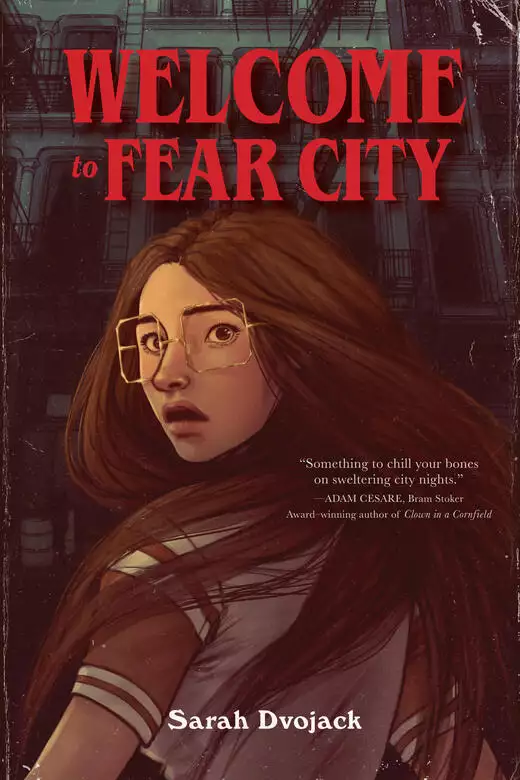

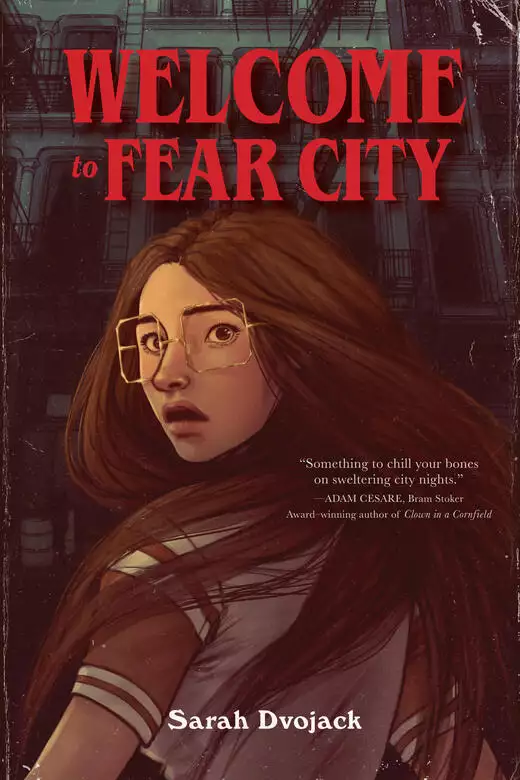

Welcome to Fear City

- eBook

- Paperback

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

New York City, summer of '77—in a city on the edge and obsessed with a serial killer, Sylvie Stroud is dealing with an entirely different kind of evil when she awakens a dark magic hellbent on consuming her.

Seventeen-year-old Sylvie Stroud can see the past of any building just by touching it. Her powers have always been reliable, until one day she sees the memory of a teenage girl’s murder without touching anything at all. There's a lot of violence in New York City, especially in 1977, but this is different. When the vision keeps repeating, Sylvie begins to investigate. But doing so accidentally awakens an old, parasitic magic lurking just beneath the surface of her beleaguered city. Now all it wants is Sylvie, and it will go through everyone Sylvie loves to have her.

This page-turning horror novel, complete with 22 black and white graphic novel pages throughout, is perfect for fans of Stephanie Perkins and Kendare Blake.

Release date: September 3, 2024

Publisher: Union Square & Co.

Print pages: 432

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Welcome to Fear City

Sarah Dvojack

THE CAST-IRON DISTRICT

HELL’S HUNDRED ACRES

SOUTH HOUSTON INDUSTRIAL AREA

“SOHO”

November 9th, 1965

Sylvie Stroud was watching an episode of Where the Action Is. At five years old, she was hopped up on the day’s top hits as they piped through the old black-and-white set, dancing wildly within the confines of the woven rug beneath her bare feet. (Stray one toe outside of it, and you were sure to get a splinter from the old floor.)

