1

ONE AFTERNOON last October, on the concrete of her patio garden, my mother had a fall.

The event replays itself in my memory like an old reel of film. The picture wavers; the perspective shifts; the quality wanes. At the time, I had a clear-eyed view of her. She was so distinct from her surroundings. But not now. Now, watching the film my mind has made, my mother’s features blend with everything behind her: the shadows, the lawn, the sepia sky.

She was out there because, at the age of eighty, she woke each morning with one ambition: to keep that patio clear of weeds. Weeds kept growing between the slabs of concrete, and she kept pulling them up. Responsibility for the upkeep lay with the warden, but this made no difference to my mother. The warden was shooed away and, when I offered help, I was told to stay indoors. So that’s what I did. I sat in her front room at Finegold Mews, drinking. Outside, it was a crisply lit autumn day. A sliding glass door stood between us and a thin beam of light lasered its way through, falling into the tumbler in my hand, making the ice cubes tremble. The only sounds I could hear were low-level corridor noise: the hum and whine of other residents shuffling along, dropping things, picking them up.

It was the thud, the first of two, that caught my attention. I was watching the light melt the ice when I heard it. I looked up, and immediately saw the danger she was in. The

palm of her hand was squashed against the glass door. Her whole weight seemed to be behind it. Her fingertips, first dark grey, then light grey, slipped and squeaked. I stood up and shouted, ‘Mother!’. For decades I had addressed her as ‘Mum’, but it was the word ‘Mother’ that knotted in my throat and unravelled in the room. Since her death, it’s become the thing to say.

The seconds that followed form a series of staccato, black-and-white shots. She is drifting. Narrow shaken shoulders. Raised brows and fallen eyes. Neck delicately twisted. And the veiny hand. Only this disembodied alien, shrivelled and pockmarked, holding her up. Fingers, inching downward, until she seems certain to fall.

But then the scene changes. The hand stops sliding. Improbable, but it is off the glass completely, dropping, like a weathered stone, into the front pocket of her apron. She regains her composure and balance. She swallows, turns her face up to the sky, takes a big breath. It’s a proud, defensive posture. Only the blackbird overhead can see how thin her hair is.

By the time the second thud came, she appeared almost safe. Looking back now, it is this moment, in which it seemed crisis had been averted, that was the crucial one. I stood in her front room looking through the glass door, the drink still in my hand. I could have walked five yards, slid the door open and brought her inside. Or, if she wouldn’t be reasoned with, taking me for some troublemaking stranger, I could have reached for one of the little orange triangles dangling from pull cords. One of those, or that emergency button on the wall. A forty-one-year-old man can lunge for a triangle or a button without breaking a sweat. For an instant, I could have done any of these things.

I linger there, in that still moment, because it is the last time I really had any options.

—

How did I even get there, in a position to watch her suffer? Minutes before it happened, I was in the kitchen. I was clinking ice into a glass.

She walked in and took her gardening gloves from a drawer labelled ‘garden things’, but was oblivious to me downing two glasses of butterscotch schnapps, the only drink I could find, and swallowing three pink pills. Since the dementia set in, she was oblivious to most things.

She took her gloves into the front room. I poured a final schnapps, put the bottle back, and started looking for a snack. There was nothing useful to be found. You could tell that she had built a life for herself in the post-war years. The ‘remedies’ cupboard was packed with Milk of Magnesia, Vicks VapoRub, Fynnon Salts, Friar’s Balsam, Germolene. There was a section of the fridge labelled ‘rationed’, stuffed full of butter, lard, margarine, cheese, eggs. A little storeroom off the hallway (labelled ‘storeroom’) housed precarious columns of tinned goods – fish, tomatoes, meat, soup, vegetables, treacle. Alongside the tins, sugar (caster, icing, demerara), flour (plain, pastry, self-raising), lentils, pasta, rice. Then there were the latticed jars of fruit preserve, the boxes of Braeburns and Bramleys, the bottles of squash. My mother had been acquainted with shortage, and she didn’t forget it.

As I settled down on the leather sofa with my drink, the smell of meals on wheels in the communal corridor drifted in. I remembered that I hadn’t eaten all day. I was so anxious about leaving my place that morning, about

facing the dangers that crowd the world outside my flat, I couldn’t manage any breakfast.

‘Why don’t you let me do it?’ I said. She was hobbling across the carpet in the direction of the glass door. ‘Why don’t you let me pull up the weeds, if you’re that bothered?’

She didn’t respond. Instead, apparently remembering something crucial, she took a sidestep toward the television set in the corner. It was a clunky old thing, a throwback to a time when pictures didn’t matter so much. She steadied herself on one of its blunt corners, reached around the back, and pulled out a shoebox. She placed the shoebox on top of the set, gave it a friendly pat and made her way over to the patio.

I said, ‘What’s in the box, Mum?’

She slid the door open with a colossal effort, then paused for a long time, considered my question. Cold air riddled the room. Then she responded. I remember the exact words she used. In the time that has passed, they have echoed through my mind with greater and greater resonance.

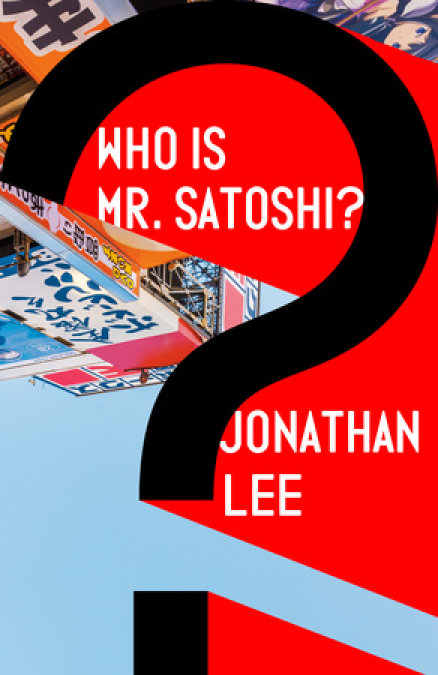

She said, ‘The plan is to deliver it to Mr Satoshi.’

‘Who’s Mr Satoshi?’ I said.

And she said, ‘Most of all, the package is for Mr Satoshi. For when we get an address for him.’

Her voice was soft, but I heard each word quite distinctly. Then, her grip on the door handle suddenly fierce, as if someone unseen were dragging her outside, she said, ‘And if you’ve got any influence around here, you’ll see to it that the warden keeps off my back.’

She slid the door closed behind her and I sank back into a clump of cushions. The gardening gloves lay dejected at my side.

A heartbeat later, as I was swirling my sickly schnapps in the beam of afternoon light, I heard it. The thud. The air was clubbed flat by it. I was surprised that someone so tiny could generate such a sound, and for a second I thought the window might give. I stood to attention, but it stayed in place, her hand still suckered to it. White and sticky and pressing hard. Her head dipping, her body crumpling, her hand sliding downward. And then the recovery – the miraculous recovery – the straightening up, the chin to the sky, the hand off the glass.

One tick of a clock is all it takes for your options to evaporate.

—

The crucial moment. I felt my heart beating hard in my head. My mouth was suddenly dry, the corrosive fizz of a pink pill charring some hidden tract or tissue in my throat. But I ignored these signs. I wanted to believe that the scare was over. In that empty second, that blank space in time, I knew I had choices. But I convinced myself, I must surely have convinced myself, that there was no need to act. Why else would I have stood there, so rooted to the spot, as she – confident in her own recovery – leaned in again, determined to get it, determined to pluck the rogue dandelion from a gap between two concrete squares?

She wiped her hands on the front of her apron and dipped lower, much lower than before, attacking the perennial scourge of her nice, neat, paved grid. In murky greyscale, as I see things now, she is hunched over a huge chessboard. And then it comes. I see it. I see that the stalk she is clutching isn’t lifting. The dandelion’s roots, wide-spreading and thick,

won’t budge from the hard-packed soil. The unsteadiness is all hers.

This time the thud was not from her hand, but her shoulder. It hurtled into the glass door. It slid. Her knees buckled as she succumbed to the gravitational pull of the weed. It drew her into an irresistible downward trajectory.

I doubt she had time to notice, as she accelerated toward the ground, how beautiful the bulbous seed head of the dandelion looked. Its fine, snowflake strands were spectacular. At first those strands held firm in one tight ball on top of the stem. Then they disappeared from view completely, obscured by her shadow spreading across the patio. But, on impact, the seeds burst out from the darkness. They exploded. A firework of bright white atoms, a magnesium flash that burns the image onto film.

And I didn’t hear her head strike the concrete. I heard silence punctured by my own short, horrified laugh. I waded toward the window. I dropped my glass along the way. Instead of cracking, it bounced absurdly. Outside, thin wisps of October cloud thickened in the lowering sky. They drew a veil of grey across the garden. She lay there in a craggy heap. Her hand twitched mechanically and I let out a stupid whimper. The apron had gathered around her neck, and her spent face peeped over the top. Black blood drizzled from her one visible ear.

I stood there until I was sure that she was dead. I pressed myself right up to the glass. My forehead flat against it, my hands too, eyes shuttered, and I stayed there for a long time, collapsed against the cold surface, let it take my weight completely. At some point, it started to rain. I went back to the sofa and sat there, watching translucent drops randomly merge and run jerkily downward. A pool of murky water

formed around the body. If I close my eyes now, I can still see that water, a drama of reflected cloud, channelled into the soft grey glow of a camera lens.

Eventually, after taking more medication, I called the emergency people. When they came knocking I felt, just for a moment, that it was Mr Satoshi at the door.

It wasn’t, of course. All that was waiting for me was the thick green rush of paramedics. Pretty soon I couldn’t see my mother at all. The tightly assembled strangers put her on a stretcher and covered her with a cotton sheet.

Her face has remained veiled ever since.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved