counter, “are you going to start the night off with an Ari original?”

“Not tonight,” she says dreamily. “There’s a really beautiful cover song I want to do first.”

“But you will play at least one of your songs, right? That’s kind of the point of open mic night. To play original stuff while your captive audience can’t escape.”

“That’s rather a pessimistic view. Here I thought the point was to support artists in our community.”

“That’s what I said.” My grin widens. “I like it when you do originals. I stan you, Ari. You know that.”

She starts to smile, but then diverts her attention back down to her guitar strings. “You don’t even like music that much.”

“Hey, only psychopaths and Pru don’t like music. You can’t put me in that group.”

Ari gives me a side-eye, but it’s true. I like music as much as the next guy. My appreciation just pales in comparison to the absolute obsession my parents have—and Ari, too, for that matter. My fourteen-year-old sister, Lucy, has pretty eclectic tastes and has been to more concerts than I have. My ten-year-old sister, Penny, practices her violin for forty-five minutes every night without fail. And my littlest sister, Eleanor—a.k.a. Ellie—sings a mean rendition of “Baby Shark.”

Only Prudence, my twin sister, missed the music gene. She does like the Beatles, though. Like, really, really likes the Beatles. Though again, this could just be her attempt to not get disowned. See Exhibit A, above.

“Okay,” says Ari, “then tell me your favorite song of all time.”

“‘Hey Jude,’” I say, no hesitation. “Obviously. It’s, like, the song that made me famous.”

She shakes her head. “I’m serious. What’s your favorite song?”

I tap my fingers against the countertop glass, under which is sandwiched an assortment of collected memorabilia. Ticket stubs. Guitar picks. The first dollar this store ever made.

“‘Sea Glass,’” I say finally.

Ari blinks. “My ‘Sea Glass’?”

“I’m telling you. I am your biggest fan. Pru likes to claim that she’s your biggest fan, but we both know she would pick a Beatles song as her favorite.”

For a second I swear I just made Ari blush, which is not something I can say about many girls. I almost laugh, but I hold it back, because I don’t want her to think I’m making fun of her. But then, since I don’t laugh, the moment starts to feel awkward.

Over the speakers, Sir Paul is singing about how everything is going to work out, with just a little luck.

Ari clears her throat and tucks that same strand of hair behind her ear again. “I’ve been working on something new lately. I thought of playing it tonight, but … I don’t think it’s ready.”

“Oh, come on. It’d be like … workshopping it.”

“No. I don’t know. Not tonight.”

“Fine. Keep your groupies in suspense. But I’m just saying”—I hold up the doodled flyer again—“Araceli the Magnificent would never pass up an opportunity to mesmerize

a crowd with her newest masterpiece.”

“Araceli the Magnificent plays to taverns full of drunken hobbits.”

“Halflings,” I correct.

Ari smirks and jumps down off the counter. “How about this?” she says, setting her guitar back into its case. “I will play my new song if you submit one of your drawings for publication somewhere.”

“What? Who would want to publish one of my drawings?”

“Uh—lots of places? How about that fan magazine you like?”

I try to remember if I ever told her my deeply buried dream of having an illustration printed in the Dungeon, a fanzine that covers everything from the Avengers to Zelda.

“Just submit something,” she says, before I’ve had a chance to respond. “What’s the worst that could happen?”

“They reject me,” I say.

“You don’t die from rejection.”

“You don’t know that.”

She sighs. “It doesn’t hurt to try.”

“It might, actually,” I counter. “It might hurt very much to try.”

Her frown is disapproving—but I can deal with Ari’s disapproval. Or Prudence’s. Or my parents’. It’s the possible disapproval of the world at large that grips me in agonized terror.

“Rejection is part of the life of an artist,” she says, tracing a sticker of a daisy on her guitar case. “The only way to know what you’re capable of is to put yourself out there, and keep putting yourself out there, again and again, and refusing to give up—”

“Oh god. Stop. Please. Fine, I’ll consider submitting something. Just—no more pep talks. You know they stress me out.”

Ari claps her hands together. “Then my work here is done.”

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved