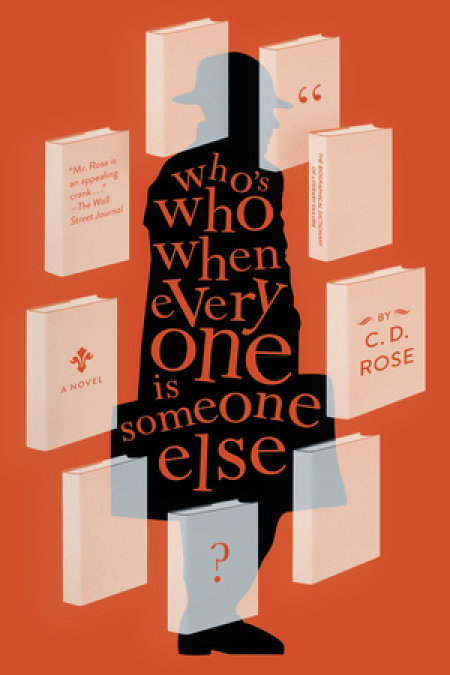

Who’s Who When Everyone is Someone Else

IT WAS A burning morning in late summer when I took my leave of Clara, the sky distant and receding as if in sympathy, the few wisps of cloud that had graced the dawn and reminded me of her hair now scorched away by the sun, already so hot at this hour, at this time of the year. I stood outside the Café Terminus and watched her pass, knowing I would never see her again, knowing our worlds had finally, definitively, utterly separated, and all that would be left of us were improbable names scratched in hotel registers, a bundle of letters bound by a ribbon hidden in the drawer to the left of her bed, and a few bitter tears, long evaporated, leaving only their salty trace on a handkerchief that may, for all I knew, have gone with her. Memories, I should say, memories would last, but I knew she no longer had any, and the few I possessed were treacherous, deceitful, liars to themselves as well as to me.

I sipped the last of my coffee, now little more than a sad black meniscus lining the bottom of the cup as her handsome wooden box passed by, pulled, as her father had insisted, by four fine black horses along the corso then out of town onto the cart track as far as the cemetery which lay a good few kilometres from any living habitation, its own walled and silent kingdom. As she slowly faded from view, I knew I was now, finally, free. Free to take the opposite direction, to turn away from her, from this town, from their whole world.

It was time to take the train.

The station was a tawdry, flyblown little place, scarcely worthy of the name, one platform and a bucket in a shed claiming to be a restroom. Yet it mattered little, as the locomotive appeared on time, entering the town just as Clara would have been leaving it to the other side. While I have to admit that there was a certain grace and pomp in the manner of her departure, train travel, too, has its own romance. The hiss of steam, the burn of coal and grit, the immense breath of the engine as it heaves itself into motion, slowly building to the mighty speed that even such an old chugger as this one could muster. As we passed into open country I listened to the sound of the iron wheels on the steel rails, felt the slow rock of the carriages, watched the land speed by as if I were watching a film. The history of all this, I thought, the knowledge that the rails I travelled on had been forged by honest steelworkers and laid by burly immigrants, that the rock gorge I was now passing through had been hewn by brave engineers laying dynamite with their bare hands. How many had died in the construction of this marvel? The land fell away beneath me, the sound suddenly expanding as we passed over a bridge fashioned from a Roman aqueduct.

But finest of all was the anonymity. Here, I could be anyone I liked. Stepping aboard a train is stepping into a new world. The random strangers. The potential for chance encounter. Once the door is locked and the whistle blown, the departure is total. No one knew me; I knew no one. I could begin again.

I LET THE book drop onto my lap and felt its pages slap shut. I closed my eyes and wished for sleep, but none came. I’d hoped Enrico Cavaletti’s Train to the End of the Night would be the perfect thing to accompany me on a long rail journey and at first the rhythms of the prose dutifully matched the rocking of the train I was on, but soon the long sentences merely bored me and I had to go over them time and again, unable to focus, not for the first time disappointed by the gaping juncture between a book and reality.

I’d turned to Cavaletti on the advice of a friend whose name I was now trying to recall so that I could ignore any future advice from him. “It’s a fine example of train literature,” I remember an indistinct voice telling me, and scribbled Cavaletti’s name in my notebook for future reference only to forget it again until I was embarking on a long rail journey myself. I’d thought of including it on the reading list I was drawing up, too, but on the evidence of its opening passage it seemed little more than a piece of early-twentieth-century schlock, its fancy prose giving away far too much right from the first page. It could go on the reserve list, I supposed.

Sadly, I had nothing else to hand, my only other books stuffed into one of the suitcases now stashed on a dangerously narrow overhead luggage rack. To get it down and open it up would have meant disturbing my fellow passengers, none of whom seemed the types to be disturbed without annoyance. I stared out of the window instead, and thought about how it wasn’t the gap between the book and reality that had disappointed me, but rather my failure to allow what I had been reading to change the world I was in.

The world I was in at that point was a packed train now three hours late due to an unexplained and interminable stop in the middle of flat empty fields somewhere just over the border between two countries, neither of which I knew the first thing about. I was squashed into a back-aching seat next to a man who had the air of a distracted philosophy professor, and seemed to be sleeping off a heavy lunch. Across from me, another man was attempting to engage the other members of our compartment in conversation, but the two young women were content to whisper to each other and ignore him, while the final occupant, a nun of some order unknown to me, only nodded whenever he spoke to her and said not a word. Fortunately, as long as I read or pretended to read, I maintained the force field of the book-absorbed foreigner, one which no one attempted to break.

After what felt like several hours—but I concede may have been fewer—the train began again, slowly enough to let a few grey storage hangars emerge from the fog but rising to a steady trundle through a cluster of unimpressive tower blocks, which in turn gave way to spreading leafy suburbs before sinking into a tunnel of near-Stygian gloom, its brick and cement walls seeming remarkably free of graffiti. The tunnel then opened out into a glass-domed space, all light and iron tracery, pigeons swooping around the crosswork beams. A platform hove up alongside us as the train slowed, the film finishing. An ornate fin-de-siècle sign announced the name of our city, and the word “Terminus.” The end.

AND SO I had arrived, a man in a battered hat with a bulky suitcase in each hand, suffering under an overcoat too heavy for the weather. I could have been that eternal migrant, the one slowly fleeing from some domestic turmoil, the man who’d shifted from city to city for years, ever seeking a point or purpose in each one. I could have been an autodidact peasant, now come to the city to show off his learning, pronounce a great theory of everything or a new path to spiritual enlightenment to rapt crowds in packed halls. Had I been younger, I could have been the eager naïf at the beginning of a cheap musical, ready to put his cases on the pavement, stand up, stretch his back, whistle through his teeth and sigh, So, big city—whaddya got in store for me?

I was, in truth, none of these things, yet also a little part of each of them.

But perhaps I should explain.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved