- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

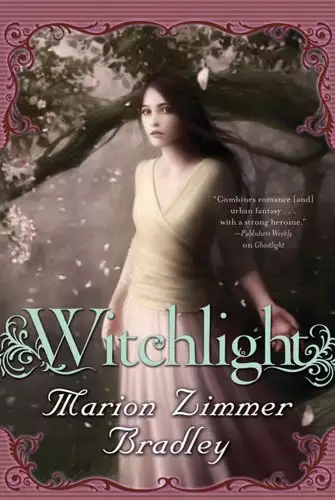

Marion Zimmer Bradley, one of the most beloved and praised fantasy storytellers of our time, has once again written a compelling and powerful novel with larger-than-life characters.

Winter Musgrave's past is largely blank, her memories missing or tissue-thin. She seem to be possessed--objects shatter when she passes, the corpses of animal appear on her doorstep. And she has the terrible feeling that something horrible happened in her empty past--results of which are now haunting her with unbridled fury.

Seeking help, Winter turns to Truth Jourdemayne and learns that the key to unlocking her lost memories lies within herself--and in the magickal circle of friends in college. But the circle was broken long ago. Winter must reconstruct it is she is to save her life.

Not just the story of a woman's search for her missing past, Witchlight is a powerful novel of contemporary fantasy that pulls readers in and hold them until the final page. Anyone who loves good contemporary fiction will devour Witchlight.

At the Publisher's request, this title is being sold without Digital Rights Management Software (DRM) applied.

Release date: December 8, 2009

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Witchlight

Marion Zimmer Bradley

1

A Winter's Tale

A sad tale's best for winter. I have one of sprites and goblins.

--WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

THE HOUSE was called Greyangels. It had been built in the last years of the old colony and added to in the first years of the new nation. Old orchards from its days as a farm still surrounded the house; their hundred-year-old trees long past fruiting but still able to bring forth a glory of apple blossoms each spring. But the house's days of ruling over acres of corn and squash and rows of neatly barbered apple trees were long past. Now, only the house remained. Its pegged, wide-planked floors, its lath-and-horsehair plastered walls, its low ceilings with their smoke-blackened beams, its tiny windows with their wavery, hand-rolled glass, had dwindled from luxurious to old-fangled to quaint to dowdy, before being forgotten entirely and abandoned to the mercy of time and the seasons.

Years passed. The house was nearly dead when it came to the attention of the living once more, to be gently renovated to suit the tastes of a generation raised with indoor plumbing and furnace heat, a generation which summered outside the city. But tastes and fashions continued to change, and soon New Yorkers had less desire for an old summer house on the banks of the Hudson River.

The house passed from hand to hand to hand, drifting farther even from the memory of its initial purpose, as cars got faster and roads improved and the suburbs moved north and north again, until Dutchess County was filled with New York commuters racing for their daily trains and it seemed that Amsterdam County, too, would soon fall to tract housing and the desire of the city's residents to reside in the peace of what once had been country.

But for now the house was spared, sitting on its dozen acres between the railroad and the Hudson, its nearest neighbor a private college with a lurid reputation and an artists' colony that sought anonymity above all things. For a while longer the old farmhouse still sat quietly in the quiet countryside, and nothing disturbed its peace.

THAT MUST BE why I came here, Winter Musgrave told herself, although to be brutally accurate, she could not remember the precise details of her flight here, and prudence--or fear--kept her from reaching too forcefully into the ugly confusion where the memory might lie. There were things it was better not to be sure of--including the frightening knowledge that her memory had--sometime in the unrecorded past--ceased to be her willing servant and had become instead a sadistic jailer waiting to spring new and more horrible surprises on her. A day that did not bring some jarring revelation, however small, was a day Winter had learned to treasure.

The quiet helped, and the slow pace of the countryside as it ripened into spring. She had a vague understanding that she had not been here long; old snow had still lingered in shadows and hollows when she had driven her white BMW up the curving graveled driveway, and now only the palest green of half-started leaves softened the outline of the surrounding trees: birch, maple, dogwood--and the apple trees in gnarled files marching down to the river.

Winter did not like the apple trees. They worried her and made her feel vaguely ashamed, as if something had been done among the apple trees that must never be remembered, never spoken of. The orchard formed an effective barrier between Winter and the river that could be glimpsed only from the second-floor bedroom.

But she could see the apple trees from there, too, and so Winterhad made her bedroom downstairs, in the tiny parlor-turned-spare-bedroom off the kitchen, which was both warmer and hidden from the sight of the flowering orchard.

So long as no one knew where she was, she was safe.

The notion was a familiar one by now; familiar enough that it might even be safe to think about.

Why should no one know where I am?

Winter picked up a heavy carnival-glass paperweight from the Shaker table and stared down at its oil-slick surface as if it were a witch's crystal and she could find answers there. Wordless reluctance and fear surged over her, making her hastily return the paperweight to the table and nervously pace the room.

The front parlor of the farmhouse was sparsely furnished; there was the Shaker table with a lamp on it, a Windsor rocker made of steam-bent ash, and a long settle angled before the fieldstone hearth. A hand-braided rag rug softened the time-worn oak-planked floor, and on one whitewashed wall hung a mirror, its thick glass green with age, set in a curving cherry frame.

Winter stopped automatically in front of the mirror and forced herself to look. It could not hurt more than coming upon her reflection by surprise, when the clash between what she saw and what she remembered fashioned another of the small humiliations and terrors by which she marked out her days.

Hair: not wavy and chestnut any longer, but flat and lank and dark. The skin too pale, its texture somehow fragile, flesh drawn tight over prominent bones that said the border between slender and gaunt had been crossed long ago. Hazel eyes, sunken and shadowed and dull; a contrast to the days when more than one admirer had sworn he could see flecks of baltic amber in their sherry-colored depths. Her mouth, pinched and pale and old. She couldn't remember the last time she'd worn lipstick, or what color it had been. Did she even have a lipstick here? She couldn't remember--did it matter?

Of course it does--Jack always said I should wear as much warpaint as I wanted; it made them nervous ... .

The scrap of the past flashed to the surface like a bright fish and was gone; pushed away; sacrificed to the need to hide.

From what? Frustration almost made Winter willing to risk thepain of trying to remember. Restlessly, she made the circuit of her world again: the front parlor, with its welcoming hearth; the kitchen, looking out on the remains of someone's garden and a windbreak of tall pines; the downstairs bedroom, bright and homelike with patchwork quilts on the white iron bed and a bright copper kettle atop the pot-bellied woodstove; the entryway with its door to the outside world and the staircase leading to the second floor--the place that held so many frightening possibilities. From the front hall she could see the woodshed that held half a rick of oak and pine split for burning, and that held her car as well. She'd need to bring in more wood soon, for the electric heat that provided the farmhouse's heat was feeble and unreliable, and she'd learned to keep fires burning both in the bedroom stove and the fireplace in the parlor to fend off the chill of early spring.

But that would mean she'd have to leave the house; to walk outside in the open air.

How long has it been since I've gone outside? Sheer stubbornness made her demand an answer of her memory, and at last the image surfaced: Winter, carrying suitcases--suitcases?

--slipping on patches of rotting ice in her haste to get into the house, running away from ...

The knowledge was so close she could nearly grasp it; she shied away, knowing that the balance between fear of knowing and fear of ignorance would soon shift, and she would reclaim at least that fragment of her past. Even though it must be something terrible, to drive her to hide here, crouching behind closed shutters and drawn curtains like a wounded animal in its burrow.

I haven't been out of this house in ... weeks, her thought finished lamely. It was no good knowing that this was April--surely it was April; the new leaves and the masses of daffodils she could see from the window told her it must be April at least--if she did not know when she'd gotten here. March? Was there still snow on the ground in March? Maybe it had been February ...

But whenever it had been, she had spent enough time since then indoors. More than enough. Spring was the season of rebirth; it was time for her to be born.

There was a sudden copper taste in her mouth, but this time the fear seemed to spur her determination rather than hinder it. Before she could think what she was doing, Winter strode into the hall and flung open the door to the outside.

The living air of the countryside spilled in, and the sunlight and the breeze on her skin were like messengers from another world. The spaded earth alongside the flagstone path was dark and fragrant with recent rain, and tiny sharp grass blades lanced up through the soil beside the darker, more established green of daffodil and iris, tulip and lily of the valley. The flagstones curved down and to the left, to meet the graveled drive that led from the garage to the outside world.

There was no one anywhere in sight. Not even the road was visible, and no traffic noise disturbed the illusion that time had not gone forward since the farmhouse had first been built.

It's okay. It really is. There's nothing out here that can hurt me, Winter told herself bracingly. With as much determination as courage, she stepped from the house to the flagstoned path.

One step, two ... As she left the shadow of the house a wave of giddy disorientation broke over her; she felt the same faint lightheadedness that she imagined one would feel opening a tiger's cage. The rolling pastoral landscape around her seemed to rear up like an angry bear, threatening to crash down upon her and rend her to bits.

It's just your imagination! That's what they always said ... . A sudden flash of memory swirled out of the vortex of sensation, striking sharklike without warning.

Another vista of green, but this time tamed and tended. Bright autumn sunlight warming the terrace, where patients in discordantly cheery bathrobes stared mutinously out at the sanatorium's landscaped grounds.

The sanatorium--yes! I remember Fall River. Did I escape from ...

But no. The memory was clear of the weeks of desperate courage: first to refuse her medication, then, to leave. She was an adult, she had checked in of her own free will; they really had no reason to hold her.

And at thirty-six one ought to know one's own mind! Winter thought with a flash of gallows humor. So she had left--why hadshe left?--had they said she was cured?--surely she ought to feel better than this if she had been pronounced sane and well?

They were talking about me ... . Another hard-won memory, and now her tottering steps brought her to the shelter of an ancient oak, and the refuge of the bench that some former tenant had built to encircle its trunk. Winter sank down on the moss-green wood and looked back toward the house.

Talking about her at the sanatorium. Saying it was just her imagination, when she knew it was not, that the tales they ascribed to the inventive fancies of a disturbed and unbalanced mind were real.

I did not make it up.

Grimly she clung to that truth, but the act took all Winter's strength, and she had none to spare for the effort of remaining outside her refuge. She forced herself to walk slowly, not to surrender to blind panic, but her mouth was dry and her chest was crushed by iron bands by the time she could shut the front door of the farmhouse behind her once again.

The staircase beckoned; the elusive second floor of the house. That, and the memory of the suitcases, and the need to draw some triumph from the jaws of this latest defeat made Winter put her hand on the newel post and her foot on the first of the risers.

This isn't so hard! she told herself rallyingly a few moments later, even risking a quick peek out the window on the landing. She could see the roof of the woodshed from here, its slates knapped and mellowed with age.

Only three more steps.

The second floor was smaller than the first. It held two bedrooms and a modernized bath, its pink and white fifties curves Rubenesquely out of tune with the house's Shaker simplicity. The largest bedroom was the back one, and Winter, peering through the door, saw two Vuitton suitcases and a Coach Lexington brief in British Tan flung haphazardly onto the bed.

She could go downstairs now. She could leave that reclamation of her identity for another day, along with that sense that to reclaim herself meant also to take up some awful burden.

But if I don't, there's no one else to do it.

She could not say where that certainty outside of time had comefrom--it would be so easy to dismiss this sense of special purpose as just one more of the daydreams of the delusional. When she had tried to talk about it at Fall River she'd been hushed and dismissed, until she'd prayed for the nagging sense of mission to go away, to leave her normal; to make her seem to respond to their treatment and their drugs just like all the others who came to ...

To that privileged retreat for failed overachievers, Winter finished with a flash of mockery. But the words weren't hers. Whose?

Never mind that now. Her mind was trying to distract her with inessentials to keep her from acting, but she knew that trick by now. Squaring her shoulders, Winter stepped over the threshold into the bedroom.

THESE WERE the bags she--or someone--had packed when she went to Fall River. She emptied the contents of both Vuitton cases onto the sere candlewick bedspread; all casual clothes, resort clothes; but somehow, by accident, her pit pass from Arkham Miskatonic King was there. She stared at the photo.

I look like I've been caught in the headlights of an oncoming train ... . Despite which, it had been her proudest possession since the day she'd qualified for the Pit. As a commodities broker. On Wall Street.

As smoothly as that, the missing past rushed in. She was Winter Musgrave, a trader at Arkham Miskatonic King on Wall Street. She'd been there for ten years, since they'd romanced her away from Bear Stearns ...

She remembered getting up early in the morning to walk to work when the subway was on strike; remembered her apartment. If she opened the briefbag lying on the bed now she could say just what it would contain: the Wall Street Journal and a bag full of throat lozenges; a pink stuffed elephant--a good-luck charm--and a spare T-shirt to change into; extra pens ...

My life, in short.

She'd had no life, outside of the Street. And she hadn't wanted one, either. She'd ignored all well-meaning advice to ease up, slow down, find a hobby, get a life.

I had a life.

Until that break between past and present; the event that she could not yet remember. That she now knew would come in time, and explain, perhaps, this purposeless sense of purpose.

Shaking her head, Winter gathered up an armful of clothes. If she was going to stay downstairs, she might as well have her clothes with her. At least she could pretend she was normal.

But don't crazy people always think they're normal? Isn't that how it starts?

No. It had started with the breakdown that had brought her to Fall River--and now she was out of Fall River, but not because she was better ... .

Face it--FACE IT!

Winter ran down the stairs; not running away, but running to the only thing left to frighten her; the thing that had driven her into this long fugue state.

The clothes she had gathered scattered behind her like autumn leaves. She flung herself across the serene parlor and into the cheerful kitchen. Here were the dutch doors leading out into the garden; to the orchard; to the river. She threw open the door and recoiled with a cry, even though she had seen what was there before; had seen it this morning, in fact ... .

The creature was difficult to identify, although from the size, it had probably once been a squirrel. Only a few wisps of gray fur clung now to the ruined blob of shredded meat flecked with white spurs of shattered bone.

Like all the others. Just like all the others.

It began with pigeons. Pigeons and squirrels and mice; she'd found the tiny bloodless corpses everywhere she went until each new discovery had been almost beyond bearing. When she'd gone to Fall River there had been no more for a while, but then the bodies had begun appearing again, and when she'd sworn she had nothing to do with the deaths, Dr. Atheling said he believed her but none of the others did. They said she was doing it herself--that she was the one responsible: catching and hurting and killing ... .

And so she had run away, praying that if she ran far enough,hard enough, she could outrun that vengeful shadow. And for a while she'd thought she'd succeeded.

Until today.

WINTER WAS RESTLESS all the rest of the day, as if the appearance of the tiny shattered body had brought with it a summons that could no longer be denied. Winter spent that night sleepless before the old fieldstone fireplace, feeding the last of the woodpile to the greedy flames.

With the morning light came the certainty that she could hide here no longer. If she was sane, she could test that sanity in the outside world. If it failed, she'd ...

What?

I can't go back there, Winter told herself, although Fall River Sanatorium was not a bad place--not like some she'd heard of, where malice was disguised as concern and sadism took the place of care.

It's just that Fall River is a place that should help people--and it can't help me.

Even without knowing where the conviction came from, Winter trusted it--even though she no longer trusted herself.

I guess the world--and I--will just have to take our chances.

THE MORNING was spent in a thousand delaying chores. Even though each strengthened her confidence in her ability to function outside the safe refuge the farmhouse had become, they were also a form of escape from the consequences of her decision. She washed the dishes, and made a list of the things she would need to replenish her larder in town, carried the rest of her clothes downstairs and put them away in the large red cedar armoire that shared the kitchen parlor with the woodstove and the white iron bed, and even went through her purse and Coach briefbag, alternately amazed and baffled by the contents. There were a fistful of unopened monthly statements, forwarded to her at Fall River from the accountant who paidher monthly bills. Winter glanced at one of them, but the rows of numbers, of transfers and debits, were a meaningless jumble.

More real were the wads of twenties and fifties crammed at the bottom of the bag--enough to take care of any conceivable immediate expense--crumpled loose in the bottom of the purse like so much play money.

Play money. That's what it was to us. We were like kids with a Monopoly set--none of it was real to us, she thought, clutching the small pink stuffed elephant that had been at the bottom of her Lexington brief, along with a Wall Street Journal with last year's date and clutter of things almost unfamiliar to her now. Her years at Arkham Miskatonic King were solid but curiously distant, as if out of a particularly vivid book she'd read and enjoyed. She'd lived fast and high, bought the usual toys and paid for the usual perks, and none of it was unique to her, somehow. It was the sort of life that any of the traders could have had, as unindividuated as the life of a drone in a hive.

And we thought we were so special, and all along we were just a funny kind of moneymaking robot. Wind us up and we'd trade, and trade, and trade, until ...

But Winter still wasn't sure what had taken her from the floor of the New York Stock Exchange, to Fall River, to here. Maybe she'd just gotten ... tired? People did, after all. Burnout was the commonest reason for leaving the Street.

But not Winter's reason. Even if she didn't know what her reason was, she knew that much.

At last she could delay no longer without acknowledging to herself that she was running away from the outside world. She changed her scruffy jeans and worn-out sweater for something more suitable to an appearance in town. Although Glastonbury isn't much of a town, as far as I can remember.

THE FASHIONABLE, expensive woman in the gray cashmere sweater and Harris tweed skirt who stared back at Winter from her bathroom mirror was gaunt and hollow-eyed until Winter painted the illusion of health into her skin with cosmetics labeled Chanel andDior. Expensive accessories for a lifestyle she had once worshiped with all her heart, that now more and more seemed a silly and expensive sort of mistake. But the rouge, and the Paloma Picasso earrings, and the thin sparkle of Elsa Peretti "Diamonds By The Yard" all helped disguise the sleepless nights filled with fear.

THIS TIME Winter made it all the way to the woodshed, although the open space around her seemed vast and threatening and she felt as if the sky would fall and crush her. She ducked into the shed with a tiny cry of triumph, and rested her forehead for a moment against the BMW's white lacquered roof.

Maybe Chicken Little was right. It's a possibility. Her heart was beating far too fast, and for a moment Winter considered turning back--she'd done enough for one day; no one could ask her to do more ... .

Except me. I can ask me to do more ... .

And she was running out of time.

Winter wasn't certain where that conviction came from, but it was enough to galvanize her into unlocking the car and settling inside. When she put the key into the ignition, she had one wild pang of panic--suppose it didn't start? suppose something terrible happened?--but fought past it. She had to know if she could survive out here in the real world. If she could not manage as simple a task as going into town for supplies, then she had better call Fall River and tell them where to find her.

And learn to live surrounded by the baffling and terrifying deaths.

Winter turned left out of the driveway almost at random--If Glastonbury wasn't this way then she'd retrace her tracks--and drove to the bottom of a hill, where one sign identified the crossroad as Amsterdam County 4 and another said Glastonbury: 6.

As she followed the winding two-lane road, Winter got intermittent glimpses of the river, and more information floated to the surface of her battered memory. The grandiosely named little town of Glastonbury, New York, dated from the nineteenth century, and served the local college as well as Amsterdam County locals such as herself. There was a supermarket, a post office, even a smallmovie theater, though most people preferred to drive to the multiplexes in the malls south of here.

It was the sort of thing that anyone might know, particularly anyone who had rented a farmhouse and come to stay for an extended period, and the ability to remember such trivia was obscurely comforting. She was dressed, she was driving a car; if she really were ... sick ... she wouldn't be able to do these things, would she?

When Winter reached the town, she found it had a haunting familiarity, as if she'd been here before, but the memory was elusive. County 4 had turned into Main Street, and as Winter drove down it, she saw bright posters in the windows of the business: FREE WILL--AN EVENING OF SHAKESPEARE SCENES AND SONGS BY THE TAGHKANIC DRAMA DEPARTMENT. Students from the nearby college were everywhere at this time of day, identifiable by the universal symbols of age and backpack, trendily pierced or equally trendily grungy, but carefree in a fashion Winter could somehow not associate with herself. While stopped for a light, she watched one pair wistfully as they proceeded up the street holding hands. The boy's hair fell to shoulder length and the girl's was shaved to a spiky buzz; both were dressed identically in work boots and overalls that seemed about eleven sizes too big, and they were obliviously in love. Winter watched them until they rounded the corner, and then forced herself to concentrate on the signal and the other drivers. This outing was as much to prove she could cope as it was for anything else. She could not afford to daydream.

The supermarket was right on Main Street; and she pulled into the lot and parked with a sense of relief and growing triumph. She climbed out of the car--remembering to lock it--and stood in the warm afternoon sunlight, looking down at the list of errands in her hands.

Groceries first. And then ... the butcher, the baker, the candlestick maker ... Winter thought giddily.

Her destinations were not quite that archaic, though it hardly made sense to buy grocery-store bread with an organic bakery right up the block. Half an hour later, the first part of her self-imposed assignment completed, Winter emptied her grocery cart into the BMW's trunk: crisp clean brown paper bags containing cans ofsoup, fresh fruit and fruit juice, and all the other household necessities she'd only realized she needed when she'd seen them on the supermarket shelves. She felt almost jaunty as she locked the trunk again and headed for the bakery; it was just around the next corner, the cashier had given her directions, speaking to her as if it were a perfectly normal thing to ask for such directions. As if everything were all right.

