- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

This eerie tale sees a group of men haunted by one traumatic event from their childhood. They thought they'd moved on . . . but someone - or something - won't let them!

1988: Thirteen-year-old Andy Miller and his friends – Carl, Brian, Johnny and Gavin – become witnesses to the vicious attack of their classmate, Poppy, and the brutal murder of her sister at a flooded railway line they call the frog ponds. They lead the police to a suspect, a vulnerable older boy whose differences single him out. But when he commits suicide, his guilt is never proven. And the crime goes unpunished, until . . .

Now: Carl’s body is found beside the same body of water – and the lives of the four remaining friends start to unravel. Is the hag-like woman terrorizing their every waking moment really a grown-up Poppy hellbent on revenge? Or something else . . . something steeped in childhood nightmares? Something determined to reveal the truth and punish the wicked.

For those who love spooky fairy tales with a twist - this first in a new series will not disappoint!

Release date: January 7, 2025

Publisher: Severn House

Print pages: 229

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

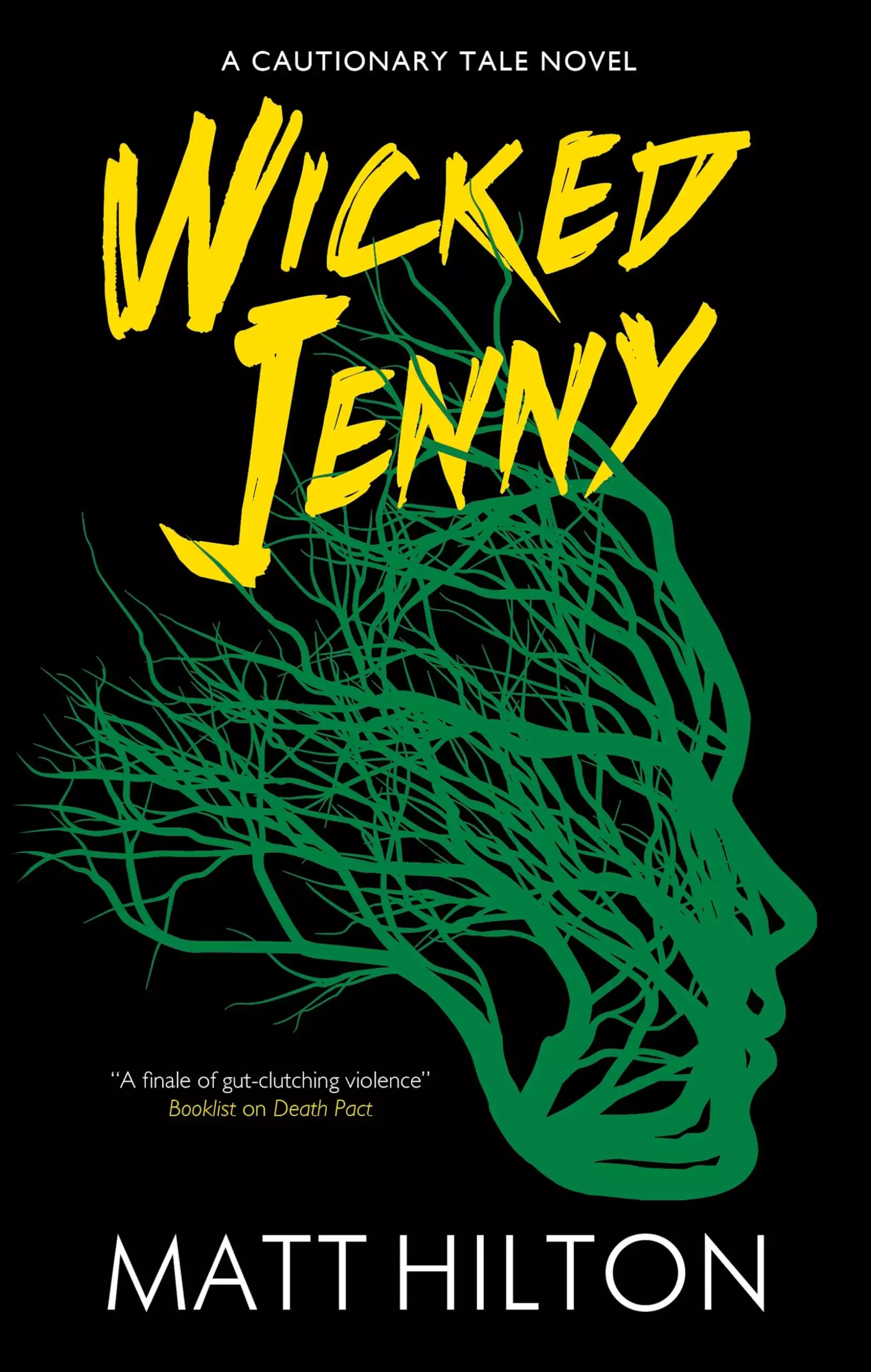

Wicked Jenny

Matt Hilton

ONE

Something felt wrong.

Carl Butler walked tentatively. In contradiction to his tiny steps, he kept his hands firmly wedged in his jacket pockets, trading balance for warmth. His chin dug deep into his collar, and he breathed deeply out of his open mouth. His gaze darted around.

The cobbles sparkled underfoot, slick from a recent downpour. The skeletal trees had practically shed their foliage, with only the most determined leaf clinging on. The fallen leaves formed decomposing mounds in the gutters and in gates and doorways. The cobblestone path had been swept, but some leaves had found their way back and made it treacherous underfoot.

He had taken this shortcut home from his local pub on dozens of occasions, sometimes even in darker and wetter conditions than these and it hadn’t bothered him. But tonight was different.

Yes, tonight felt wrong.

Wrong in an uncanny sense, at which Carl would normally sneer. He didn’t believe in ghosts, goblins or anything else that plagued the imaginations of simpletons. Yet the small hairs rising on the back of his neck, the goosebumps causing him to itch from coccyx to collar, argued that maybe he was more of a simpleton than he’d care to admit.

Something followed him, and if not evil in a supernatural sense, then it followed with evil intent.

Shadows flitted between the trees.

He convinced himself it was only the movement of the foliage on the opposite side of the canal, casting their shadows over the water to his side. It wasn’t much of a theory as the trees on his side were backlit by street lamps, on the far side all was in darkness.

‘Somebody there?’ he demanded.

The instant he spoke he regretted it.

If somebody was lurking, his words might draw them out, and no good could come of it.

He’d heard that the homeless sometimes bedded down around there, using the adjacent woods for shelter. The last Carl wanted was for some drunken wino to accost him and demand money from him in the dark.

He picked up his pace, wobbling as he proceeded on the slippery stones.

The damp atmosphere robbed the sharpness from the slaps of his footsteps. The sounds of distant traffic were muffled.

It was as if his eardrums had compressed.

Something stirred the water.

A fish, a diving bird?

Carl halted, staring down at the murky depths. It was black, and impenetrable. Nothing lived down there in the polluted depths. On the surface there was still sluggish movement, and the meagre light falling through the trees made it look like an oil spill.

Rat, Carl decided.

Yeah, must’ve been a rat. One of those big ol’ water rats that have no fear of cats, dogs or human beings.

He shivered in revulsion.

If there was one thing he hated more than deep, murky water, it was deep, murky, rat-infested water.

He moved on.

A titter arose behind him.

His compressed eardrums flattened the notes, but they still had a feminine quality to them. What kind of woman would be out there in the wee small hours? He immediately thought of the homeless people that made camp across from him, but he doubted any woman chose to hide out in the depths of the woods where she was more vulnerable than ever, not unless she counted herself among

the dangerous ones. Perhaps the laughter arose from the adjacent street, where tipsy revellers wended their ways home, exactly as he did.

The laughter rose again, before it was broken by a series of bubbles and plops.

Carl halted again and leaned over the side of the canal. He swore, because again something had stirred the surface. Did the fucking water rats around here have the voices of sirens, designed to lure the unwary into the filthy water?

Carl snorted at the idea.

But he didn’t turn away.

Something was just below the surface, there beyond the front edge of his vision.

He leaned further, trying to make out what it was that slithered past less than a fingertip’s depth below the surface.

The water settled.

Carl frowned.

His face must have caught an errant beam of light from the street lamps, because reflected on the surface he could see the palest of countenances …

Deep, dark eye sockets.

An open mouth, teeth glistening darkly.

He reared back, croaking in horror.

It wasn’t his face reflected in the oily surface, it was another’s.

He spun, wrenching his hands out of his pockets, about to run.

Something struck him on the back of his skull, sharp and pin-pointed.

It felt like a bullet had pierced his head.

His strength puddled under him as he collapsed.

On his hands and knees, he craned up, trying to see over his shoulder.

Something loomed there in silhouette, holding something aloft that dripped water and slime dredged up from the bottom of the canal … or maybe it was the blood from his shattered skull.

‘You’ve done something very bad …’

Carl’s voice was trapped in his chest, so it wasn’t him that spoke.

An arm rose, and against the faint lamplight were two fingers too sharp to be wholly natural. Each was tipped with a hooked talon. The arm slashed down.

TWO

1988

Hot and sweating, Andy Miller braced his feet on the mound of dirt. Flying ants filled the stifling air; so did other missiles. He swung a stick but usually a second too late behind the clods of earth being hurled up at him. When he did manage to knock aside a divot, it still exploded and covered him in dirt. It was in his hair and up his nostrils, and crumbs of earth had invaded his collar and trickled down his chest. His T-shirt, tucked into his jeans, collected it in the fold of material. Andy tried yanking his shirt free, only to be pelted by more sods.

‘Pack it in, all right?’ he yelled. ‘This isn’t funny.’

‘It is from where we’re standing,’ Carl Butler laughed.

Carl threw another handful of grass and dirt.

‘Pack it in!’ Andy swung pointlessly at the muck. It showered him. ‘Stop chucking stuff. If I go home filthy my mam will go mental and give me a hiding.’

His plea only encouraged his friends. Johnny Wilson crabbed across the field, seeking loose turf to rip from the ground. He hauled back on one divot that was as large as Andy’s body, and if it struck him would probably take his head off. Luckily, Johnny hadn’t the strength to hurl it at him, and Andy took the opening to escape. He leapt down and ran, throwing a few choice insults at the others. Johnny hooted in triumph, and tossed handfuls of dirt after Andy. When he failed to hit his fleeing pal, he turned his missiles on those nearest him. More insults, curses and hysterical laughter pierced the hot air. Andy slowed now he wasn’t the object of torment. One of his friends was on the ground – Johnny probably – and the others piled on top, stuffing dirt and grass inside his trousers. Who needs enemies when he has pals like Carl Butler and Johnny Wilson, Brian Petrie and Gavin Hill?

Abruptly the trio on top launched away, and beyond them Andy watched Johnny scramble up, digging his hands into his waistband and extricating what had been stuffed in his underpants. He chased the others, yelling in mock outrage and chucking the dirt at their backs. Andy joined the pack, running and shouting insults with the best of them. He took it back; his friends were the best any thirteen-year-old boy could wish for.

Somewhere during the race across the field, Johnny caught up, fell in with the others, and joined the pushing and shoving match as they jostled to climb a rickety stile. Brian made it over first, while Gavin and Johnny struggled for room and fell in a tangle of limbs on to Brian. Carl bowed, made a sweep of his arm for Andy to go next: the instant Andy accepted, Carl rushed to beat him over. The boys wrestled for dominance, Carl first to clamber over the wooden steps. On the cinder path alongside the field, they hurtled towards the shortening shadows of the trees ahead.

Another stile was negotiated with similar unnecessary effort and then the group raced through the woods, whooping and hollering. Birds took noisy flight, their wings beating at the foliage. Something larger crashed through the undergrowth, and Andy halted, his breath caught in his throat. He clutched his stick, but what use would it be against a charging beast? What kind of animal large enough to make that racket lived in these woods? He didn’t fancy being charged by a deer with a set of antlers the size of a coat rack.

‘Oww!’ He instantly forgot about the danger posed by woodland creatures, shying away from another jab of Carl’s knuckles in his shoulder. He swung his stick, with no intention ever of hitting his pal. Carl pulled a face, rolling his tongue in his bottom lip.

‘You Mongol,’ Andy called him.

‘You’re not meant to use that word any more,’ Carl countered.

‘You can still say it,’ Andy said, without a trace of irony, ‘cause it’s the name of people from Mongolia.’

‘Do you know what

they call a div in Mongolia?’

‘That’s easy. They call them Carl Butler.’

Carl made the face again, this time adding to its ugliness by crossing his eyes and emitting a moan. Then without warning he launched another jab at Andy’s shoulder, making sharp contact and then charged off. Andy had completely forgotten his reason for halting. Already his friends were a good distance ahead. ‘Hey! Wait for me.’

His pals started chucking things again. This time it was in an attempt at knocking a crow’s nest out of a tree. Andy wasn’t a saint, and not beyond the same senseless destructiveness of other thirteen-year-olds. He snapped his stick over his knee and dropped one end. With a more manageable length in hand, he lobbed it into the tree. He missed the nest and the stick caught on other springier twigs. He shrugged off the miss: besides, his friends were already on the move and he jogged after them. Johnny – lagging behind the others once more – tossed a final handful of pebbles, nowhere near the nest this time, but guaranteed to hit Andy. Andy bit his bottom lip, bent and scooped up a clod of hardened dirt, and threw it at Johnny. ‘One hundred and eighty,’ he crowed when the dirt exploded on his friend’s back.