As Little Richard ended his performance and the jerking teenagers on the screen stopped to clap and screech, the screen began to flicker. Sylvie didn’t notice it, but even if she had, it wouldn’t have bothered her. The TV was forever doing funny things like that, both because it was ten years old, and because the loft didn’t have reliable electricity.

She was home alone—in a way. Her dad and brother were out, but her mom was downstairs in the other studio reupholstering a chair they’d fished from an industrial dumpster. Sylvie could hear her radio through the thin floorboards, so she started dancing to that instead. Hey, you, get off of my cloud!

But then the TV started spitting out incomprehensible garbage, and Sylvie turned to see the image whirring whirring whirring at a frenetic pace until, with a soft pop, the screen went black. And with it went all the lights, and the sound of her mom’s radio. Sylvie could see her surprised face in the smudged glass of the TV set, lit up now only by the moonlight coming through the tall windows.

Sometimes that happened, too, when the old fuses couldn’t take the pressure. But there was something different about it this time because Sylvie quickly realized that moonlight was all there was. The buildings across narrow Greene Street were as dark as her own, including the factory that made cheap plastic dolls and women’s underwear.

Outside, an empty truck rattled by and people on the sidewalks called to each other. You seein’ this? What in the hell!

All the warmth from her dancing left her very quickly. Her skin felt like it was buzzing, all the hairs on her arms shivering. The silence was so thick that it was loud inside her head. And the rest of the unfinished loft was dark and deep as a cave—Sylvie had never noticed that before. It had always seemed bright and open.

A tickling sensation on her foot made her jump, and she looked down to see a couple of ants crawling over her toes. Like everything else, that didn’t surprise her, either—the building had holes and cracks at every seam, and rats still kept a functioning highway between the floors.

It had been at least two minutes and her mom hadn’t come upstairs and Sylvie didn’t want to be sort-of-home-alone anymore.

She sat down to brush off the ants and pull on her socks, and when she got back up again, she put her bare hand down on the floorboards for leverage.

All at once, she wasn’t alone anymore. A whole entire world burst into her own. Instead of furniture and art and stacks of sheetrock, there were machines and noises and the foulest smells. Old oil and dirty fabric and rancid smoke and things she had absolutely no names for because she was only five years old.

People wearing old, unfamiliar clothes marched into and over each other, talking and laughing and yelling in equal measure as they moved through and around piles of acrid furs or thundering machines. The floor was covered in discarded waste all knotted together. Were those boxes of buttons? No. Piles of fabric? Mounds of wool? Her street was still covered in bales of fabric and clippings, but not in here! Like staring at ten slides all stacked up and held to the light, the images didn’t make sense. She was frozen in the middle of it, unable to move for shock. The moon glowed through the people, turning them to ghosts. They had to be ghosts. Her house was haunted.

She shut her eyes.

The people disappeared when she ran, screaming, for her mother, her sock-covered feet beating a path to the door—a path that these strange people had already taken. Were probably the reason the floor was so worn out in the first place.

She couldn’t explain what had happened, so she pretended she had been afraid of the dark, and her mom believed her.

But then she made the mistake of touching the windows to see down into the dark street, and all the ghosts erupted from the walls again. This was how Sylvie learned that they only showed up if she touched the old parts of her building. The windows, the floor, the exposed brick walls. Then she learned that objects held ghosts, too, even the old typewriter her dad found sitting on a curb (there had been a note taped to it—NOT BROKEN). Several ladies in shirtwaists typed when Sylvie typed, so Sylvie never used it again.

She wore mittens indoors and her parents laughed it off because it was nearly winter, and the loft was cold. But she wouldn’t take off the mittens at school, and she wouldn’t take them off in bed, and when her parents fixed the boiler, she wouldn’t take them off then, either. Every surface was a perpetual game of hot lava, but she appeared to really believe it would burn her.

By spring, she was in front of an NYU psychoanalyst, her now six-year-old mind trying to come up with a lie because she didn’t understand the truth but knew it was too unbelievable to convey. He said she would probably grow out of this behavior, that kids sometimes developed anxiety around starting school, but he still looked at her funny and she still had to see him every other Wednesday.

Forced to think about it, she began to wonder—if these were ghosts, shouldn’t others see them when she did? Why weren’t they lurking under her bed or shouting “BOO!” from dark corners? They never even looked at her.

In the fall, she went on a field trip to the Metropolitan Museum of Art with her first-grade class and leaned against a pillar in the patio from the Castillo de Vélez-Blanco. A mere sliver of her wrist brushed the marble—and as both a Spanish castle and a Park Avenue mansion suddenly overlaid the staid museum, Sylvie realized that she wasn’t seeing ghosts at all.

She was seeing the past.

Almost immediately filled with relief, she wanted to tell everyone she knew, but her teacher simply praised her vivid imagination and joked with the chaperones about some ladies who time-traveled at Versailles.

Not being afraid didn’t make it any easier to endure the chaotic mess that is the passage of time. She was sick of wearing mittens and sick of going to the analyst. When she read X-Men comics with her older brother, she thought of the young mutants who could control the uncontrollable and decided to figure out how to sort the pile of slides into an orderly projection that could be switched on and off when she wanted.

It took years, but it worked, and she learned a lot about her powers as she spent all her time with them. When she began to need glasses, she called the power her 20/20—because her hindsight was particularly good.

She learned that she couldn’t use it on living things, like people. She learned that history had to steep for something near a decade before she could consume it, so new objects gave up nothing. She learned that she couldn’t interact or change anything, and that no one could interact with her. She even learned how to focus on one memory at a time (it helped to know what you were looking for). More and more she thought of the visions, the memories, the slides, as movies to be preserved.

Because once obliterated, some memories were lost for good. She couldn’t find Collect Pond or even an inch of pre-European Manhattan underneath all the concrete and steel. When she watched West Side Story, her parents told her the neighborhood was beneath Lincoln Center. When she learned that Penn Station was finally getting demolished, she made her parents take her there nearly every weekend, and she would prowl the exterior, trying to collect stories that were about to be thrown away, writing things down in notebooks she refused to let anyone read, though her brother often tried.

Her own neighborhood was as vulnerable as Penn Station and San Juan Hill. While the adults organized, she wrote furious letters to Robert Moses like it was a hobby. Her dad found one and hung it at a gallery opening. An art dealer bought it for $50 and turned it into a mimeo that was spread around the neighborhood, then into the Village and beyond: ROBERT MOSES STOP PUTTING ROADS THROUGH OUR HOMES!!!

After four years, she stopped wearing mittens (even in winter) because she could finally move through the world like other kids again, putting her bare hands and bare feet wherever she pleased and only seeing things when she felt like it.

By the time she was ten, she had been kicked out of every museum in the city because she couldn’t (wouldn’t) stop touching everything. She was banned from school trips until her parents explained that the oils from her skin could damage old things. (They wondered if touching too much was compensating for all those years in the mittens, but they stopped taking her to the shrink.)

Of course, she didn’t keep it to herself, but still no one believed her. She pretended to be a reverse psychic, able to tell anyone anything about their school building as long as it happened years ago. She made two dollars doing it, but a teacher stopped her, asked her how Encyclopedia Stroud knew all that.

Oh, I just touch the building and it shows me.

It gave her a sense of ownership of her city that no one else could have. She made a game of looking through old photographs at the public library her mom worked at. She would find a famous face, a famous event, and scour the past to find them. She learned how much of New York was reused, some buildings on their fifth or fiftieth iteration. Square pegs in round holes, either chopping off their corners or crudely busting out more space (like her neighborhood). Some buildings wore their history proudly. Others covered it up.

For years she would peek at every building she passed, creating parades of moments around her like episodes of TV, seeing everything without fully comprehending how real it all had been, despite the smells, despite the sounds. Too young to grapple with the ugly parts, until she wasn’t anymore.