On impulse, Winter stopped at a liquor store as she passed it, debating between Bordeaux and Nouvelle Beaujolais as though such questions could really matter. She finally settled on a bottle of white Burgundy and a trendy California Zinfandel, and proceeded up the street with her purchases cradled in one arm. She found the bakery without trouble, and bought a dozen raisin scones and a round loaf of seven-grain bread that looked as though it contained enough vitamins to nourish the entire Mighty Morphin Power Rangers. Echoes of her old life--her self-sufficient life--rose up to bolster her determination as she made her purchases. She would be fine. She would make herself be fine.

As Winter came out of the bakery, the bright colors of a display across the street caught her eye, and she went to look. There were three clear-glass amphorae in iron cradles, their liquid contents dyed bright blue, red, and green: It was a drugstore, its window used to display a collection of antique patent medicines and pharmacy supplies.

Winter dawdled by the window, looking. It was truly amazing what people had been able to buy without a prescription at the turn of the century: opium and morphine and cocaine, all packaged in pretty blue and amber glass bottles, or wrapped in boxes with labels written in serious Spencerian script. Extract of cannabis. Tincture of arsenic. Asafoetida. Cyanide.

Winter raised her gaze from the quaint display of antiquated medicines to the shelves behind them filled with their modern descendants. She took a hesitant step toward the door. Was there something in here that would cure her fears and dreams--let her sleep soundly at night and return to her New York life?

No. Regretfully, Winter shook her head. Nothing she could buy here would help--if the pretty red-and-black pills that had left herdisoriented and numb for days after she'd stopped taking them had not helped, how could aspirin and Sominex?

Even Seconal and Thorazine had not stopped the killing ... .

"I DON'T KNOW how she manages to do it." The memory-voice was irritated; one of the Fall River aides talking to another in the sitting room of Winter's suite. Perhaps they hadn't known she was there, in the bedroom beyond the open door. Perhaps they simply hadn't cared.

"Found another one, eh?" The second voice was knowing; resigned.

"They're all over the place; Dr. Luty gives her enough junk to tranquilize a horse and she still sneaks out at night."

"Think so?"

"Has to be. And I know she's not dodging her meds. And we're the ones who have to clean it up, dammit, not Luty or Atheling. You'd think the bitch'd show a little consideration."

"Nah. She's having too much fun."

THE INTRUSIVE memory receded, leaving Winter shaking. Their remembered contempt--she hadn't even known their names--still made her stomach roil. She'd done nothing to merit such hatred.

Nothing she could remember, at least.

The trembling didn't stop; Winter clutched her purchases tighter and realized that she'd grossly overestimated her stamina and emotional endurance; she'd better get back to the car and get out of here while she still had the strength to drive home safely.

She looked back the way she'd come, judging the distance. Too far, but if she turned down that street just up ahead it ought to take her right back to the supermarket parking lot.

But the street ahead only ran half a block before it made an L-shaped turn onto another street, leaving Winter farther from her car than ever. She felt sick and light-headed, as though she'd been in the sun too long, but the spring sunlight wasn't strong enough to cause anyone distress. Winter stared around herself, hoping tosee a familiar landmark or at least a place to stop and rest for a minute.

She'd managed to detour into the heart of the small riverside town, away from Main Street. Here the streets were narrow and lined with picturesque and old-fashioned shops; old storefronts intermingled with brightly renovated Victorian houses converted to commercial space. Everything was brightly inviting, but all it was to Winter was a hostile labyrinth keeping her from the safe refuge of her car and her house.

She drew a deep breath, forcing calm against the rising tide of sickness and panic. Maybe the simplest thing to do would be to just ask directions. Anyone along here ought to be able to tell her how to find Main Street again.

She turned toward the nearest shop. The sign over the storefront was carved and painted wood: a golden full moon riding a skirl of swirling purple clouds spangled with stars. The words Inquire Within were carved to the left of the moon in old-fashioned letters. There was also a crescent moon and a swirl of stars painted in gold on the window itself, and behind them, on the red satin drape of the display window, a "crystal" ball on an ornate stand, a long acrylic tube filled with glitter with a shiny holographic star on one end, and a sp

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...