The boys ran on.

They came to a halt, their progress blocked by a five-bar gate. None of them moved, but stood looking. Beyond the gate there was a shallow valley that ran as straight as an arrow shot. Had it not been for the trees and bushes encroaching on each side Andy might have seen where the decommissioned railway line met the distant horizon. However, the overgrown foliage blocked his gaze within a hundred yards. It was hot, airless, but beneath the canopy of trees existed a microclimate; it was dank and cool and smelled of decay. The old railway lines were now a series of connected ponds and muddy hollows. Reeds stood tall and the murky black water was covered by blankets of green algae and duckweed.

It was weeks since Andy and his friends had last visited the ponds – back then it was to collect frogspawn, now the surviving tadpoles would have hatched, and gone through metamorphosis to froglet, perhaps even to fully fledged frogs. Whatever stage they’d achieved, the boys intended to find them. Carl Butler had designs on any of the amphibians they could capture, and had brought a handful of plastic straws to test his unpleasant plan. The other boys, Andy included, would help with his experiment, whether or not they wanted to. Carl was their friend, but none of them knew why they put up with his bullying.

THREE

Andrew Miller – Present Day

Fear demanded loyalty, as could a blackened eye or split lip. So, it’s not difficult to grasp how I’d fallen into line and followed Carl Butler’s hare-brained and often nasty antics. Within an hour he had us all attempting to inflate frogs by inserting the straws in their bums and then blowing. In hindsight it was a horrible thing to do to the defenceless creatures. As was shooting them from Gavin Hill’s catapult and watching them flail their tiny arms and legs like Kermit from the Muppets, before they smacked into the trees. My friends hooted and hollered in amusement, and to my shame now, I hooted and hollered along with them, despite the nausea in my gut and the sense that the torture we were inflicting was awful and probably wrong.

I’ve often wondered at what age a child is most impressionable, and when a burgeoning serial killer ferments murder in their minds. Small children can be horrible, and they are not beyond torturing their siblings or friends, or tormenting animals, but I think the turning point is at much the same time as when puberty hits. Some thirteen-year-old boys – and girls – can inflate the skin of a frog, pull the legs off a spider, or knock fledgling chicks out of a nest with thrown stones, with glee, and grow more fervent about inflicting pain. Others are sickened and turn away from those acts, often promising to never harm another living creature as long as they live. I’d like to say I’m of the latter category now, but during that hot summer day in 1988 I definitely hadn’t fully discovered such compassion.

The juvenile Andy isn’t the same person as the adult I grew into. I recall his memories, but it’s as if I’m accessing the recollections of a third party, not my younger self. Recollecting the way in which those poor frogs were blown up, skewered on the end of plastic drinking straws stolen from our local Wimpy makes me ashamed, though at the time I laughed as cruelly as the others. Something approaching shame did assail me, but only when I looked up from stomping a froglet to its death in the muck to see a pair of girls watching from the tree-crowned embankment: a Golden Retriever stood at their side, staring balefully at us. The girls’ expressions were more stricken.

Thirty-five years later I squirmed under a similar look of horror. This time I hadn’t been committing frog-icide but was evidently responsible for something my wife found equally disturbing. All I was doing was eating my breakfast.

‘What’s wrong, Nell?’ I asked as I set down my fork.

She didn’t immediately answer. Instead, she pushed her face into her palms, and moaned. I reached across the table and touched her elbow. She drew it away from my touch, raising her head. Her eyes brimmed with tears. ‘Nell,’ I tried once more, ‘what is it?’

‘Aren’t you listening, Andy?’ she sobbed.

‘Listening to …’ Ah, the radio played, tuned to a local channel. As we ate our breakfast it was simply background noise to me, kind of similar to how my wife’s often meaningless breakfast-time chatter didn’t impinge in my thoughts. I don’t know though, perhaps the radio announcer’s words had found a way into my psyche, and was responsible for casting me back to 1988.

‘I don’t believe he’s dead,’ Nell cried.

‘Neither do I,’ I said.

It was difficult to

believe, but Carl Butler, someone I’d once liked and loathed with equal passion, but had always accepted was my friend back then, couldn’t be dead.

The radio announcer claimed that his body had been found by a dog walker, and that he appeared to have been the victim of assault. No specifics were gone into, probably because the police didn’t want to release any evidence they could pursue in the subsequent investigation. It would have been odd enough for them to name the victim, if he hadn’t been found days ago, and his closest relatives already informed of his murder.

Once, I would have learned sooner of his passing, but we’d drifted, parted by the years and a wedge that had been forced between us. There was a time when I could’ve believed the relationship I had with my friends was almost psychic, because we were so familiar with each other that we could read our emotions without asking, could end each other’s sentences only half-muttered, and could sense when the pack was about to move, or run, or even fight if circumstance dictated. Had Carl been murdered back then, I’m pretty sure that young Andy would have sensed his passing, maybe as a stinging pain in the heart, or as a nauseous flipping of his stomach contents, or something else, but adult Andy hadn’t felt a thing.

‘We can’t be certain it’s him,’ I tried, but Nell only wept harder. I tried once more. ‘Surely there are other Carl Butlers living in this city.’

‘In all the years we’ve lived here have you heard of another?’

‘No, but …’ I shut up because I wasn’t helping.

To be honest, I was kind of befuddled, my mind not working properly as I tried to make sense of the news.

Carl couldn’t be dead. He just couldn’t.

And yet, undeniably, I knew that he was.

Not only was he dead, but by all accounts, he’d been beaten to death, murdered.

I stood up from my breakfast. There was no possible way I’d eat it now. But all I did was stand, looking across at Nell, watching her watching me with tears rolling down her cheeks.

‘Why are you upset?’ I wondered, suddenly angered. ‘It isn’t as if you had a kind word for him while he was alive.’

‘How can you say that? Carl was our friend.’

‘No, Nell. Carl was my friend and you never liked him. In fact, you once said you despised him. You wouldn’t let him come to the house, and only ever called him choice names if I mentioned him.’

‘You’re being unfair, Andy. You’re only picking and choosing times that suit your version of events, not mine.’

‘Tell me a time when you welcomed him here, then,’ I said.

‘There were plenty of times,’ she said.

‘I can’t think of a single one.’

‘That’s because you’re confused. You know you get that way. You’ve just had some terrible news, and you’re reacting by lashing out at me! It’s unfair, Andy. You are being unfair to me!’

‘My friend has been murdered, and somehow you manage to make it about you? Jesus-fucking-Christ, Nell!’

She stormed out of

the kitchen. I could hear her muttering and swearing under her breath as she tore through the house, slamming doors and drawers. I allowed her to vent, because yeah, I suppose I had lashed out and maybe I was at fault.

I found my phone where I’d left it on charge and typed Carl’s name into the search bar. Immediately I was rewarded with a list of links to online news sites. Now that the victim had been named by the police, the media wasn’t being shy in sharing photographs of him. Mostly a picture of a smiling Carl Butler was positioned under a shouty grab line. For a few seconds I held on to the hope that this was some other Carl Butler, and that my childhood friend was safe and sound at home. But my wish that another pitiful soul shared his name was dashed the instant I looked at the face in the photos. Back as a thirteen-year-old, Carl had reminded me of a ferret, with his beady eyes and long pointy nose, sticky up blond hair and equally sticky out ears. Over the decades he’d filled out, his face becoming chiselled rather than weaselly, and growing into his ears. His pale hair had receded, and his beady eyes had gained crows-feet to match the deep lines from his cheekbones to his chin. It was Carl all right, somehow managing to make his smile sarcastic, the way he always had as a boy.

‘What happened, Carl?’ I asked. ‘Who did this to you?’

No one answered. No voice from above, out of the ether or anywhere else. The only sound was Nell still calling me names from another room in the house. After a moment she began weeping loudly, and I was unsure if it was at Carl’s demise, or that I’d upset her by shouting. I thought about seeking her out, to apologize, and maybe seek mutual comfort in an embrace, but grief overwhelmed me. It came upon me like a tidal surge that completely submerged me and snatched the oxygen from my lungs. Dropping my phone, I clutched at my shirt front, dragging my collar clear of my throat, but it didn’t help. My knees folded and I sat down, not even aware that I dropped all the way to the floor with my back against the kitchen cupboards.

Tears flowed from me, and my face contorted, and I let out a bellow of denial. I must have cried out several times more, because despite being mad at me, Nell came and she huddled over me, pressing her forehead to mine, and together we grieved, more for our lost daughter, Rebecca, who had drowned during a holiday break in the Alps than for our friend who once boasted that he was going to live forever. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...