The history in and around her neighborhood had its own particularly bitter flavor, full of dregs. Rat pits and frozen bodies. A man sleeping on the steaming corpse of a horse and children keeping warm on a grate. A family thrown from their apartment, their possessions already on the sidewalk, the children thin with bellies distended. Gangs of men shooting and slashing at each other—several with their innards spilling out or blood gushing from their necks and gasping mouths. Police raiding brothels and dragging women down the steps. Black men beaten by raging white men. The kidnapping of a scarlet-haired dancer from the ghost of a Bowery theatre, her head—identifiable only by that scarlet hair—dumped where an old wood-frame house used to be. An unconscious girl Sylvie’s age hauled onto a cart and carried away. A woman with sharpened teeth picking flesh from long, brass nails on the tips of her fingers. Fires. So many fires. Young women falling from the sky to escape a raging inferno that burned Sylvie’s skin and hair and filled her nostrils as though it were still happening.

In the sixth grade, Sylvie kept her hands to herself for almost an entire year. For months, she had night terrors. It was back to the analyst, where she decided she couldn’t be so adventurous or so callous. Her focus shifted to the present, to dance class and crushes, to the only friends who actually believed her. She visited the same places and always vetted new ones, letting go of the idea that she could learn everything buried in the surfaces around her, realizing that no one could.

The country thought her city was dying, but Sylvie knew it couldn’t. She could see through Manhattan, right to its beating heart.

At least, she thought there was a heart there.

May 30th, 1977

The gunshot severed the scream.

A teenage girl hit the sidewalk and collapsed over the curb, into the street. Her splayed arms nearly flung beneath the wheels of a Ford Pinto.

The Pinto didn’t sound its horn. A nearby dog-walker didn’t flinch, nor did her little Pomeranian.

Sure, this was Hell’s Kitchen, but unless the Westies and Gambinos had changed their targets, there was no reason for a teenage girl to be shot during the dinner rush on a Monday evening. There was less of a reason for no one to care about it.

The Post would probably say this was the moment the City of New York finally lost the battle for its soul. Earth to city: GIRL DROPS DEAD.

If, in fact, a teenage girl had been shot at all.

Her body was already gone.

Sylvie’s heart thudded in her ears, pumping her head so full of blood that it felt like her brain was being smothered. She gripped her dance duffel and tripped down the last two steps of the row house stoop. Her knee hit the iron gate, chipping off bits of black paint and knocking the small, wooden sign affixed to the rungs: BYRNE SCHOOL OF IRISH DANCE.

“Wow, Sylvie,” said one of the girls coming up behind her. Nessa Murray, of strawberry hair and a pale face full of freckles and erythema. “You gotta open it first.”

Sylvie couldn’t think of a reply.

The accordion music began again, two floors up, proudly striding out an open window, while the rest of her dance class dispersed over the sidewalk. A few of them waved to a pair of girls smoking by a scraggly but determined tree.

Sylvie didn’t even feel the impact of the gate on her knee. She had to keep moving, had to spread the block between herself and whatever that was. Whatever that was, wasn’t supposed to happen. Sylvie thought she knew how it worked, the palimpsest that only she could read.

After all these years, she didn’t want to be wrong.

The two girls by the tree flicked their cigarettes away and dropped beside her. Marzelline Hallan, a Black girl with her hair in braids she’d done during homeroom, moved her eyebrows in different directions and folded her arms. Her leather jacket squeaked at the elbows. In that moment, she was the epitome of skepticism and looked exactly like her contralto mother, rather than the soprano who fronted a punk band. (It was the formation of that punk band that had Marzelline switching out her nickname from Lina to Marz. Marz and the Martians. Her opera diva mom hated it.)

“Hello to you, too,” said Marz. “Where’s the fire?”

“I thought I forgot my hardshoes for a sec,” Sylvie said, rescuing her voice from her bone-dry throat. “So, did you find a new drummer?”

On Sylvie’s other side, Marybeth Huang laughed, though it came out as a snort that seemed rather undignified coming from someone in a gleaming ballet bun and pink tights.

“Smooth,” said Marz. “Subject expertly changed.”

Talk through it, Sylvie. “I’m not changing the subject; I’m making conversation.”

Marz looked at Sylvie in astonishment. “Okay, babe. Sure. No, I didn’t find a new drummer in the last two hours.”

Sylvie hugged the strap of her duffel harder. “Sorry for asking! Damn.”

“Now why are you getting all shitty?”

Marybeth looked down at Sylvie’s leg. “You just fell down the stairs. Did you notice?”

When Sylvie didn’t answer, Marz took hold of her ponytail and tugged it once.

“Space.”

Twice.

“Ca-”

Three times.

“-det.”

Sylvie grabbed her ponytail back. “It’s—”

CRACK

Sylvie’s entire body jolted, and she spun around to see the teenage girl already prone on the ground. With no car in the way this time, the scene continued to play, and Sylvie couldn’t stop watching it.

The girl wasn’t dead at all. She clawed at the ground, dragging herself forward with one arm, heedless of the road in front of her and the people walking by. The people walking right through her. From this distance, Sylvie couldn’t see the girl’s face, but she noticed how something grabbed her hair and began pulling her back. And as it pulled, her body faded and was gone again.

She had never seen anything so clear before, so isolated. It was sickening to behold.

“Sylvie?” said Marybeth, who actually sounded concerned now.

Sylvie’s gaze flickered from Marybeth and back to the empty sidewalk, where the ground floor of a row house had recently been gutted to make way for some sort of something. A café, one of the dance moms said. A sure sign of either money laundering or the next wave of neighborhood reform, or both.

In the minutes that had passed since the gunshot, since the girl, since the Pinto, since the Pomeranian, no one had even looked out their apartment windows on the top three floors of the maybe-café, where the girl had fled, and screamed, and been shot all at once.

Sylvie felt sick and cold. She readjusted her bags. “I gotta get home for dinner.”

Marz leaned over to close the space between the three friends.

“Hey, I’m serious, what’s going on?”

“Nothing!”

“Did you, like, see something?” Marybeth whispered as they restarted their walk to the train.

“Because you got that look,” finished Marz.

Sylvie shook her head and untied her ponytail. A sheet of long, tangled brown hair hung around her face. “Forget it.”

“Why are you hiding?”

“I’m not!”

But Marz nudged her to the side, until Sylvie was pressed against the iron fence of the nearest apartment building. Flies buzzed around the garbage bins. Ants had control of a banana peel.

“Stop—damn!” Sylvie protested.

“Tell us or else.”

“Or else what?”

“I don’t know—you’ll feel guilty? C’mon, you saw something! Did you finally look at Deirdre’s cellar? Was that book right about the crazy doctor who butchered his patients? Is there a for real ghost? Sorry if so. I didn’t actually believe it.”

Part of their friendship was spent looking up haunted houses to confirm or deny their apocryphal origins, Marz’s second favorite pastime after music. They looked for places easy to vet, easy to research, but were rarely ever successful, and nothing was ever scary. They started that hobby in junior high, with the old Merchant’s House Museum near Marz’s place.

Sylvie pushed her hair over her shoulder and squared off with her. “You gave up your chance to find out when you gave up your chance to be the first Black Irish dancer in New York.”

“I made my choice, girl. I see what you wear and it’s not decent.”

“Oh, it’s not so bad,” said Marybeth, who had joined Irish dance lessons with Sylvie before committing to ballet.

“Okay, Miss Tutus,” countered Marz.

Dance was a topic Sylvie could run along like a track, so run along it she did. Anything to put distance between herself and the probable murder tumbling around her brain. “I’m getting a new dress this summer. What would you approve of, Marzy? Should it be leather and safety pins?”

Marz made a scoffing noise.

Marybeth laughed. “No, no, Sylvie. Disco, Marz’s favorite-and-a-half ! Make it gold lamé!”

Marz sighed. “I’m not the one who’ll be wearing it in front of people.”

Sylvie ignored her. “Ooh, totally! Sequins all over.”

“Just covered in rhinestones,” said Marybeth.

“Ah, rhinestones. The most Irish of stones,” said Marz. “Blarney, Swarovski …”

Sylvie interrupted her. “I’ve told you a hundred times. Being Irish doesn’t even matter. My parents aren’t Irish, and Marilyn is … I guess I’ve never asked her.”

“Real talk, babe, I probably am Irish—”

“We are so far off the point, guys,” Marybeth interrupted. “What did you see? You know we’ll believe you.”

It wasn’t a question of belief. It was a question of acknowledgment. Acknowledgment that maybe her powers were going wrong. But there was no reason to lie, either. She would tell her friends eventually. They were the only people she could tell.

