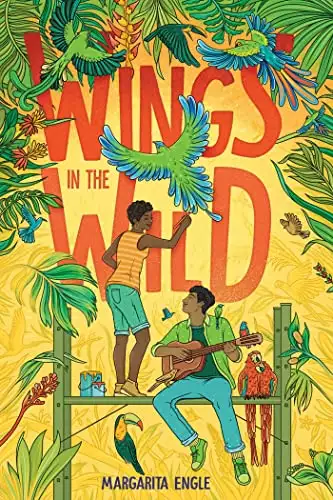

Winged beings are meant to be free,

not caged.

At the heart of our dilapidated seaside home

in the central courtyard—hidden by walls—

we have a secret museum of living statues

carved from the growing limbs

of richly hued native trees.

Deep reddish-brown mahogany like my skin,

midnight-black ebony like my eyes, and radiant

golden majagua like my sunny name.

This last tree is a wild hibiscus

with yellow flowers that attract

tiny emerald zunzunes

and their minuscule cousins

los zunzuncitos, this island’s endemic

bee hummingbirds, the smallest pajaritos

on Earth, found nowhere else, just Cuba.

¡Ay, Cuba! How we suffer here, surrounded

by imprisoned beauty.

Art Crimes

The problem with our sculpture garden

is that the statues are illegal.

Mami and Papi are dissidents—protesters

who crave

artistic liberty.

Visiting birds come and go freely

by zooming high above the coral stone walls

but we

are in a cage

imposed by Ley 349,

a decree that bans any art

that protests the banning

of art.

Carved Wingbeats

The tocororo is Cuba’s national bird.

Blue, white, and red, like our flag.

He perches and flicks his tail

back and forth

in a dance

of love.

Everyone knows that los tocororos

cannot survive in captivity.

That is why, each time I pose

as the inspiration for his sculpted form

I feel like a symbol

of liberty.

Winged, rooted, and chained,

my tocororo-self tries to fly

but always fails.

Only freedom of expression for artists

will transform these statues.

Only then will my parents cut the carved chains

that keep my winged image from soaring.