“Okay. Look. I saw something, and it was weird, but the weird stuff isn’t the weird part—I shouldn’t have seen it at all. I didn’t touch anything!”

“You ran into the gate,” said Marz.

“That doesn’t count,” said Sylvie. “Anyway, see these jeans covering my legs?”

“Oh, she’s a bitch today!”

“It’s hard to—to always know what you know,” said Marybeth.

“What was it?” asked Marz.

Sylvie sighed and lowered her voice. “Some girl got shot. But it was across the street from Deirdre’s.”

Marz turned her head as though she would see the body, but she knew enough by now to realize she wouldn’t see anything. She knew enough because there wasn’t all that much to know.

Unlike in the comics Sylvie and her brother used to read, there wasn’t a mad scientist or celestial being she could turn to for help. No mystical tome, vat of radioactive insects, or faraway galaxy to explain her origins. Even her adoption was wide open. Her birth mom, Marilyn, having been a student at the Brooklyn high school where Sylvie’s mom once worked, was now a journalist or something on the other side of the city. They usually saw her at Christmas. Not exactly a mystery.

“You don’t think …” Marz bit her lip.

Sylvie waited half a second before pushing Marz’s shoulder. “What? You don’t think what?”

“What if it’s, like, something to do with the .44 caliber killer.”

“What?” said Marybeth.

“How?” said Sylvie.

Marz threw out her arms. “He shoots people, right? College girls!”

“Yeah, in Queens outside discos, not in Manhattan outside Irish dance schools.”

“If he heard all that accordion music …”

Sylvie sighed. “Okay, Don Rickles.”

“He can’t take the train?”

“Don Rickles?”

“The shooter!” Marz looked over her shoulder to be sure no one was paying her attention. “I mean, people been shot here, too. Shot and bombed. And bombed again. Dunno why your teacher doesn’t move.”

“She grew up here.”

“I’m just saying, it’s not out of the realm of possibility some multiple murderer would come over here. Maybe it’s too hot for him out there. Or, shit, maybe it’s a copycat.”

“Ugh, Marz, stop,” said Marybeth. “You’re creeping me out. My studio’s over here, too.”

“I should quit meeting you dance nerds and stay home. Anyway, Sylvie, what d’you think? Maybe it’s some astral-projecting ghost of his victim!”

Sylvie shook her head as though to push the words away from her. “No way, bub. I’m not psychic. Whatever happened already happened, and it must’ve happened years ago. That’s how it’s …” Sylvie trailed off. Did any of her rules, her observations of her own abilities, even matter now? Maybe it was from yesterday. Maybe it was a girl who liked to dress a little retro, like Elvis fans her age.

Marz sighed this time, tapping her bitten nails against a scratched-up New York Dolls badge on her lapel. “The bigger mystery is how you saw her at all, right? She was at one place, you were at another.”

“Maybe I didn’t drink enough water.”

“I feel ya, I feel ya. That’s gotta be it.”

“Maybe it’s something different. Maybe it has nothing to do with the normal stuff you see. You know how people say some kinds of ghosts repeat their lives and don’t know they’re dead? Maybe it’s that,” said Marybeth.

“Yo, that’s not a bad theory!”

“See, I listen to you, ghost nerd,” said Marybeth.

Sylvie was grateful for the hypothesizing, really, and almost didn’t want to poke holes in the idea. But. “But you didn’t see anything—or hear anything? I heard a gunshot. And she screamed.”

Despite herself, despite everything she knew, Sylvie hoped.

But Marybeth shook her head.

And Marz did, too. “Man, I wish you could record it and we could see what it’s like. Not—not the murder!” (Sylvie had looked at her.) “Just your visions.”

The weight of her bags was pulling at knots in Sylvie’s shoulders, so she sped up.

Her friends were quick on her heels. Marz began walking backward in front of her, her worn-out Chucks expertly navigating the broken sidewalks and oncoming foot traffic. “Okay, so you’ve never asked Marilyn about being Irish, but have you ever asked her about … your powers?”

Sylvie snorted at the word powers. She couldn’t help it. It sounded so grand and so important and also plain-old-fashioned ridiculous. If she were in X-Men, she would be Random Background Student. “I’ve thought about it, but I’ve also thought she might tell me something else. Like, her whole family’s nuts or something.”

“Obviously you’re nuts, but you could still have powers.”

“Thanks, bub.”

“You should ask her. It’s not like she’d ask you. Probably for the same reason, y’know?” said Marybeth.

Sylvie sighed. “Maybe she fell in the Gowanus Canal when she was pregnant. That’s sorta like a vat of radioactive goo.”

Marz looked Sylvie up and down. “It woulda been so ironic if you were the first Irish dancer with, like, ten arms.”

Despite herself, Sylvie laughed.

Sylvie and Marz once lived in facing cast-iron warehouses on either side of Greene Street. Along with Marybeth, who lived around the corner on Broome, they were three of the few children in all of SoHo because, at the time, no one was supposed to be living in SoHo at all. When the threat of the expressway became too real, Marz’s family moved into an East Village townhouse.

But all three girls still attended the same schools, and Marz’s dad still owned their Greene Street loft. He even played freeform jazz there on the weekends, or at Ali’s Alley, like the old days. Sometimes Marz’s mom would practice her arias there, too. Loft opera, Marz’s dad called it. Then they would all go to FOOD on Prince Street and have the soup, even though the prices went up once the tourists arrived in the neighborhood. People constantly worried that SoHo’s future was already lost, the artists’ days numbered in favor of uptown or out-of-town yuppie bohemians in Earth Shoes. But Sylvie thought the adults were freaking out for no reason. There were still too many rats and trucks in the streets.

Marybeth’s family had called this part of the city home for almost a hundred years. Her great-grandfather opened the first electric light shop on Canal Street. Her father was an installation artist who used neon bulbs. Their loft was twice the size of Sylvie’s in order to have enough room.

They were all rooted to the mercantile wasteland, addicted to the space, to the DIY spirit of organizing and self-expression. Defeating Robert Moses was a point of pride and deepest honor.

With the threat of demolition and illegal living no longer looming over them, it was hard to imagine going anywhere else. Even when Sylvie’s mom lost her job when the city closed her library and her dad, fearing layoffs, jumped from CUNY to teach at the School of Visual Arts. Her parents were raised in Brooklyn (her mom) and the Bronx (her dad), but they liked charting this strange new/old cobbled ground. Her mom got into ceramics.

With Marz on a crosstown bus for home, Marybeth and Sylvie walked together from the train and parted ways at Sylvie’s door.

“Chin up, kiddo,” said Marybeth. “We’ll figure it out. Don’t worry about tonight.”

“I won’t.” Sylvie hoped it wasn’t a lie. “See ya tomorrow.”

“Later days.” Marybeth waved, then had to wave a second time when a neighbor spotted her across the street. An older lady whose paintings of melting pet portraits were always in the Prince Street art fair. Sylvie waved, too, then she turned around and took out the keys to get inside. One for the street door, another for the elevator, and two more for the apartment. She would only need the deadbolt since her parents were home.

Geneva Stroud was surrounded by steam heat from a pot of something on the stove. Her thick, dark hair slowly falling out of the twist pinned with sticks at the top of her head.

“Woo!” She waved her hand through the cloud and moved away from the burners.

Stepping out of the elevator, Sylvie dumped her bags on the unvarnished floor and wrenched off her sneakers as her six-year-old golden retriever ran, tongue out, from the other side of the loft.

Sylvie scoured her fingers through fistfuls of her dog’s warm fur. “Hi, Jessie Baby!”

“How was class?” asked Sylvie’s mom.

As Jessie Baby ran circles around the brand-new kitchen island, Sylvie slid onto one of the mismatched stools. She shrugged, admiring the way her big toe stuck out of a hole in her left sock. This toe had lost and regrown its nail three times and now had more ridges than the Appalachian Trail. It wasn’t a toenail—it was a formality.

“Fine. Marz needs a new drummer, so her sister’s filling in.”

“Which one?”

“Mom, which do you think? Gigi is eight.”

Marz had two younger sisters, Alcina (Cee, mostly), and Gioconda (Gigi, always).

“I dunno, I hear she plays a me. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...